The following article is written by Nicholas Seay, PhD student in the Department of History at Ohio State University interested in Central Asia’s cultural history. His current project looks at the social, cultural, and political history of cotton and its growers in Soviet Tajikistan. He serves as the host of New Books in Central Asian Studies on the New Books Network.

***

In step with counterparts across the globe, the countries of Central Asia have been forced to address the threat posed by Covid-19. They have approached the pandemic with mixed levels of sincerity and precaution. Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan have adopted strict lockdown measures in major cities, while Turkmenistan continues to maintain that it has no cases and Tajikistan downplays the severity of the pandemic. Despite the range of approaches, ordinary people anticipate economic consequences and disruptions in their daily lives.

Many have turned to social media to share hope and humor in a time of despair. Among the various videos, photos, and memes shared, one of the most popular is a clip from the black-and-white Soviet film Avicenna (Avitsenna) from 1956.

Featuring a number of Soviet Central Asian actors sporting turbans, tunics, and well-trimmed beards, this Russian-language biopic follows the titular figure of Abū ‘Alī Huseyn ibn ‘Abdallāh ibn Sīnā, commonly known as Ibn Sina or Avicenna. The film’s plot takes viewers back to 11th century Central Asia, following Ibn Sina as he traverses a politically dynamic Persianate world. In the clip, a pandemic is sweeping Central Asia and Ibn Sina can be seen giving medical advice as to how to survive the “Black Death”. Why would a Soviet film about an eleventh century philosopher have so much relevance now?

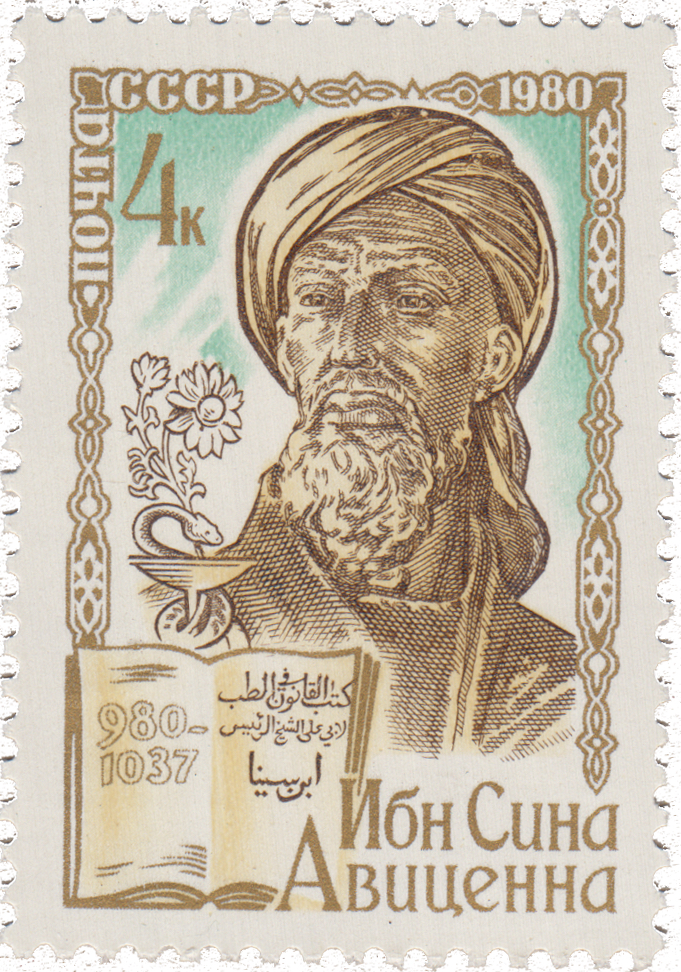

Ibn Sina was born in 980 in Afshana, a village near Bukhara in modern day Uzbekistan. His father served as governor under the Samanids, a Persian-speaking empire that reigned over an efflorescence of culture in Central Asian cities during the 9th and 10th century. Part of a larger cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing known as the Islamic Golden Age, late Samanid rule saw the emergence of classic literary figures like Rudaki and Ferdowsi, the latter being the author of the famous Shahnameh (Book of Kings). Ibn Sina’s family moved to Bukhara, where the young boy studied with a private tutor. In his youth, Ibn Sina showed great talent and, by the age of eighteen, gained a reputation for philosophical and medical knowledge. He lived in Bukhara during a period when the city was under threat from and eventually conquered by the Turkic Qarakhanid dynasty. Ibn Sina left Bukhara, first through Ghaznavid territory in Gorgan (now in contemporary northeastern Iran), then traveled west, spending longer periods in Isfahan and Hamadan, where he died in 1037.

As a central figure in the Islamic Golden Age, Ibn Sina is known for major contributions in fields including philosophy, logic, mathematics, physical sciences, medicine, biology, and literature. In the field of medicine, Ibn Sina built on the knowledge of Aristotle, the Graeco-Roman physician Galen, and important Islamic physicians like his Abu Bakr Muhammand Ibn Zakariyya al-Razi, another figure from the Samanid Empire. One specialist described his five-volume The Canon of Medicine (al-Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb) as a “godsend for later physicians” because it served as both an introductory textbook for newcomers to medicine and as a quick and relatively concise handbook for seasoned doctors.

