Emerging Scholarship is a series showcasing the research and interests of new voices emerging from academia that focus on the social worlds, histories, and traveling cultures of Central and West Asia.

The following is a guest post by Ghazaleh Haghdad Mofrad. Ghazaleh was born in Tehran and migrated to Belgium at the age of nine. Growing up, she had few opportunities to go back to Iran until the age of 20, when feeling nostalgic for Iran. To re-establish ties with her “homeland” and rebuild her Iranian roots, she started a Phd in anthropology on the implications of globalization on young adults in Tehran. Her research interests include the impact of globalization, identity formation, marital strategies, construction of femininity, and female body modifications in Iran.

From the range of Iranian cultural productions, foreign audiences are best acquainted with the few cinematographic works that cross Iran’s borders and enter the international festival scene. It is much less common for foreign tastemakers to show interest in more mainstream and government-sanctioned forms of media production in Iran, or their ongoing transformation over the last few years. Yet the field of cultural production in Iran is in flux. Given the importance that this field represents for the Islamic authorities and the high investment it has received since the 1979 Revolution, any transformation in the arena of the mass media has potentially deep implications and should be the subject of close attention.

A striking example is the recent emergence of an innovative method in the distribution of officially sanctioned cultural content, called the “home show” (namâyesh-e khânegui). These shows have official government permission to be produced, yet are only allowed to be distributed through DVD sales. Though they take the format of television shows, they are not broadcast over official airwaves. The “home show” network has opened an alternative space of expression within the official media landscape of the Islamic Republic (IR), where new cultural content can circulate. This recent development has had a significant impact on the quality and diversity of official productions more generally and has helped, in part, to boost this larger domestic market at a time when it is facing increasing challenges from global media. These changes are clear signs of the dynamism of Iranian society, its potential towards social change, and its innovative ability to develop original solutions that take into account both local constraints and demands as well as global pressures.

The development of the “home show” network

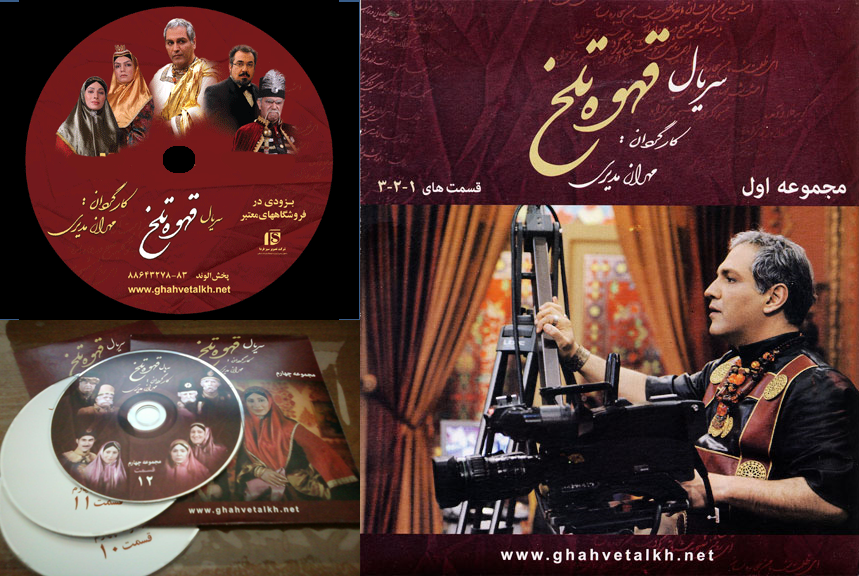

In 2010, famous Iranian actor and director Mehran Modiri produced a historical comedy show entitled “Bitter Coffee” (qahve-ye talkh), designed to be aired on Channel 3 of the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) network. Following a disagreement with IRIB managers – the details of which are still unclear – Modiri took the risky initiative of directly distributing his show to audiences through DVD. Three new episodes of “Bitter Coffee” were thus legally released and sold almost every week in local stores at the price of 2.500 Tomans (approximately US$2.5 at that time).

This move proved to be great a success as Modiri managed to sell 14 million DVDs of his show. This success of his direct-to-DVD approach encouraged other directors to also follow this suit, and contributed to the development the “home show” (namâyesh-e khânegui): a unique network of distribution serving as a support for officially vetted productions intended to be watched within the private sphere of the home.

The “home show” network constitutes an alternative form of media distribution – which also engenders an alternative form of cultural production – entirely specific to the Iranian context, and allowed the opening of a new space in the official media landscape of Iran. This network also has the advantage of meeting the increasing demands of a society which is in a rapid process of transformation and highly exposed to globalization, that has not yet, however, touched the official surface of the IR. In this regard, it clearly illustrates the dynamism and the creativity that exist in cultural productions and it is an excellent example of the way the local and the global are being negotiated in the IR. In order to better understand the major challenges of the emergence of such phenomenon and its potential meaning and novelty, one needs to understand the larger audiovisual media options available in Iran in order to see how this format comes to graft itself into the existing landscape.

IRIB and cinema versus satellite TV and illegal DVDs

Besides “home shows”, there are four major forms of audiovisual media options in Iran. Two are official and largely produced in the country: IRIB productions and cinema works. Two are illegal and mainly produced abroad, essentially in the West: the satellite TV programs and the illegal DVD market of Western shows (movies, shows, serials, etc.). The Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) is the institution in charge of the entire radio and television productions of the country. It is under the direct control of the supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, and constitutes the official face of the IR. It broadcasts shows whose contents reflect essentially the visions of the most conservative fringes of the IR. This does not mean, however, that there has been no form of evolution in IRIB offerings.

