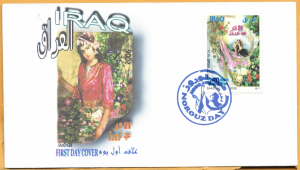

A mama bird feeding her hungry hatchlings. A sea of wildflowers in the mountains of Iraq. An open field with Tajik performers playing music and walking on stilts. What do all these images have in common? They’re all stamps celebrating Nowruz!

From a Nowruz stamp issued by Iran in 1964 featuring a branch of a cherry blossom tree to the USSR’s “Folk Festivals” series in 1991, Nowruz stamps have become an iconic favorite for those sending Spring greetings across the region. Nowruz is celebrated from South Asia to the Balkans and the stamps below reflect some of that geographic diversity.

Far from monolithic, Nowruz designs have evolved over time and change depending on the country. The USSR tended to display crowds of smiling people outdoors, reflecting holiday traditions in Central Asia.

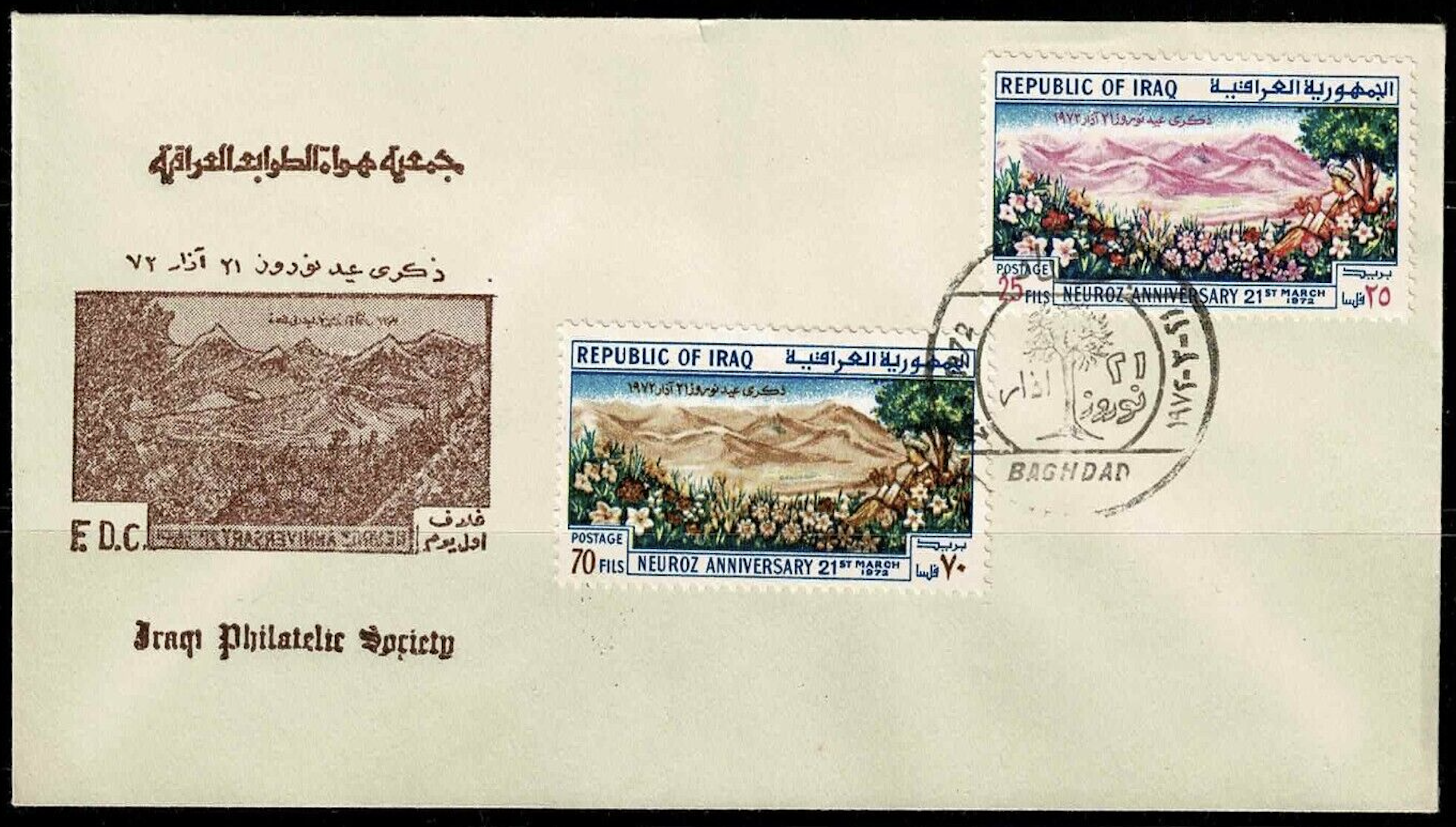

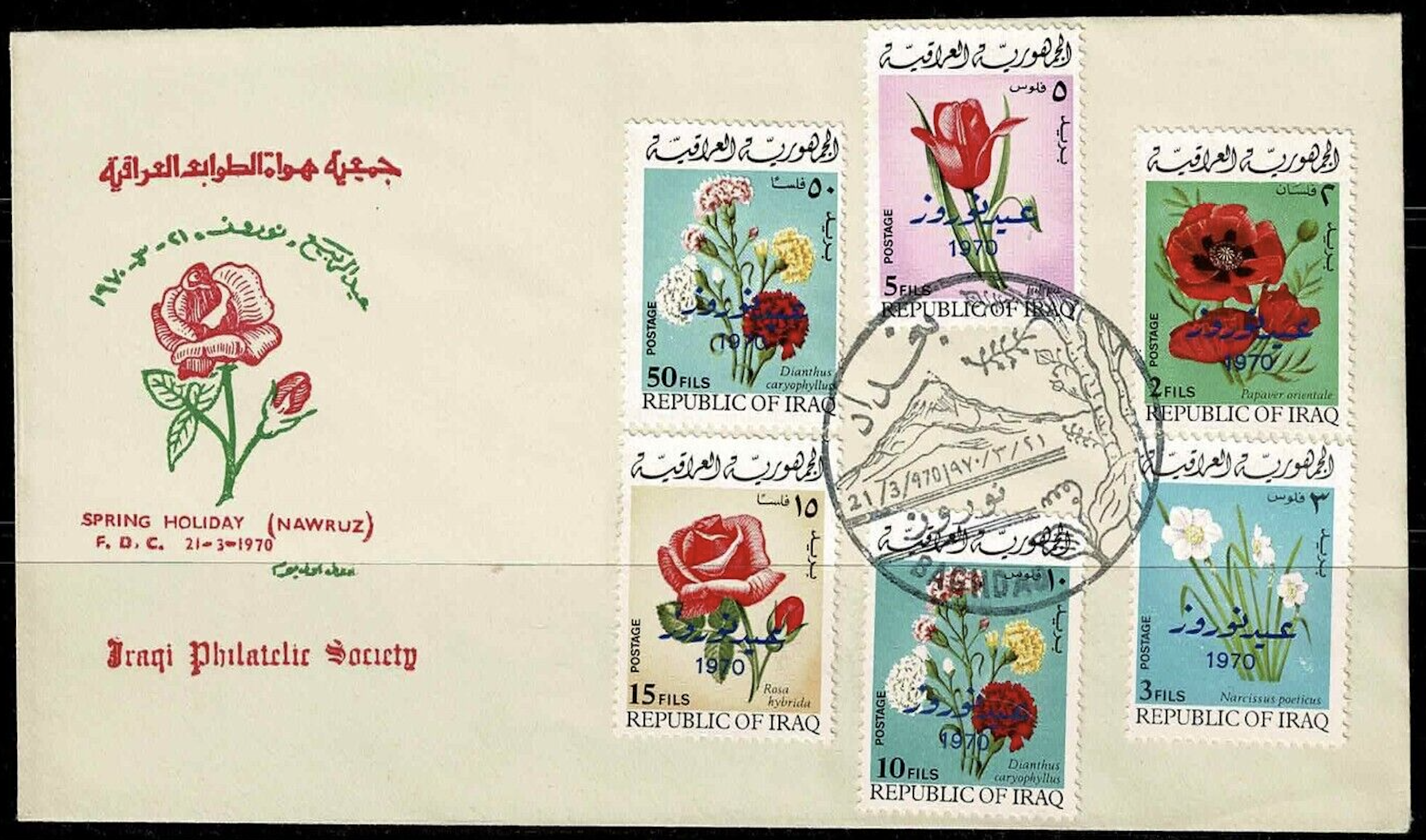

Those from Iraq, meanwhile, presented wildflowers, the Zagros Mountains, and Kurdish dress, reflecting the holiday’s association with Kurdish communities. As a result of Saddam Hussein’s war on Kurdish culture, Nowruz stamps disappeared from the country’s postage in the mid 1970s until their return in the early 2000s following the US invasion.

