The following is a guest post by Maya Reus, a master’s student in Near and Middle Eastern Studies at SOAS, University of London. Her research focuses on social history and visual culture in Iran and Turkey. Follow her @_marca_pola.

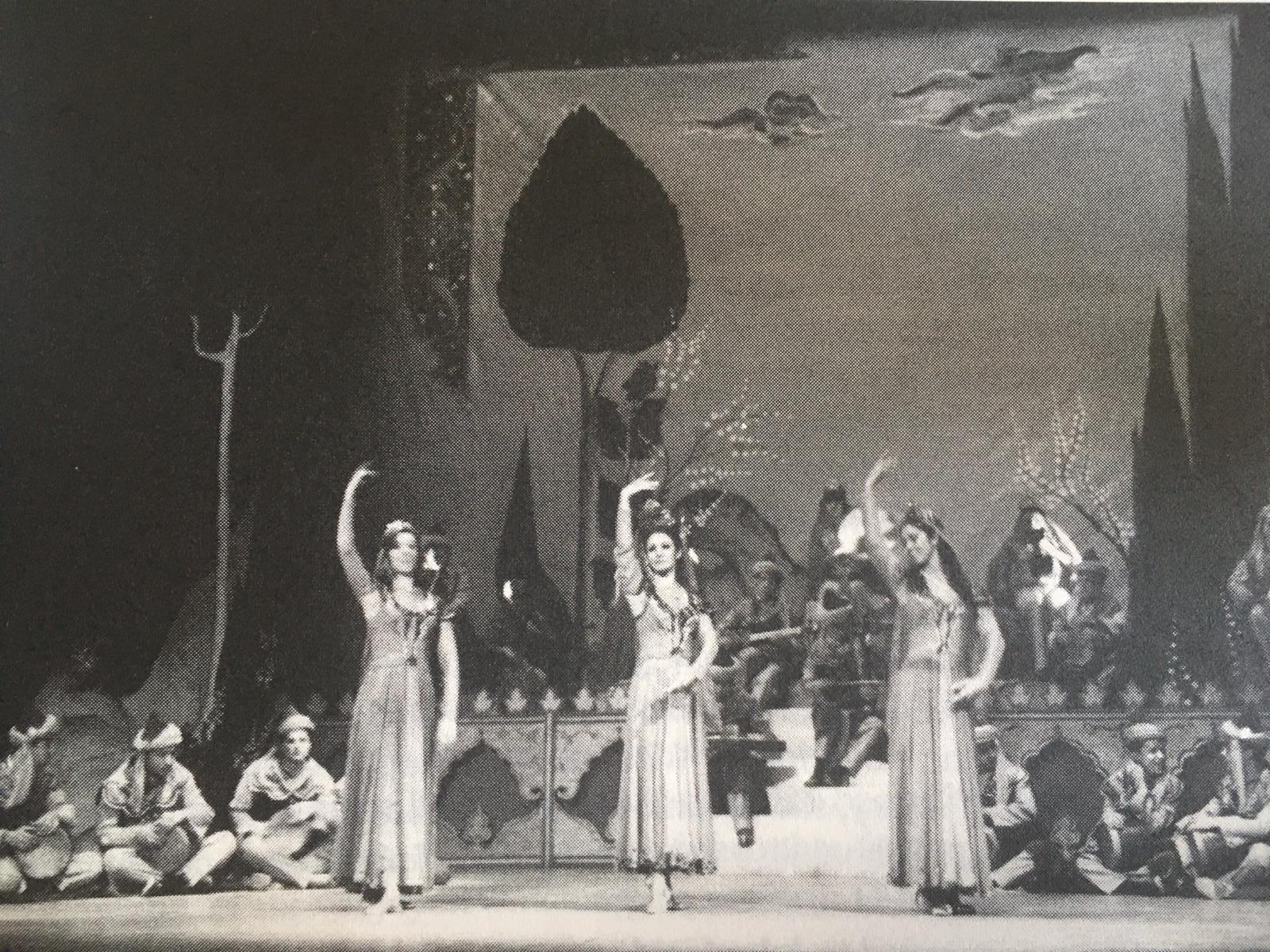

Tehran, 1946. Three women step onto the stage of a public theatre. Nesta, Haideh and Wilma are clad in fantastical renderings of folk outfits that mirror the colours of the desert, ready to perform a dance called the Caravan.

