This is the first of a three-part series on arts associated with protection and healing in Islam by Professor Christiane Gruber. Throughout the history of Islamic societies, ordinary objects have become vessels for connecting with the divine and seeking protection in trying circumstances. Just as in the present, when people around the world seek comfort in homemade remedies to alleviate their fear of the pandemic, historically during times of plague, amulets, blessed water, and even talismanic shirts have been drawn on for safety and healing.

Christiane Gruber is Professor and Chair in the History of Art Department at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; President-Elect of the Historians of Islamic Art Association; and Founding Director of Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online. Her fields of interest include Islamic ascension texts and images, depictions of the Prophet Muhammad, book arts, amulets and talismans, codicology, paleography, architecture, and visual and material culture from the medieval period to today. Her latest publications are her third monograph The Praiseworthy One: The Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Texts and Images (2019) and her edited volume The Image Debate: Figural Representation in Islam and Across the World (2019).

***

The COVID-19 outbreak is proving a test of our physical and emotional endurance as well as our trust in science. However, such faith is not just predicated on medical advances and interventions but also intersects with religious worldviews and creative practices across the globe.

As in many other faith traditions, pious and artistic responses to natural disasters in Islam stretch back through the centuries, and they are creatively deployed and updated over time. Whether in the past or today, drought, famine, floods, fires, earthquakes, and epidemics have spurred practices and products that were—and in some cases, continue to be—thought to protect individuals from both visible and invisible harm. While earlier Orientalist scholarship categorized such beliefs as “superstitious,” in recent years academics have stressed the importance of the occult arts—at both the elite and popular levels—along with their relationship to scientific knowledge production. Paying attention to the arts of protection and healing thus can spotlight the rich lived experiences of Muslim devotees, thus foregoing a legalistic-dogmatic approach to Islam that might overlook such traditions or even castigate them as non-normative, “folklorish,” or even “heretical.”