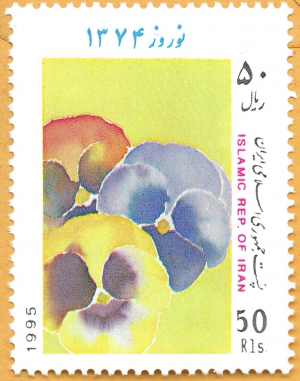

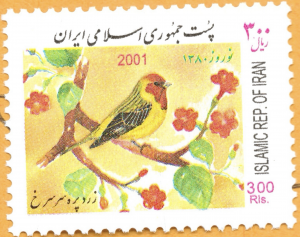

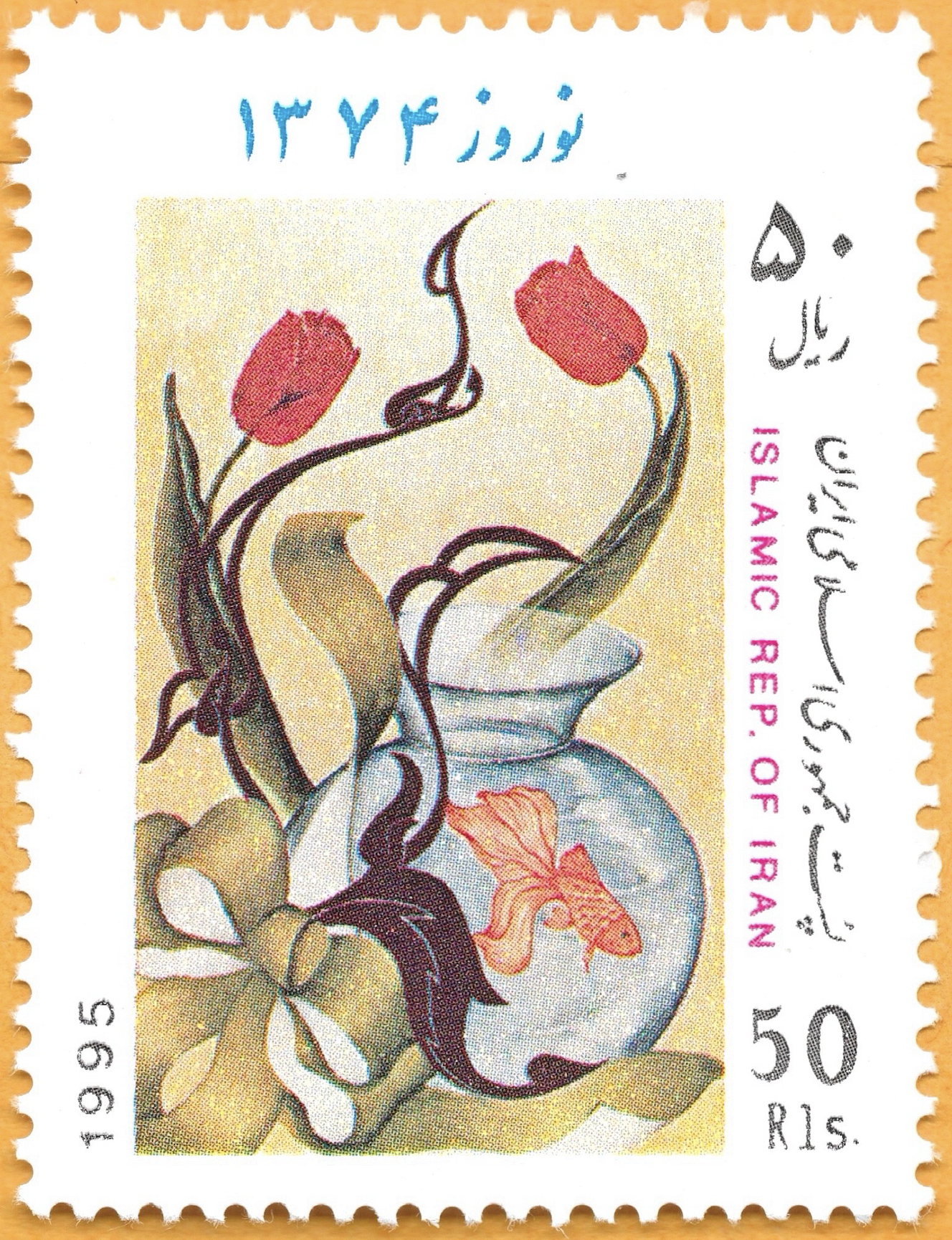

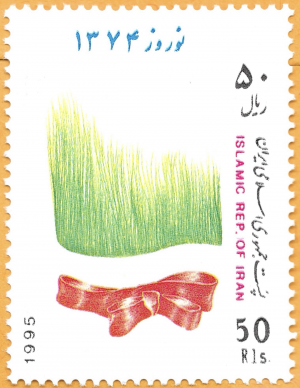

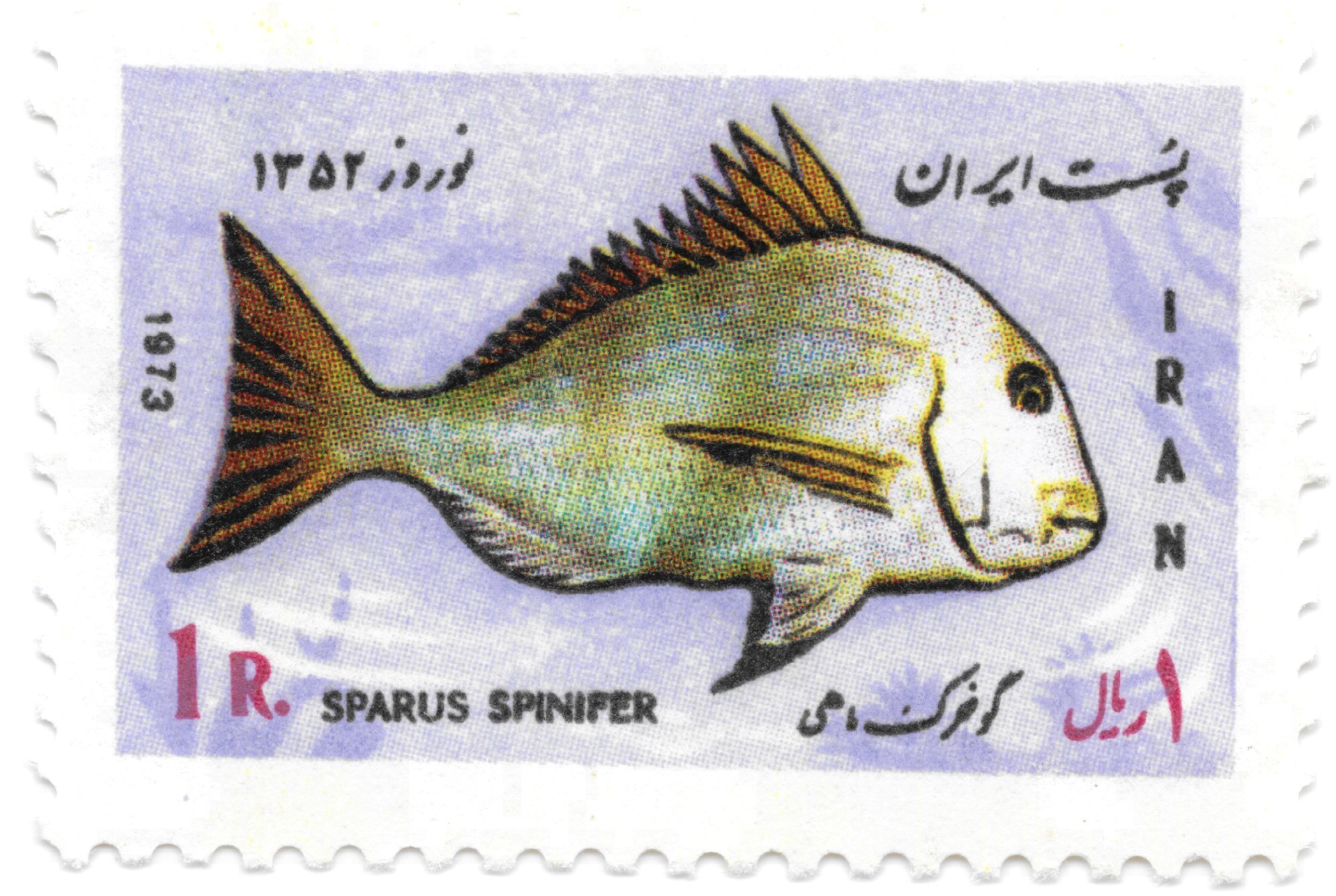

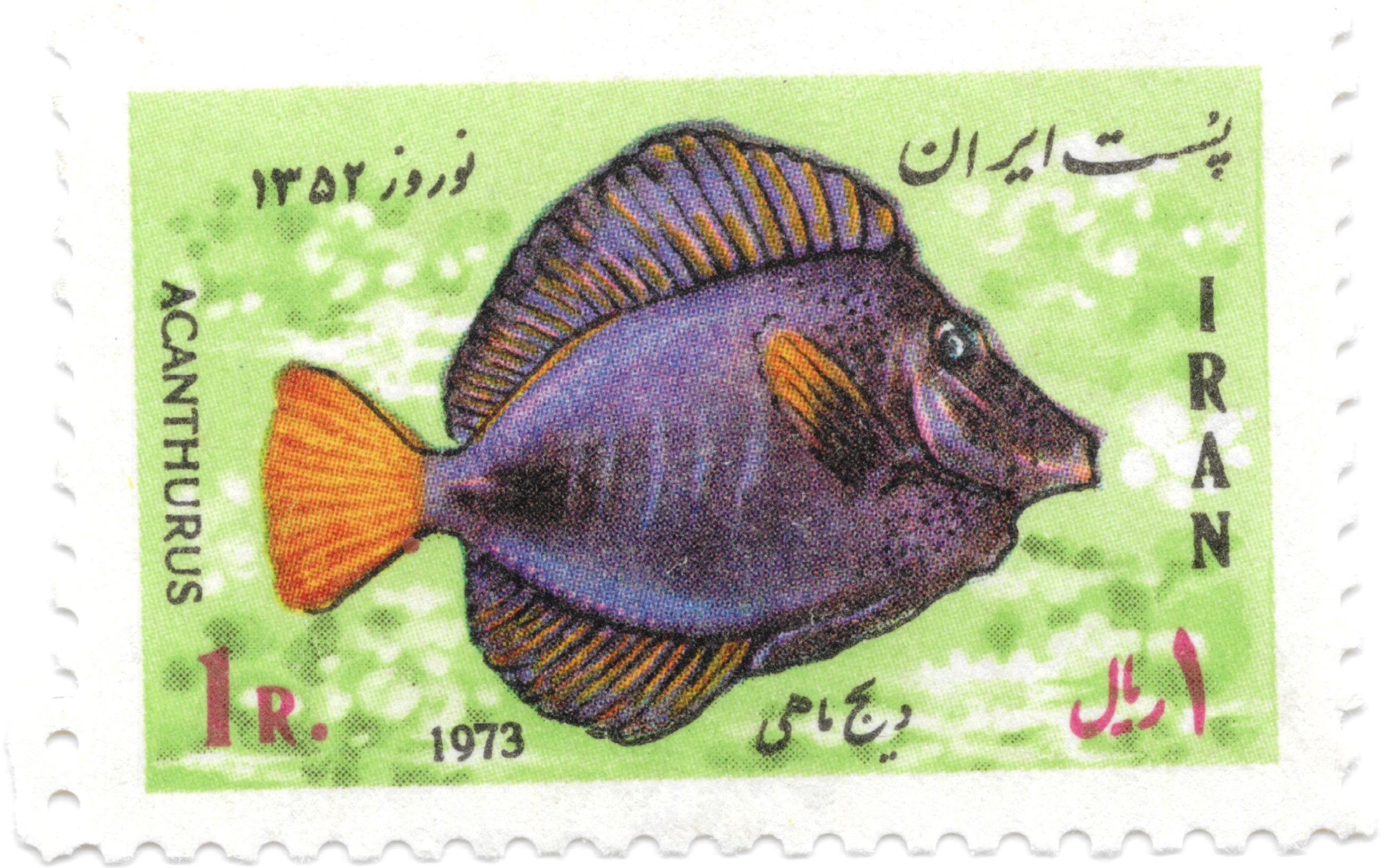

However, Iran has issued more stamps celebrating the arrival of spring than any other country, reflecting the holiday’s central place in Iranian national identity. Iranian designs often depict natural elements like birds, flowers, and decorative eggs. But they also feature disparate symbols like ancient ruins, candles, poetry, and desserts.

The flowers and birds were chosen for their symbolic associations in Iranian culture. The flower laleh vajgoon (the inverted tulip) is regularly depicted because it blooms at the highest elevations of the Alborz and Zagros mountains in early spring and features prominently in the legend of Siavash, a legendary prince seen as a paragon of bravery, talent and innocence. The inverted tulip is said to have bowed its head in sadness after witnessing his death in the Iranian epic poem, the Shahnameh.

