Emerging Scholarship is a series showcasing the research and interests of new voices emerging from academia that focus on the social worlds, histories, and traveling cultures of Central and West Asia.

Our first podcast is with Dr. Neda Maghbouleh, where we talked to her about her upcoming book, The Limits of Whiteness: Iranian-Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race, under contract with Stanford University Press. Neda Maghbouleh is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Toronto Scarborough. Her research examines the production of racial categories and identities through macro-level policy and micro-level interaction, with a special emphasis on Iranians and other “liminal whites” in North America. Dr. Maghbouleh’s work has been funded by the National Science Foundation, UC Center for New Racial Studies, American Sociological Association, and National Women’s Studies Association. She has a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of California, Santa Barbara and lives in Toronto, Canada with her husband, Clayton, and their infant daughter, Neelu.

We spoke with Dr. Maghbouleh at the International Society of Iranian Studies biennial conference in Montreal, Canada, in August of 2014. Our interview with Dr. Maghbouleh focuses on race and racialization in the Iranian-American context, particularly amongst second-generation Iranian-Americans and their families.

1) AjamMC: Neda, it’s so great to see you and talk to you about your book. Could you give us a brief intro to your work for those unfamiliar?

NM: Hi Beeta, it is so awesome to be part of the Ajam-ily (laughs) today. I’m a big groupie of the site, so it means a lot to me that you would invite me to contribute, thank you.

My work really takes up the idea that Iranian-Americans live a racial paradox. In terms of the state, the state clearly understands and treats them supposedly as the “whites” that they’re categorized as, yet in their everyday travels through the world, Iranian-Americans are not treated as the whites that they are legally. I’m interested in that paradox and where it becomes relevant, so I try to focus on those sorts of things, in particular with the second generation, young Iranian-Americans born here in the US … but we’re in Montreal right now (laughs), so “here” is not quite what I meant.

For example, I’m a sociologist. We have this long tradition in sociology of studying when “brown” groups or groups that have been racialized become white. It’s usually a story of impugning other minorities, ascending through social class, becoming rich enough to become white, and my case is really interested in the opposite. What happens when a group that has historically been categorized as white has enough racializing experiences such that it’s not when brown becomes white, but when white becomes brown.

2) AjamMC: So interesting. One of the strengths of your book is the focus on the everyday struggles with race. I was wondering if you could elaborate on some the coping strategies you found that Iranian-Americans use to deal with the everyday tensions and racialization that they face.

NM: When I talked to youth about the kinds of experiences they would have, let’s say in the classroom with teachers or with authority figures in the spaces they live — playgrounds, shopping malls — I notice that these youths are really pre-occupied and hurt by the disconnect they felt internally as someone with a unique past, a unique history that wasn’t being recognized by the broader state.

One strategy I found these youth use is to delve into their own history. Rather than the assimilation that a lot of sociologists would imagine would happen, you see a lot of these second generation youth going into the library on their own, googling self-directed “research” about their roots. And not just passively taking that stuff in, but being really critical about it too and trying to find a place for themselves in the “story of Iran.”

Also, a particularly American tweak on this is that a lot of these youth link up with other people from racialized communities. Finding common cause with Latino classmates, black roommates, Asian-Americans, in particular Arab-Americans and other racialized groups from Southwest Asia and North Africa. These are people that traditionalists might say would be strange bedfellows to Iranians, but in fact, in the second generation, you see these youth coming together. This is a complementary strategy to know one’s own history, but then also to seek out those common ground connections with others.

3) AjamMC: I noticed in your book you’ve referenced the history of racialization that happens with Arabs and Armenians in the 20th century during their campaigns to be identified as white by the U.S. government. You mentioned that they used Iranians as a foil for their identity, that Iranians were brown when they were white. It wasn’t until the mass emigres of 1979 that Iranians were labeled with this same whiteness. Could you speak to them being strange bedfellows, and also whether or not there’s an argument for a greater Middle Eastern identity that’s being fostered today, especially after 9/11?

