The following is a guest post by Amanda Caterina Leong, a Ph.D Candidate in Middle Eastern Studies at the University of California, Merced’s Interdisciplinary Humanities Program. Her research looks at the ways early modern women from Safavid and Mughal Empires were central to defining notions of ethics, power and empire-building that shaped the early modern Persianate world.

“If anyone should run out from the quarantine, or come into the city without performing quarantine, he would be put to death […]. The law of the Franks does not inflict death as a common punishment, but punishments are either fines, imprisonment, or banishment.”

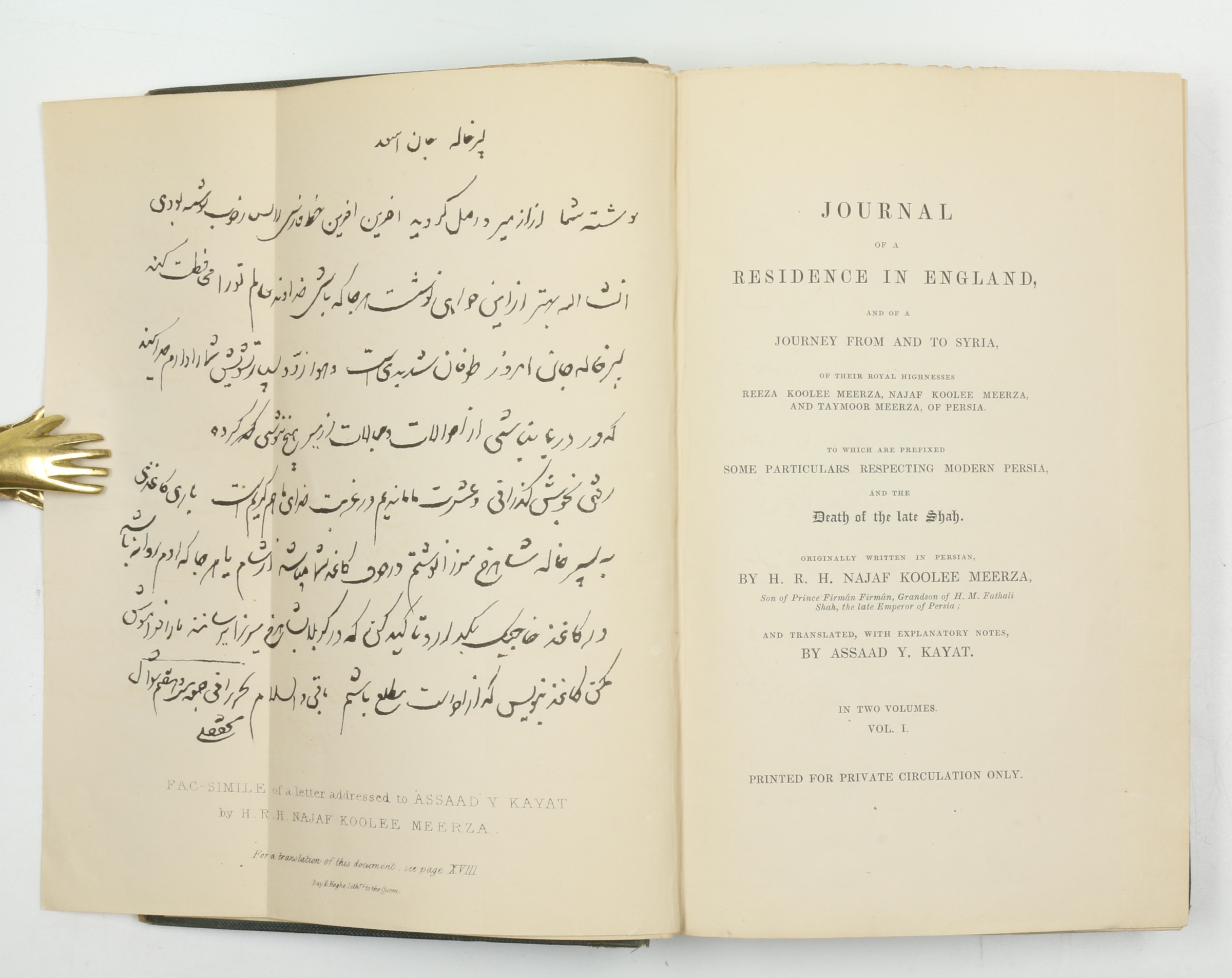

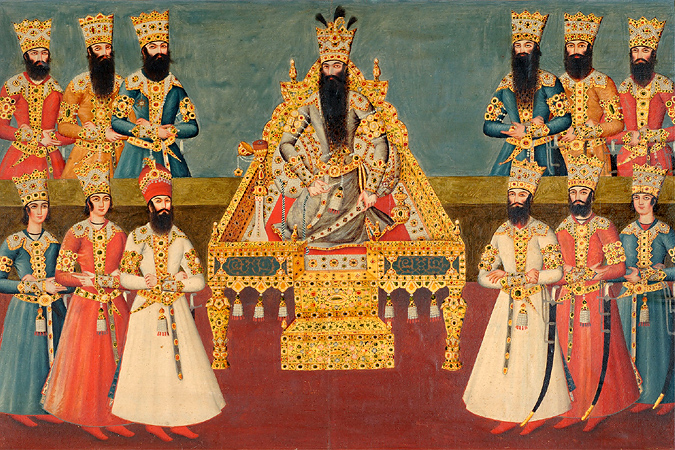

Najaf Koolee Mirza, an Iranian prince from the Qajar Dynasty and grandson of Fath Ali Shah, penned these words in his travelogue that was translated and published as Journal of a Residence in England and of a Journey from and to Syria: of their Royal Highnesses Reeza Koolee Meerza, Najaf Koolee Meerza, and Taymoor Meerza, of Persia in the 1830s while in quarantine in Malta, a British colony off the coast of North Africa.

At the time, the world was undergoing a cholera pandemic that killed millions of people across all continents. Najaf was traveling en route to England with his two brothers to solicit British assistance in liberating his imprisoned father, Firman Firman, who had lost the war against Mohammed Shah to become the next king. He was one of the first Iranian royals to visit Great Britain. But before being allowed to enter England, he had to quarantine in Malta.