It was a brave undertaking: never before had women of well-to-do families danced on a public stage in Iran. The audience was taken on a visual journey in which the three women performed a mystical dance, combining improvisation, modern ballet and folk dance. Inspiration for the dance was taken from a poem of Saadi, one of the most beloved poets of the Persian canon:

ای ساربان آهسته رو کآرام جانم میرود وآن دل که با خود داشتم با دلستانم میرود

O Caravan move slowly, for the peace of my soul is leaving,

The heart that was mine before, with the charmer of hearts is leaving

در رفتن جان از بدن گویند هر نوعی سخن من خود به چشم خویشتن دیدم که جانم میرود

The wise have never agreed on the parting of soul and body,

How have I with my own eyes seen my soul in its leaving?

The Caravan marked the beginning of the Studio for the Revival of the Classical Arts of Iran, a dance company that became highly successful in embodying the modernist idea of Iran as an ancient nation. In light of the studio’s focus on Iranian nationhood it was curious that the mastermind of the dance company was the American Nilla Cram Cook, the cultural attaché of the U.S. embassy in Iran and an orientalist scholar in both senses of the word. As recounted by Nesta, one of the dancers, in her memoir ‘The Dance of the Rose and the Nightingale’, Nila strove to ensure that the dances performed by the group were rooted in Iranian history and poetry, thus becoming a “celebration of Iran’s great past.”

The project was also highly gendered in its portrayal of Iran as a nation: whereas for centuries public dance had mostly been associated with young men, the troupe stressed that Iran had a modern style of dancing in which women were in the public limelight. In doing so, the Studio for the Revival of the Classical Arts of Iran presented a sharp turn from the past state of dance in Iran, which their members saw as degenerate and base rather than a form of art. In Nesta’s words, they instead set out to “restore” dance to the “stages of Iran.” In this article, I explore how the studio invented a style of Iranian dance that was completely modern and yet presented as deeply rooted in the past, in the process inventing tradition and re-imagining dance culture in modern Iran.

“Reviving” Performance, Erasing Dance History

Although they presented their work as “reviving” Iranian dance, dance performance had always flourished in Iran, past and present. Dancers were often organised via the organisational unit of the motreb, a troupe that could include musicians, dancers, acrobats and actors. In the Qajar era (1789-1925) lots of dancers of motrebs were ‘dancing boys,’ who performed in houses of royalty and notables, and in public places such as coffeehouses and on the streets.

Historian Afsaneh Najmabadi has argued that Iran at the time could be defined as a “homosocial” society in which, at least in urban centres, women socialised with women and men with men, and where the public space was dominated by men. This carried over into the world of dance as well. Dancing boys were known for their acrobatic skills as well as for their beauty, including traits now often associated with femininity such as wearing dresses and makeup. In the private sphere, women performed for women, and there are some limited accounts of women performing for men. The contributions and acrobatic skill of women dancers and entertainers should not be underestimated, as testified by the numerous Qajar-era paintings of women in spectacular balancing positions.

These types of dance most likely seem to have continued into the Pahlavi era (1925-1979). In the 1940s, another type of dance seems to have become popular in Iran; in Tehran’s down-town café district, women also danced for men in what is called ‘cabaret’ style, a more westernised form of dance that became increasingly associated with dens of ill-repute on streets like Lalehzar or the red light district, Shahr-e No.

Although beloved by the audiences they performed for, the status of motrebi musicians and dancers has probably been ambiguous throughout history. Dance historian Anthony Shay has coined the term ‘choreophobia’ to characterize dubious attitudes towards dancers. He states that one of the reasons for this was the fact that the realms of the sex and entertainment industry overlapped, with both considered as part of the ‘seedy underbelly’ of society. Some Islamic scholars considered the act of dancing to be improper, in part because of this association, but also because it would detract from religion (althought it has been suggested that this view was not different before the onset of Islam). People that performed professionally were sometimes considered as ‘fringe figures,’ and were often non-Muslim, nominally Muslim, or from lower strata of society, including from Kowli communities (sometimes referred to in English as “g*psies”).

