The following is a guest post by Amanda Caterina Leong, a Ph.D Candidate in Middle Eastern Studies at the University of California, Merced’s Interdisciplinary Humanities Program. Her research looks at the ways early modern women from Safavid and Mughal Empires were central to defining notions of ethics, power and empire-building that shaped the early modern Persianate world.

“Throughout the year in Persia, and particularly in Tehran, several fatal, infectious diseases rage because of unhygienic conditions. The streets are all filthy – in winter covered in mud and sludge, and in the summer dusty and dirt-encrusted. The watercourses are open and the filth from the houses is washed away into them. This water circulates through the town and people drink it and fall prey to all manner of maladies. […] Despite the fact that individuals who form corporations and take money from the people for public works- such as Haji Malek and other companies- give nothing back to the people but loss and regret […]. We seek progress and material acquisitions through unlawful channels, and that is why we never succeed or attain our goal.”

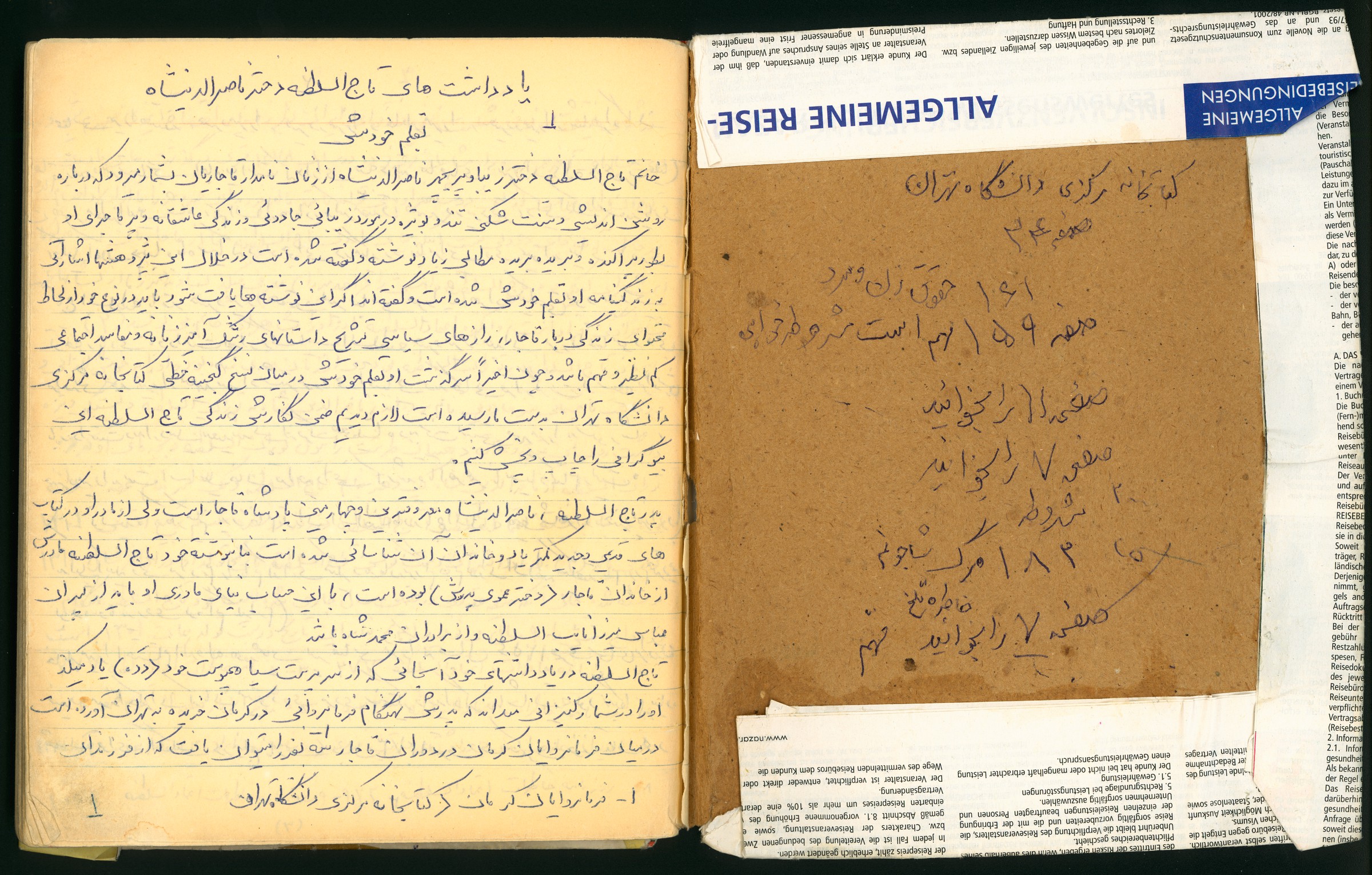

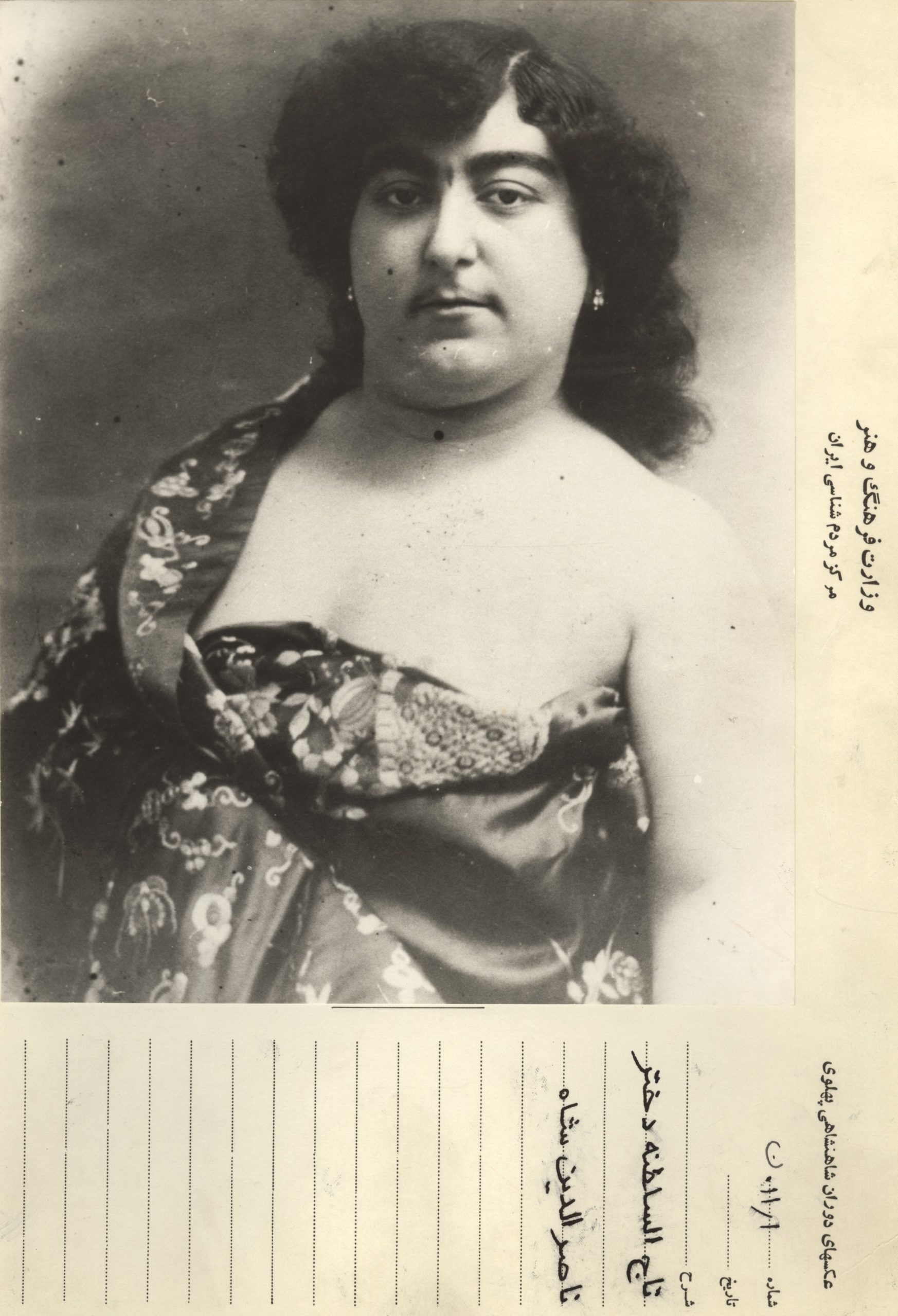

The above was written by Iranian Princess Taj al-Saltana in her memoirs, which were translated and published as Crowning Anguish: Memoirs of a Persian Princess from the Harem to Modernity 1884-1936. It is one of the only female-authored memoirs written during the Qajar period of Iran.

Taj al-Saltana, apart from being the daughter of Naser al-Din Shah, was a prominent intellectual and pioneering activist who fought for constitutionalism, freedom, and women’s rights in Iran. She wrote these words as she watched a cholera pandemic devastate Iran, one of many in the late nineteenth century.

