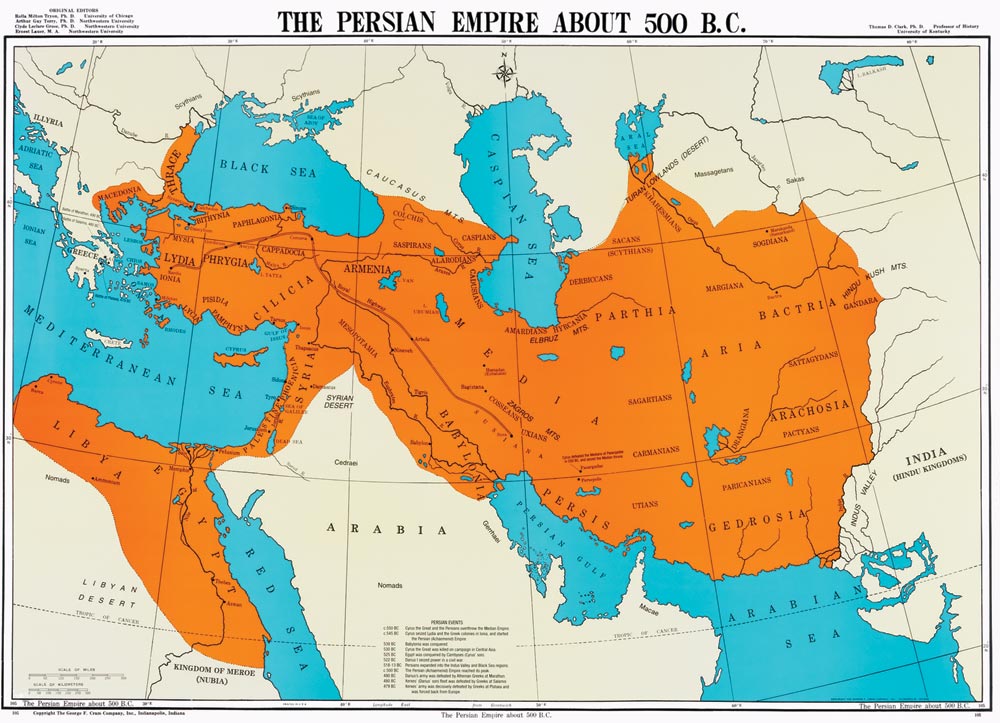

Recently, the Cyrus Cylinder, an imperial decree that dates from the sixth century B.C., left its home in the British Museum to be displayed on a museum tour across the United States until the end of the year. Its trip across the pond has been the focus of a plethora of news articles and press releases praising the ancient edict as the embodiment of “true” Persian culture and reminding the Iranian diaspora that this object purportedly bears witness to a democratic and tolerant past.

The excitement surrounding the Cyrus Cylinder is part of a broader phenomenon of rejoicing in a pre-Islamic past while simultaneously ignoring how its history has been systematically reinterpreted to fit contemporary political goals. This version of history is an ideological narrative that obscures nuance while inflating the relevance of an ancient history in the modern era. The legacy of the representation and misrepresentation of the Cyrus Cylinder is as old as the artifact itself. These interpretations are deeply intertwined with twentieth century Iranian history and the Pahlavi regime.

Since its rediscovery in 1879, the Cyrus Cylinder has been the focus of study for many generations of scholars, each hoping to elucidate the sociopolitical environment of Cyrus’ rule. The object, however, has been imbued with various and changing meanings informed by political and social circumstances not necessarily extrapolated from its contents since its rediscovery. The social biography of the Cyrus Cylinder is a compelling one, for its purpose has historically changed to match the needs of leaders in each time period, beginning with the era of Cyrus the Great until today.

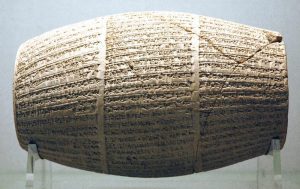

After the Persian imperial conquest of Babylon, the Cyrus Cylinder was written by the government in the voice of Cyrus II of the Achaemenids that addressed the people of Babylon in their language, Akkadian. It assured them that the Babylonian gods, especially Marduk, held Cyrus in good favor and allowed him to conquer Babylon swiftly, and that he would increase offerings of ducks and geese to the Babylonian gods to stay on their good side. It also claimed Cyrus made the sanctuaries of the gods permanent, and “gathered together all of their people and returned them to their settlements.”