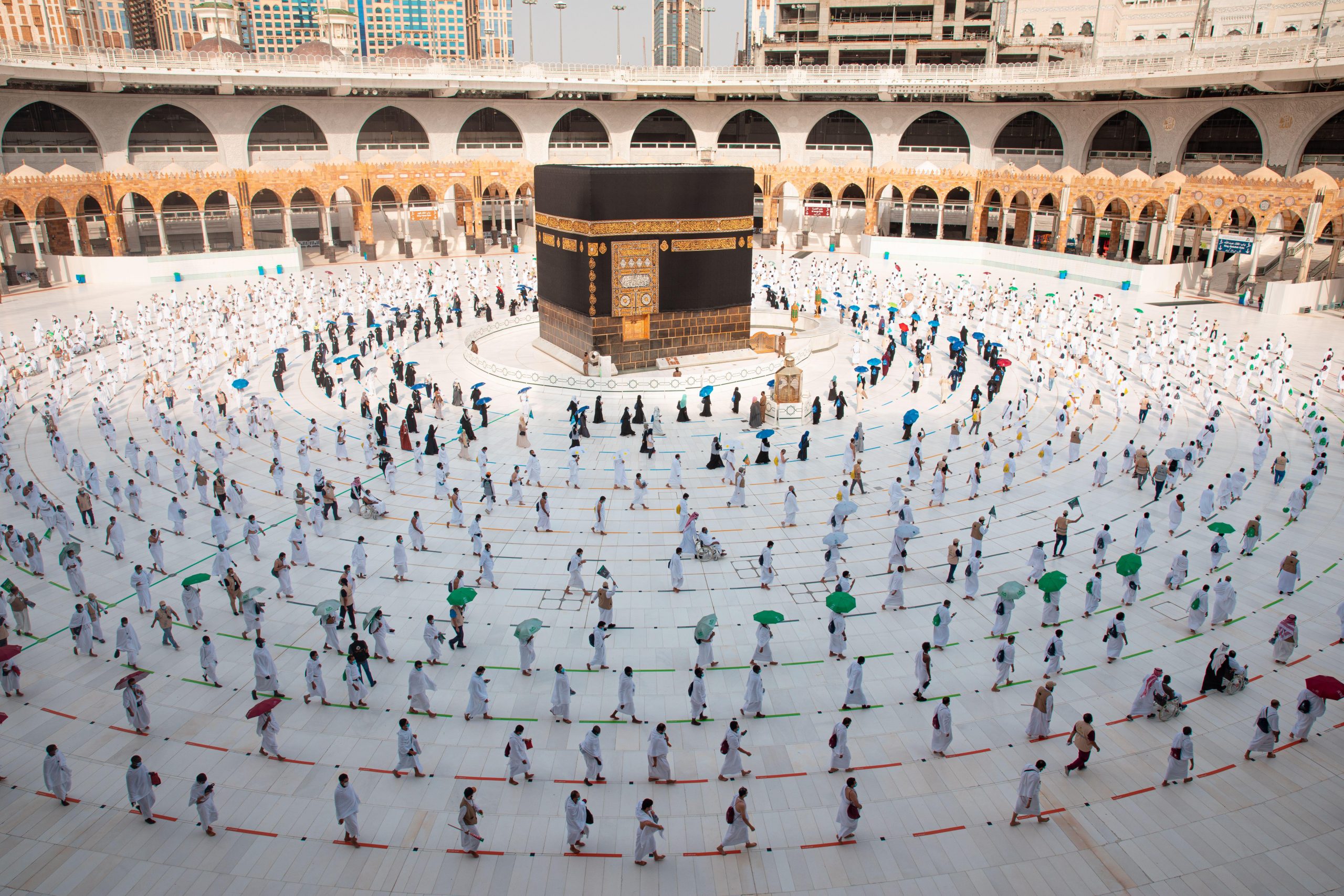

Invoking and praying to God count among the most common Islamic religious practices. While oral devotions can be uttered privately, the Friday communal prayer (salat al-jumu‘a) is of paramount importance for Muslim communities worldwide. However, in order to curtail or halt mass gatherings, nowadays Islamic prayer in congregational mosques tends to be livestreamed instead. Going one step further, in Kuwait the traditional call to prayer (adhan) was altered to urge devotees to stay at home rather than visit the mosque. Along with a number of other adaptations, including serious restrictions on the 2020 and 2021 pilgrimages (hajj) to Mecca, Islamic devotional traditions are flexible enough to accommodate prayer in a variety of outdoor spaces (Figure 1).