During the Pahlavi dynasty (1925-1979), many modernists regarded motreb and cabaret style dancing as overtly sexual and morally improper for a modern Iranian nation, in part reflecting European criticisms of Iran (and the Middle East more broadly) as a highly sexualized and morally scandalous region. The dancing boys in particular came to be seen as hypersexualised and effeminate, reflecting conservative norms of European gender and sexuality that increasingly saw presentation of male beauty and dance in public as improper and which saw homosexuality as an illness to be eliminated. These ideas were taken up by many Iranian intellectuals, who saw the homosocial practices as embarrassing relics of a past that did not properly conform to European norms of gender, which they saw as universal and modern.

Imagining the Past, Inventing Tradition

It is no surprise then that Nila, the American in charge of the Studio for the Revival of the Classic Arts of Iran, made sure her dance company would depart from motreb style dancing, and would instead present Iran in a way that aligned with nationalistic tendencies and Western norms of public heterosexuality. Both Nesta Ramazani and Haideh Ahmadzadeh have recounted their journey as dancers for the studio in their memoirs, and their stories give insight into this strategy.

Both women, together with their friend Wilma Protiva, were students of Mme Cornelli, a dance teacher who had immigrated from Russia and had brought knowledge of classical ballet to Iran. The women themselves had international backgrounds too: Nesta’s mother was English, Haideh’s parents had also immigrated from Russia, and Wilma was the child of Czech immigrants. All of them were educated at international schools. Later on more women would join the dance troupe, some of them picked up in countries where they toured. In spite of these transnational backgrounds, they invoked symbols of Iranian nationalism in their dance performances. They hoped by drawing on these symbols, they could anticipate and overcome public disapproval of women’s presence on stage and revolutionize norms of gender and respectability around dance and performance more broadly.

In order to comply with Western norms of public heterosexuality, the group’s performances would be heterosocial rather than homosocial, and would focus on women performing for mixed audiences while marginalizing men’s ability to perform. Secondly, their performances would both mirror and contribute towards a swathe of symbols and narratives that were popular and promoted by both Iranian state-backed intellectuals and Western orientalists as part of Pahlavi-era nationalism.

This type of nationalism pivoted around different points of reference that represented Iran in a “presentable” way to the West: Iran’s glorious pre-Islamic past with its Achaemenid and Sasanian empires and ruins, classical Persian poetry that thrived in the first half of the second millennium of the common era, and what was considered to be ‘authentic folk culture,’ while largely downplaying Iran’s more recent history, especially its Islamic aspects. Moreover, as Haideh recounts in her memoir, the troupe’s reputation benefited from the support of the royal family, as well as the fact that the women were all from ‘good families,’ meaning elite urban women.

