A guest post by Aria Fani. A native of Shiraz, Fani studies towards a Ph.D. in Near Eastern Studies at the University of California in Berkeley.

هشتاد سالگی و عشق؟ تصديق کن که عجيب است

حوّای پیر، دگر بار، گرمِ تعارفِ سيب است

Love at Eighty?

Admit it: it’s bizarre.

Ancient Eve is, once again

offering apples

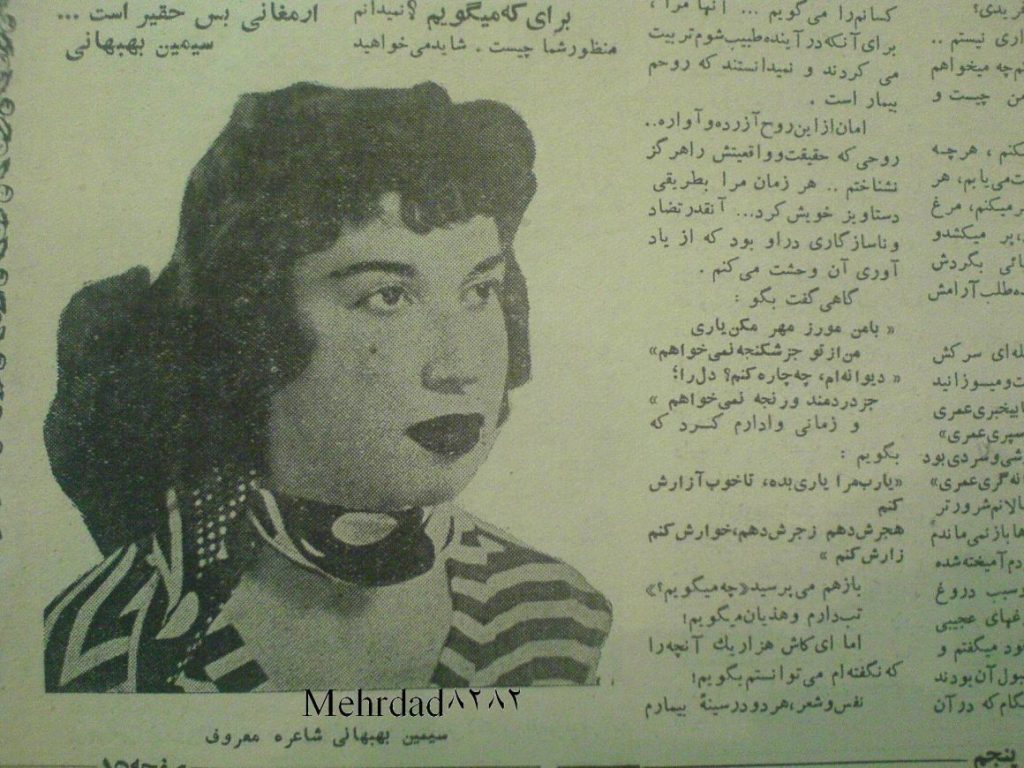

Simin Behbahani, distinguished Persian-language poet, passed away on August 19 in Tehran. Behbahani was a major figure on the Iranian literary landscape whose work enjoyed readership not only in Iran but also in the wider Persianate world. Born in 1927 in Tehran, Behbahani began composing poetry at the age of 14. Having initially experimented with chaharparah and shi‘r-i naw (free verse), from the mid-1970s she turns to the ghazal as the main vehicle for her poetic expression. Like most her literary predecessors, she adds new themes and original meters to the classical form. Unlike many of them, Behbahani does so with much success. One may ask, what factors contribute to her critical acclaim and popularity? The dynamic interaction of what Behbahani–in dialogue with her literary milieu–has conceptualized as old and new, formally and thematically, has led to the composition of ghazals that speak powerfully to multiple realities and emotions.

With over 15 volumes of published works (spanning over 600 poems), Behbahani’s work deals with love, war, peace, revolution, class disparities, gender discrimination, polygamy, marital life, domestic violence, patriotism, prostitution, aging, poverty, and global violence. She has won numerous accolades over the decades; more recently MTV U crowned her Poet Laureate for 2009. A Cup of Sin (1999), Maybe It’s the Messiah (2004), and My Country, I Shall Build You Again (2009) present selections of her verse in English translation.

