Ajam Media Collective is proud to launch its first ever digital book club, featuring Sohail Daulatzai’s Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Black Freedom Beyond America.

Mark your calendars–we will be hosting live-streamed conversations with the author on the following date:

Sunday, April 5th at 12pm PST: Discussing Chapters 4 and 5, Conclusion

To catch up on Chapters 1 and 2, check out the discussion by Omar Kamran, and our recording of the live-streamed discussion with Sohail Daulatzai. For Chapter 3, read Rasul Miller’s discussion post and listen to our recorded discussion.

Prior to each live-streamed conversation, we’ve invited an outside reader to comment on the chapter readings for that week. This week, Samiha Rahman sent us her comments with some questions to get our discussion started.

Samiha Rahman is a PhD student in Education and Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research interests include race, religion, political activism, and education for liberation amongst communities of color globally. Prior to entering graduate school, Samiha worked with middle- and high school-aged youth of color in Philadelphia and New York City in the field of youth development — particularly with leadership and social justice education.

***

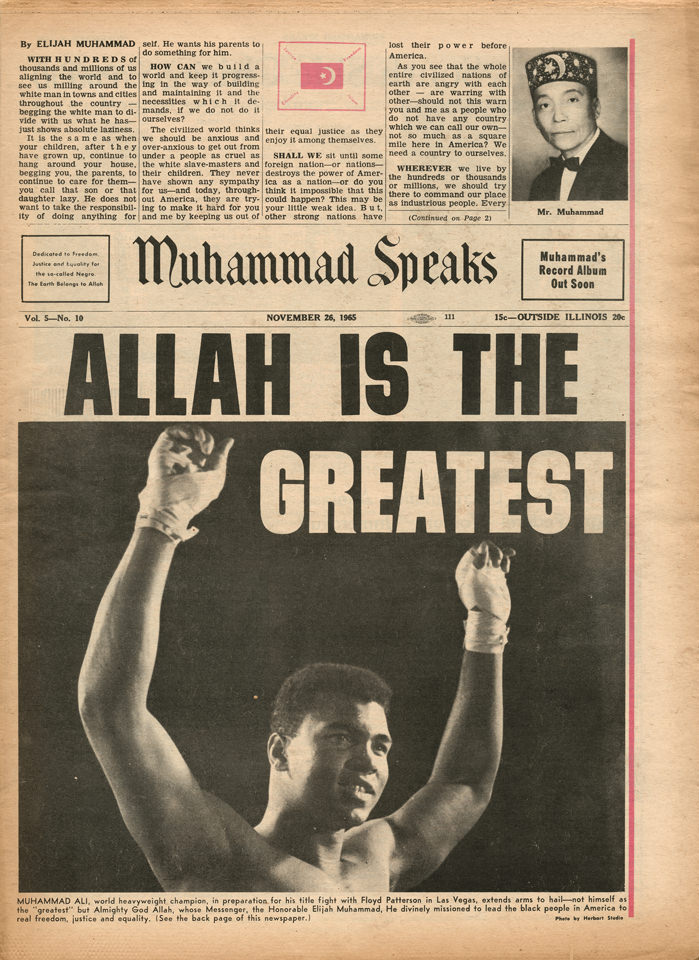

In the fourth chapter of Black Star, Crescent Moon, Sohail Daulatzai explores Muhammad Ali’s legacy and impact in popular culture and politics in the United States. Unlike Malcolm X, whose political, intellectual, and spiritual development was cut short due to his untimely martyrdom, Muhammad Ali has continued to grow in the decades since X’s death. Though both Ali and X once voiced radical critiques of racism and imperialism, Daulatzai argues that Ali is now seen and celebrated as a sanitized U.S. national hero. Daulatzai cites a documentary (the depoliticized When We Were Kings) the national awards and invitations he received from the last three U.S. presidents, and other instances to show how Ali’s legacy has changed over time.

Daulatzai’s analysis of Ali’s legacy centers around the question, “Would Ali be as revered as he is today if he were still able to articulate his thoughts and feelings the way that only Ali knew how?” (141). In 1967, when Ali pointed out the United States’ hypocrisy in fighting for freedom internationally while brutalizing Black Americans domestically, his opinions were met with resistance from the government.

By openly and forcefully voicing his criticism of the Vietnam War and refusing to serve in the armed forces, Ali was stripped of his heavyweight championship and faced a five-year prison sentence. More recently, as Ali has become muted by illness, he has been celebrated as a national hero. In 2005, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush, and in 2009, he was a guest of honor at an inauguration party for Barack Obama. If Ali criticized police brutality and the state-sanctioned violence against Black and Brown communities in the U.S. today, what would the consequences be?

