The following post was written by Fuchsia Hart, a PhD Candidate in Oriental Studies based in the Khalili Research Centre for the Art and Material Culture of the Middle East at the University of Oxford. Her thesis explores the art and architecture of the major Shiʿi shrines of Iran and Iraq during the reign of the second Qajar ruler of Iran, Fath-ʿAli Shah (r. 1797-1834).

***

Religion, disease, and healing have a long and intricate history, and Twelver Shiʿi Islam is no exception to this. Its sacred sites are believed to provide healing – a small amount of the earth around the shrine of the third Imam, Husayn (d. 680 CE), in Karbala is believed to cure almost any ailment. Its liturgies contain prayers for healing – the fourth Imam, ʿAli al-Sajjad (d. 713 CE), included a much-recited prayer against sickness in his al-Sahifa al-Sajjadiyya (The Works of Sajjad). Its earliest leaders were also its doctors – the eighth Imam, Reza (d. 818 CE), is said to have compiled the medical work al-Risala al-Dhahabiyya (The Golden Treatise).

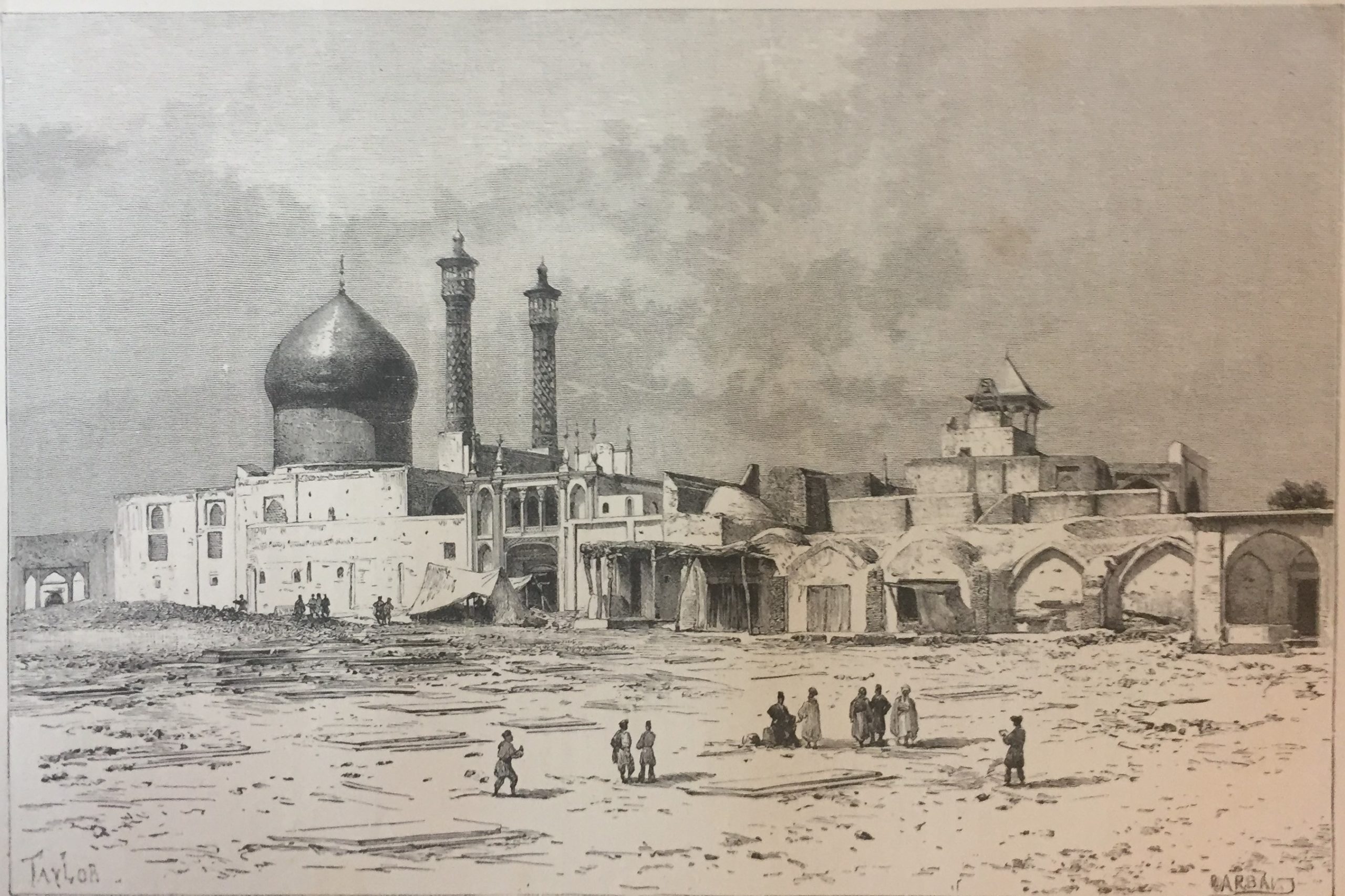

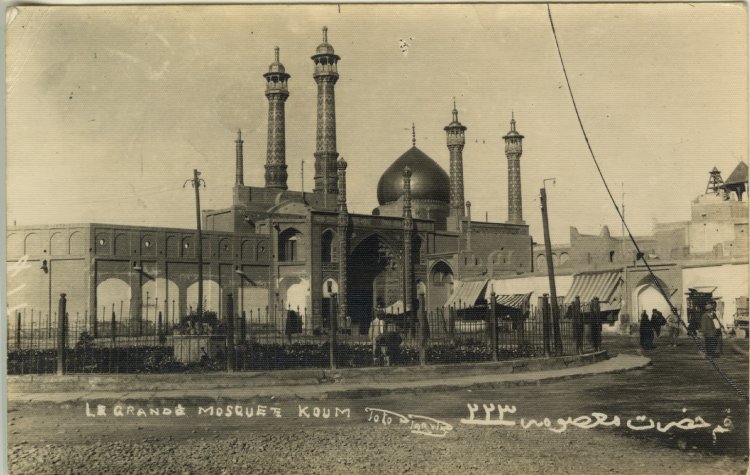

Healing at the Shiʿi shrines – as well as the possibility of their becoming vectors for the transmission of disease – came to the fore in recent months as COVID-19 spread across the Middle East. The virus first appeared in humans in China in December 2019, but Iran announced its first confirmed death from the coronavirus on February 19, 2020 – the first two cases having been reported from the shrine city of Qom, situated some 90 miles south of Tehran. Qom is home to the shrine of Fatima Maʿsuma, a