Since her passing, a host of obituaries has appeared in such reputable venues as The New York Times, The Economist, The Guardian, BBC, NPR, Al Jazeera, and PBS.Writing brief narratives that speak to the multifaceted legacy of Behbahani — poet, writer, educator, and activist — may be beyond the scope of obituary writers unfamiliar with the Persian literary tradition. Obituaries briefly touch upon different aspects of a figure’s life while highlighting their greatest accomplishments. It is particularly bizarre that all the aforementioned papers have opted to frame Behbahani as a national political dissident and situate her poetry exclusively within the context of her social activism, designating her as a standalone figure. There is a deliberate effort to cast Behbahani as a national voice in direct opposition with the Iranian regime, a reductive framework that necessarily occludes the complexity of her verse and reception. Consider the following titles:

“Simin Behbahani: Iran’s most famous female poet and defender of human rights”–Guardian

“Outspoken Iranian Poet, Dies at 87”–New York Times

“the Lioness of Iran”, died on August 19th, aged 87”–Economist

“’Lioness Of Iran,’ Dies At 87”–NPR

“Iran’s national poet, dies at 87”–PBS

“Simin Behbahani: Formidable Iranian poet and fearless activist”–BBC

“Iran’s last great female poet Simin Behbahani, whose poetry was quoted by Barack

Obama, has died aged 87. But her work lives on.”Al Jazeera

Another pattern emerges in these headlines: even as English-language papers define and celebrate Behbahani, they define themselves, their ideological purposes and political dispositions. In other words, Simin Behbahani is used to tell other stories. Some of these stories overlap with her literary and social preoccupations. But mostly, these stories tell us more about their storytellers than the protagonist of their narrative, the deceased poet. Primarily, inserting Behbahani into an “Iranian national canon” ignores her readership and reception in Afghanistan and Tajikistan and frames her work as a national allegory, the voice of an entire nation. Reductive and modern epithets such as “Iran’s national poet” divorces Behbahani from her literary culture, one that has operated across a diverse ethnic and religious territory with permeable frontiers and multiple participants over the course of one millennium.

What does it mean to imagine Persian literature as a “national canon,” a tradition whose history–except the last century–predates the era of flags, borders and passports? Writing “nation” on the body of Persian literature participates in the erasure of dynamic and ongoing conversations on genre, form, and style that have shaped the contours of this literary tradition across a vast geography that in the premodern world stretched from Anatolia to the Bay of Bengal. What does it mean to imagine Persian literature as a “national canon” even today? For instance, Mahmoud Dowlatabadi (b. 1940), often framed as Iran’s national novelist, imbues his prose with distinctly Khurasani expressions and lore. While a glossary is appended to many of his novels for Tehrani (Isfahani, Shirazi, etc) readers unfamiliar with Dowlatabadi’s lexicon, his readers in Kabul, Balkh and Herat are familiar with the novelist’s Khurasani heritage and rarely feel the need to consult a dictionary. The framework of “national literature” has proven inadequate and reductive time and again in the context of literary and cultural studies. Once interrogated and put in conversation with literary history, it fails to accurately reflect the evolution and complexity of a literary tradition as wide-reaching as Persian literature.

The poetry of Simin Behbahani stands on an ongoing conversation with and an acute understanding of the Persianate literary past; it is precisely based on this foundation that Behbahani appropriates, reshapes, and reinterprets the Persian ghazal. I use “Persianate” here– instead of Persian or Iranian–a term coined by the historian Marshall Hodgson (d. 1968). Persianate refers to a cultural expanse that has been cultivated by different participants who may not have been ethnically Persian or inhabitants of the Iranian Plateau, all the same have necessarily shared the distinct elements of Persianate cultural heritage, mainly literary preoccupation with Persian. This narrative serves as a more robust backdrop against which Behbahani’s poetic legacy can be set.