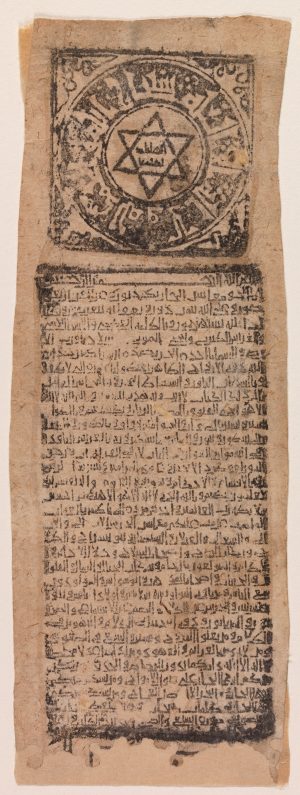

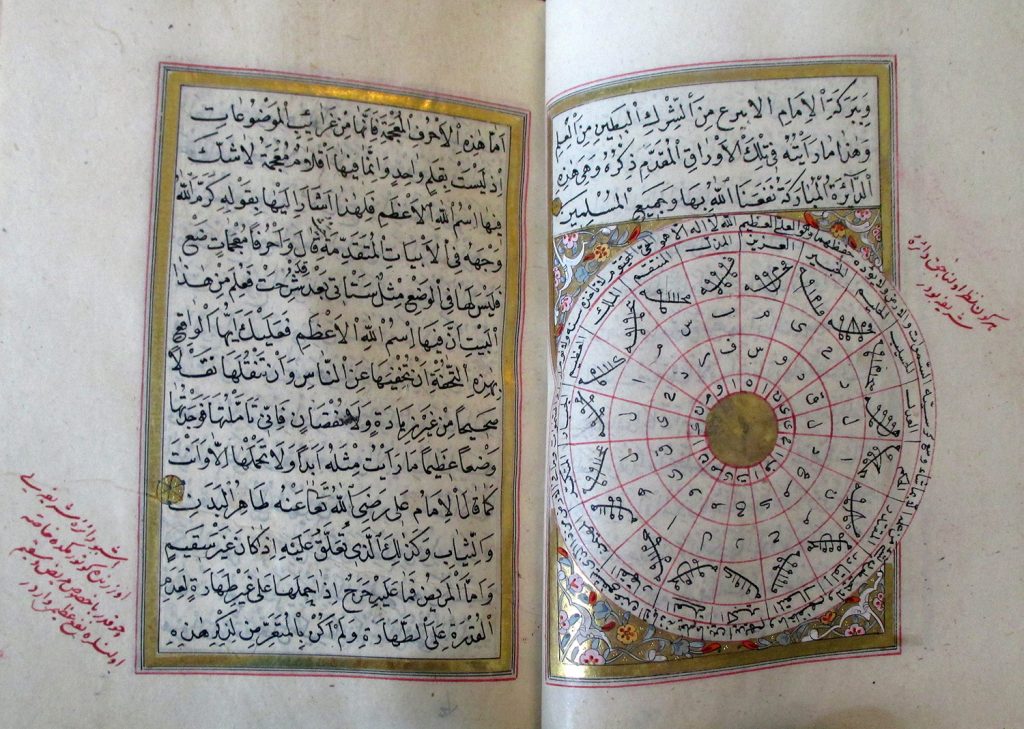

Within Islamic traditions a number of objects have been considered especially useful in protecting and healing individuals, including during travel and in the midst of epidemic outbreaks. Such artifacts include, above all, amulets and amuletic designs (Figure 2), healing bowls, and talismanic shirts. While these items tend to be classified as popular belief and even “superstition” per contemporary scientific thinking, they nevertheless emerged from spheres of elite knowledge, science, and art during the premodern period. Thriving in sub-elite and popular realms as well, the protective arts of Islam often breach through multiple barriers, including material and social ones. Most importantly, they showcase the human urge to seek protection and healing through the visual arts and material objects during arduous times.

