This is the third of a three-part series on arts associated with protection and healing in Islam by Professor Christiane Gruber. Throughout the history of Islamic societies, ordinary objects have become vessels for connecting with the divine and seeking protection in trying circumstances. Just as in the present, when people around the world seek comfort in homemade remedies to alleviate their fear of the pandemic, historically during times of plague, amulets, blessed water, and even talismanic shirts have been drawn on for safety and healing.

Christiane Gruber is Professor and Chair in the History of Art Department at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; President-Elect of the Historians of Islamic Art Association; and Founding Director of Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online. Her fields of interest include Islamic ascension texts and images, depictions of the Prophet Muhammad, book arts, amulets and talismans, codicology, paleography, architecture, and visual and material culture from the medieval period to today. Her latest publications are her third monograph The Praiseworthy One: The Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Texts and Images (2019) and her edited volume The Image Debate: Figural Representation in Islam and Across the World (2019).

Personal protective equipment—whose acronym “PPE” now forms part of our daily lingo—has arisen as a pressing concern during this pandemic period. Fighting on the frontlines against the spread of epidemic diseases, nurses and doctors don protective clothing, goggles, face masks, and other equipment in order to shield themselves from harmful and killer entities such as coronaviruses. Protective armor is typical in the arena of war as well, and indeed today the “fight” against COVID-19 is frequently spoken of as a struggle against an invisible enemy.

Intriguingly, in the Arabic language the term for plague (ta‘un) is derived from the verb to “pierce” or “strike” (ta‘ana), linguistically engaging a martial metaphor as well. Before the articulation of the germ theory of disease in the nineteenth century, in Islamic lands epidemics were conceptualized by many as a pestilential corruption of air, through which black angels shot invisible arrows and humid spirits entered the bodies of human beings.

To avoid both real and spiritual smiting, Muslim patrons—typically of royal or elite rank—turned to wearing talismanic shirts, the quintessential premodern Islamic “PPE” (Figure 13). While such garments contain a variety of inscribed content, a group of shirts made in South Asia around 1450-1550 CE display the entirety of the Qur’anic text laid out in rectangular panels suggestive of sheets of paper extracted from a bound book (Figure 14). In this regard, both their execution—via the inking of content on a starched cotton surface—and their aesthetic look inch closer to the calligraphic and book arts rather than the textile arts, where weaving, knotting, and embroidery take precedence. They thus function as vestmental amulets, cloaking and protecting the human body secreted beneath.

These shirts’ borders also enumerate God’s beautiful names, acting as a “textile rosary” (Muravchick, 686) that somewhat recalls the brass tags of healing bowls (see figures 7-8 in the second essay). Moreover, their pectoral roundels, shoulder pads, and lapel-like fringes emulate metal and lamellar armor. Acting like a metal sheath or bulletproof vest, their back-protector panels tend to be inscribed with the Qur’anic verse (12:64) stating that “God is the Best Guardian and the Most Merciful of the Merciful Ones” (Figure 15). This verse provides further symbolic protection—in this instance, granting ultimate power to God and couching Islam’s holy book as sacred safeguard.

As mentioned above, invocations of God and Qur’anic verses are inked onto the surface of each garment. This process of manufacture can result in ink loss through water damage, while segments of cloth can be torn in physical confrontation. Although a number of talismanic shirts appear intact, even pristine, some display clear signs of wear and tear. Among them, one shirt (Figure 15) includes areas of brownish smudging, while another shirt suffers from a substantial smearing of ink within its armpits (Figure 16). That such damage appears in the underarms confirms that the shirt was indeed worn, the wearer’s perspiration causing a rather cloudy concoction. More than just a blemish, this admixture of liquid ink and bodily excretion could also be conceptualized as yet another philter: that is, incubated words to be absorbed into the human body. Unlike the baraka-water of healing bowls, this type of philter could be soaked up by the pores of the flesh rather than imbibed through the mouth.

From the past to the present, protective encasing spans the gamut from premodern talismanic shirts to medical isolation gowns, stretching from the field of devotion to the realm of medicine. Within the protective arts, Islamic amuletic shirts were considered capable of preserving a person at a physical level via spiritualized thinking and objecthood, and not through trial tests and patent approvals. In these physical and material efforts to harness and channel defensive energies, the emphasis instead remains squarely focused on man’s dependence on divine will and authority, with God acting as the ultimate protection against various ills and attacks, including pandemic ones.

Restoring Balance

The protective arts of Islam point to the human drive to seek protection and healing through allegorical thought and behavior, both of which are often imaginative and resourceful. From amulets to bowls and shirts, these occult-scientific artifacts nevertheless could—and, in some cases, still do—supply a spiritual sheathing to those in need of further strength and sustenance. In moments of illness or epidemic outbreak, individuals may view such objects as providing a potential balm of relief. In such cases, a placebo effect may influence the mind and body, a phenomenon that otherwise remains inexplicable according to the method and logic of contemporary medicine.