In recent years, the IRIB has significantly transformed and increased the number of channels and productions it offers. These transformations were developed in order to meet the increasing demands of the population in entrainment and youth programs. Despite this quantitative development, the IRIB has always remained in the hands of a limited group of people close to the supreme leader and faithful to his ideals, who have controlled and limited severely the content and form of its productions. This stranglehold has affected the quality and diversity of IRIB offers, which have been overall quite low.

It is thus cinema which, in Iran, has made some room available for dissident voices and enabled the production and diffusion of richer and more diversified cultural works. This can be explained by the fact that, unlike the IRIB, cinema has never been under the direct control of the supreme leader but is instead dependent on the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (MCIG) managed by the government. Changes in the leadership of this organ and the important role it plays within the political arena have occasionally worked in favor of cinema, enabling a relatively large space in which Iranian artists can negotiate and maneuver. Moreover, as Sayeed Zeydabadi-Nejad (2010) has convincingly shown in his study of cinema politics, interpretation, and compromise between directors and regulators over the rules imposed on cinematographic works have opened a space that has made possible the release of innovative and quality films.

These two official media options compete with two other forms of cultural sources that are both technically illegal but very widespread in Iran: satellite TV and DVDs of Western television shows. It was in the early 1990s that Iranians started using dishes to access other types of programs than those provided by IRIB. At that time, the offerings were very limited and there were no Farsi-speaking channels available. But things have dramatically changed over the past years with the vast increase in the number of Farsi channels and shows on satellite offer.

As a response to this so-called “invasion,” authorities immediately took some measures in 1995 to ban the use or trade of satellite equipment and crackdowns have been regularly organized since in order to remove dishes and punish their owners. More recently, another way of fighting satellite TV content has been the use of static noise in politically sensitive times to disturb the information broadcast by Western-based news channels such as BBC Persian or Voice of America Persian.

In reality, however, the use of satellite TV has become largely widespread in Iran and has almost become normalized to the extent that its use, even among Iranian state officials, is often referred to in the media. Most interestingly, some satellite TV channels now play music that is both legally and illegally produced in Iran, blurring the limits between the official and the illicit and between local and foreign-based productions. Finally, the fourth channel through which cultural materials are distributed are illegal DVDs. These are the successors of video-cassettes whose emergence dates back to the 1980s. Like alcohol, illegal DVDs are available almost everywhere in Iran and each family usually has its own appointed dealer.

It is within this broader media landscape, where official and semi-official channels fiercely compete, that home shows have appeared as a form of compromise between the local and the global. Without staining or threatening the official face of the IR, the home show network gives Iranians the possibility of accessing alternative materials of entertainment comparable to what is offered by satellite TV (especially reality shows!) or illegal DVDs but in an Iranian and Islamic style. By leaving the state-broadcasted distribution format, home shows have left the notoriously constraining frame of the IRIB to go under the looser structure of the MCIG. This move from television to DVD has made possible the productions of television-type programs within the space of freedom that was so far only allocated to cinema.

This exit of TV shows from television has had an important impact on the quality and the diversity of what is being produced in the cultural and entertainment field. Home shows are very different from IRIB productions in their content and their form. In these shows, the rules of hejâb are less scrupulously observed, women are presented in more realistic and powerful ways, the spectrum of the themes dealt with is much larger and finally, and the approaches to sensitive topics are more nuanced.

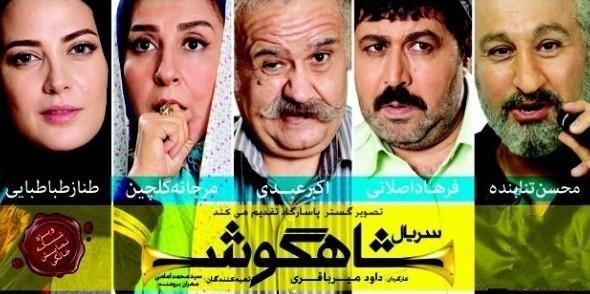

The recent home show “Shâhgoosh” (2014), directed by Davood Mirbaqeri and casting major actors of contemporary Iranian cinema is an excellent illustration of that. In a stunning way, this 28 episodes-long comedy challenges the boundaries of censorship and openly discusses some of the most sensitive illnesses of contemporary Iranian society and policy. Moreover, it does it in a joyful and colorful set that is in total contrast with the lugubrious and depressing atmosphere of IRIB programs.

Providing a much more diversified and attractive offer, home shows have also managed to re-attract the attention of Iranians towards local productions and compete seriously with satellite TV and illegal DVDs. Their emergence has thus emerged to meet a strong local demand for alternative forms of entertainment and fill a gap in the official media production. Their impact on the local market is not, however, univocal given that they have been reported as a potential threat to the Iranian cinema industry in the future.

Conclusion

Many things could still be said and clarified about the conditions in which the home show network has developed in Iran. The objective of this paper is simply to draw attention to a transformation within cultural politics in Iran that has been completely ignored in the West while it has important meanings and impacts. These are the following: 1) the dynamism that exists within Iranian society and the inherent potential it has towards social change 2) the fact that Iran, far from living in a cultural isolation, participates into the larger wave of globalization. The development of this medium shows that initiatives and pressure from below have the ability to change the political situation of the country. In a similar way, home shows’ new content points to globalization and the way Iran takes part to it in its own innovative and Islamic way.