The following piece was written by Parham Ghalamdar, an Iranian-born painter who completed his MA in Painting at the Manchester School of Art. His artistic endeavors explore themes encompassing the climate crisis, mythology, and accelerationism.

***

In October 2020, I found myself irresistibly drawn into the depths of “Catching Your Feeling,” a sprawling painting by Iranian-American artist Nicky Nodjoumi (née Nikzad Nodjoumi) drenched in impassioned alla prima brushwork. I stared at the swathes of lamp black surging like waves of molten petroleum, wrapping the canvas in a shroud of mystery. Wrestler figures, their contours bending and warping, were swallowed by the boundless ambiance, dissolving into the inky abyss.

The glossy, pitch-dark expanses shimmered and danced, transforming my observation into a spectral journey. I could feel the tension, both metaphorical and actual, resonating from the fervent strokes. An eerie echo of Reza Negarestani’s horror novel “Cyclonopedia” whispered tales of oil demons, making the experience all the more haunting. I couldn’t help but ponder the passage of time since the 1979 Iranian revolution. Time might have sailed forth, but the heartbeats of the struggle remained just as fervent. It was as though Iranians were ensnared in an eternal waltz, their dance mirroring the stark dichotomies of light and shadow, poignantly frozen on Nicky’s canvas.

Nicky Nodjoumi is a path-breaking artist whose journey offers a blueprint for understanding the complex forces of global politics over the last four decades. His profound figurative painting resists the idealism and passiveness of abstract painting. To truly appreciate the depth of his impact, this piece draws inspiration from a phone conversation I had the privilege of sharing with the artist on December 10, 2020. What unfolds here are interpretations and expansions on our engrossing exchange, aiming to frame Nodjoumi’s journey and its relation to contemporary Iranian history.

The Revolutionary Nicky

Nicky Nodjoumi earned his Fine Arts degrees in Tehran in 1961 and New York in 1974. While studying, he collaborated with the Confederation of Iranian Students National Union, creating political posters opposing the Iranian monarchy and the Vietnam War. One of the posters he made during this period was lauded by the New York Times as one of the most influential works of American protest art in the 20th century. In 1975, upon returning to Iran, he faced intense scrutiny from the Pahlavi regime’s notorious intelligence agency, the SAVAK, enduring three months of harsh interrogations and being banned from academic pursuits. Despite these challenges, he continued visiting Iran, bringing his artistic skills into the rising revolutionary fervour.

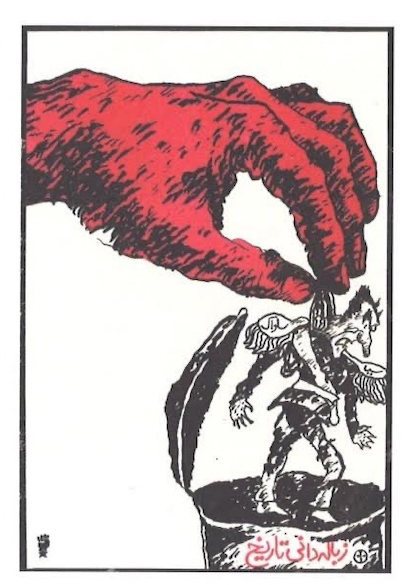

Nicky was a part of the “Group of 57” (گروه 57), an assembly of art students that took over the “Judgment Salon” (سالن ژوژمان) at the Tehran University of Art. They leveraged the university’s safe status from military incursions to create a hub for artistic and revolutionary creativity. This occurred mere months before the momentous February 1979 fall of the Shah. The group was an amalgamation of left-wing artists and students and was inspired in part by the protest posters of The École des Beaux-Arts during France’s 1968 upheavals, according to Nicky. Among the group were luminaries like Morteza Momayez, Arapeek Baghdasarian, and Mostafa Ramzani, who would ascend as some of the defining artists of their generation. These posters bore a distinctive star and fist logo, with Fig.2 showcasing an illustration by Nicky Nodjoumi himself.