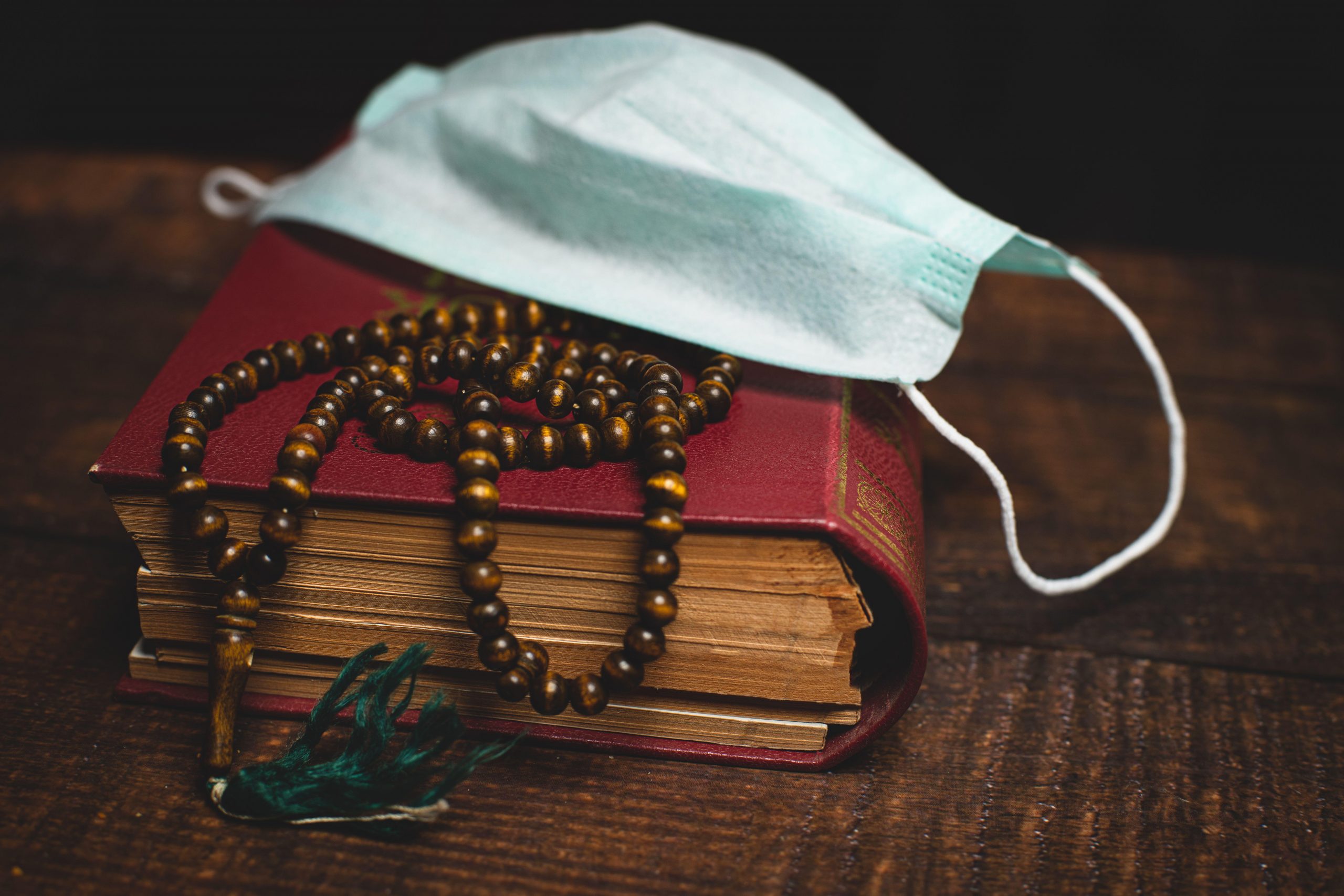

A turn to piety comprises only one possible reaction and throughout the ages “it was not the sole principle dictating how people would behave when facing a major epidemic” (Ayalon, 184). Other responses included various medicinal ointments and containment strategies that effectively reduced the spread of contagious diseases. Science and devotion therefore could be mutually reinforcing rather than at odds. For centuries, individuals have turned to both arenas of belief and practice in the hopes of doubling positive results (Figure 17).

Further Reading:

Anetshofer, Helga. “The Hero Dons a Talismanic Shirt for Battle: Magical Objects Aiding the Warrior in a Turkish Epic Romance,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 77/2 (2018), 175-193.

Ayalon, Yaron. “Religion and Ottoman Society’s Responses to Epidemics in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” in Plague and Contagion in the Islamic Mediterranean, ed. Nükhet Varlık, 179-197, Newark, Arc Humanities Press, 2017.

Braque-Perrière, Eloïse. “Les tuniques talismaniques indiennes d’époque pré-moghole et moghole à la lumière d’un groupe de Corans en écriture bihari,” Journal Asiatique 297/1 (2009), 57-81.

Conrad, Lawrence, “Ta‘un and Waba’: Conceptions of Plague and Pestilence in Early Islam,” Journal of the Social and Economic History of the Orient 25/3 (1982), 268-307.

Cunningam, Graham. Religion and Magic: Approaches and Theories, New York, New York University Press, 1999.

Fotheringham, Avalon. “Guest Post: A Warrior’s Magic Shirt,” Victoria and Albert Museum, June 17, 2015.

Muravchick, Rose. “Objectifying the Occult: Studying an Islamic Talismanic Shirt as an Embodied Object,” Arabica 64/3-4, De-Orienting the Study of Islamicate Occultism, ed. Matthew Melvin-Koushki and Noah Gardiner (2017), 673-693.

Tezcan, Hülya. Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Koleksiyonundan Tılsımlı Gömlekler, Istanbul, Timaş, 2011.

Tezcan, Hülya. Topkapı Sarayı’ndaki Şifalı Gömlekler, Istanbul, Euromat, 2006.