In England, breaking quarantine was considered a serious offense, holding one liable to be “condemned as crimes to death” – much of which can be linked back to the cholera pandemic in the nineteenth century that killed millions of people across continents and continues today. In fact, according to Najaf, quarantine was utilized as one of the strongest tools against pandemics like cholera by European nations and became so ingrained within society that it exceeded the realm of law and extended into the afterlife. He argued that it had become common belief that one’s violation of quarantine would subject them to eternal damnation:

“The law of quarantine with the Franks is an important article of faith in their religion; if they break it, according to their belief, they will be punished in the last great quarantine.”

Ironically, it was British expansion that was originally responsible for disseminating cholera to the rest of the world. British troops from Bombay brought cholera to Iran for the first time in 1821. Unfortunately for Iran, the cholera pandemic lasted until 1830 and spared no one from rich to poor, killing around a quarter of Tehran’s population until it gave way to one of the country’s worst spates of bubonic plague. The world during the nineteenth century when the cholera pandemic broke out shares similarities to the COVID-19 present we are living in today.

Najaf’s travelogue belongs to the Persianate literary tradition of safarnama (travel writing). Safarnamas often focus on themes like travelers’ encounters with wonders (‘aja’ib), the beauties of cities and people (shahrashub) or the introduction of new forms of discourse such as the benefits of modernization and technology. Najaf’s stories and recollections regarding his experiences in quarantine nearly 200 years ago are valuable because they help us understand that although we may have thought that we had advanced far beyond that time, the failures of countries around the world to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic at present reveal how much has in fact stayed the same – and the lessons we can learn from past pandemics are as applicable today as ever.