Avicenna presented a reconceptualization of medicine as both practical and theoretical science. Whereas previous physicians thought of medicine in terms of tending to the patient’s ailments, Avicenna sought a theoretical basis for medicine by examining the causes of health and disease. The Canon was widely used throughout the period in both the realms of Islam and Christendom. The later was possible because Muslim communities in Italy and Spain introduced the texts to Europe after they were translated into Latin by the 12th century. Even as late as the 15th and 16th centuries, his work was included in the curriculum of medical schools in Europe. Other important works by Avicenna, such as The Book of Healing (Kitab al-Shifa), explored philosophy, astronomy, chemistry, earth science and mathematics.

Ibn Sina in the Soviet Union and Contemporary Central Asia

When the Bolsheviks came to power in in the early 20th century, they inherited an empire that had frequent contact with neighboring Muslim communities for centuries. Many of the Tsarist scholars engaged in Oriental Studies (the term used to refer to Central Asian and Middle Eastern Studies) found themselves working for the new Soviet government. Figures like Aleksandr Semenov, Vasilii Bartol’d, and Evgenii Bertel’s played an important role in Soviet scholarship on neighboring regions and impacted the formation of national identities and republic borders among the Muslim societies in Soviet Central Asia.

Oriental Studies became an important realm of prestige in the Soviet Union. Political figures such as the Secretary of the Communist Party of the Tajik SSR from 1946-1956 Bobojon Ghafurov doubled as Oriental scholars. After 1956, Ghafurov moved to Moscow, where he served as Director of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union, where he also played an important role in Moscow’s policy towards non-aligned countries of the former colonized world. The study of figures like Ibn Sina featured prominently in the work of such scholars, especially in the post-WWII period.

