The following article is written by Chihab El Khachab, a Junior Research Fellow in Anthropology in Christ Church, University of Oxford. His research interests are at the intersection of cinema, media, and popular culture, primarily in Egypt and Afghanistan.

Afghanistan’s national film institute Afghan Film has uploaded many of the films mentioned in this article to the “Treasures of Afghan Film” section of the online streaming platform Darya, where they can be viewed free of charge.

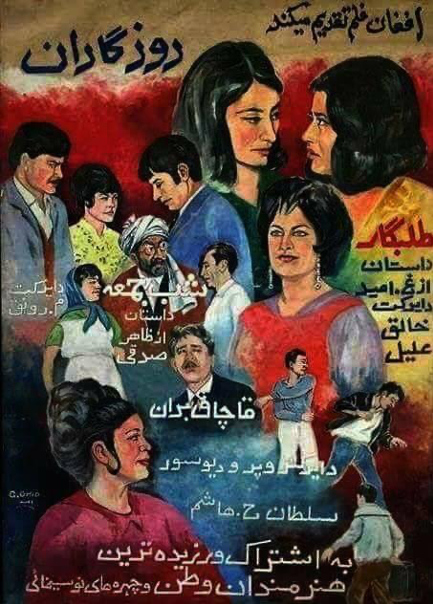

On August 27th, 1970, The Kabul Times, a governmental English-language newspaper, published a front-page story titled “First Afghan Film Feature Premiered in Kabul Nandarey”. The film in question, called Rozgārān (The Times), was actually one showing in which three films with separate casts and crews were projected. The first film, Talabgār (The Suitor), is a 39-minute-long drama about a conniving young man who poses as a respectable suitor to gain his love interest’s hand in marriage, only for his subterfuge to be uncovered by the family. The second film, Shab-e Jom‘a (Friday Night), is a 31-minute-long vaudeville about an arranged dinner between a suitor and the bride-to-be’s family. The third film, Qāchāqbarān (The Smugglers), is a 53-minute-long action drama about a gang of smugglers who are planning a big operation until the heroic national police foils their plan.

While different in style and content, the films composing Rozgārān were the first features produced by Afghan Film, the institution charged with film production and distribution within Afghanistan’s Ministry of Information and Culture. Hailed in their own time as an auspicious beginning to Afghan cinema, these films were not, in fact, the first ones made in Afghanistan. Yet they signaled a renewal of the project to create a national film industry based in Kabul. Afghan Film opened its doors in 1968, after a long-term collaboration with USAID came to fruition. The collaboration, whose idea began in 1961, was primarily meant to build a small film laboratory in Kabul to produce newsreels and short documentaries. The overwhelming majority of these films were in Persian (Dari), with a select few in Pashto – a pattern that continues to this day in fiction and nonfiction cinema alike.