Numerous cholera outbreaks, spread through war, trade, bad living conditions, and poor sanitation infrastructure, devastated turn of the century Iran and much of the world, providing a basis for Taj al-Saltana to argue against the wider ills of society that she believed the mishandling of these epidemics exposed.

In her memoir, Taj al-Saltana criticizes the failure of Iran’s Qajar government to control cholera, arguing it is due to poor governance, indicting patriarchy and corruption for the malaises facing the country.

Despite having been written more than a hundred years ago looking specifically at the cholera epidemic in Iran, Taj al-Saltana’s memoir has found new relevance in the age of COVID-19 and the failures of governance it has exposed worldwide.

In her memoir, Taj al-Saltana argues that the cholera epidemic in Iran is a punishment by “divine wrath.”

But her view is not fatalistic; she argues that God’s wrath is due to the Qajar government’s failure to follow the “Circle of Justice,” a Persian concept of rule which mandated that rulers legitimized by God are expected to rule with justice by caring for the welfare of its subjects.

Taj al-Saltana invokes God’s wrath to blame the government for its failure to maintain good hygiene in cities and to combat “contamination”:

“Though this epidemic was a sign of divine wrath and chastisement, we can still say that it was engendered by inattention to hygiene and the contamination of the water. Every government’s first duty is to see the cleanliness of the streets and the water, as well as the tranquility of the people.”

By invoking God’s wrath, Taj al-Saltana is able to use religion to mobilize her very scientific and intellectual argument about hygiene. She does not only reprimand the government for their failure to prevent the epidemic.

She further goes on to argues that “hygiene,” specifically a return to “cleanliness of the streets and water” and “tranquility of the people,” can only be attained by acknowledging the humanity of Iranian women like herself and allowing them to be active in public life, a cause for which Taj al-Saltana was a passionate advocate:

“If women in this country were as free as in other countries, enjoyed comparable rights, could enter the realm of government and politics, and could advance their lives […] I would choose a legitimate way and a determined plan for my advancement.”

In the following passage, Taj al-Saltana states what she would do if she were the ruler of Iran. She shows her female and even male readers how women like herself could be better rulers capable of restoring justice to Iranian people in the form of social and economic progress.

Crowning Anguish becomes a “mirror for princesses” that educates female readers on the possibility of being an ideal female ruler by showing what women can and should do for Iran:

“I would adhere to a conservative position, not for my personal good but for the commonwealth. I would make every effort to promote trade within Persia. I would build factories, not like the Rabi’ov soap-making plant, but ones that will make us independent of foreign trade. I would tap mines, which God has liberally bestowed on Persia. I would seize the rights to the Bakhtiyari oil fields which generate tremendous annual profits, not leave them to the British. I would find the means to facilitate agriculture and provide its necessities. I would build the Mazandaran highway and regulate the transportation of essential commodities. As they do in California, I would hand over barren land to the people and ask them to make it productive. I would dig numerous irrigation wells and create artificial forests. I would divert the Karaj River towards the city and thereby rescue the people from the misery of filthy water.”

With her plans for transforming Iran, Taj al-Saltana challenges the dominant notion held during that period of women as “uninformed” and not capable of “finding a lawful way toward advancement,” especially when “the man of [their] land have found no way to progress.”

Although Taj al-Saltana never managed to become Iran’s ruler, many of the plans she proposes in her memoir would be successfully carried out in the 20th century. And following her, many more Iranian women became active in public life, taking part in the Constitutional Revolution and women’s activism throughout the 20th century.

Her memoir has special meaning today, as another pandemic raging around the world highlights the failures of existing political systems and the urgent need for reform.

The fact that hers is a woman’s voice is especially important; today, Iranian women make up 90% of frontline nurses and face the highest risk of getting infected, while recent campaigns like the #metoo movement taking over Iranian social media and new book covers designed to fight against the erasure of women from textbooks highlight the active role of Iranian women on the frontlines of fighting for change and demanding inclusion.

Taj al-Saltana at one time mentions that she knows her struggle is a long one, urging her readers to remember that “one deception must not make us withdraw from the arena” but that instead, they should keep fighting.

A century later, her words and resistance against the failures of patriarchal governments to stop pandemics ring truer than ever, and urges us to come up with better strategies of reform to challenge hegemonic socio-political structures.

References

Tāj al-Salṭanah, and Abbas. Amanat. Crowning Anguish : Memoirs of a Persian Princess from the Harem to Modernity, 1884-1914 . 1st ed., Mage Publishers, 1993.

1 comment

It’s very interesting reading the transcript of the memoir, it is not written in first person narrative. Is this the case throughout the entire memoir or is the page in the picture some sort of intro written by the transcriber?