NM: I’m glad you asked about this, because that is something that emerged out of my research that I hadn’t even necessarily expected, but it became a really big thread that linked a lot of youths’ stories. In particular, I noticed a generational divide that they would describe. They had first-generation parents who would sometimes imbue the family with this sense of Iranian exceptionalism. For example, they would say “our history is something unique, something special, the Persian language had the ability to live on” and that’s supposed to be exceptional about our “people,” and as a result, you have a generational divide that our youth are always talking about. From their parents, they get a message that Iran is quite exceptional and we are quite exceptional, but then they grow up in the US, where politics is completely infused by pan-ethnic movements, that the way that groups are able to seek redress is through banding together with other groups, and very often this is a pan-ethnic coalition. For example, “Asian-American” didn’t exist before the 1960s, but it was the Vietnamese coming together with Filipinos and the Koreans and the Japanese across their differences. I think that young people grow up both intuiting that, but also learning history in the classroom.

For these young people, after something like 9/11 when clearly Iranians were being lumped together with these different groups, what these parents were telling them about Iranian exceptionalism begins to fall flat. Of course, they’re going to make connections, not just to Arabs and Turks, but also South Asians: Indians, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis. I think that we can start to talk about a Middle Eastern identity that’s different than the one we see at a conference like MESA [**Middle Eastern Studies Association, a major academic organization for those interested in the study of Southwest Asia and North Africa] or we read about in a textbook. There is a ground-up Middle Eastern consciousness and group identity that’s forming with kids in this generation, coming of age.

4) AjamMC: So going off that, what role does religion and secularization play in this? It seems like a large part of the Iranian identity is concerned with disregarding religion, but could one also see how religion becomes a bigger part of fostering bridges across Middle Eastern Muslim-Americans?

NM: Oh, very much so. Not only does Islam operate differently for this generation of Iranian youth, that even if they grew up in a secular household, they don’t necessarily have a knee-jerk reaction one way or another to Islam. Though they may be secular themselves, they don’t shy away from learning more about the impact of the religion, both in a social justice framework, and also in an Iranian historical framework, and by making crucial links to Muslim communities or other Muslim American communities.

5) AjamMC: And that differs from their parents?

NM: I would say so (laughs). Of course, I’m essentializing to some extent, and I have exceptional cases throughout my research, like the first generation parents who were kind of radical, or the ones who came to a sense of racial consciousness much later. And I love those stories, and I think those stories are important, but they are also the telling cases because they come up so rarely, that they also speak to the silences, too.

6) AjamMC: Right and I don’t mean to essentialize your research by any means. Talking more about the exceptions, did you come across Iranian-Americans who did actively identify as white, critically or uncritically? How did they come to this conclusion? How did they justify it? Or if not, was it just an identity that they expressed?

NM: Well, as a sociologist, working in a tradition that is ethnographic and qualitative, you always have to be wary about your research population, the participants. Are certain people attracted to your project, wanting to contribute because they share a sort of like-minded politics? Or approach?

For the most part, the youth I spoke with did not identify as white. They were either quite resistant to it, or expressed something like “I try not to think about it because it vexes me, and I can’t make heads or tails of it, so I’ve decided not to think about it.” There is either youth really engaged with it and push back against it, or the ones who say it gives me a headache, because I don’t know where I stand…

I would say I did come across a few cases where people felt it was begrudging acceptance. That’s what I would call it. They begrudgingly accepted it and would say “this is the label that the government or the state has given to our community, and I get it, because Iranian-Americans have a particular median income [corrected from earlier transcription], or they tend to have particular professional occupations, so I’m not going to push too hard on this whole white thing, because it some ways we kind of are–elbow elbow nudge nudge.” (laughs). There was a begrudging acceptance. But again, I don’t know if that’s because I wasn’t able to seek out people who either critically or uncritically identified as white, or if that was just the limitation of the kind of research I was doing.

7) AjamMC: That’s really interesting, because that becomes its own sort of coping mechanism — not dealing with it — that group that said it ignores this whole thing. As you know, my own research focuses on race and slavery in the Iranian context, so I’m not a diaspora scholar of Iranians, but I am of slaves and their descendants. And I’ve noticed in my own experiences that different generations of Iranian-Americans or Iranian immigrants respond differently to my work.