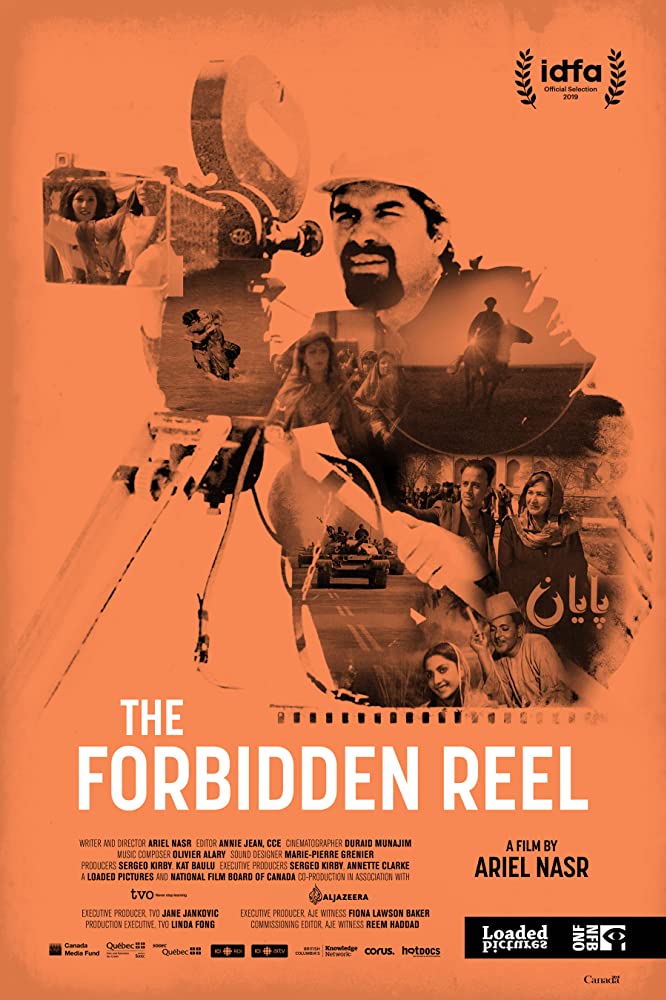

After a few co-productions with local companies in the 1970s, including the historical epic Rabe‘a Balkhi (1974) and the psychological drama Mojassama-hā mikhandand (The Statues are Laughing, 1976), Afghan Film saw a surge in funding in the wake of the 1978 Saur coup. Seeing cinema as an important tool to educate the illiterate masses, the communist government encouraged the production of widely-diffused nationalist films such as Sabūr-e Sarbāz (Soldier Saboor, 1985) and Hamāsa-ye Ishq (Love Epic, 1989), in addition to the many unfinished productions explored in Mariam Ghani’s What We Left Unfinished (2019). After the fall of the communist regime, the civil war and the subsequent Taliban regime in the 1990s hampered film production. Afghanistan’s film heritage was rescued in extremis by the archivists working in Afghan Film in the 2000s, as explored in Pietra Brettkelly’s A Flickering Truth (2015) and Ariel Nasr’s The Forbidden Reel (2019). Until 2001, when Kabul became the site of internationally-funded film productions as well as low-cost made-to-video movies, there had been no more than forty-five Afghan fiction films made according to the director and ex-head of Afghan Film, Siddiq Barmak.

While Afghanistan never had a large-scale film industry, state administrators and Kabul’s educated public envisioned the idea of creating an Afghan national cinema on numerous occasions throughout the 20th century. This idea did not begin with Rozgārān in 1970. It had been integral to Kabul-based nationalist developmental discourse emerging since Afghanistan’s independence in 1919. In this context, cinema was one artistic initiative among others designed to create a national culture under central government guidance.

Reconstructing the beginnings of Afghan cinema shows the historical depth behind this developmental discourse. This historical attention decentres narratives about modern Afghanistan as a war-torn blank slate, upon which an ongoing “reconstruction” has been superimposed since the 2001 United States-led occupation. Such narratives erase local and national histories, whose interpretation exceeds an American-centric framework. Recovering these histories shows the persistent connection between Afghan cultural production and centralized attempts at building a modern nation-state in Afghanistan over the last century.

The story of early filmmaking in Afghanistan is, in many ways, the story of its rulers. King Amanullah Khan, who had secured Afghanistan’s recognition as an independent nation in 1919, hired a personal film crew to record his long international trip in 1927-1928. Although he was deposed in 1929, the surviving footage is likely the earliest trace of Afghan audiovisual production. Thirty years later, in 1959, the Independent Press Directorate (which would become Ministry of the Press in 1964 and Ministry of Information and Culture in 1966) created a film production unit under filmmaker Akbar Shalizi’s supervision. The unit’s immediate function was to document the travels and political achievements of King Zahir Shah, who had been in power since King Nadir Shah’s assassination in 1933 and remained on the throne until the 1973 republican coup of his Prime Minister, Daoud Khan.