Quarantine lesson 1: What is quarantine?

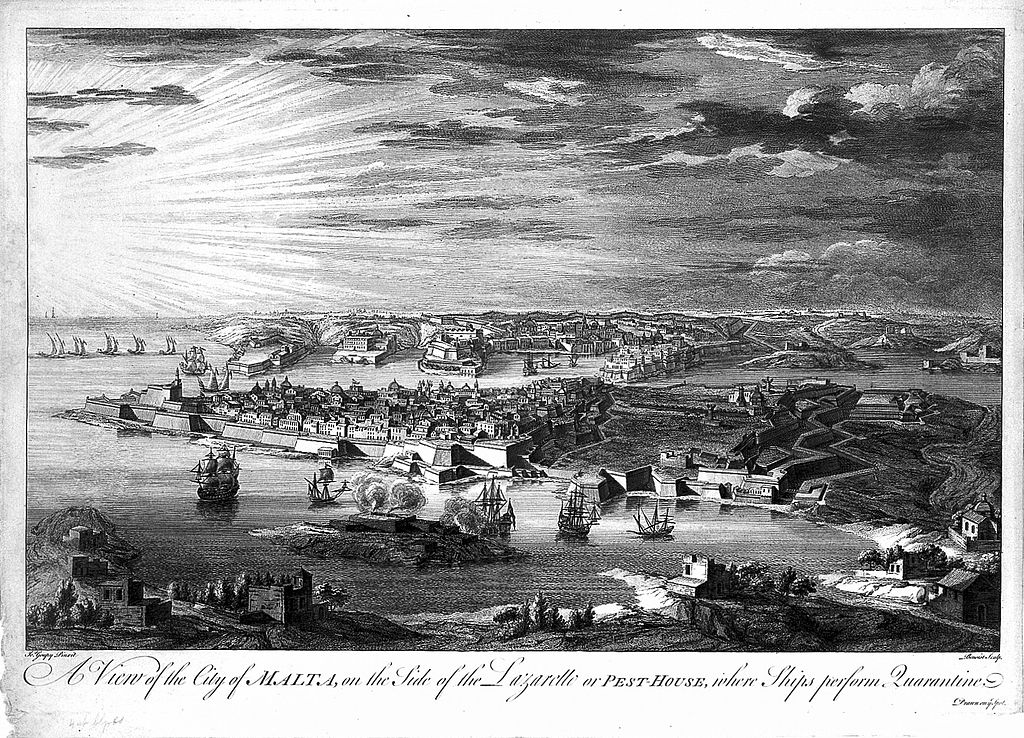

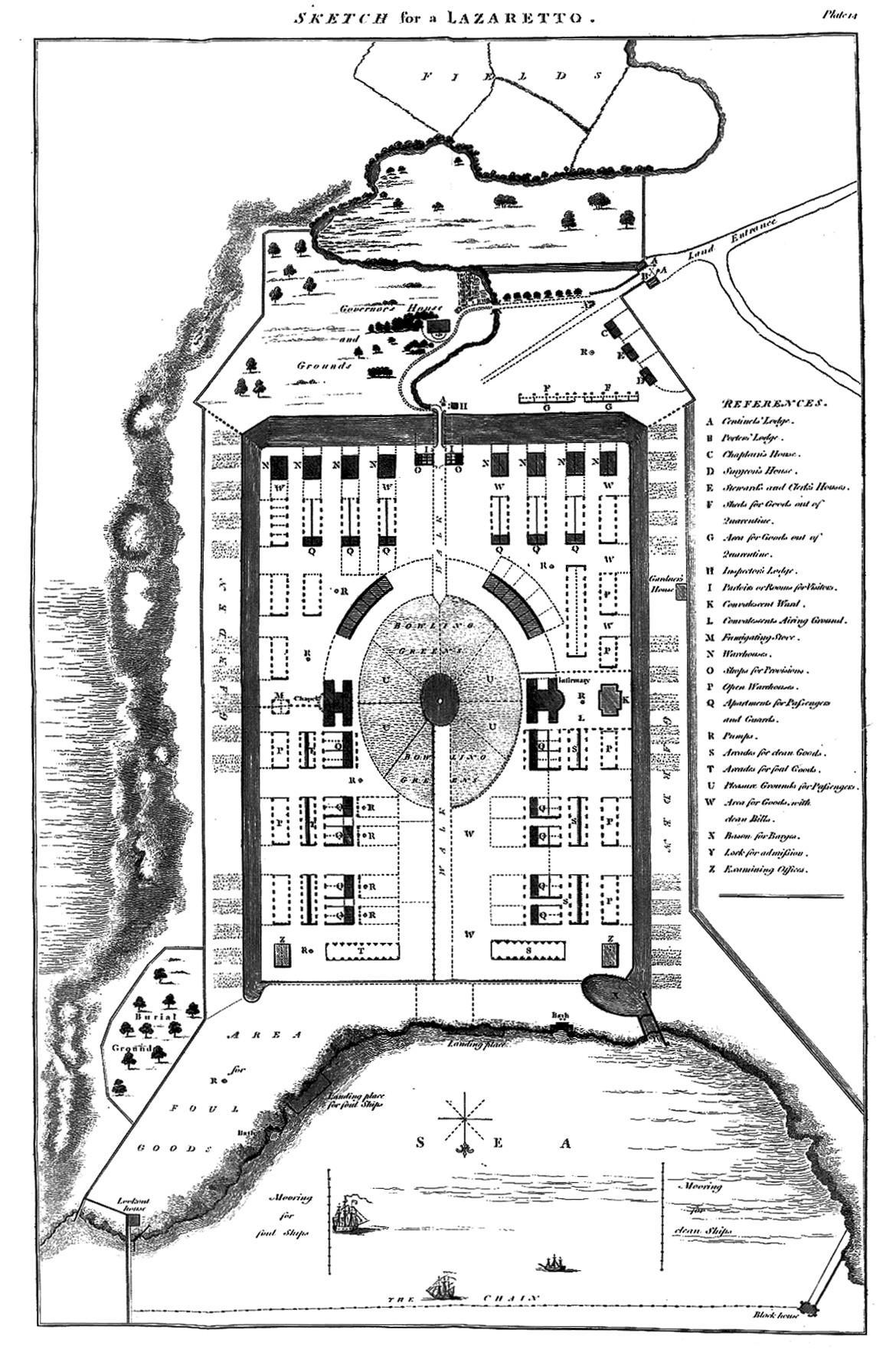

“The quarantine, or the Lazaretto, is a very strong, large edifice, and very lofty. It is established on the account of the plague and other contagious diseases. In every kingdom of Europe there are different opinions in regard to the period of time necessary to observe quarantine. Some demand forty days, others a month; in Malta it is twenty-two days. The establishment is built on a place opposite the city, and separated from it by the quarantine harbor […] The regulations of quarantine are as follows: Whenever a vessel comes near the isle, it must hoist a yellow, bad-looking flag, which is the quarantine color. When it comes near the anchorage, it must communicate with nobody […]. Even those in quarantine could not communicate with each other, except those who have arrived together, or those whose quarantine have the same length […] Should persons of different periods of quarantine communicate with each other, they must all perform that quarantine which is the longest. After they come to the Lazaretto, they must open all their clothes, and everything they have, to the air; the captain of this establishment must see every day that this is done; if anything were left unopened, the time of quarantine would be lengthened.”

From his detailed and intricate description of quarantine procedures, Najaf encourages potential leaders reading the text to embrace teachings from different cultures when it comes to implementing models that can stop the transmission of pandemics. This is particularly important in our COVID-19 present where we have political leaders denying the existence of COVID-19 and refusing to believe in scientific expertise, thus failing to control the COVID-19 pandemic.