The older generation of Iranians who grew up in Iran, generally, are much more resistant to my research. Iranian Americans, on the other hand, express more interest in it. They think it’s kind of cool; they don’t necessarily tell me that my research is wrong, which I hear a lot from older Iranians. Have you noticed a similar trend or divide in the reactions from the Iranian community, since you also work on race and your topic could potentially be marked as taboo? What do you think?

NM: This is a general area that I’ve been academically obsessed with for a large part of my life. It was the subject of my undergrad thesis, and I did a version of it for my Master’s, and I went back to it for my Ph.D… so it’s been an obsession for going on over 12 years! But what’s interesting is that through the life course of these projects, I’ve even seen a change, in particular with the first generation, folks as parents, who were the original immigrants to the US. Even from my undergrad thesis to my Ph.D., I have sensed that there has been a shift in the kind of average response that I get, whether that’s from talking to youth’s parents, people who are under 18 and I need to talk to their parents to get permission for them to be in my project, or whether I run into people at the supermarket and we start just to talking.

I did get quite a vociferous reaction at first, let’s say ten years ago, when I was looking at doing a project like this. It was a knee-jerk reaction: “we’re white and that’s all there is to it! Leave well enough alone.” And I think it was a feeling of, “look at what we did for you, we came here, you all grew up in great neighborhoods! And you benefited from these sorts of sacrifices that we made, and so why are you trying to rock the boat??”

That was definitely the normative response that I would get at first. But a lot has changed, in particular, I think that in this same way that the second-generation youth in my research have come of age, I think their parents also have too. And that’s been one of the coolest things to see–tracking the first generation and the ways in which very strongly-held opinions can change whether it’s about things like race, or issues around sexual orientation.

There’s been such a growth and a trajectory that I wouldn’t have ever expected from folks as parents and grandparents. One of the most rewarding parts of my research has been checking back in with young people who might have described some sort of conflict that they had in their families. When I follow up with them 1 year, 2 or 3 years later, they say, “my parents have come around.” Sometimes it’s because they watch the Ellen DeGeneres Show, or they heard a really funny black comic on Key and Peele. This is a true story– they say “my parents saw an episode of Key and Peele and it made them think” or whatever. But, somehow, someway, everyone’s views are starting to evolve, and I think that’s really cool.

8) AjamMC: That is really cool. Going further with this idea of the parent-child divide, you draw upon the idea of having multiple races within one family. You even suggest that the divide between the parent and child experience could qualify as a different racial expression and classify it as an interracial family experience.

Could you talk about the role accents play in your research? Broadly, generalizing, of course this isn’t true for everyone, but parents who were immigrants probably have more of an accent than their children who were born and raised in the US. It seems counterintuitive that these parents may feel racially more comfortable and more accepted within society, whereas their Iranian-American children without accents felt more marginalized?

NM: Well, most of these families that are part of my study, the children are born of the 2 parents, they’re the “same blood.” How could they be different races if they all come from the same lineage? My inspiration for that is that the most classic case to study race in sociology is the country of Brazil. This idea that a country could have 200 different racial designations, it could be this place where people could be categorized along so many different axes. Truly, in Brazil, if a census workers goes to a house, they could assign family members who are all biologically-related a different racial category, because the way that they ascribe race has to do with [things like] the texture of your hair, and, of course, skin tone. These are the features, such that people who are legitimately related in those families can be different races.

I was thinking through that and it helps me explain some of the dynamics I see in the Iranian home, where parents may cling really closely to a kind of white identity that they were inculcated with in Iran that they brought over with themselves, for better or for worse, in the US. But there are these youth who have very racializing experiences–to the point where they say I don’t identity as white and say, “it doesn’t make sense for me.” So you have these people who are biologically related, but insist on these different self categories. That’s where having multiple races in the Iranian-American family becomes alive in the research.