Touching and Wearing: Amuletic Protection

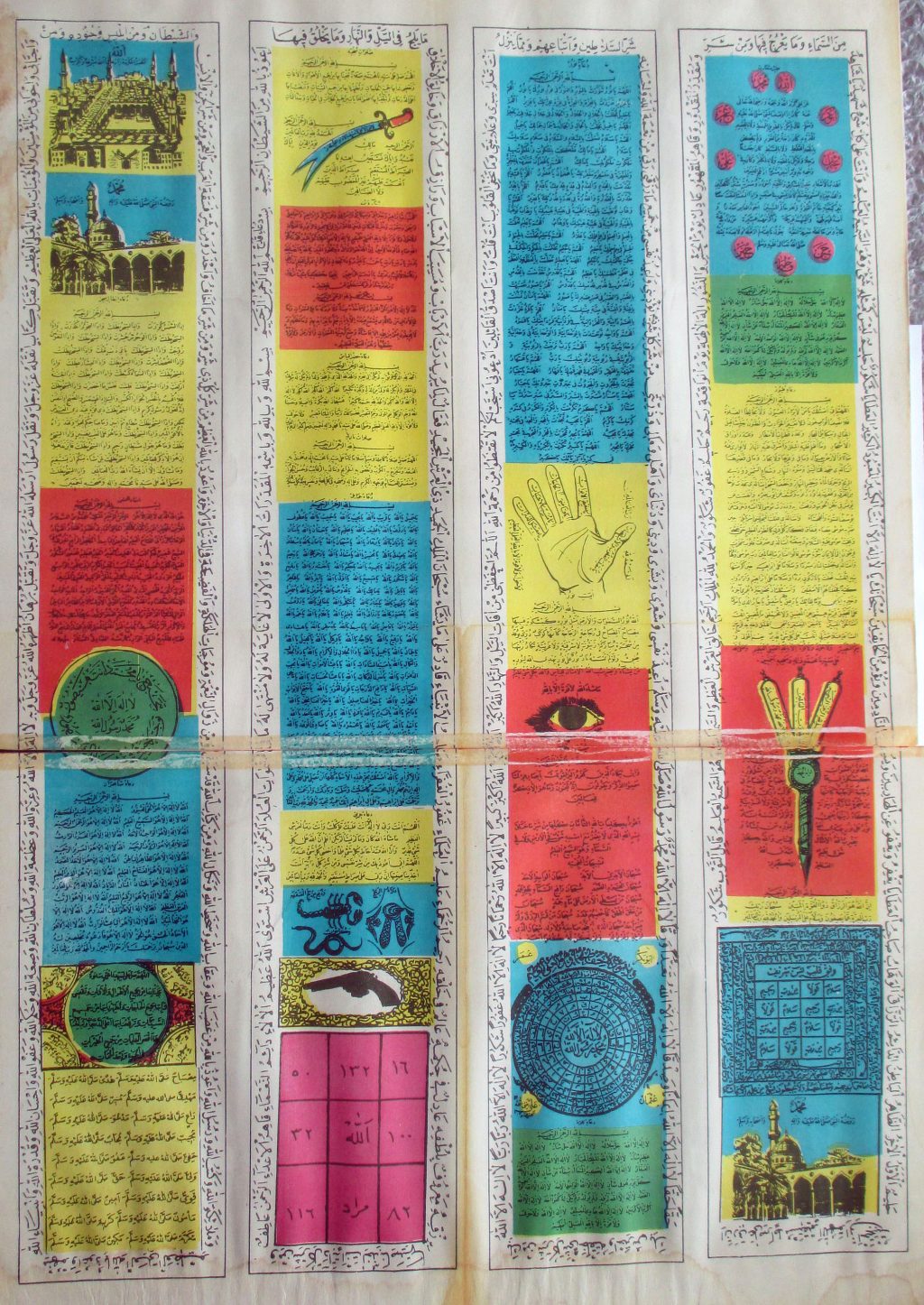

As in other global religious traditions, amulets and talismans have a long and rich history in Islam. Dating back to the eleventh century, the earliest surviving protective devices are talismanic scrolls containing Qur’anic verses, a number of which are considered particularly protective and curative. They also may include amuletic designs, such as the six-pointed seal of Solomon (Figure 3). Many block-printed paper scrolls made in Egypt attest to the affordability and thus relative availability of such objects during the medieval period. Moreover, that they were worn around the neck or attached to the body suggests that physical intimacy and contact were thought capable of unlocking the amulet’s blessings, a latent energy known as baraka in Islamic traditions.

Besides the seal of Solomon, a variety of amuletic designs can be found in scrolls, prayerbooks, metalwares, fabrics, and buildings throughout the Islamic world, especially from the fifteenth century onward. In royal and non-royal manuscripts, seal-like drawings and pictograms accompanied texts informing devotees that they could channel God’s blessings in the hopes of securing positive outcomes, such as protection from theft, drowning, and even death. In order to activate the seals’ defensive baraka, such texts encourage the owners to gaze, touch, rub, kiss, wipe, and carry such items while concurrently praying to and trusting in God.

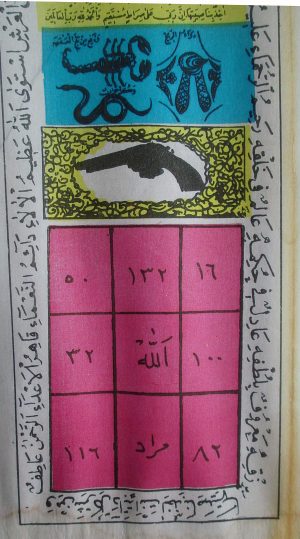

Over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, amulets also were printed and offered for sale in substantial numbers on the open market. For example, one large-scale modern talisman—pictured here before being cut into long strips and pasted together to produce a single scroll—compiles a wide range of protective verses, prayers, and graphic symbols (Figure 4). Among them can be detected the depiction of an eye followed by the Qur’anic verse (68:51) that mentions the harmful gaze of enemies. This visual and textual cartouche no doubt is intended to protect the talisman’s owner from the maleficent or “evil” eye cast (consciously or not) by those who might covet their happiness, health, or wealth. It also displays images that are intended to combat the toxic bite of scorpions and snakes, a representation of intestines accompanied by a “prayer of wind” to protect against flatulence, and a depiction of a pistol to secure physical preservation from gunshot wounds (Figure 5).