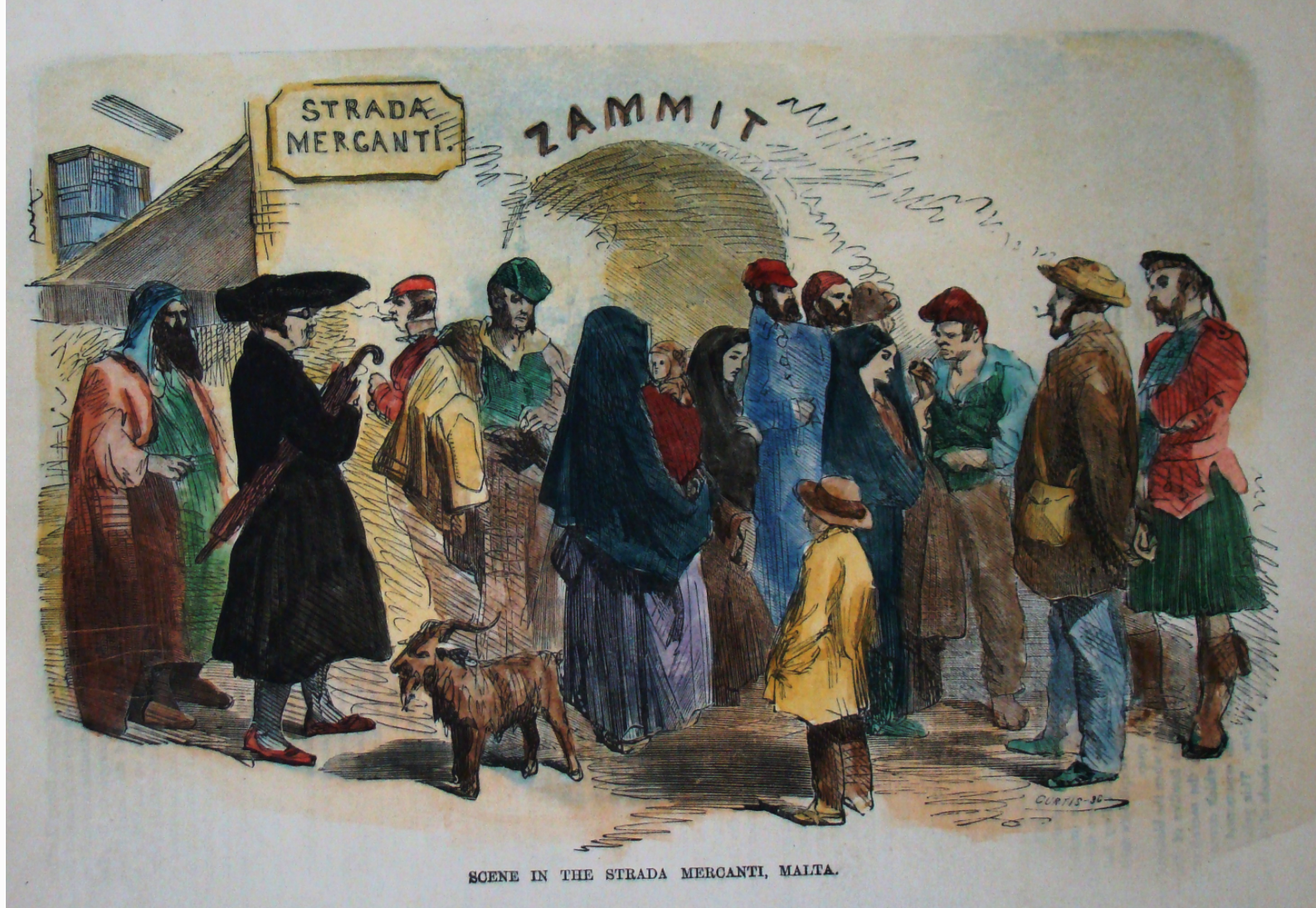

Moreover, by depicting how selfishness and ignorance during times of quarantine are severely punishable by law, Najaf reminds readers of the severity of pandemics and the need to be vigilant and cooperative with public health regulations. Most importantly, in describing quarantine in Malta as strictly imposed on foreigners before they could enter Britain and how it was not enforced domestically, we are also able to see how quarantine in this context was also used for biopolitical purposes. Even though it was originally British forces that spread the contagion around the world, the need to to control bodies from “East” due to the fact they were backwards, helpless, and unclean reveals an Orientalist fantasy for dominance that continues to be propagated by the media today.