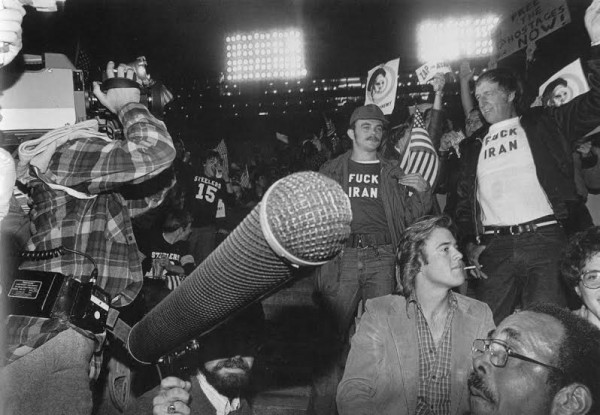

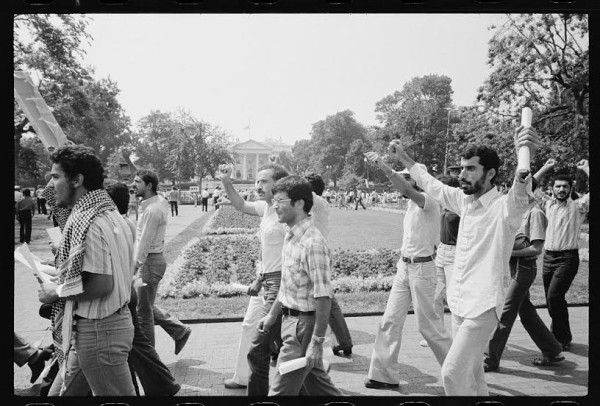

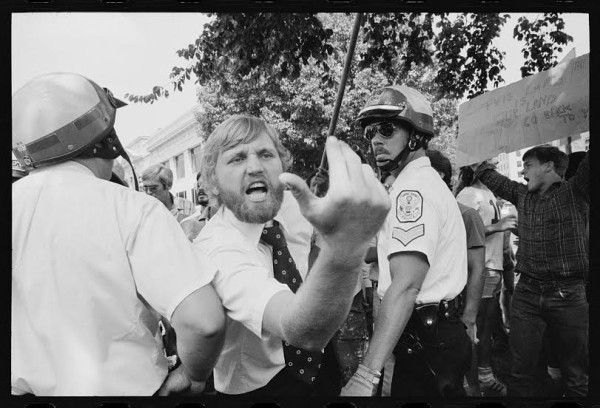

The issue of accents that you raised is so important, because though I’ve talked about racializing experiences that second generation kids have at school or at the mall, something like that, in fact, once you start to dig around the family, and you start to hear the stories that people don’t necessarily want to share right away. But then they do tell you about them, and it’s often times the parents bearing the brunt of a lot of hostility and discrimination, simply because they are actually outside the house quite a lot…managing the bills, going to the bank, going to the grocery store. So when these kids are growing up sometimes they are with them on these errands, but in fact it’s their parents who are navigating this world, and if we think about the world that many of these parents were in, shaped by the Iran-Contra Scandal, the Hostage Crisis, once you start to actually dig around, issues like accents structure the kind of discrimination and the outsized way in which the parents did bear that weight.

Now, the extent to which parents do share those experiences with their children, and are honest about what has happened, that’s been interesting and variable across families. Some families don’t want to talk about it, because you’re trying to be strong for your kids. You don’t want to necessarily tell them about how someone was really rude to you on the phone, a customer service representative, and they said, “can you give me someone who speaks English?? I can’t understand your accent,” which is a really common story that I hear from the first generation.

I’ve noticed that as these second generation kids get older, parents are more forthcoming about these troubling experiences they’ve had. But I understand too, from their perspective, you want to shore up a sense of pride for your kids and who they are, and you don’t necessarily want to tell them about those kinds of struggles.

9) AjamMC: That’s really revealing. I just wanted to touch on Twitter and Facebook as well, since you mention it in your book, and I was hoping you could elaborate on how social media has helped (or not) foster discussions on race and racialization.

NM: Although I never set out to talk about social media, and I’m not a scholar of social media, it is so deeply incorporated in the way people move through the world, the way they communicate with their friends, and how they express themselves. A lot of the way they narrate their own lives — it happens on Instagram through images, or it happens through a tweet that they shoot off after something messed up happens to them. And so, this stuff ends up becoming part of the data, because it’s just how people and the way life is now.