Beyond animal bites, food indigestion, and bullet wounds, perhaps most germane to our pandemic predicament is the anti-plague circular talisman known as the “Garden of Names” (jannat al-asma’). Attributed to the medieval Muslim philosopher al-Ghazali (died 1111 CE) but in fact a post-sixteenth-century development, the “Garden of Names” amulet contains nineteen letters and numbers that represent verses from the Qur’an and the “beautiful names” of God (al-asma’ al-husna) (Figure 6). At times, the seal’s accompanying texts invite viewers and owners to unleash the “noble circle’s” power in various ways. Such is the case for the anti-plague seal design illustrated Figure 6, which includes marginal comments stating that the seal is highly beneficial, especially for those who are sick or ailing, and that owners should gaze upon it every day and/or carry it on their physical selves in order to activate its latent properties. Still other texts provide directions for reproducing the talisman or display smudges, suggesting that viewers could kiss and rub the diagram or, alternatively, daub some water on the painted design to make an elixir of sorts (Bulmuş, 73, fig. 4.1). That the gold round center of the “Garden of Names” seal in Figure 6 sustains visible damage strongly suggests a haptic engagement by viewers and owners—whether it be through rubbing, kissing, or moist dabbling.

While such talismans might be deemed a thing of the past, the belief in the protective qualities of God’s names arranged in a seal-like form continues to press on in some circles today. For example, “Garden of Names” paraphernalia are sold by manufacturers of religious goods, who tout that such products can protect their owners from the evil eye, thieves, enemies, and many illnesses, including the plague (ta‘un). In some instances, “Garden of Names” amulets also are made as silver pendants combined with the opening (al-Fatiha) and chapter 122 (al-An‘am) of the Qur’an, both of which are considered particularly protective.

In these and other cases, talismanic objects do not merely belong to the magical or occult arts. Rather, they serve as a visual and material means to channel positive forces while urging the faithful to trust and seek refuge in an omnipotent God. They thus occupy a compromise position between the notions of free will and divine writ—a sliding scale that continues to endure in many religious cultures. Such talismanic objects nevertheless can be undermined from within or lambasted from without, as happened this past year when an anti-coronavirus amulet (muska) was sold in Turkey. An individual surreptitiously inserted an Arabic-script statement into the item’s commercials, which read: “The prayer of ripping off the gullible” (keriz yolma duası). This addendum furtively critiqued the muska—and its purveyors—as predatorial of those hoping to maintain good health in pandemic times by any means possible.

Further Reading:

Ahmed, Shahab. What is Islam? The Importance of Being Islamic, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2015.

Arjana, Sophia Rose. Buying Buddha, Selling Rumi: Orientalism and the Mystical Marketplace, Oxford, Oneworld, 2020.

Bulliet, Richard. “Medieval Arabic Tarsh: A Forgotten Chapter in the History of Printing,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 107/3 (1987): 427-348.

Bulmuş, Birsen. Plague, Quarantines and Geopolitics in the Ottoman Empire, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2012.

Dawkins, J.M. “The Seal of Solomon,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 76/3-4 (1944), 145–150.

Flood, Finbarr Barry. Technologies de dévotion dans les arts de l’Islam: Pèlerins, reliques et copies, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2019.

Göloğlu, Sabiha. “Linking, Printing, and Painting Sanctity and Protection: Representations of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem in Late Ottoman Illustrated Prayer Books,” in The Ascension of the Prophet and the Stations of His Journey in the Ottoman Cultural Environment: The Miraj and the Three Sacred Cities of Islam in Literature, Music, and Illustrated Manuscripts, ed. Ayşe Taşkent and Nicole Kançal-Ferrari, 485-505, Istanbul, Klasik Publications, 2020.

Gruber, Christiane. “Long before face masks, Islamic healers tried to ward off disease with their version of PPE,” in The Conversation, May 20, 2020.

Gruber, Christiane. “‘Go Wherever You Wish, for Verily You are Well Protected’: Seal Designs in Late Ottoman Amulet Scrolls and Prayer Books,” in Visions of Enchantment: Occultism, Spirituality, and Visual Culture, ed. Daniel Zamani and Judith Noble, 23-35, London, Fulgur, 2018.

Leoni, Francesca. “Sacred Words, Sacred Power: Qur’anic and Pious Phrases as Sources of Healing and Protection,” in Power and Protection: Islamic Art and the Supernatural, ed. idem, 53–65, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, 2016.

Perk, Halûk. Osmanlı Tılsım Mühürleri: Halûk Perk Koleksiyonu, 20, Istanbul: Zeytinburnu Belediyesi, Halûk Perk Müzesi, 2010.