According to Josef Wiesohofer, a leading scholar on Ancient Persia, the text of the Cyrus Cylinder can be divided into six distinct sections. It begins with a condemnation of Nabonidus, the previous Babylonian king, asserts Cyrus’ lineage, and then details Cyrus’ arrival in Babylon. It continues to outline prayers and sacrifices to Marduk, reaffirm that people are living in peace, and highlight Cyrus’ plans for erecting buildings.

Far from being progressive or unique, Cyrus allowed for the sacrifices and rebuilt areas to placate newly conquered peoples more swiftly. His edict used traditional Babylonian political processes and mimicked Nabonidus’ Cylinder in multiple ways, suggesting that Cyrus was imitating a commonly acknowledged political formula of his era. Both cylinders described the rulers as “king of kings, king of the four corners,” indicating a continuity in acceptable ruling titles in the region. Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, the role of religion is central to both cylinders. Much of both edicts are dedicated to describing the lengths at which the rulers, Nabonidus and Cyrus, took to restore temples and glorify the Babylonian gods.

Although Cyrus is believed to have been Zoroastrian, his cylinder makes no mention of the Zoroastrian deity Ahura Mazda, and only focuses on Marduk and other lesser Babylonian gods. The repetition of Marduk throughout the edict’s text was by no means random or a mistake; Cyrus chose Marduk to win the favor of the Babylonian people. The previous king of Babylon, Nabonidus, had privileged the moon-god Sin above all other gods, including Marduk, the primary god of the Babylonians. Cyrus had been mindful of the Babylonians’ discontent with Nabonidus and wanted to preempt any calls against his conquest by quelling their religious concerns.

Had Cyrus attempted to restructure social institutions in every conquered region, he would have failed in spreading his imperial sword as far as he did.

The Achaemenid dynasty followed Cyrus’ protocol and continued to use religion as a political tool to spread the Persian Empire as far as possible. For example, Cambyses II, the son of Cyrus II, worshipped Egyptian gods after his conquest of Egypt. It was not until Darius I that the Achaemenids definitively promoted themselves as Zoroastrians. By creating a divine connection between himself and Ahura Mazda, Darius I succeeded in consolidating political power in an otherwise tumultuous period. It is evident, then, that both Cyrus and Darius used religion as a means to further their own political careers and empires.

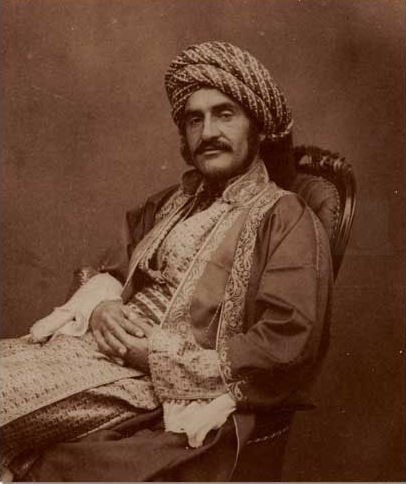

Fast forward more than two thousand years to the nineteenth century. Until 1879, the Cyrus Cylinder remained buried where it had originally been offered to the Babylonian gods. The Cyrus Cylinder was excavated in 1879 in Babylon, present-day Iraq, by the Assyrian-British archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam. European historians linked the cylinder to the Book of Ezra and the freeing of Jews from Babylon, believing the Cyrus Cylinder as evidence for the biblical story.

It was not for another century, however, that the Cyrus Cylinder would draw the attention of the Iranian public. Iran’s last shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, worked extensively to bring the Cyrus Cylinder to the fore of public attention to create an image that appealed to his people, as well as others worldwide. The popular understanding and glorification of the Cyrus Cylinder, commonly referred to now as a symbol of religious freedom, is rooted directly in modern Iranian politics of the twentieth century.