Nicky shared that soon after the revolution’s triumph, he was offered a solo exhibition at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. The events surrounding this show, infused with drama, were captured in the recent HBO documentary, “A Revolution on Canvas (Untitled Nicky Nodjoumi),” directed by Sara Nodjoumi and Till Schauder. The film delves into the mysterious vanishing of over 100 artworks by Nicky Nodjoumi.

Told through the lens of Nicky and his wife Nahid Haghighat, the story, shrouded in intrigue and secrecy, takes viewers on a mesmerizing journey of art and mystery. As we anticipate the film’s online release, the vivid account Nicky shared with me offers some crucial insight into how the drama unfolded.

The incident occurred in August 1980. The then-head of the museum asked him to showcase about 120 paintings, created pre-1979 revolution, depicting tormented and bound figures being wrapped up and tortured and interrogated. He also displayed a series entitled “A Report on the Revolution,” featuring ten large oil paintings. The exhibition, however, only lasted two days.

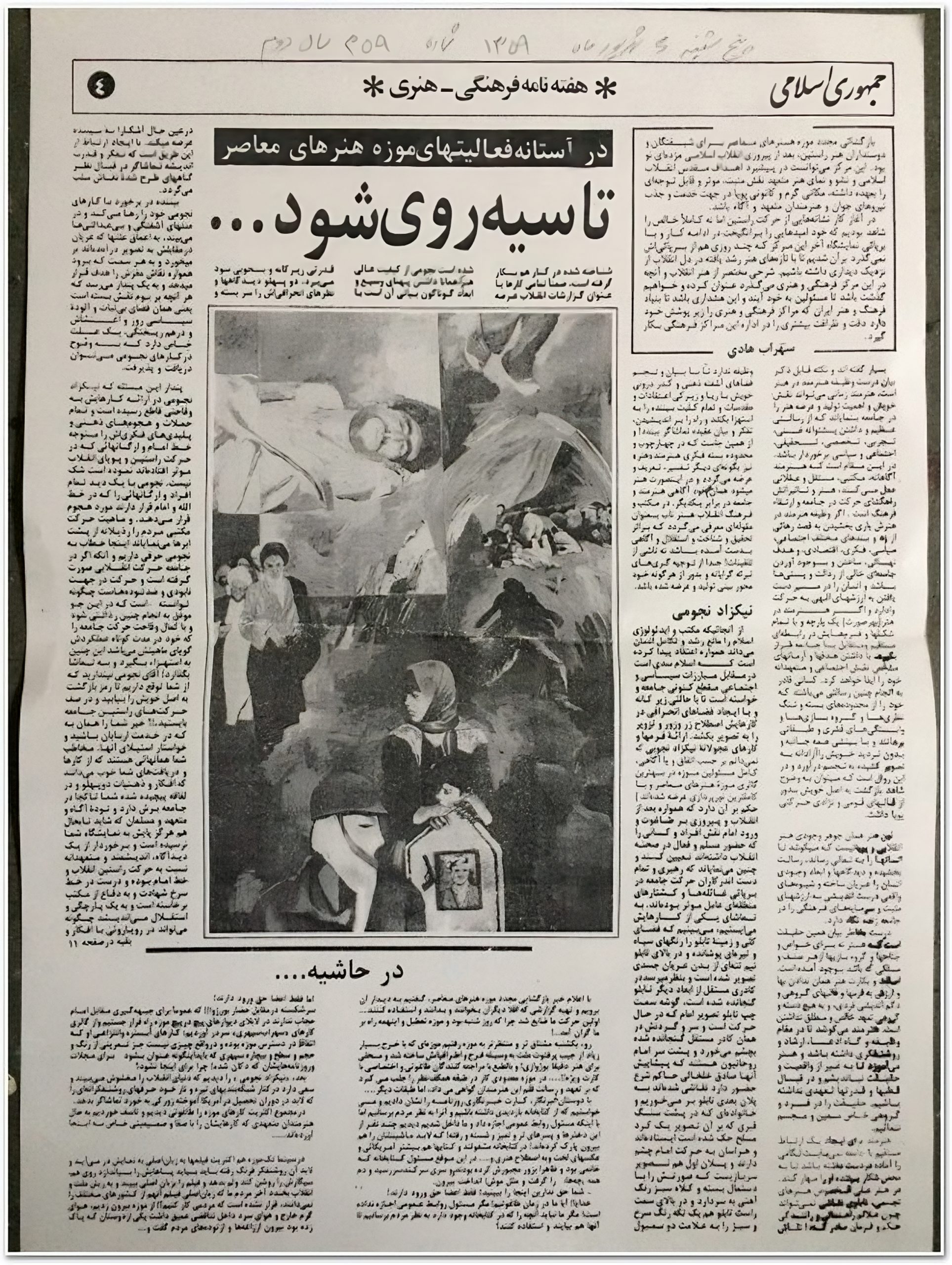

Within a day of the exhibition’s opening, a scathing critique graced the pages of Islamic Republic newspaper. The review included a torrent of accusations against Nicky, melding Islamist rhetoric with Soviet Socialist Realist jargon. Nodjoumi was rebuked for “targeting those faithful to Allah and the Imam’s teachings with his one-dimensional viewpoint,” and portraying “Islamism as a stumbling block to human progress.”

Yet a humorous nuance surfaced in the article’s begrudging nod to Nicky’s artistry: the readers were cautioned of the paintings’ captivating technique and compelling narrative, suggesting they could find themselves “losing themselves” within the depicted tales. Nicky’s work was dangerous because it was so good, apparently. Nicky recalled this segment with infectious laughter, emphasizing the irony with evident amusement.

Were the article’s repercussions purely abstract, it might have been shrugged off. The consequences, however, were grave. This former revolutionary was stigmatized as a traitor. He was targeted by the Islamic Revolution Committees, an organization in the midst of evolving from revolutionary zealots into a policing force. A menacing call to the museum on Thursday night prefaced the harrowing events of Friday, when militants descended upon the venue and attempted to take the works down.