While newsreels have historically constituted the bulk of films made in Afghanistan, fiction films were far and few until Rozgārān. In an extended interview with the weekly entertainment magazine Zhwandoon in 1970, Sultan Hamid Hashem, then the head of Afghan Film, explained to the reporter how difficult it was to make Rozgārān given the inadequacy of the existing infrastructure and lack of trained technicians. Hashem added that while numerous documentaries had been produced in the country, “people didn’t consider documentaries as ‘films’”. He was nevertheless proud that this was the first film whose entire process (including post production) was conducted in Afghanistan, and he was hoping that it would be a sign of things to come – with additional technical and financial help from the Ministry of Information and Culture.

Yet Rozgārān was not the first feature shot in Afghanistan. Some six years earlier, on October 4th, 1964, The Kabul Times published a story titled “First Afghan Movie Production: Like an Eagle”. This film was Mānand-e ‘Oqāb (Like an Eagle), a 79-minute-long tale with an experimental flavour. The film was a collaboration between the filmmaking unit at the Ministry of the Press (the kernel of what would later become Afghan Film at the Ministry of Information and Culture) and the Fine Arts Institute whose head, Fayz Mohammad Kheirzadah, directed the film. The story follows Shahla, a young girl from Paghman on the outskirts of Kabul, who is itching to see the national independence celebrations (jashn-e esteqlāl) in the capital.

After an initial dialogue with her doll where she explains her intentions, Shahla walks down from the mountain onto the asphalted road leading to Kabul. She spends a whole day there to watch the celebrations, until she comes back to her village “having become a grown woman,” as her mother tells her in the closing scene. The film mixes actual newsreel footage from the 1963 independence celebrations with inserts on Shahla walking around Kabul and watching concerts by prominent Afghan musicians, including Ustad Sarahang, Ustad Jalil Zaland, and Ustad Hamahang. The newsreels showcase military parades, folkloric dances, and national sporting displays, while capturing the reaction of the watchful monarch Zahir Shah. His predominant presence in the newsreel footage contrasts with the cheeky glances of Shahla in the middle of the fictional reel, acting as a counterpoint to the king’s gaze onto the proceedings.

Unlike Rozgārān, which had moviegoers crowding up at ticket counters two weeks after its initial release in 1970, Mānand-e ‘Oqāb was not a popular success. The movie critic writing in The Kabul Times complained that “there are a number of episodes and scenes which are confusing and in fact uncomprehensible (sic).” The contemplative scenes and the jagged back-and-forth editing between fiction and documentary may have jarred this viewer, who would have been used to watching the American, Indian, Russian, and Iranian productions on offer in Kabul’s theatres in the 1960s. Yet this film remains an intriguing artistic take on the Afghan state’s developmental discourse, as seen through the eyes of a young girl.

Mānand-e ‘Oqāb may have been the first film shot mostly in Afghanistan by an Afghan crew, but it is not the first fiction film shot in Kabul. In his Zhwandoon interview, Sultan Hamid Hashem mentioned that an earlier film had been “partly made in [British] India.” In its own time, however, this film was conceived as a first in Afghanistan. Writing to the foremost Persian-language governmental daily Anis on September 9th, 1946, a certain Mohammad Rahim Khan Sheyda called it “Our First Film”. The letter stated that the film was “short but sweet,” and it expressed amazement at how quickly a Persian film was made given the absence of basic financial and technical means in Afghanistan. This letter came at the tail end of a month of critiques and conversations concerning the film on Anis’ pages.