Mohammad Reza Shah took the Cyrus Cylinder and liberally interpreted the sacrifices as a promise of religious freedom. Drawing upon Cyrus’ Biblical legacy, Mohammad Reza Shah presented the Cyrus Cylinder as a defender of all religions, removing it of its specific imperial context and creating a symbol of religious freedom where there was none. He then declared the Cyrus Cylinder as the “First Declaration of Human Rights” in 1968, hoping to bring positive attention to Iran’s history to deflect the international community’s increasing criticism of his authoritarian rule. A few years later, Mohammad Reza Shah organized the incredibly ostentatious anniversary celebration of 2,500 year monarchical rule in Iran. In the same year, to further commemorate Cyrus II’s rule, the Shah gifted a replica of the clay artifact to the United Nations in 1971.

During his rule, the Shah was accused of widespread human rights violations for torturing and executing political opponents to his regime. So brutal was his reign that Amnesty International eventually identified Iran as the world’s top human rights offenders in 1976. In particular, the infamous cruelty of Iran’s secret police SAVAK had tarnished Mohammad Reza Shah’s progressive image. In order to draw attention away from these egregious abuses, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi launched a campaign to connect his rule with that of Cyrus the Great. Ironically, the idea that the Cyrus Cylinder was the first human rights document emerged from the lips of a dictator. His campaign to recreate Iran’s public image was often linked to a racialist agenda of Persian supremacy at the expense of a more cohesive national identity.

Despite the Shah’s attempts to make his autocratic rule more popular amongst Iranians, his extravagant spending on the 2,500 year anniversary celebration of monarchical rule backfired and provoked even more discontent amongst people. Mohammad Reza Shah is responsible, however, for inventing a new life for the Cyrus Cylinder—one which has been used by Persian nationalists of all stripes to reclaim the ancient empire.

Pahlavi’s attempt to restore dignity to his throne has spawned a tradition of romanticizing ancient Persia in order to deflect attention from contemporary struggles. Since the 1970s, many Iranians have been guilty of exaggerating the contents of the Cyrus Cylinder, claiming that Cyrus freed all slaves, allowed himself to be democratically elected by Babylonians, and promised freedom of religion. These claims, among others, are either entirely fabricated or dramatic deviations from the text. In fact, Babylonia was expected to send a tribute of 500 slave boys to the Achaemenid king every year. And yet, these are the most commonly cited “values” of the Cyrus Cylinder. Scholars, including Josef Wiesehöfer, C.B.F. Walker, and Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones have done scholarly research on the Cylinder and the social milieu discounting these claims. These exaggerations helped legitimize Pahlavi’s regime by reinventing the past to distract from the present.

Thanks to Mohammad Reza Shah’s campaign, some contemporary Iranians refer to the Cyrus Cylinder as if it were the answer to current problems faced in Iran and in the diaspora. The Cylinder has become a source of pride for many, but unfortunately this esteem recycles a dictatorship’s fantastic projections onto an artifact of empire, repeating the process of inventing a noble back story instead of addressing the misuse of history for contemporary political projects.

The Cyrus Cylinder continues to be re-appropriated in a similar fashion by government elites today, denoting continuity in two governments’ approaches towards Iranian antiquity. During the Cyrus Cylinder tour to Iran in 2010, the Cyrus Cylinder was unveiled underneath the Iranian flag, and a Cyrus impersonator was honored by Ahmadinejad with the gifting of a chaffiyeh, worn by soldiers in the Iran-Iraq war and identified with the Basiji paramilitary today. The combination of current national symbols of the flag and chaffiyeh with Cyrus the Great and his cylinder indicates a desire to create a holistic national identity, drawing upon both an ancient imperial legacy and a modern culture imbued with Islam.

Ahmadinejad’s welcome, which tied the present day to the past, resembles Pahlavi’s recreation of the symbol in the 1960s and 70s, as both tried to link their own rule and modernity to that of Cyrus II. His attempt to co-opt the secular nationalist symbol and subsume it under a religious nationalist identity, however, backfired in many ways. His actions estranged other factions in the government, revealing the controversial nature of the Cyrus Cylinder in the eyes of some government officials today and leaving his reverence of the artifact to be ridiculed.