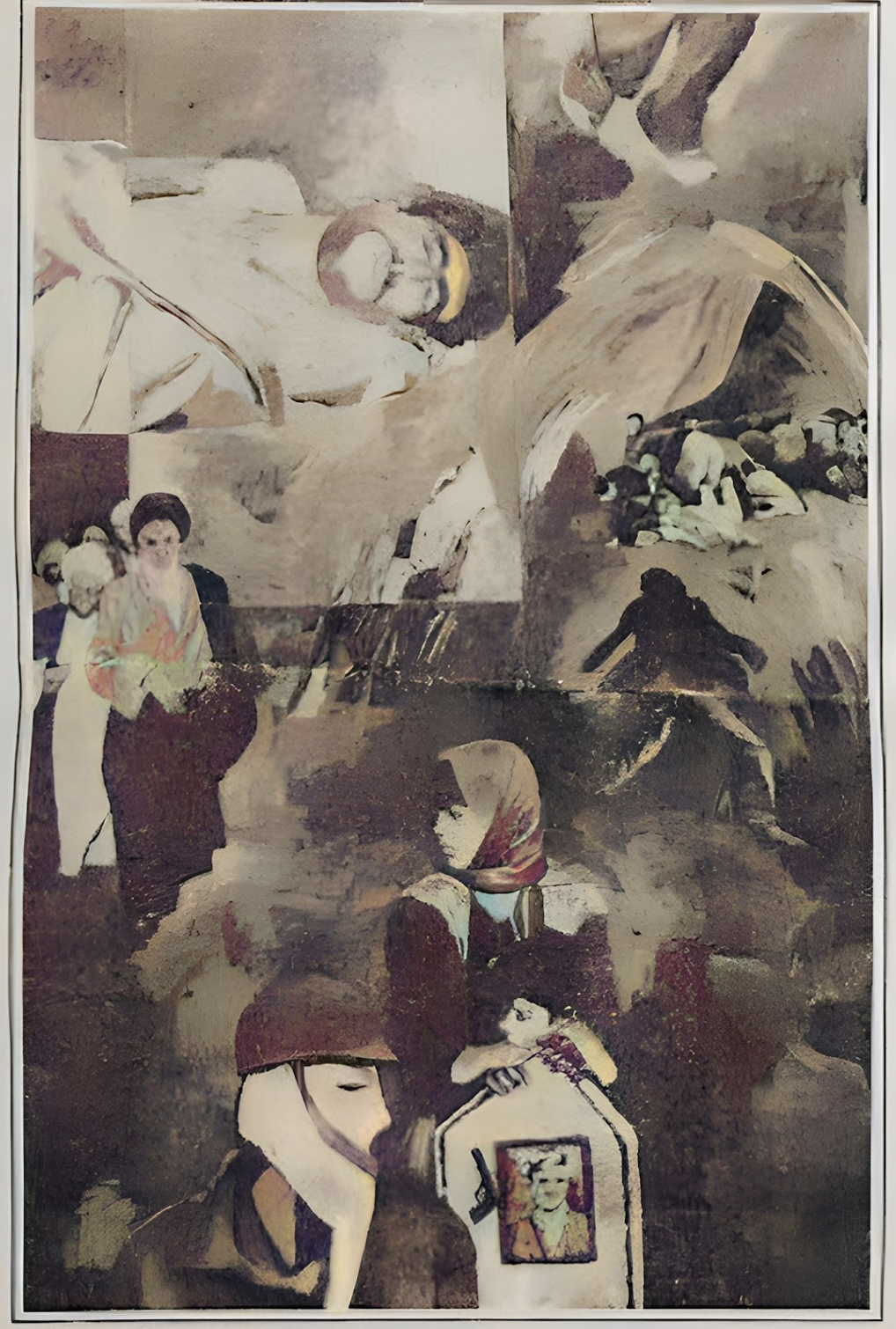

In a bid to defuse tensions, the museum hastily withdrew one contentious piece that had been attacked in the newspaper. This piece (Fig 3.1), interspersed with depictions of figures like Ayatollah Khomeini and the notorious “Hanging Judge” Khalkhali, underscored scenes of violence and grief. It notably indicted Khomeini for his role in the 1979-81 massacres in Kurdistan. The show’s timing was particularly poignant, aligning with the anniversary of his order to repress the Kurdish rebellion on August 18, 1979.

On Monday, Nodjoumi was summoned to the museum and told that the militants were flipping his paintings featuring images of religious clerics to face the wall instead of visitors. The museum’s higher-ups sought a statement from him proclaiming the exhibition’s alignment with the revolution’s democratic spirit. He gave one, but it did not save him. On the counsel of a fellow artist, Nodjoumi left the country within a week, leaving behind his cherished artworks at the museum. Tragically, they were never returned to him.

