The following is a guest post by Tannaz Sassooni. Born in Tehran to a Jewish family, Tannaz is a Los Angeles-based food writer interested in exploring the city’s global culinary landscape and interviewing moms and grandmas for a regional Iranian Jewish cookbook. Follow her on Instagram @tannazsassooni.

***

I grew up on the floor of my mother’s kitchen. I’d sit picking out seeds from a big metal tray of Omani black limes, shelling fava beans for baghali polo, or picking off the bitter buds from sprigs of basil for sabzi khordan, the plate of fresh herbs that accompanies every Persian meal.

In my Iranian Jewish home in Los Angeles, my mom cooked dinner every night of the week. Fluffy basmati rice, with its crisp, saffron-hued tahdig was ubiquitous. On Friday nights, we topped it with ladles of abgoosht-e gondi, the classic Shabbat dish of chicken soup with dumplings of ground poultry and chickpea flour.

On the best nights, we ate seconds and thirds of gondi kashi, a fragrant pilaf of basmati rice, beets, fava beans, ground meat, and fresh herbs, a recipe passed down to my mother by her own mother and mother-in-law, and known only among Jews from the city of Kashan.

At the time, I didn’t realize that what I tasted at home was just the tip of the iceberg of Iranian Jewish food.

Growing up in the US as an Iranian Jew is a little strange: people try to create some sort of winking kinship by mentioning what they consider to be “Jewish food,” like matzo ball soup or gefilte fish. But I never had matzo ball soup before my junior year of college and gefilte fish feels as foreign to me as a honeybaked ham.

What’s generally known as “Jewish food” in the US is really Ashkenazi food, reflecting the flavors of its Eastern European origins. I’ve always known that what I grew up eating was an entirely different cuisine omitted from the ranks of what Americans, including most Jews, consider Jewish food.

Even Jewish cookbooks that move beyond the Ashkenazi-dominant framework often overlook Iranian Jewish cuisine. When I received Claudia Roden’s The Book of Jewish Food as a gift some years ago, I was struck by her commitment to non-Ashkenazi foods: the majority of the book consists of recipes from Turkey, Syria, Spain and elsewhere, with the name of each dish in its native language. The cookbook is a joy to get lost in.

Yet, there are only a handful of Iranian recipes included, and of those, several aren’t specifically Jewish dishes at all. I knew from my family meals that there was so much to Iranian Jewish cuisine, and decided to learn as much as I could.

As I set out to understand Iranian Jewish cuisine, I couldn’t really turn to Jewish cookbooks: Iranian food is largely absent from them. At the same time, Persian cookbooks tend to ignore the contributions of the Iranian Jewish community, which today numbers around 300,000 people worldwide.

Although Iranian Jews eat many of the same dishes as their Muslim, Christian, Zoroastrian, and Bahai neighbors, there are also dozens of dishes that are particular to the Jewish community that reflect their unique historical, cultural, and geographic circumstances. And yet, there’s never been a collection devoted solely to Iranian Jewish food, one that comes from within the community.

I decided to take matters into my own hands. I began interviewing Jewish women from different cities in Iran. What foods did they make for holidays? What was their Sabbath meal? How did they break the Yom Kippur fast? What dishes were served at weddings, memorials, and births? What recipes did they share with their non-Jewish neighbors, and which did they make differently?