This year, the Cyrus Cylinder is on loan from the British Museum, touring the US from March 9th through December 2nd, making stops in D.C., New York, Houston, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Disturbingly, the Cyrus Cylinder has been welcomed to the US by the same American congressmen who have pushed for devastating economic sanctions in Iran (see here and here). By touting the Cyrus Cylinder as the foundation for future human rights charters, some have seen the celebration of the historical artifact as a way to counter the current media blitz on Iran’s nuclear program. Historians and archaeologists of Iran, however, recognize these claims as the projection and downright insertion of modern values into an ancient text.

The meanings of objects change based upon the perspectives of the reader. A 2,500-year-old object should be analyzed in its own context, not through twentieth century universalist legal definitions. By accepting the lofty claims made about the Cyrus Cylinder, we are not only promoting false deviations from the text, but we are privileging an imperialist narrative that deserves scrutiny. Through demystification and demythification of these objects, one can better analyze the development of nationalist symbols in the modern period and their ability to obscure realities of the present and the past.

26 comments

thank you for this article. I have waited for an article that could have highlighted these points for some time now (maybe i wasnt looking hard enough). Well done and more ppl should read this. Keep up the good work. p.s. a chronological summary at end would have been helpful, usually difficult to follow timelines so expansive :))

It never even occurred to me to actually read what the cylinder said. All of us just assumed it said what we thought it said, as if we just projected our own ideologies onto it.

Whatever the cylinder say or don’t, two points are certain:

A) The contents of the cylinder have little bearing over how we should perceive modern Iranians (and by that I mean citizens of the state of Iran).

B) Historical revisionism is nothing new. Read the local history book from any country and it’s filled with local heroes and their humane deeds. In Mongolia, I’m pretty sure Genghiz Khan is revered as the holiest of men.

Using the Cyrus cylinder to glorify Iran’s past neither feeds the starving nor provides medecine for the sick. It doesn’t even make sure that their human rights are respected – the very ones the cylinder purportedly enshrines in it. And that’s quite obvious in the many ways that it has been used by tyrants.

The concept of modern human rights is a collective human achievement. Its greatest champions have been diverse people from all continents. If we love human rights, then we’ll work towards implementing them.

If you love Cyrus… or wanna blow the Persian horn, go ahead, but that will only boost egos.

I think the article makes all those points and more quite nicely and articulately I must add.

If the name of the article was unknown I would have sworn it was written by a Eurocentric! Having said that when the writer mentions Josef Wiesohofer and declares him as the leading scholar on Ancient Persia, it becomes apparent that Ms Beeta has no clue abut the topic! Josef Wiesohofer along with Amelie Kuhrt, Pierre Briant and Wouter Henkelman are leading Eurocentrics who absolutely despise the pre-Islamic Iranian civilisation.

Ma advice to Ms Beeta: Stick to the Qajar era and leave the Pre-Islamic Iranian history to the experts of the field!

Sorry, I meant: If the name of the writer of the article was unknown . . . .

Hello, to quell your concerns about my training, I wanted to let you know that I focused on ancient Iranian history prior to switching to the Qajars. You are absolutely right about the field being dominated by Europeans, Germans especially, and for that reason scholarship on ancient Iran usually has an Orientalist slant. I would differ with you on your point about “despising the pre-Islamic Iranian civilization.” Quite the contrary, I believe most European scholars of the tradition are very much enamored with Ancient Iran. It was a fascinating era.

Line 26- “I soothed their weariness; I freed them from their bonds(?). Marduk, the great lord, rejoiced at [my good] deeds”.

Who is Cyrus referring to and did he actually do anything?

Hi Samira, this is a great question. As you noticed, there’s a question mark after “bonds,” so even the top translators of Akkadian are not sure if that’s the correct word. Regardless, the “them” could have referenced the general Babylonian population, since the rule of Nabonidus was presented as incredibly oppressive by the Cyrus Cylinder. Beyond that, though, the knowledge we have about slavery during the Achaemenid Empire undermines any possibility that Cyrus “freed all slaves.”

If Cyrus’ cylinder has been around for at least 2,000 years, and many contemporary scholars have studied its origins, why haven’t they drawn similar conclusions?

If they have, then why are your references mainly wikipedia and other unverifiable websites?

I can certainly appreciate a new take on the matter, just wished that there was more substance to back things up.

I think all should read this with a grain of salt.