After 1980

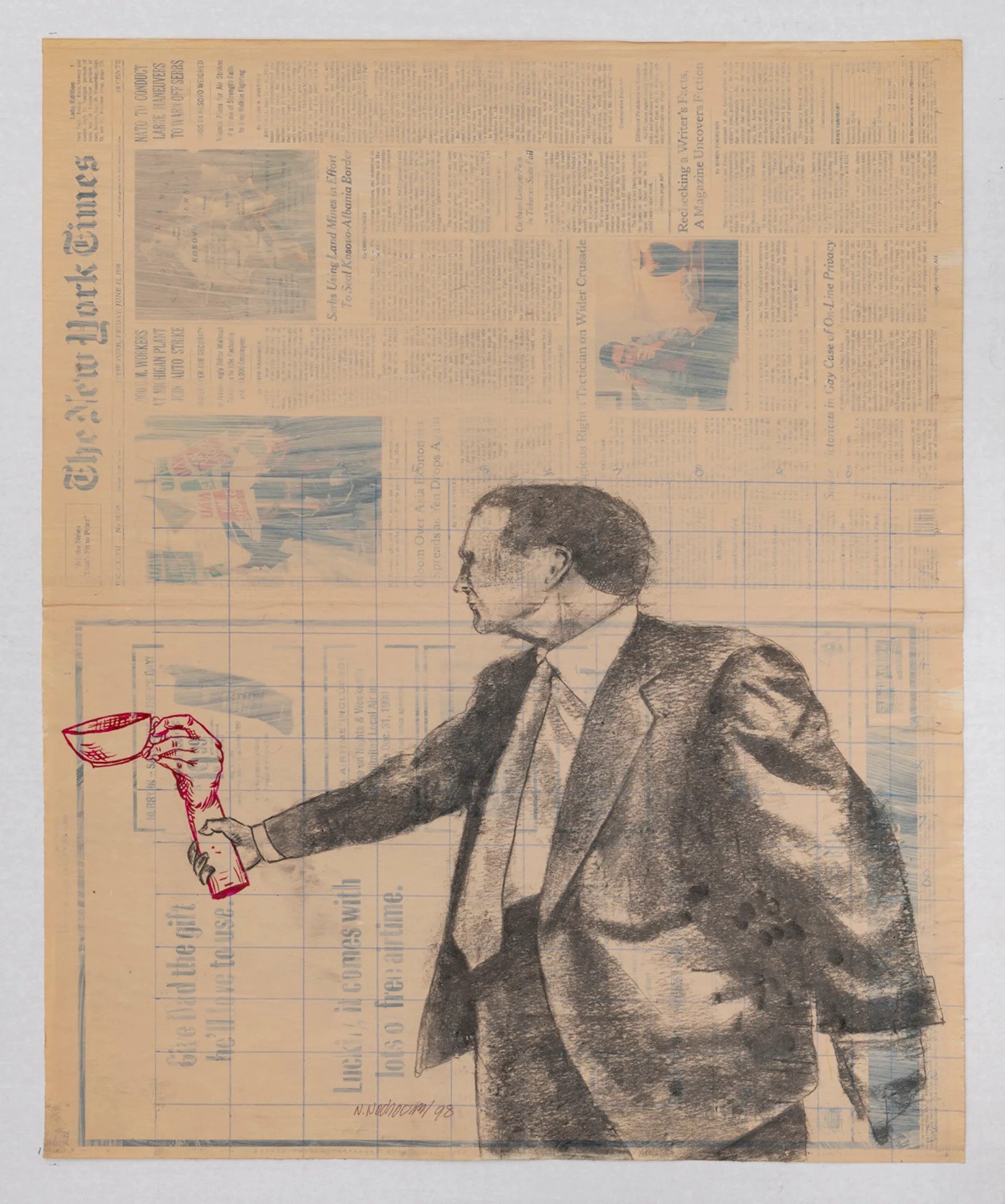

Nicky departed from Iran. But his artistic journey flourished. He recently held two solo exhibitions: “The New York Times Drawings 1996 – 1998” and “Reawakening 1995.” These exhibitions are a bridge between his 1979 phase and the present. His pieces remain mostly figurative, painted with raw, swift techniques, evoking the urgency of a graffiti artist on the run. The marks look confident. While the backdrop of his paintings grew more abstract, they consistently contain representational elements, such as powerful suited men stepping into turmoil and fragile botanical illustrations. His penchant for caricature remains evident, a natural extension of his habit of reading newspapers and then painting over them or using cutouts as artistic inspirations.

Nodjoumi’s art and activism serve as defenses against oppression, echoing the democratic spirit of the revolution. Drawing from Walter Benjamin’s “The Storyteller,” Nodjoumi’s paintings can be seen not just as stories but as records of political history and warnings against rising authoritarian figures, whether Pahlavi, Khomeini, or new right-wing movements in the West. Additionally, Nicky’s art intertwines with Iranian mythology. Dr. Bahram Beyzai’s lectures at Stanford explore Iranian myths’ relation to life, growth and wisdom. Nodjoumi’s depiction of plants reflects these themes, emphasizing the fragility of our existence.