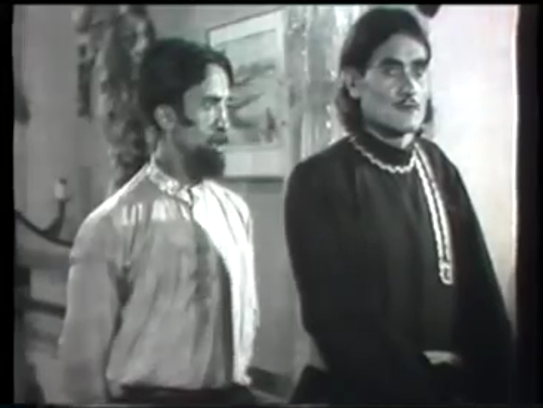

The film in question was Ishq wa Dusti (Love and Friendship), a 43-minute-long musical drama written by Rashid Latifi, a pioneer of Afghan theatre, but mostly shot at the noteworthy Shorey Studio in Lahore and directed by Harold Lewis, an actor who was known to early South Asian cinema audiences as “Majnu”. Ishq wa Dusti is an allegorical tale about a poet and an aging captain vying for the hand of Mariam. The captain, who knows nothing of the poet’s love, asks him to request Mariam’s hand in marriage. The poet is torn between love and friendship, until the film finds a happy resolution. This story unfolds in around half of the movie’s scenes, whereas the other half is made of musical sequences whose style bears the imprint of Indian song-and-dance sequences, yet with Persian lyrics.

Ishq wa Dusti seems to have been a success after its initial release. A reporter from Anis, summarizing the proceedings at the 1946 national independence celebrations where the film premiered, wrote that “people in tight crowds hurried to watch it.” Mariam Ghani has noted the intimate link between cinema and celebrations of national independence in Mānand-e ‘Oqāb, but the link seems to have been deeper historically, insofar as both Ishq wa Dusti and Rozgārān were premiered on the first day of national independence as well. Any new “beginning” to Afghan cinema, it seems, was integrated into the spectacle surrounding the country’s independence celebrations. Projecting Afghan film “firsts” on these occasions was yet another marker of authenticity and modernity on the nation’s stage, next to the military parades, the folkloric dances, and the sporting events.

Ishq wa Dusti did not stay very long in theatres. A disappointed viewer, Abdul Ghafur Qayyumi, recounts in a letter to Anis that he returned over and over again to the theatre without finding the film a mere month after its premiere. Qayyumi simply referred to it as “the Persian film,” as did many readers who exchanged opinions on Anis’ pages. While some Iranian films would show in Kabul by the 1960s and 1970s, it seems that this was not the case in 1946. What marked the film’s uniqueness to Anis’ audience, in contrast to the usual American and Indian films, was its language and its national significance. The “Persian film” discussed in the newspaper was inextricably an Afghan film, which Anis’ readers had hoped to be the first in a nascent national film industry.

These hopes never came to fruition. Eighteen years would elapse before the audience of Ishq wa Dusti would see another Afghan feature film. Between 1946 and 1970, there were three “firsts” in Afghan cinema, three starts and stops to a fiction filmmaking world that never became an industry comparable to Bombay, Lahore, or Tehran. The technical and financial obstacles were too great, and the kernel of filmmakers and viewers in Kabul too small to develop on a comparable scale to these neighbouring cities. Yet each time a new beginning to Afghan cinema was announced, one could discern the outlines of a nationalist developmental vision in which an emerging film industry signalled the way to modernity. In some cases, as in Mānand-e ‘Oqāb, the intimate link between cinema and modernity was displayed into the very fabric of the film.

The different “beginnings” of Afghan cinema did not acknowledge one another in a strong manner, as though they were starting over again each time. Was it historical amnesia? Or a constant redefinition of what constitutes a “true” Afghan film in different eras? Or a willful effort to create a blank slate for the anticipated rebirth of a new Afghan cinema? Whatever the case may be, the ever-renewed desire to create a national Afghan cinema shows how integral filmmaking has been to Afghanistan’s nation-building ambitions, even when it remained an unfulfilled project.

1 comment

”Like an Eagle”, a very interesting and often beautiful film in spite of the partly destroyed soundtape. Exiting to see it now – these days!