Hello! I appreciate your skepticism–most people are too quick to believe what they read on the internet. The thing is, contemporary scholars have drawn similar conclusions to those that I have expressed in the article. Unfortunately, these conclusions haven’t gone viral on the internet, whereas false translations have–a doubly disappointing situation for those of us in academia. The links in the article were mainly wikipedia links because that is all that is available on the internet to a non-paying audience. I didn’t think it would be fair to link to scholarly articles in JSTOR, usually only available to those affiliated with universities.

If you would like scholarly references, I suggest Josef Wiesohofer’s “Ancient Persia” (which I can vouch for personally, is taught at universities, and is cited in the article). For references on modern Iran, read anyone from Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet, Kamran Aghaie, Houchang Chehabi, Cyrus Schayegh, and Mohamad Tavakolli-Targhi who have all dealt with the issue of nationalism and it’s restructuring of our history. Unfortunately, their works are not readily available on the internet for us to use, although I did cite Aghaie’s book in the article, which is partially available through Google Books.

The text of the Cylinder is very specific, listing places in Mesopotamia and the neighboring regions. It does not describe any general release or return of exiled communities but focuses on the return of Babylonian deities to their own home cities. It emphasises the re-establishment of local religious norms, reversing the alleged neglect of Nabonidus – a theme that Amélie Kuhrt describes as “a literary device used to underline the piety of Cyrus as opposed to the blasphemy of Nabonidus.” She suggests that Cyrus had simply adopted a policy used by earlier Assyrian rulers of giving privileges to cities in key strategic or politically sensitive regions and that there was no general policy as such.

” It does not describe any general release or return of exiled communities but focuses on the return of Babylonian deities to their own home cities”

Except that it does:

https://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/articles/c/cyrus_cylinder_-_translation.aspx

30.brought their weighty tribute into Shuanna, and kissed my feet. From [Shuanna] I sent back to their places to the city of Ashur and Susa,

Akkad, the land of Eshnunna, the city of Zamban, the city of Meturnu, Der, as far as the border of the land of Guti – the sanctuaries across the river Tigris – whose shrines had earlier become dilapidated,

the gods who lived therein, and made permanent sanctuaries for them. I collected together all of their people and returned them to their settlements,

and the gods of the land of Sumer and Akkad which Nabonidus – to the fury of the lord of the gods – had brought into Shuanna, at the command of Marduk, the great lord,

I returned them unharmed to their cells, in the sanctuaries that make them happy. May all the gods that I returned to their sanctuaries,

every day before Bel and Nabu, ask for a long life for me, and mention my good deeds, and say to Marduk, my lord, this: “Cyrus, the king who fears you, and Cambyses his son,

may they be the provisioners of our shrines until distant (?) days, and the population of Babylon call blessings on my kingship. I have enabled all the lands to live in peace.”

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/cyrus-iv

“Cyrus continues in the first person, giving his titles and genealogy (lines 20-22) and declaring that he has guaranteed the peace of the country (lines 22-26), for which he and his son Cambyses have received the blessing of Marduk (lines 26-30). He describes his restoration of the cult, which had been neglected during the reign of Nabonidus, and his permission to the exiled peoples to return to their homeland (lines 30-36). ”

Beeta conveniently neglected that part whilst making hay out of “increasing offerings of ducks and geese to stay on their good side”

Here, the cylinder is saying that Cyrus restored sanctuaries of the gods of exiled peoples held by the Chaldeans in Babylon (Elamites, Assyrians and others) and that he “returned them to their settlements”) The relocation of conquered peoples and religious or other relics was a common practice in ancient Mesopotamia, but never had anyone allowed these peoples to return and returned and actively patronized the re-establishment of their religious shrines upon their permitted return. (The stele of Hammurabi, for instance was found in southern Iran, where it had been for nearly 3,000 years. Why? An Elamite sacking of Babylon brought the famous Mesopotamian law code to Iran as plunder)

This is corroborated by the Old Testament accounts of the Jews celebrating Cyrus’ decree that the Jews be returned to Israel and the temple be rebuilt.