The Absurdist Nicky

In 2020, he held a solo exhibition in London named “Singing a New Song.” While visiting, I was completely enveloped by the magnificence of Nodjoumi’s oil masterpiece, “Approaching Masked Carnival.” The sheer scale and intensity of the artwork conjured feelings akin to facing a wild predator in its natural habitat. The 1980 newspaper article had been accurate in cautioning viewers about the immersive power of Nicky’s creations – decades later, the maestro’s talent remains undiminished. The newspaper’s grayscale depiction of the artwork paled in comparison to the tangible experience.

This massive work presents a dramatic and vibrant depiction of a bizarre scene at a stormy forest’s edge, inhabited by distorted suit-clad petro-masonic men engaged in seemingly nonsensical activities as if they are theorizing their conspiracies. One character, sporting a chicken mask, performs an eerie magic trick with a chair, lending an aura of absurdity and ritual. The figures, with mismatched bodies and legs, appear to glitch into the scene.

The absurd is a condition where humans exist in an irrational, meaningless universe, with life having no purpose beyond its mere existence. The search for meaning in such a world inevitably plunges the seeker into deeper conflict with their surroundings. This realm of ceaseless struggle to make sense amidst burgeoning insanity could be where Nodjoumi’s painting resides. His artwork can be viewed as a visual commentary striving to articulate the illogical political and social situations he has witnessed between Tehran and New York. It’s no surprise that Nodjoumi often opts to paint his backgrounds with coarse, grungy strokes, hinting at a harsh concrete wall or a foreboding sky.

Unlike the enticing illusion meticulously constructed in Renaissance paintings, Nodjoumi’s artwork blocks your way. His paintings act as warning shots, refusing to invite you into a cozy, orchestrated carnival. Instead, they depict an irrational, absurd mob teetering on the brink of havoc at any moment. Nodjoumi’s painting is an intriguing fusion of serenity and chaos. His figures are shown performing magic tricks against the backdrop of an impending tornado, a scene that could grace the cover of Mark Fisher’s “Capitalist Realism,” hinting at a nihilistic sense of humor.

The artwork satirizes men dressed similarly to politicians and bankers, suggesting figures of power. The incongruity between their authoritative appearance and their participation in superstitious activities suggests the superficiality of men in suits. Despite its dark, absurd humor, Nodjoumi’s work is neither meaningless nor passive.

In “The Absurd in Literature,” Neil Cornwell differentiates between nonsense and the absurd, arguing that pointlessness is essentially non-serious in the realm of nonsense, whereas in the absurd context, it is deeply serious. The absurd doesn’t denote meaningless resignation or disconnection from reality; it’s a reasonable stance when confronted with the unalterable reality of mortality. Yet, acknowledging mortality also entails the responsibility to uphold life, morphing into a call to action. Nicky employs hurried, grungy brushstrokes and paint dribbles at the bottom of his artworks as stylistic tactics to underscore the urgency and significance of this call. Nodjoumi’s strategy to counter the surrounding irrationality involves proactive engagement, not surrender.

Nodjoumi’s steadfast devotion to painting amidst the most daunting circumstances acts as a rebellion against prevailing irrationality. This unyielding resolve suggests that the artist sees painting as a medium to interact with life, without necessarily subscribing to its terms.

He remains unwaveringly devoted to the democratic socialist ideals of the 1979 revolution. Indeed, his tenacity aligns perfectly with Brecht’s notion that ‘you can’t write poems about trees when the woods are full of policemen.’

Author’s Note: This article was originally penned in early 2023. It has come to my attention that since that time, Nicky Nodjoumi has posted several caricatures on his personal Instagram that are in my view Islamophobic and homophobic. As the author of this article, and as someone who identifies as queer, I want to make clear that I condemn all forms of prejudice and hate speech. I believe this article is important because Nicky Nodjoumi’s work and life story are important for understanding the history of art in modern Iran, and I hope that Nicky Nodjoumi will delete these caricatures and address these errors of judgment publicly.