major site of Shiʿi pilgrimage, now visited by millions of pilgrims annually. Initial fears focused on the possibility that the shrine, meant to be a place of healing for pilgrims who come from across Iran and the region, might have become a vector of transmission.

In the days which followed the initial appearance of coronavirus in Qom, the city would quickly be identified as the epicenter of the outbreak of the virus in Iran. It was feared that the dissemination of COVID-19 around the city, country, and region was facilitated by the huge number of daily pilgrims to the shrine for which the city is best known. While the situation in which Qom, Iran, and the rest of the world finds itself may feel frighteningly unprecedented at times, Qom is no stranger to disease or epidemics. For centuries it has attracted pilgrims from around the globe and its seminaries host students from many different countries. In the time of pandemic, however, pilgrims, students, and the shrine to which they so faithfully turn can also act as disseminators of disease.

The shrine at Qom is devoted to Sayyida Fatima Maʿsuma, the daughter of the seventh Shiʿi Imam, Musa al-Kazim, and the sister of the eighth, ʿAli al-Reza. Devotees believe that Fatima died in Qom around 816, while journeying to find her brother, who had left their home in Medina for the court of the ʿAbbasid caliph al-Mamun after he named Imam Reza as his heir. Fatima and her brother were destined never to be reunited, however, as she would die at Qom, and Imam Reza would die and be buried in the place now known simply as Mashhad (‘place of martyrdom’).