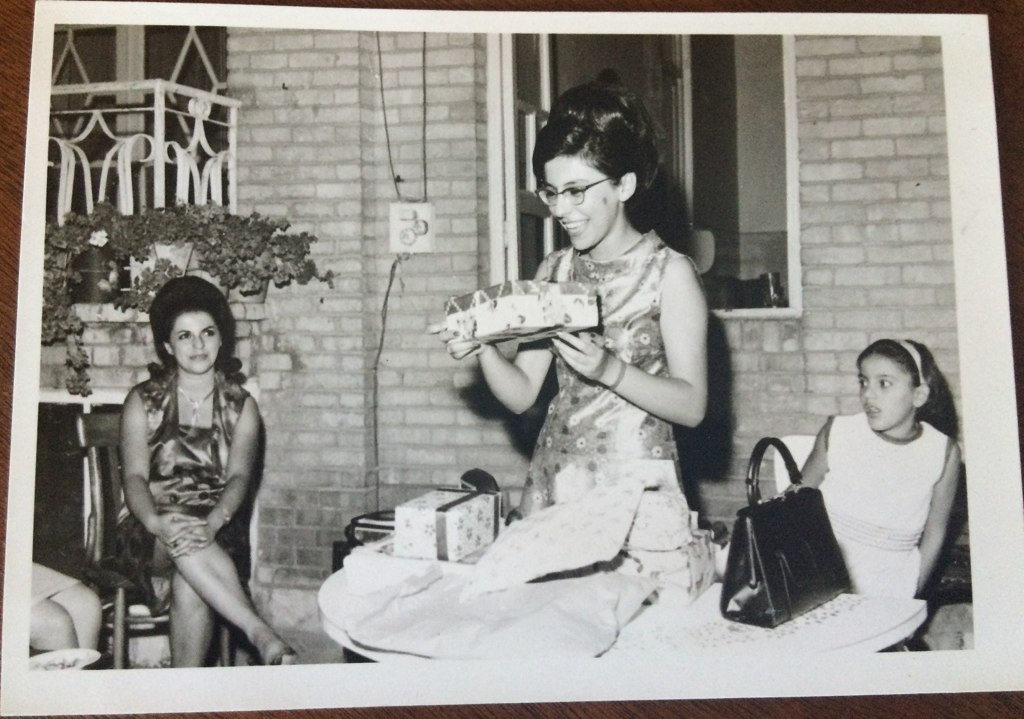

What unfolded was years of spending time with Jewish people from Iran – usually women, usually elderly. My own understanding of both Iranian and Jewish food expanded. Like the gondi kashi that was my favorite dish my mother made, there were countless regional specialties I’d never heard of. All of them had different variations; much like religious and cultural practices, recipes were context-dependent.

When I visited the home of a Shirazi woman in Los Angeles named Homa, her parrot greeted me, squawking in a mix of English, Persian, and Hebrew. It was from Homa that I learned about khalebibi, Iran’s version of the Sabbath pot. Due to religious restrictions on handling fire – it’s considered “work” during the Sabbath day of rest – many Jewish cultures around the world have some kind of overnight pot: a dish that you set to cook on Friday afternoon, then eat for lunch on Saturday. Though specific recipes vary, the Shirazi khalebibi is a rice dish slow-simmered with some combination of turnips, lentils, kidney beans or black eyed peas, beef, cabbage, and kohlrabi.

I try to paint a definitive picture, but the reality of the ebb and flow of cuisine across regions, and even across borders, is not so fixed. My eldest aunt, Mohtaram, also made what she called khalebibi, but when I asked her about the ingredients, it was clear that what she was actually making was the Baghdadi Jewish Sabbath pot, t’beet, a whole chicken cooked with rice in a spiced tomato base.

Auntie Mohtaram’s husband was from Kermanshah, a city directly connected by a trade route with Baghdad, and his two brothers had married Baghdadi Jewish women. So, like many Iranian Jews in border towns near Iraq, her cooking was heavily influenced by Iraqi Jewish cuisine.

Frequently, I’d see the Jews of a specific region assigning religious use to local specialties shared by their non-Jewish neighbors. Shavuot is an interesting example of this. Shavuot commemorates the revelation of the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai. It’s traditional to eat dairy foods – cheese-filled blintzes are a common Ashkenazi favorite – and much of Iran makes shir berenj, rice pudding, for the holiday. But in Kermanshah and Sanandaj, two primarily Kurdish cities, Jews favor shelkineh, a Kurdish crepe-like bread fried in the fragrant local butter and served sprinkled with powdered sugar.

Even the beloved chelo abgoosht-e gondi, the chicken soup served over rice which I’d believed to be ubiquitous at Iranian Shabbat dinners, was called into question.

Any conversation about Iranian Jewish food starts with gondi, tender chickpea flour and ground poultry dumplings seasoned with cardamom and simmered with chicken pieces in a soup that’s served over steamed basmati rice, with crisp golden tahdig. The comforting fragrance of this dish marks the end of the week for Jews in Iran and throughout the Iranian diaspora.

But in Sanandaj, they don’t have gondi at all. Their most popular Shabbat dinner meal is koofteh berenji – large balls made of meat and rice, stuffed with a date or a bit of ground dried lime in the center and simmered in chicken broth. From a jeweler in Chicago, I learned that in Mashhad, where the Jewish community historically practiced their faith clandestinely following a 19th century riot, the Shabbat dinner meal is a dish called chelo nokhod ab, a soup of legumes, fresh herbs, and potato and ground beef meatballs known as gondi Mashhadi. In every corner of Iran, Jewish Iranians developed different traditions that spoke to their local histories, cultures, and flavors.

Seasonality was ever-present in the stories I’d learn from these women. A Tehrani woman recalled the queue of camels that would line her street, laden with beets, watermelons, turnips, and other produce, which her father would buy at the end of summer to carry the household through the winter. My own aunt told me about the “lime juice ceremony” in her childhood home in Tehran at the same time of year. The whole family would get together to sterilize jars and squeeze mountains of limes to preserve in the basement for use throughout the year.