Quarantine lesson 2: Love can kill

Najaf relays a tragic love story between a Turkish traveler who fell in love with a lady in Malta only for him to accidentally kill both of them. This Turkish traveler forgot to disinfect a diamond ring contaminated by the plague virus that he had given to his lady love. Upon wearing her new gift, the lady fell victim to the plague and not only passed it to her lover but also infected other people around them. Najaf’s travelogue thus emphasizes the highly contagious rate of pandemics like the plague and reminds readers the need to adopt sanitary measures to prevent them:

“A few years ago, a fine educated and rich young Turk, named Hassan Aga, left Smyrna for Europe, for the purpose of trading and traveling. After taking pratique, Hassan Aga landed at Valletta, and, while walking around town, his eye fell upon a young lady […] Hassan, as a token of his love […] presented his beloved with a diamond ring, which he had on his finger. The ring having been too large, by unforeseen predestination, he had tied a thread around it, which during the time of his performing quarantine, he had neglected to air or have it smoked; Hassan’s constitution not being then susceptible, he did not take the plague; but now the ring put on the lady’s finger, while the heat of her blood was at the highest, the plague immediately infected her, and she communicated it to the young man. The consequence was that both of them died soon after. From them the people of the place became infected, and infected others, and a great number of people of the city of Malta were destroyed by the plague. Irrational animals may take the plague, and communicate it to man, but it does not affect them. This disease rages in the temperate climates. During the extreme cold and heat, it diminishes, and grows mild, but it does not entirely disappear.”

The reliability and authenticity of the tragic love story is not altogether clear. But the highly scientific rhetoric Najaf employs in his telling of the story reflects a medical understanding of how pandemics unfold, whether or not it is completely accurate. He reminds us that transmitters of viruses can be asymptomatic in the way they “are not affect[ed] by [the plague].” Furthermore, Najaf is aware of the connection between environmental changes and virus transmission during pandemics.

Najaf’s scientific mindset when relaying a love story reflects how, as a result of unique historical circumstances such as Western influences and Islam’s own evolution that underwent “a cultural and philosopher efflorescence that endorsed individualism, as well as the pursuit of literature and science,” fields such as medicine, hygiene, science, worked alongside literature and religion to shape a Qajar imperial mindset like that of Najaf. This is further seen from the way Najaf, writes in another part of his travelogue, how religion served as a pillar of strength that helped them overcome the negative emotions they felt during quarantine: “Sunday the 7th, Monday the 8th, and Tuesday the 9th, we were at the quarantine engaged in performing the prayers of Ashoora, reading the Holy Book, with thanks to the Most High, and awaiting the end of our quarantine.” Religion and science are not depicted as opposing camps but in fact, should be used by Iranian rulers to perform good kingship for the sake of public health.

Quarantine lesson 3: Quarantine is a privilege

“There are a great many apartments in this Lazaretto; […] God protect! If anyone should break the law of this place, or do anything contrary to its regulation, though it should be the emperor of all the face of earth, and offer millions of money, it would not be accepted; nor could he escape the punishment.”