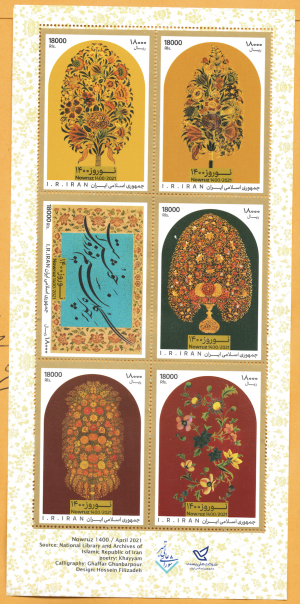

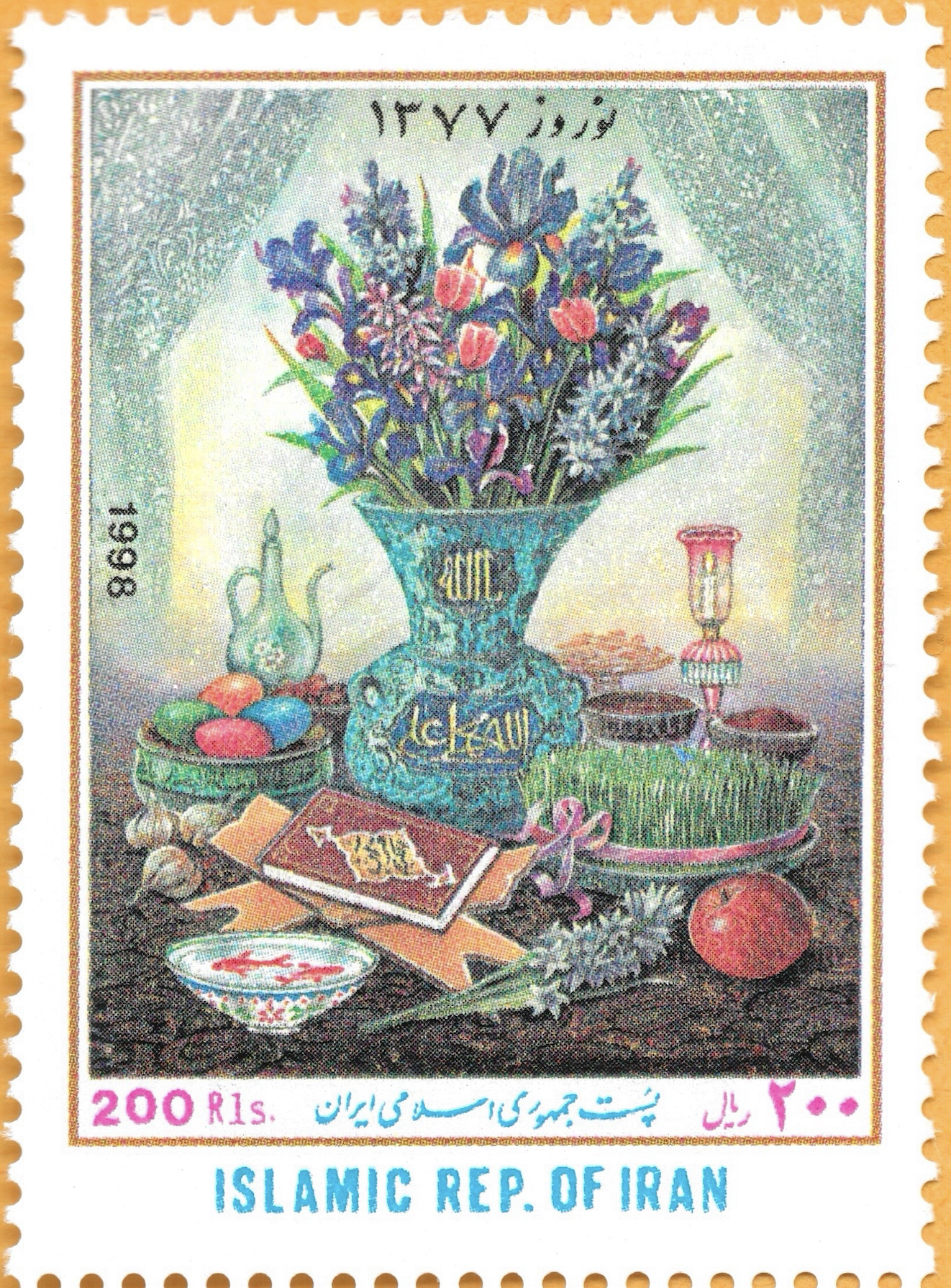

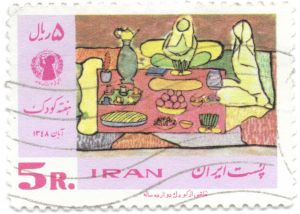

Since the 1960s, the sofreh haft seen has appeared on Iranian stamps every few years with the seven elements (literally, Seven S’s) of the traditional Nowruz spread set up in Iranian homes. The haft seen has been represented through children’s drawings, classical paintings, and anatomical illustrations explaining everything to be included–sabzeh (grass, for rebirth), senjed (dried fruit, for love) sib (apple, for beauty and health), seer (garlic, for health), samanu (for wealth and fertility), serkeh (vinegar, for wisdom that comes with age), and sumac (for the sunrise of a new day).