The spot where Fatima was buried was initially marked by little more than a structure of woven reeds. However, from shortly after her death, it began to garner enough attention and accrued sufficient wealth to become the grand complex it is today. It now incorporates the tomb itself, encircled by the burial sites of many of her devotees, as well as mosques, and madrasas. Hundreds, if not thousands, come to Fatima’s threshold on a daily basis to request her prayers and intercession. They come, as pilgrims have done for over a thousand years, to visit her tomb, under its now iconic golden dome, second in importance in Iran only to that soaring over her brother’s tomb in Mashhad.

The major Shiʿi shrines have long had a close association with both bodily and spiritual healing. There are even records of miracles taking place at the shrine of Fatima Maʿsuma. These famously include the healing of a lame man, reported in the Anwar al-Mushaʿshaʿin, a history of Qom. Following his prayers for intercession, Fatima is said to have appeared to Mirza Asadullah, rubbing the corner of her scarf on his diseased foot and curing him. Not all pilgrims will experience miracles, but they may visit the shrines of the Imams and their descendants to seek intercession for good health for sick loved ones.

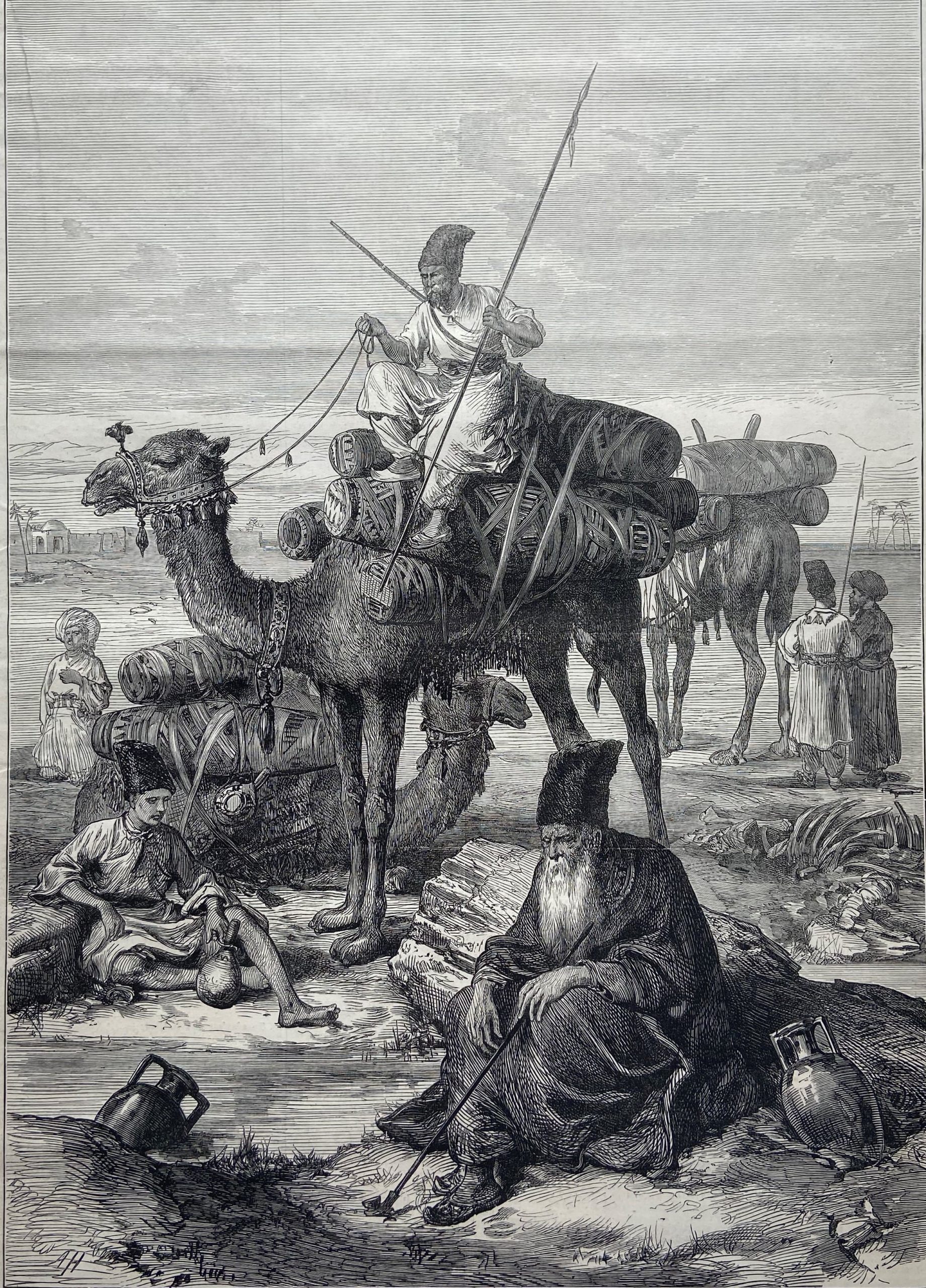