Furthermore, the primitive syntax of “He is the national x of Iran” or “She is the female y of Afghanistan,” a well-known remnant of colonial practices, occludes the protean and permeable nature of Persianate literary culture and confines Behbahani within a “national canon.” Another figure that immediately comes to mind is Forugh Farrokhzad (d. 1967), a poet and filmmaker whose verse has been turned into an arena for obsessive treatments of her sexuality and gender. The work of no other contemporary Persian-language poet has been biographized to the extent Farrokhzad’s oeuvre has been. These practices have been more extensively examined within the context of Persian in South Asia. More recently, Rajeev Kinra (2012) has convincingly demonstrated how European historiographers rewrite Chandar Bhan–a seventeenth-century Persian-language litterateur and state secretary of Mughal India–as a standalone Hindu figure who gained success by virtue of writing in a “foreign” language (Persian) and in spite of his “non-Islamic” (Brahman) faith. Kinra’s scholarship participates in the process of recovering the legacy of Chandar Bhan by placing him in his own historical context, much the same way I suggest that a close examination of Behbahani’s oeuvre will be a great step in the retrieval of an important voice from such colonial framings as “Behbahani, Iran’s national poet” or “Iran’s last great female poet.”

Behbahani was primarily a poet and is remembered by her readers as such. Yet, she is characterized mostly by extra-literary titles: female poet, defender of human rights, Lioness of Iran, Iran’s national poet, and fearless activist. Assigning the qualifier “female poet,” one that Behbahani has never used to refer to herself, reinforces the subclassification of her poetry without giving any insights into how her “femaleness” distinguishes her verse from work by other poets. Behbahani is hailed as a “lioness” for choosing to remain in Iran, resist the Iranian regime’s efforts to restrict her mobility and oppose censorship. Following this background, only two out of seven obituaries fail to mention President Obama’s 2011 Nowruz greetings wherein he criticizes Iran’s human rights record and ends his message by quoting a poem by Behbahani. Such narrative co-opts Behbahani’s voice, in all its diversity and complexity, into an overtly politicized and dehistoricized paradigm. While every obituary quotes Obama so to validate the “universality” of Behbahani’s verse, they all fail to critically examine how Obama attempts to draw validity from a Persian-language poet to color his own policies (i.e. economic sanctions) towards Iran as just and unavoidable.

BBC goes one step further and calls Behbahani “fearless.” A description that raises many questions: would English-language papers call an English or European poet “fearless” ? What if their poetry engages such issues as military occupation, capitalism, or drone attacks? What type of rubric does “fearless” lay out for “female poets” in Iran who choose not to engage socio-political issues, or those whose poetry does not lend itself to a political critique of the Iranian regime? Would English-language media even hear their voices? How would a critical poet who has left Iran be characterized? Fearful yet outspoken? BBC’s designation is downright irresponsible at best and colonial at worst; it erases the complex and protean context wherein Behbahani’s poetry has interacted with the discourse of power in Iran.

To reject any trace of an autobiographical voice in Behbahani’s verse, partially informed by her struggles for civil liberties, would be equally a disservice to her legacy. Nonetheless, such examination will have to consider Behbahani’s entire oeuvre within the context of Persian poetic conventions. Ideological framings of Simin Behbahani by English-language papers function no differently than mechanisms of censorship that defang any given work by uprooting it from its historical context and co-opt it within a politicized framework. The political power of Behbahani’s work does not solely rest on its social critique of this or that government in Tehran, as suggested by these obituaries. It will suffice to say that her refiguration of ghazal’s expressive capacity, in conversation with Persianate literary tradition, is profoundly subversive.

The Behbahanian ghazal is a robust rebellion against a poetics that deemed being modern synonymous with doing away with all that is (perceived as) old. Behbahani puts forth a new poetics, one that in the space of several decades goes from challenging the rhetoric of modernist canon formation to creating a canon of its own. This is a legacy rendered invisible by a language (i.e English media) that forbids nuance and discards ambiguity. It is a language burdened with awe and praise (i.e. fearless, outspoken, great female poet), one that seeks to stabilize the meaning of political poetry solely as critique of state. It is a language that comforts its readers (that there are internal voices critical of the Iranian regime) while it fails to reflect upon its own participation in the erasure of Behbahani’s voice and that of many others. Such trends in the West join in alliance with the very mechanisms of political repression in Iran that set to create a homogenous literary language that does not afford any critique of the state. To indicate how easy it is to fall into such traps, I refer to my own essay, written two years ago, where I characterized Behbahani as Iran’s Lady of Ghazal. These statements need to be engaged and interrogated, whether made by English-language media or Persian-language commentators.