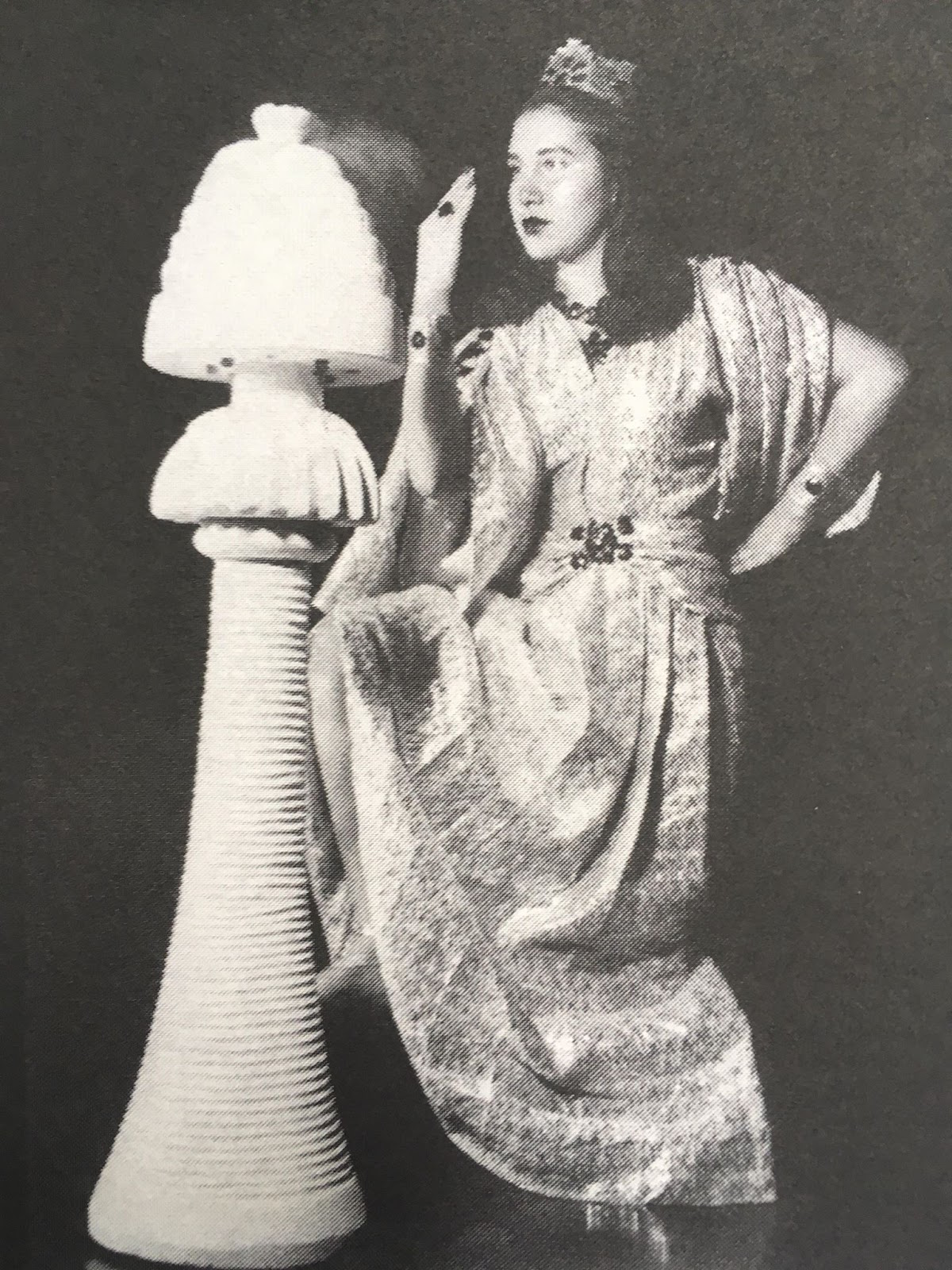

Tapping into Iran’s pre-Islamic past was done in various ways. The two grand empires of the Achaemenids (550-330 B.C.E.) and Sassanids (224 – 651 C.E.) in particular functioned as inspirational sources, which are both important in the shaping of modern Iranian identity. For instance, Nesta represented a Sassanid princess in the Dance of Love, for which her outfits were inspired by pottery-painting from that time. In another dance, Haideh portrayed a golden statue of an ancient goddess, for which inspiration was taken from the Greek Herodotus’ descriptions of the Achaemenid empire and from the friezes of Persepolis, the ruins of emperor Dariush’ palace near Shiraz.

Nila also turned to classical poetry as another source of inspiration. For example, multiple performances were based on stories from the national epic of Iran – the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), written in the tenth century by Ferdowsi – which consisted of numerous lyrical stories that glorified Persianate history. In one dance Haideh portrayed Gordafarid, a warrior woman from one of the stories of the Shahnameh. Furthermore, inspiration was taken from other famous Persian poets, such as the poetry of Hafez and Saadi and many dances were accompanied by recitation of their oeuvre.

In order to create a full “authentic” Persian experience, Nila turned her gaze towards landscape and villages. Outfits were rendered after folk attire and the colours of the outfits and decor were inspired by the colours of the desert. Inspiration for the choreography was taken from ceremonial dances of villages all over Iran: repetitive steps of these dances were combined with steps from modern ballet to create more dynamic choreographies.

By drawing inspiration from the aforementioned sources, the Studio for the Revival of the Classical Arts of Iran is a clear example of an invented tradition, rather than a restoration of dance as it claimed to be. Drenched in this ancient pride yet with a modern twist, their performances became something that was considered to be worthy to represent the nation. The troupe even went on to tour through the Middle East, Europe, and India to present Iranian culture.