What’s really cool about how social media has helped Iranians have a place at the table, in terms of discussions of race and racialization, is that it connects back to what you asked about coping strategies…That in fact, Twitter, Facebook, those sorts of spaces allow Iranians to communicate with other communities of color in a timely way, such that when something messed up happens, whether it’s in the media or in politics, and people are looking for responses, I’ve noticed that Iranians are now called to the table. There’s a “people of color” or “women of color” politic of wanting to have these kinds of liminal voices, knowing that they’re there and seeking for them to be a part of the conversation.

I would say who tends to be sort of surprised about Iranians being involved in racial politics is white people. Who’s not surprised about Iranian-Americans being involved in racial politics? Other people of color, who have always been like “y’all aren’t white!! Please!” (laughs). That’s been my experience both academically and also socially with friends.

10) AjamMC: That’s so true. I’ve had the same sort of experiences as well. So lastly, going off what you just said, because to everyone else it’s obvious that we’re not white (laughs) I mean, maybe I’m biased, but there is this nationalist Aryan myth that tells us that Iranians are white or are the “true Aryans.” It’s been fairly persistent, even though Iranians come in a range of skin colors, a range of complexions and phenotypes…

How has this lasted for so long? Why haven’t more people been more critical of it and said, “You know, I’m actually pretty dark skinned, and I don’t know what white means anymore,” or “Does white mean Western European, and how do I link myself to them?” or as you know, the ever-famous quote, “You’re whiter than Europeans!” which so many of us have heard from our parents. How does this all tie in?

NM: Well, first of all, I think you’re dead on, that yes, this is still so common. We can have these academic conversations about “Come on, we’re not really white,” but at the end of the day, the Aryan myth still lives on. So why? I think, as a people, and I put “as a people” in quotes, but as a people, “we” are fond of myth, generally. [We enjoy] linking or unearthing this particular grand past and connecting ourselves with it, and the Aryan myth is similar to that. And so, “as a people,” it seems like something we do quite often.

More generally, and this is not specific to the Iranian case, but people are loath to give up power or privilege. We can have all of this data that suggests that Iranians do face a lot of discrimination in terms of employment, they do face discrimination in the classroom, or the housing market, and yet, of course, there’s going to be a tendency to not want to cede power. So, if we have something like the Aryan myth, why not marshall it? And I’m not a psychologist, so I can’t speak to the kind of psychic work that it does for people, but I can say sociologically, yeah ok, there are really discrete benefits to whiteness. But in terms of my work, I think we also gain a lot by giving it up, too.

8 comments

While I understand that the state, according to the census, seemingly categorizes Iranians (and people from North Africa and the Middle East in general) as “white”, I disagree that it treats us — even lighter-skinned Iranians — as white. (Dr. Maghbouleh, you do say “supposedly”, so maybe we’re in agreement.) I would also argue that our everyday experiences with racism (from non-state actors) are, in fact, heavily influenced and informed by the state’s policies and practices — from the local to the federal level, domestically and abroad — not only post-9/11, but also pre-9/11.

(Middle East of whom, by the way? And who’s included in the so-called Middle East? Flawed census designations shouldn’t tell us who we are. It’s especially ridiculous when we consider the sheer diversity — phenotypic and cultural — within the region as a whole as well as individual countries. And shouldn’t we parse the differences between nationality and race? I should also mention that I feel like 9/11 often serves a seductive and increasingly illusory purpose in our discourses regarding race, religion, and politics. It intensified everything that already existed — the heat was already on, and it brought things to a boil.)

Not being “treated as white” sounds a little weird, too, as if we should be invested in attaining that status and should be disappointed when we don’t — nah, not at all. I want all of us — and all people of color — to be treated as human. I don’t think we should be trying to gain access to whiteness, not only because such attempts are inherently predicated on white supremacist ideology, but also because I reject the notion that Iranians are “white” [1]. I can’t dictate how anyone identifies, but my assertion is more than just a statement of belief, especially when considering that our non-whiteness is a reality for so many. (Though sometimes useful, even using a term like “non-white” further centers whiteness.) All this being said, I realize that we’re fundamentally talking about definitions of whiteness, and I understand that others might disagree with me.