With the 1979 Revolution, Iranian postage also transformed. The Shah’s portrait was removed and extant images of the old regime were overprinted with “Enqelaab-e Islami” (Islamic Revolution) or scratched out by hand. The most obvious symbols associated with the Pahlavi monarchy would disappear forever from Iranian stamps–the lion, sun, royal crown–while ancient objects that the Pahlavis appropriated to represent the monarchy would scarcely be seen again–the Cyrus Cylinder, the ruins of Persepolis.

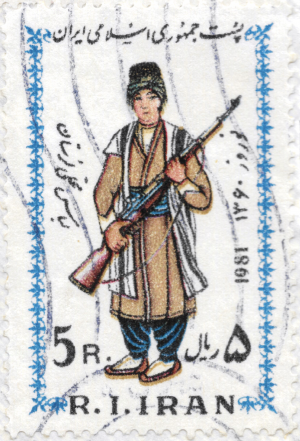

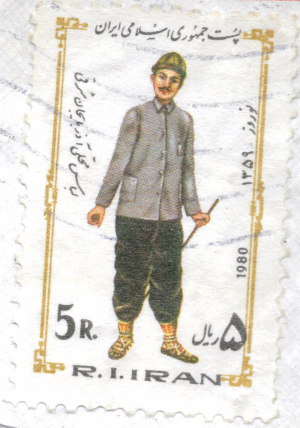

Nowruz stamps bear a more subtle marker of this shift: the changing calendar year. The last stamps issued by the Pahlavi government in 1978 featured the Shahanshahi year, 2538–visible on the stamp below with an illustration of a girl in Mazanderani clothing. The Shahanshahi calendar was carefully devised in the mid-1970s to link Cyrus the Great’s reign in 559 BC to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s ascension, which fell in the year 2500 in the new system. Iranians had previously used the Solar Hijri calendar, a solar calendar that dated its first year as the Hijrah, when the Prophet Mohammad left Mecca for Medina in 622 CE, which is also the first year of the Islamic calendar.

The imposition of the Shahanshahi calendar meant that the date changed from 1354 to 2534 overnight. The new calendar, however, was short-lived. The first Nowruz stamp after the Shah fled featured the restored Solar Hijri year, a pink rose, and the label “Bahar-e Azadi” (Spring of Freedom).

Despite these differences, the two governments employed the same visual elements to depict Nowruz–flora, fauna, and the clothing of Iran’s diverse ethnic groups. The stylistic continuity in Iran’s Nowruz stamps make them a marked exception to the wider aesthetic transformation that accompanied the change of guard.

The tools and styles of Iranian artists have driven the evolution of postal designs. A testament to the changing face of Nowruz, the Iranian National Stamp Council announces an open call for designs each year, usually during the month of Bahman, with a theme decided in advance. Themes have included food and health, birds of spring, and Nowruz around the world. This year, the committee asked for artists to submit designs interweaving the haft seen spread with the iftar table to commemorate the simultaneous celebration of Nowruz and the holy month of Ramadan.

Taken from my family’s collection, the stamps shown here were collected by my father and uncle who bought new issues from stamp dealers every new year during their childhoods. My grandmother then added more throughout the 1980s when her sons were outside Iran. While not necessarily valuable to collectors, my grandmother saw their cultural and historical value, saving them as mementos of the tumultuous times she lived through. As I recently began adding to the collection, it struck me that what began as a children’s hobby has become an archive that connects three generations of my family.

The examples presented here are just a sample of historical Nowruz stamps from across the region with representations of the spring festival from Soviet Azerbaijan and Tajikistan, pre and post-revolutionary Iran, and Iraq. These stamps show the interconnection of the Persianate world as well as its immense diversity with communities celebrating spring in multiple languages, with different traditions and wearing a variety of local clothing styles.