In the 19th century – the period which will be our main focus here – the caravans which facilitated pilgrimage to the shrine would have acted as carriers of disease, therefore simultaneously facilitating the outbreak of epidemics. While the advent of steam- and engine-powered travel accelerated the speed of the spread of disease, caravans formed of people on foot and beasts of burden would still have transported sickness, as well as pilgrims and goods.

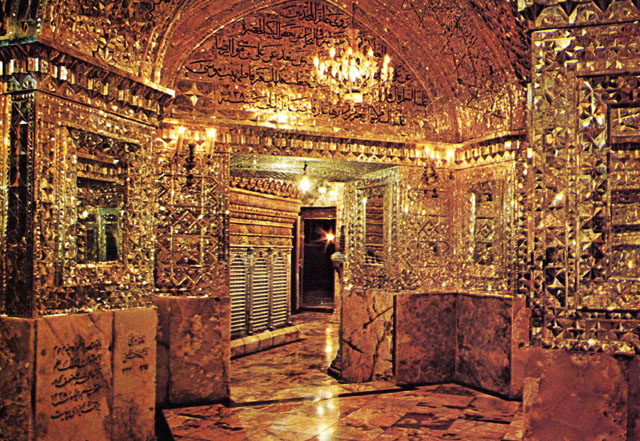

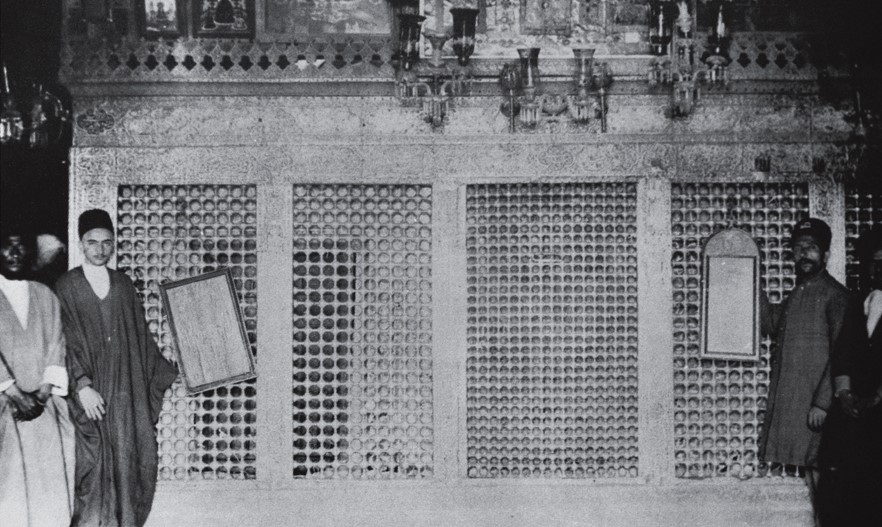

At the end of the journey, when the pilgrim arrives at the shrine, there are a number of prayers and ritual acts to perform. From the earliest days of pilgrimage to the shrine of Fatima, as reported in texts such as Ibn Qulawayh’s tenth century text on pilgrimage, Kamil al-Ziyarat (The Complete Pilgrimage), pilgrims have been encouraged to touch and kiss the tomb. Pilgrims still often rest their heads against the tomb as they pray, touching the grill to obtain its blessing (barakat) and show reverence. In the 19th century, often hot, dirty, and tired from a long journey by foot and donkey, pilgrims would have pressed eagerly into the central tomb chamber, the culmination of their pilgrimage, and the sheer presence of so many in a confined space would have likely hastened the spread of disease.