My mother recalls that in her parents’ summer house, on the days they’d get fresh warm bread from the local baker, the kids would pick tomatoes, parsley, mint, and cucumber from the garden and make a salad to have with the bread and some salty cheese for a perfect snack.

One Shirazi woman described a cold soup of finely diced tomato, cucumber, onion, and mint in a watery lime juice and brown sugar base that her family would eat on Shabbat eve in the summer. To me it sounds like a dairy-free alternative to ab doogh khiar, a refreshing cold yogurt soup eaten by all Iranians, adapted to allow it to be eaten with meat according to Jewish dietary laws.

It’s easy to wax nostalgic about an idyllic distant past, but in reality, being a woman in traditional Iranian Jewish households meant immeasurable unsung labor, and sometimes even suffering. My Auntie Mohtaram recalled a night early on in her marriage. Married off at around sixteen years old to a man twice her age, she’d moved to her in-laws’ home about 600 miles from her parents. The family had gone on a day trip, and she was in charge of preparing dinner for them for their return. She was a teenager, and hadn’t cooked much; she hadn’t yet developed a knack for it. And now she was away from home, with the pressure of impressing her in-laws.

So, she toiled in the kitchen: plucking stray feathers from a chicken bought from the town’s kosher butcher, skimming smelly scum from the surface of the broth as the chicken boiled, and forming gondi, dumplings of ground meat and chickpea flour, in her hands, one by one. All the while, she fought off nausea: teenage Mohtaram was pregnant with her first child. She cried as she told me this story over a half century later.

But not every woman’s story fits the traditional model. One woman I spoke with left Iran in the 1970s to get her master’s degree in electrical engineering in Northern California. She never married or had children, but rather followed her academic pursuits, getting her PhD, working as a professor and engineer until she retired. Her father was an atheist, and instead of idyllic family holiday celebrations, she recalled her mother quietly fasting for Yom Kippur while her father opted out.

Nevertheless, she shared with me the cookbook that her late mother made while her father was ill. Filled with kitchen wisdom and family recipes like ash-e torshi, a sour hearty soup, and khoresht-e kangar, a stew of meat, fresh herbs, and artichoke, the cookbook was an invaluable heirloom that connected her to her mother and father. “Cherish your parents,” she told me.

When revolution rocked the lives of Iran’s Jewish community, forcing tens of thousands to leave the country, women provided a sense of normalcy for their families by carrying on their traditions in a new setting. Through these dishes, they rebuilt homes elsewhere.

My mother left Iran in early 1979 along with my sister and me. We lived with my grandma for the first three years before my dad finally made his way to Los Angeles. As we made our way here, getting the family together with the language, cuisine, traditions, and conviviality of the old country created rare moments of comfort in uncertain times in an unfamiliar place.

In the days before Passover, my father still pulls out a hand-crank meat grinder and his late father’s handwritten haroset recipe, then sets to work on this complex mortar of nuts, dried and fresh fruits, spices, and wine.

I’ve seen young Iranian Jews who were born in the US post artful photos on Instagram of this same collection of ingredients as they prepare for their seders in Los Angeles and New York. It’s heartwarming to see this tradition persevere, and adapt – they make theirs with a food processor – from generation to generation.

In recent years, we convinced my mother not to bother with an elaborate Persian meal to break the Yom Kippur fast and have opted for a bagel spread instead. Just as trade patterns and migration brought international influence to the cuisine of Jews in Iran, here in the US, we’re not impervious to the influence of our neighbors.

Nevertheless, the meal still begins with the three crucial items that many Iranian Jews have used to break the fast for generations: a cup of fragrant black Persian chai, a soft-boiled egg, and a cup of faloudeh sib – a reviving mix of shredded apples in a lightly sweetened rose water syrup, served over ice.

As my mom stood in the kitchen with her young daughter at her feet, cooking her way through uncertainty, I don’t think either of us could have imagined how different my life would be from hers, and from the lives of her mother and sisters before her.

Like most Iranian Jews, we’ve never returned to Iran since leaving amid the chaos of the Revolution nearly half a century ago; doing so under the Islamic Republic is just too risky. Although a small number of Jews continue to live in Iran, we are primarily a community in functional exile.

The culinary legacy that our matriarchs left for us is so rich, and if we do not document it, this heritage will be lost. My mom lost her mother almost 30 years ago; Auntie Mohtaram died in 2020. Our family now includes great-grandchildren and even great-great-grandchildren, each generation farther from the traditions of a distant “home.”

But as our understanding of home as our parents knew it fades, home becomes something new: not a geographical location, but something in us.

Home is the recipes we continue to make, the gatherings we have with our families, the dances we dance and the songs we sing together. The values we share – hospitality, family, tradition – our shared language, with all its sweet poetry: these are our home.