Beeta is absolutely right. The more salient point I agree with is the mistranslation and misappropriation of an ancient inscription to create an ideological distinction between the “glory of ancient Persia” and Islamic history. Unfortunately many Iranians have been sold on this idea that everything Islamic is bad and therefore the pre-Islamic period is some kind of golden age for “Aryans.” While scholars and intellectuals have long dispelled notions of race and collective identity, the Iranian nationalist narrative is still alive and well. None of the criticisms posted above can dispute that the cylinder, and history itself, is an object that can be distorted for the purposes of either propping up the Shah’s legitimacy, denouncing the IRI, or both.

To “a bit wary”: There are many scholars of ancient Iran who know this, the problem is that misinformation has been spread among the Iranian community for reasons Beeta outlined above. Most Iranians don’t know about this research because the false translation is ubiquitous. To get the accurate perspective, check out Touraj Daryaee’s work.

Beeta, in a future article you should post the distorted translation alongside the British Museum’s translation so people can compare for themselves. I applaud your courage and look forward to reading your future book.

More or less spot on! A thousand more of these articles and the nationalists might just start paying attention. Just a minor quibble, though: Darius did not promote ‘Zoroastrianism’, which term doesn’t come into being for centuries later. Rather he promoted the idea that he and his dynasty were authorised by Ahura-Mazda. Zoroastrianism in the form we know it didn’t exist then – indeed, while its elements, including the Avesta and Zoroaster himself are extremely old, as a ‘religion’ it has been shaped in response to the rise of first Christianity and then Islam. For centuries in the Iranian world Ahura Mazda was worshipped alongside (although often superior to) other gods (Anahita, Mithra etc.). If we need a label at all (and remember that ‘religion’ the way we use it is a modern Western idea – see Talal Asad’s ‘Genealogies of Religion’), then ‘Mazdean’ is probably more appropriate.

I am surprised that you have suggested that there was slavery in ancient Persia!! Where as there are thousands of tablets ‘Payment recite etc…’ left from the time that they were building the Persepolis!!?? The only ancient massive construction which wasn’t built by salves as it was a norm in all the ancient empires at the time or even recent ones!

Also, if even Cyrus the Great use the religion tolerance as a tools to expand his empire, why we can not find any other example (e.g. Greek of Roman) of such a treatment in ancient history!!

In the Persepolis ruin you can see peace harmony and happiness between all races, where as in Greece and Rome seen of swagging, slathering and of course sex and homosexuality!!

Not always you get famous by swimming against the current and being controversial, sometime it’ll backfire!

The fact that Persepolis was constructed by paid workers does not mean that slavery did not exist in the Persian Empire. In fact, it is pretty clear that slavery did exist, under Cyrus and his successors. The sources I can find do indicate that slavery was less widely practiced in Persia than in many ancient societies, but it did exist, along with other, more voluntary forms of servitude in return for food.

Paid laborers built many structures in the USA before the Civil War, but slavery was still a widespread and brutal practice in the country during that time. Persepolis is remarkable for having been built by free labor, but it does not indicate that slavery was nonexistent under Cyrus.

Beeta joon – You’re out bicycling in territories you obviously know nothing about – and while doing so – you’re reunning the errands people who for some unknown reason despise Iran and everything about it. Just the fact that you take yourself the liberty to express the intentions of Cyrus the Great, without even having known the man – who btw lived 2500+ years ago, tells me that you have an immature perception of the whole subject… Stick to things you know…

This is a very unsophisticated article of low quality! While Persian nationalists – like nationalists anywhere – have a tendency to resort to fabrication serving to aggrandize their past and their present – this attack against a truly great King and leader is based on nothing more than presumptions and false premises… serving who one might ask…

Beeta joon – Did the Saudis deposit your money directly into your account, or did they send you a check?

I am thankful for you to draw the readers attention to the construction of myths around the Cyrus cylinder. For those who read German, there is an article on the same subject on Alischirasi’s weblog, with some updates on how Cyrus himself is becoming the object of veneration in present day Iran.

with best wishes

Georg Warning

http://alischirasi.blogsport.de/2015/01/02/ein-gespenst-geht-um-im-iran-die-menschenrechtserklaerung/

http://alischirasi.blogsport.de/2017/10/30/iran-ruhe-in-frieden-kyros/

http://alischirasi.blogsport.de/2016/10/31/iran-massenkundgebung-fuer-kyros-ii/