Some pilgrims may even have begun their journey knowingly ill, seeking a cure, or at least hoping to end their days in this world in the sacred environs of Fatima’s tomb. During the 1918-19 outbreak of influenza in Iran, which hit the city of Shiraz particularly hard, some of the sick are reported to have, in a last act of desperation, dragged themselves into the safety of the nearest mosque. This was an attempt to secure salvation, or at least a humane burial. Some would also fall ill on the way, as was the case for one pilgrim travelling to Mashhad alongside the East India Company’s Arthur Connolly in 1829. Connolly reported that some of his fellow travelers wanted to leave the man behind, but others vowed to help him complete his pilgrimage. The sight of the sick man’s face when he saw the gleaming golden dome over Imam Reza’s tomb made a strong impression on Conolly. The pilgrim, having reached his spiritual goal, would die on the evening of his arrival in the holy city.

Over the centuries, many have wished to be buried in the vicinity of these holy sites, again to benefit from the barakat emanating from the sacred remains into the earth of the city surrounding them. In this way, while the primary original function of the shrine at Qom was to mark the site of Fatima’s burial, and to facilitate visitation to her graveside, the site would go on to become the burial site for many others. From shahs to shaykhs to ordinary, although mostly affluent, people, secondary burial sites of others accrued around Fatima’s tomb in the hope of benefitting from the blessings emitted by the holy figure. Notably, five rulers of the Safavid dynasty and two from the Qajar dynasty are buried in lavish tomb chambers, appended to the buildings immediately surrounding the central tomb chamber. Fath-ʿAli Shah’s (r.1797-1834 CE) tomb chamber, prepared for him in advance of his death in 1834, was encrusted with baroque carved plaster work around his central cenotaph, topped by a hardstone lid carved with his iconic portrait. However, not all burials were so grand, let alone so neat, and the preparations, methods, and apparatus for burying others could be haphazard.

We have evidence, particularly from the 19th century, that the arrival of bodies was a way in which disease entered the town. In order to follow the Islamic practice of burial shortly after death, the dead would often be buried close to home, only to be exhumed later in varying states of decay to be transported to their final resting place. Reburial during holy days was favoured and there would be an increase in corpse traffic around significant festivals. The delay in the final burial allowed less-wealthy families time to gather necessary funds for transportation of the body and formal burial. Those with greater economic means could take or send the remains of their family members further afield to the even more sacred soil of the Iraqi shrine cities, across the border within Ottoman lands. As Sabri Ateş has shown, in the second half of the 19th century, this practice was recognised as a possible source for the movement of disease and requirements were put on the movement of corpses. Bodies were required to be embalmed, moved in properly sealed biers, and only transported during the cooler, winter months, to slow the process of decay and reduce the volume of potentially harmful miasmatic emissions.

Isabella Bishop, who travelled through Iran in the 1890s, visiting Qom, provides us with a vivid picture of this practice. She writes that thousands were brought yearly to be buried in the ‘sacred soil’. The ‘corpses travel… on mules, four being lashed on one animal occasionally, some fresh, some decomposing, others only bags of exhumed bones’. She describes the practice as a great source of income for Qom, with the price varying ‘on proximity to the dust of Fatima from six krans to one hundred tumans’. Before the advent of germ theory, it was believed that the inhalation of the noxious smells emanating from the corpses was the main way of contracting disease. While the theory of miasma has now been shown to be unscientific, unsatisfactory burial practices of cholera victims may still have accelerated the spread of the bacteria. James Baillie Fraser, a Scottish witness to Iran’s and, indeed, the world’s first outbreak of cholera, in 1821, lamented how little was generally known about the spread of the disease – he would see people continually involved in assisting the sick remaining free of the disease, but also saw cases where ‘whole parties concerned in burying… the body of one of its victims have themselves been carried off’.