Imagining “Modern” Gender

While it is curious that this tradition mostly sprouted from an American’s romanticised idea of Iran, it was eagerly accepted and embraced both by the members of the troupe and audiences. The following quote from Nesta’s memoir gives insight into this:

“Uncle Shahbahram attended the opening to see for himself just how much damage was being done to the family reputation, but to his surprise he found our performance deeply moving and serious of purpose, tapping as it did into the audience’s sense of pride in Iran’s past glories, its history, its literature, its music, yes, its dance.”

Nesta and Haideh, along with other dancers, contributed to the choreography by improvising and adding steps from their modern ballet education. There were several artists that brought their own craft to the troupe by designing costumes, devising music and telling stories to accompany the dances.

Another aspect that made the dance troupe a modern invention was the heterosociality of the performance. As mentioned previously, dance performances were usually a homosocial event in which men danced for men and women danced for women. Now, however, men and women danced alongside each other and even with each other, for an audience that consisted of men and women. Moreover, what was interesting was that women took the centre stage and men had a more subdued role; they did not flaunt their beauty and acrobatic skills as they had done in the past, and were instead relegated to supporting the female dancers.

Centering women did not go without resistance. Although some people perceived their performances as respectable and representative of Iran, there was still a lot of anxiety about women on stage. The families of the women especially were concerned about their daughters’ venture. While hundreds of men auditioned for the dance troupe, no women did, and all of them had to be persuaded by their dance teacher to join. Haideh’s family would initially not let her go on tour, while the family of Nesta was afraid she would damage their reputation.

This anxiety is palpable when we analyse the roles of the women in the dance performances. They mostly represented abstract tropes such as fire, a statue, a rose, or mythological women from the past such as Gordafarid, but not ‘real’ women. Although they were women dancers, their roles on stage de-emphasized their gender. They usually kept their distance from the men on stage. In one of the performances, however, Nesta danced intimately with a man in what she calls the Dance of Love, during which many people in the audience jeered. This shows that even though the dance troupe and its daring women dancers commanded respect through their representation of modern and ancient Iran, they still faced public disapproval, which highlights the tension between the heterosocial gender ideals promoted by the troupe and popular norms.

Nesta quit the dance troupe while they were touring Europe, and later emigrated to the U.S. The tour continued for two years, travelling through the Middle East and India. Afterwards, Nila stayed in Iran for a while before leaving. Later, in the 1950s, Haideh and her husband developed the Iranian National Ballet Company and the Iranian National and Folk Music, Song and Dance Ensemble, using similar methods of devising dance performances. A lot of internationally acclaimed ballet dancers and choreographers were involved in the process, but Haideh specifically stated that they owed a lot to Nila.

A video of the Iranian National Ballet Company in the 1970s

After the revolution in 1979, both ballet and folklore companies were disbanded and dancing (at least for women in public) was outlawed. Was the project then just a fleeting concoction of a wandering American orientalist? Although it did not succeed in weaving dance into the official tapestry of the nation of Iran, the project was influential or at least part of a bigger process of the embodiment of Iran’s new full fledged nationalism that pendulated between narratives of glorification of the pre-Islamic, the authentic Persian, and poetic pasts.

The personal stories of these dancers moreover highlight the gendered process of this attempt at nationalism. Dance thus became a site for embodied memory that was carefully selected and crafted. Although the ballet and folklore companies were disbanded, they spawned several offshoot companies in the Iranian diaspora where women continue to take center stage.

Nowruz celebrations in 2008 of Ballet Afsaneh, a company working in the tradition of the Iranian National Ballet Company and the Iranian National and Folk Music, Song and Dance Ensemble, based in San Francisco, California.

References:

Ahmadzadeh, Haideh. My Life as a Persian Ballerina. Morrisville, North Carolina: lulu.com: 2008.

Ramazani, Nesta. The Dance Of The Rose And The Nightingale. Syracuse, N.Y: Syracuse University Press, 2002.

Shay, Anthony. Choreophobia: Solo Improvised Dance in the Iranian World. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 1999.

Najmabadi, Afsaneh. Women With Mustaches and Men Without Beards. Berkeley, Calif: Univ. of California Press, 2010.

Meftahi, Ida. Gender and Dance in Modern Iran: Biopolitics on Stage. New York: Routledge, 2016.