It goes without saying that Behbahani has been widely published in Iran, her poems have been turned into popular songs, and recited in literary circles. Behbahani’s readers know where to find her voice:

آدم! بيا به تماشا، بگذر ز چالش و حاشا

هشتاد ساله حوّا با بيست ساله رقيب است

Adam! Come see the spectacle.

Leave behind your denial and conceits

and watch as the Eve of eighty

rivals the twenty-year-old she.

For those who do not know her, these obituaries only offer a name, one to explore and investigate (see bibliography). Behbahani was one of the most distinguished poets of our time writing in Persian, and English-language papers failed to rise to the occasion and gravely missed the mark on remembering this multifaceted figure. Behbahani, like many women from the so called “third world,” is framed to represent her nation while her most powerful legacy– her literary voice– has been defanged and dehistoricized through series of politicized and extra-literary epithets. Nonetheless, these obituaries–unmistakable symptoms of much broader historiographical patterns–document an illuminating account of dual rubrics informed by ideological convictions rather than the standards of balanced and careful journalism.

This essay was written in dialogue with Leyla Rouhi, Wali Ahmadi, and Sara Salem.

Sources

- Havva-yi pir (Ancient Eve) translated by Adeeba Shahid Talukder and Aria Fani. Previously featured in The Huffington Post.

- Rajeev Kinra (2012). Writing Self, Writing Empire. Internet resource.

Bibliography on Simin Behbahani

- Sharifi, F. (2013). Simin Bihbahani az āghāz tā imrūz shiʻr’hā-yi barguzı̄dah tafsı̄r va taḥlı̄l muvvafaq’tarı̄n shiʻr’hā. Tihran: Pigāh. (Persian)

- Milani, F. (2011). Words, not swords: Iranian women writers and the freedom of movement. Syracuse, N.Y: Syracuse University Press.

- Special issue: Simin Behbahani (2008). Iranian Studies, 41:1.

- Dominic Parviz Brookshaw (2008): Revivification of an Ossified Genre? Simin Behbahani and the Persian Ghazal, Iranian Studies, 41:1, 75-90.

- Dihbāshi, A. (2004). Zanī bā dāmanī-i šiʻr: Jashn-nāmah-i Simin Bihbahani. Tihran: Muʼassasa-i Intišārāt-i Nigāh. (Persian)

- Vizhah-yi Simin Bihbahani (2006/1385). Iran Namah, 23.1-2. (Persian)

- ʻĀbidī, K. (2000). Tarannum-i ghazal: Barʹrasī-i zindagī va ās̲ār-i Simin Bihbahani. Tihrān: Nashr-i Kitāb-i Nādir. (Persian)

- Milani, F. (1992). Veils and words: The emerging voices of Iranian women writers. Syracuse, N.Y: Syracuse University Press.

- Vizhah-yi Simin Bihbahani (1993/1372). Nima-yi digar, 2.1. (Persian)

- Ḥariri, N. (1989). Guft va shunūdī bā Simin Bihbahani, Ḥamīd Muṣaddiq. Babul: Kitābsarā-yi Bābul. (Persian)

Translations

- Mahasti Yazdi and Marianne Larsen (2012). Kærlighed i blodet. Copenhagen. (Danish).

- Khalili, Sara (2009). My Country, I Shall Build You Again: Selected Poems (bilingual edition). Tehran: Sokhan Publications.

- Farzaneh Milani and Kaveh Safa (1999). A Cup of Sin: Selected Poems. Syracuse University Press.

- Bahran Choubine and Judith West (2000). Jenseits von Worten. Essen: Nima-Verl. (German)

- Salami, Ismail (2004). Maybe It’s the Messiah: Selected Poems. Tehran: Abankadeh Publications.

1 comment