We now know that water can often facilitate the spread of disease, and waterways associated with shrines would be no exception. Mrs Bishop points out that a waterway in Qom, ‘the Ab-i-Khonsar, which supplies the drinking water, percolates through dead men’s bones and all uncleanness’. The river running adjacent to the shrine would have served a gamut of ritual and mundane purposes, for both the living and the dead. The living would drink the water, use it for washing themselves and their clothes, make their ablutions in it, as well as cleansing their dead in it. Such a range of uses for the river water was generally sanctioned by the status of running water as pure (tahir, as opposed to najis, impure). During the 1904 cholera outbreak, the bodies of those who had recently succumbed to the disease were washed in the river, which would then be used for domestic purposes, almost certainly contributing to the spread of the water-borne bacteria. Qom alone would lose 1,000 of its residents to this one outbreak.

Thankfully, over the course of the 19th century, Iran developed a health care system which grew to be able to contend with outbreaks of cholera and plague. As Amir Afkhami has demonstrated, by the 20th century, the country had what can be described as a fully secularized and modernized healthcare system. Disease came to be understood and responded to in terms of germ theory, rather than through the lens of divine wrath. In this regard, it’s interesting to note that many of the first modern hospitals in Iran were attached to shrines, and the concept of the shrine as a healing space was extended to include modern medicine.

Today, shrines across Iran remain shut, having been ordered to close by the government in the wake of the rise of COVID-19 cases across the country. In late February, as the contagion spread through Qom, a concerted programme of disinfection began within the shrine, but fears persisted about the role the space might be playing in transmission of the virus.

Calls for the shrine’s closure were initially met with suspicion from some, arguing that such a time was in fact when such a site was most needed. Videos even circulated of individuals provocatively licking the tomb – an act outside the usual ritual practices associated with pilgrimage – and urging viewers not to be afraid of visiting Fatima. Global uproar followed the release of these images and those shown were quickly arrested.

A contentious public debate followed about whether the shrine was a place of healing or contagion. Within a few weeks, the matter was settled as the state imposed full closures on the shrines- though not before a few protests, including one in which a crowd broke the doors and forced their way in.

Behind the closed doors, some shrines are now being put to a new sort of use, such as at the Shah-Cheragh shrine in Shiraz, in which surgical masks are being produced under the mesmerizingly intricate mirror-work ceilings, echoing the longer history of these shrines as sites for mitigating the effects of disease.

Iran’s current situation and the effect which the coronavirus pandemic has had on the country feels like the latest in an unrelenting series of disasters, set within the longer history of sanctions against the country which have undermined its healthcare capacity. Thankfully, the rate of new infections and deaths from coronavirus in Iran has now slowed, and some of the more stringent lockdown measures imposed back in February have been lifted. The shrines, however, are to stay closed for some while longer.

In the meantime, devotees can still approach Fatima Maʿsuma through various online portals which simulate pilgrimage, and there has even been a religious radio show broadcast from inside the shrine. A few pilgrims can still occasionally be seen, outside the closed gates around the perimeter of the shrine, observing the now customary social distance, coming to pay their respects from afar, and perhaps gaining some comfort and healing from the shrine at this difficult time.

Further reading:

Sabri Ateş, ‘Bones of Contention: Corpse Traffic and Ottoman-Iranian Rivalry in Nineteenth-Century Iraq’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2010

Amir Afkhami, A Modern Contagion: Imperialism and Public Health in Iran’s Age of Cholera.

Bijan Saadat, The Holy Shrine of Imam Zadeh Fatima Maʾsuma, Qum.

Archnet, Astanah-i Hazrat-i Ma’sumah

2 comments

thank you for this fascinating piece if Iranian history!

Amazing piece! Feel like I’ve traveled through the last century of epidemics in Iran. Will read more about the topic, thanks so much