By stating how no one, regardless of their wealth, “millions of money” or status, “emperor of all the face of earth,” can escape undergoing quarantine, Najaf reminds leaders to forget about their privilege, but instead embrace being good role models for the public to follow in order to successfully fight against pandemics to follow regardless of how it goes against what their privilege has taught them. In addition, Najaf reveals how pandemics reflect inequalities between the powerful and the poor, especially when it comes to being able to afford quarantine. This is seen from how he talks about how normal passengers arriving in Malta for quarantine are required to “take apartments furnished, which they must pay for.” On the other hand, elite princes like him and his brothers are provided “a spacious, lofty apartment […], furnished with everything” without being charged. This inequality is continued in real time as seen from how countries and people in power are benefiting from the pandemic with the rules of quarantine not equally applied.

Quarantine lesson 4: Bored during quarantine? Try new food!

During his period of quarantine, Najaf mentions the difficult emotions he experienced: “Thursday the 11th, we were quite depressed.” We can see how similar the past and present really are, with the feeling of boredom being universal and confinement leading to lethargy. He shows the readers new methods he used to pass time, specifically by trying new and different foods. Here is an entry of him trying out strawberries, a fruit unfamiliar to Iranians at that time and which is today called in Persian tut farangi, “Frankish berry.”

“We found, among the fruits that the captain sent us, a new kind of fruit which we had never seen before, very soft to the touch, of a red colour, like that of the mulberry, the seeds very delicate; it is of sweetish taste, which they eat with pounded sugar; they call it strawberries.”

Apart from strawberries Najaf also talks about his first time eating food preserved in tin cans as part of their quarantine culinary experience:

“The English men of war which navigate in the Great Sea, and in the New World, and for a year do not see or touch on land, carry with them this flesh, which is prepared by some chemical process, and it is then put into cases which are carefully stopped, so that air may not injure it, and by this means it remains as fresh as in its original state, and is eaten as if it were fresh. We were quite astonished at this description, and ordered our cook to come, and we gave him some of this fish to wash and cook. When it was brought to dinner, we found it superior to any fish we ever ate.”

From his description of strawberries and positive remarks regarding canned fish that he sees as “superior to any fish we ever ate,” we are able to see how Najaf was able to use the trying of new food as a way to confront quarantine blues, to redraw the restrictive space of quarantine. With this, he shows readers the mindset they should have during times of pandemics, which is to stay positive and to make the most out of their times in quarantine.

According to Assaad Y. Kayat, the Lebanese-Christian translator who accompanied them during their journey to England and and wrote the preface to Najaf’s published travelogue, Najaf and his brothers became “the first members of the Persian royal family that ever visited England” and were successful in soliciting British support to help their father. Most importantly, Najaf’s travelogue that was widely circulated in both Iran and Britain, became a valuable book that taught readers the importance of learning from the past and from those who are different, in order for a better present, as seen from Kayat’s words:

“It is rare that the English Public obtain such an opportunity of learning what is said of them by the people of other nations, as in the work now presented. It is not uncommon to have European travellers in this country; but to have Asiatic travellers, men of distinction, who write their views on all they have observed, is a singular phenomenon. Such a work may teach by comparison the state of civilization to which Britain has attained […] And we may learn further, what a vast interest might accrue to the English nation, and what great benefits may be conferred upon the East, by visits like this, of three Mohammedan Princes of royal blood, or other personages of distinction.”

References

Afkhami, Amir. A Modern Contagion: Imperialism and Public Health in Iran’s Age of Cholera, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018.

Najaf-Kuli Mirza, and Assaad Yakub Khayyat. Journal of a Residence in England, and of a Journey from and to Syria : of Their Royal Highnesses Reeza Koolee Meerza, Najaf Koolee Meerza, and Taymoor Meerza, of Persia. To Which Are Prefixed Some Particulars Respecting Modern Persia, and the Death of the Late Shah. Farnborough: Gregg, 1971.

Kashani-Sabet, Firoozeh. “Hallmarks of Humanism: Hygiene and Love of Homeland in Qajar Iran.” The American Historical Review, vol. 105, no. 4, 2000, pp. 1171–1203. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2651407.

Micallef, Roberta., and Sunil Sharma. On the Wonders of Land and Sea : Persianate Travel Writing . Boston, Massachusetts: Ilex Foundation, 2013.