Brown-to-white and white-to-brown transformations were mentioned, but what about those of us who have always been brown? Before and after 9/11 — be it because of how we present, how we identify, or both. I worry that discussions on race often seem to operate with the assumption of a monolithic Iranian identity. I’m guilty of this, too — even in this comment. We all aren’t treated the same way. (Who are “we” anyway? When can first person plural pronouns be useful? When are they harmful? What other ways might there be to talk about who “we” are?)

And even when we do acknowledge our differences, I feel like oftentimes we still exclude black Iranians. I wonder how that connects with all of this as well, especially given the fact that many groups throughout American history have tried to assimilate (and succeeded in doing so) by contrasting themselves with black people. That’s another reason why I believe that those of us who are lighter-skinned shouldn’t attempt to gain access to whiteness — doing so ultimately serves the white supremacist project, further perpetuating anti-black racism [2] and colorism within our communities. Rejecting whiteness, however, does not absolve lighter-skinned Iranians from recognizing and interrogating their light-skinned privilege.

(I say all this with the understanding that these color-coded classifications — black, brown, white — don’t necessarily operate the same way outside the American context.)

In part 6, the transcription reads, “…median in color (i.e. tend to be relatively more light-skinned on average)”– according to whom? Compared to whom? On what scale? What does it mean to even consider an “average” Iranian skin color? Do we also imply an “average” Iranian experience? And in what ways can this contribute to the construction of a monolithic Iranian identity? When we talk about the limits of whiteness in this context, I feel like we’re only talking about a subset of the Iranian population — lighter-skinned Iranians in closer proximity to whiteness. For many of us, whiteness is not an option. (I should note that when I listened to the podcast, I heard Dr. Maghbouleh say “median income” as opposed to “median in color” — I’m addressing the transcription.)

Regarding religion, Ms. Baghoolizadeh states (in part 4), “It seems like a large part of the Iranian identity is concerned with disregarding religion…” — are you referring to Iranian identity in general or Iranian-American identity in particular? Specific communities within the diaspora? Dr. Maghbouleh, you mentioned (in part 5) that it was rare for first-generation parents in your research to express an interest in Islam. I can definitely see that being the case in various communities in the diaspora, and I would be interested to learn more about your sampling methods (as well as your view on selection bias in the research). I would also be interested to know if any of the participants were Muslim, and how religion intersected with race in their lives, especially when considering the ways Muslims in general are racialized as non-white. (I’m also interested in learning more about the ways religion intersects with race for participants from other religious backgrounds as well.)

Lastly, I hope Iranians are not doing cost-benefit analyses to determine whether we should identify as white or non-white. Something about that feels off morally, sounds repugnant. I understand the motivations, but if people are spending time and energy only to get ahead of the next racial group instead of working in solidarity towards justice, then something’s wrong.

Marg bar Aryan Myth. Marg bar white supremacy.

[References]

1. Iranian Identity, the ‘Aryan Race’, and Jake Gyllenhaal (by Reza Zia-Ebrahimi)

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2010/08/post-2.html

2. Michigan in Color: I am still sister outsider (by Ciarra Ross)

http://www.michigandaily.com/opinion/michigan-color-i-am-still-sister-outsider

Thanks very much for the comment. I am against white supremacy and critical of white supremacist ideologies and practices in the broader IA community. I argue that Iranians and others from the SWANA region are incorrectly IDed by the state as white and use Zia-Ebrahimi throughout the text as an outstanding example of research that exposes the pervasiveness of Aryan/white supremacist ideology in Iranian national identity. “Median in color” is a typo (median income is what I say in the audio). Appreciate the chance to clarify!

Hi Mojy. Thanks for the insightful comments. In response to your question, I was referencing a common phenomena in Iranian diaspora organizations in the US (and I believe Canada/Europe as well), where Iranian organizations will explicitly say they are a “nonreligious organization.” Often this is meant to create a safe space for all Iranians of various backgrounds and faiths, but sometimes (and I speak anecdotally now) its unintended consequence is that Iranians who do adhere to a particular religion feel marginalized or even stigmatized when they attempt to get involved with the Iranian community. And many times, in my own experiences, I’ve seen “culture” and “religion” be divorced from one another as if they are separate categories, when they are very much historically intertwined. My questions for Prof Maghbouleh were meant to elucidate these episodes for myself and for others in the audience who had similar experiences.