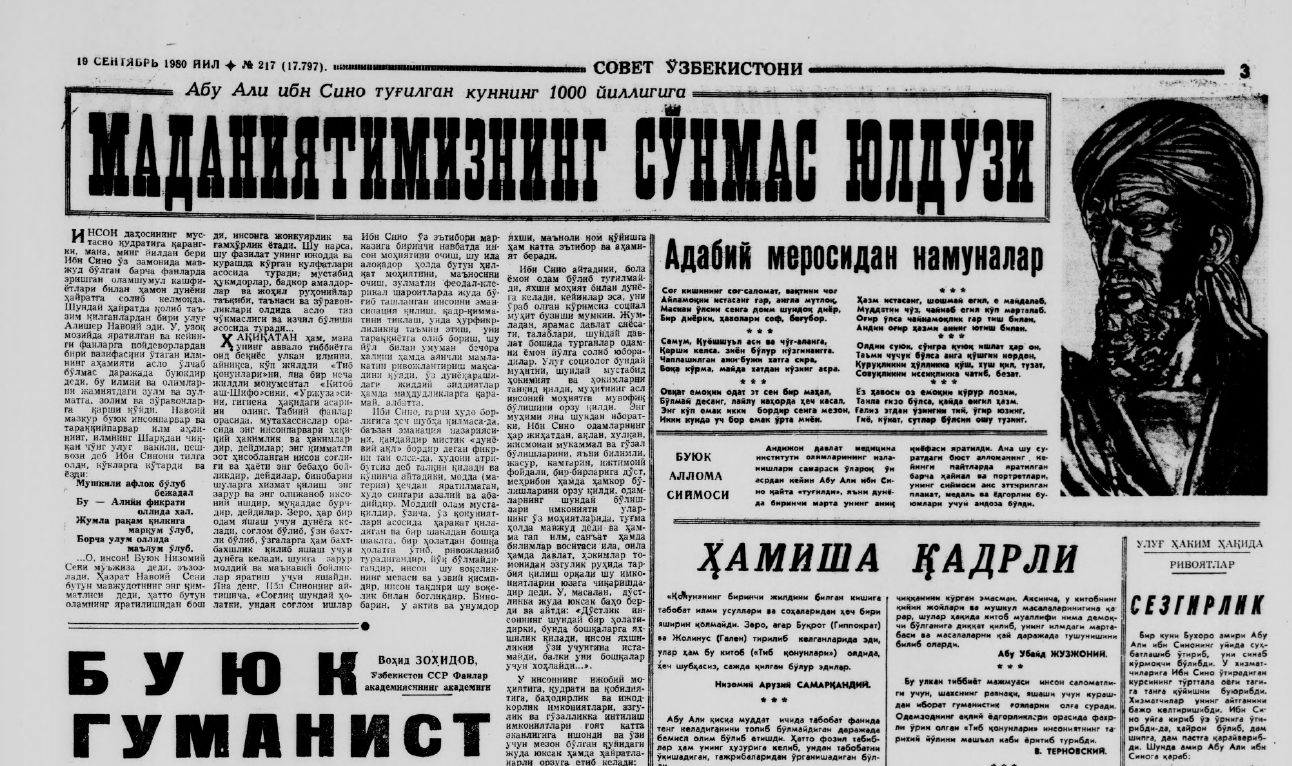

Yet Ibn Sina highlights some of the contradictions of Central Asian nation-building projects. Soviet republics promoted versions of their history in which they elevated historical figures to “national” heroes. A figure like Ibn Sina – who lived across Central Asia and Iran, and who worked mostly in Persian and Arabic – does not easily fit into the schemes of modern nations. Despite this, he was adopted by many nation-building projects in the region as a figure whose contributions were worth celebrating, especially for the former Uzbek and Tajik Soviet Socialist Republics. In 1980, for example, Moscow held a 1000-year jubilee celebrating the birth of the famous native-Bukharan, a fact celebrated in both of the republics’ main newspapers.

The 1956 film following Ibn Sina was a truly Soviet Central Asian production, the film was a collaboration between creative minds in the Soviet Republics of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Directed and released by Kamil Yarmatov, the film was produced by the Tashkent Film Studio in 1956 and its screenplay was co-written Viktor Vitkovich (a Russian screenwriter working and living in Uzbekistan) and Sotym Ulugzoda, a prominent writer in the Tajik Writer’s Union.

As was the case in the scholarly research and celebratory events that focused on the figure of Ibn Sina, the 1956 biopic emphasized the “progressive” nature of the hero and his work. In the Soviet Union, intellectuals and film producers could downplay the religious nature of historical figures like Ibn Sina and celebrate their “rational” nature, achieved by focusing attention on their scholarly contributions. Anti-religious attitudes in the Soviet Union had become part of official public life; the state and the Party had a history of open hostility towards Islam in Central Asia. This was most notable during the wildly unsuccesful unveiling campaigns of the late 1920s, which were devastating for Central Asian women who faced unprecedented levels of violence in the campaign’s wake.

In Soviet society more broadly, religion was largely driven underground; religious practices in Central Asia continued, but in less institutional settings. These anti-religious attitudes impacted the reconstruction of Ibn Sina as a historical actor. While the real Ibn Sina would have seen “religion” and “science” as inherently interrelated, the film producers instead rendered the forces of religion and scientific rational thought as incompatible.

English translation:

The clip begins as Ibn Sina’s listeners ask him about the probability of battling the “Black Death.” This is not the bubonic plague that affected Europe and Asia in the 14th century, but instead a reference to regular bouts of plague in Central Asia during the late-Samanid period, which led to scattered rebellions and the death (by plague) of various rulers. In response to the threat of pandemics, Ibn Sina makes the timeless call for people to stay home in isolation to avoid spreading the contagion. He also suggests the closure of public spaces, including bazaars and mosques. The scene ends on a rather anti-religious note, typical of the Soviet period. The camera zooms in on one of the listeners expressing concern that, if they close the mosques the “fanatics” will tear them apart. The film thus sets up a contrast between Ibn Sina, resembling a secular intellectual, and the “fanatic” believers, that resembles Soviet anti-religion propaganda in general.

In a time when Islamic identities have again become increasingly central to public life in Central Asia, it is interesting to revisit Soviet films like this one. While the film and the clip had been produced with a dose of anti-religious propaganda, its reemergence has provided an opportunity for individuals to openly discuss the film’s relevance to contemporary meanings of what it means to be Muslim. In comments on these videos, some viewers openly object to the propagandistic nature of this Soviet film. On one thread, for example, a commenter accused the clip of being blatant “Soviet Propaganda,” particularly because of how Communist ideology had influenced the interpretation of facts. Others suggested that the Soviet cinematographers relied on concrete facts, explaining that quarantine was widely used in the Islamic world.

Finally, and perhaps most productively, one commenter suggested that it was simply possible to “look beyond the Soviet interpretation” and think about the “fanatics” not in terms of their relation to the mosque, but instead think about “fanaticism” (here, meaning the non-rational, anti-science) as something divorced from religion. If in the Soviet Union, the rational and scientific nature of Ibn Sina’s thinking was cast as something in opposition to Islam, the film as it has resurfaced during Covid-19, has provided a platform for moving “beyond the Soviet interpretation” and framing a sort of modern Islam that is not “fanatic” but can go hand-in-hand with “rational” measures during a pandemic, including the closing of mosques.

Many found something positive in Ibn Sina’s message to stay calm, overcome fear, and avoid public spaces when possible. While the future of Covid-19 appears unclear and even frightening, for many this Soviet-era film offers some hope and a sense of control amidst the chaos. The memes, which have provided an internet afterlife to a Soviet film from the 1950s in the days of a pandemic, serve as a reminder of how culture is constantly re-interpreted and even affects the way we think about ourselves and our collective pasts.

1 comment

This advice from the famous Muslim philosopher and medic Abu Ali Ibn Sina’s (Avicenna) is as relevant for coronavirus today as it was for the Black Death in 11th century Central Asia. Perfectly captured in a 1956 Soviet Film. Thank you for the information in the research article..