One easy way to attempt to explain Ali’s shift over the years would be to debate whether he consciously and strategically withholds his political views for political gain. Another way would be to speculate about how his age and illness have contributed to his de-radicalization over the years. However, there are several more difficult yet perhaps more important questions to ask. First, to what extent is Ali’s evolution symbolic of the popularity and comfort of a linear narrative of racial progress, one in which attitudes of color-blind racism and post-race rhetoric flourish?

To this point, Daulatzai notes the popular narrative around Ali that “because of his courage, America is now a better place, able to transcend the limits that its own racism once imposed upon it” (166). Second, to what extent has the space for public political critique narrowed, or has the notion of such critique been transformed? For example, in professional sports, the positions many athletes take in response to racial injustice today are strikingly different from the positions Muhammad Ali took during the 1960’s. Third, should we hold our public leaders accountable, and to what extent are they expected to fulfill our expectations? Answering these questions may help extract applicable lessons from Ali’s legacy.

In chapter five, Daulatzai highlights the administrative and institutional connections between U.S. prisons domestically and internationally. Many of the same military personnel who regulate prisons in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Guantánamo Bay come back to staff or train prison guards in the U.S., a trend that is indicative of the growing militarization of domestic police departments.

Similarly, top prison officials in the U.S. – many of whom have been accused of human rights abuses against prisoners domestically, as Daulatzai cites – export their experiences and practices to facilities such as Abu Ghraib and Bagram.

Daulatzai’s arguments demonstrate the global interconnections amongst law enforcement practices, a reality seen with reports that the chief of the St. Louis County Police department received counter-terrorism training from the Israeli Defense Forces and reports that a U.S. company manufactured tear gas canisters used by law enforcement officials in both Ferguson, Missouri and in Gaza, Palestine. These connections help contribute to the reality that the same logic that criminalizes and dehumanizes Black and Brown communities in the US motivates the imprisonment of and policies against Muslims abroad.

Daulatzai also argues that the post-9/11 era has resulted in the collapse of the categories of “Black criminal” and the “Muslim terrorist.” One example is the imprisonment of Imam Jamil Al-Amin – formerly known as H. Rap Brown, who was a leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panther Party – and his portrayal as a “homegrown terrorist.” Daulatzai also cites the Department of Justice, FBI, and Homeland Security rhetoric of “Jailhouse Islam” and their broader fears of Black Muslims becoming radicalized in prison.

Given the rich history of Islam in U.S. prisons, in particular the transformative effect the Nation of Islam had on Malcolm X during his time in prison, what are the practical ramifications of these federal and state fears?

Given the rich history of Islam in U.S. prisons, in particular the transformative effect the Nation of Islam had on Malcolm X during his time in prison, what are the practical ramifications of these federal and state fears?

What does this mean for Muslim chaplains working in prisons? What does this mean for individuals who embody the radical spirit of the Muslim International and provide services to imprisoned people? What constraints do they face, and what opportunities exist to challenge these constraints?

In the epilogue, Daulatzai’s writings become prescriptive. He critiques the Muslim-American identity, arguing that the embrace of such a label and the related “desire to be a ‘good citizen’ and achieve ‘honorary whiteness’ ultimately conforms to a dangerous and dubious model of liberal multiculturalism, ‘diversity’ and anti-Blackness” (194). It is important to note that Daulatzai directs these warnings towards immigrants, particularly those from the Muslim Third World – and likely those from the non-Black Muslim Third World.

He does not discuss why the Muslim International may also be meaningful and important for non-immigrants (who are also, presumably, non-Black). The alternative that he recommends – the Muslim International – enables Muslims living in the U.S. a means of forging the types of global connections and coalitions, as well as anti-racist, anti-imperialist critiques that Malcolm X and others formed decades before.

Given the palpable presence of anti-Blackness in many non-Black immigrant Muslim communities in the United States, Daulatzai’s Muslim International framework encourages people to understand and challenge the divide and conquer strategies that not only sustain white supremacy but also fuel anti-Black racism in these communities.

While Daulatzai’s Muslim International certainly holds promise, one question remains unanswered: if a Muslim International sensibility is intended to serve as an alternative to a Muslim American identity, is Daulatzai’s audience implicitly limited to Muslim Americans? In other words, to what extent is his Muslim International actually a Muslim American International?

1 comment