The following is a guest post by Sarover Zaidi. Zaidi studied philosophy and social anthropology at St. Stephen’s College and Delhi School of Economics, Delhi University. In the last ten years, she has lived in a Buddhist nunnery, worked in a bank, attempted to learn pottery, worked across rural India on women’s health, public health and medicine. She tweets @bombaywalee

Her current work relates to architecture, material cultures, religion, and urban studies, all of which she gathers with obsessive fervor between different cities and worlds.

As you walk through the so-called ‘native town’ of Bombay neatly tucked under the JJ flyover bridge, you come across what architects have come to classify as vernacular architecture. The term has come to signify any building built incrementally, locally, without authorship of an architect, and also without the purity of a single style.

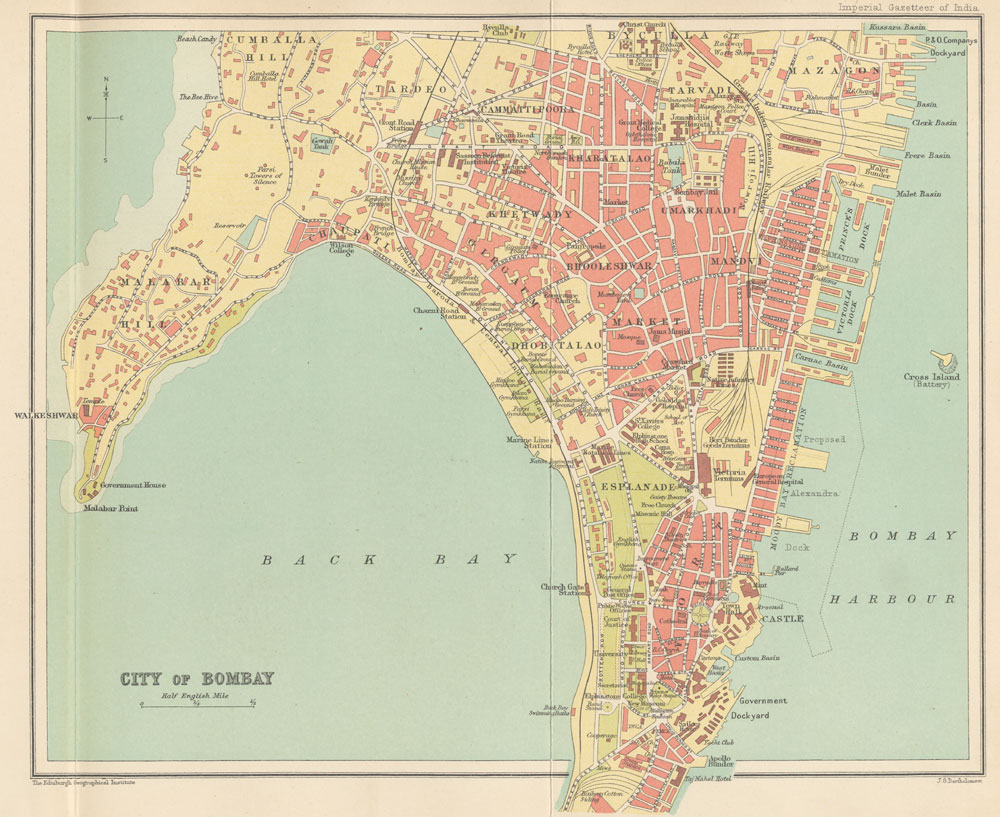

The ‘native town’ was named as such by the British, who considered the area north of the Victoria Railway Station (now known as Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus) to be dirty, disorganized, old and full of natives. Toward the south end was the colonial town of Bombay, which was built predominantly by the British and came to be the symbol of colonial elegance and prestige.

This area – spread across Fort, Kala Ghoda, and Colaba neighborhoods – today bourgeons with high-end restaurants, cafes and shops catering tothe gentrified indulgences of elites, tourists and others clinging to a nostalgic vision of Bombay’s colonial past.

To the north of Victoria Station are the colonial town’s poorer – but equally ancient – neighbors. Nowadays, the ‘native town’ is tucked under the JJ overpass, the bridge asserting a clear vertical sovereignty that allows those heading to the colonial town from the rest of Bombay to hop right over the congested and dilapidated neighbourhoods of Bhendi Bazaar, Dongri, Umerkhadi, Nagpada and Pydhonie.

The result is the homogenization of a vibrant and heterogeneous area below, transforming it into a ‘ghetto’ in the popular imagination. But to accept such a designation would be a terrible mistake. While the colonial city is considered the heart of the cosmopolitan colonial past, it is in the native city that where a rich variety of architectural styles reflecting the far more diverse history of the area can be more readily seen.

One building, for example, integrates a mélange of architectural styles, facades, and eras. Utterly different from the planned facades of the British colonial city, it is instead adorned with blue painted Greek pillars, embedded alongside baroque ornaments, Rajasthani jali balconies, and Mughal ornamental flowers, the whole thing running six stories high with patchwork concrete and art deco rims.

Who imagined all of these features together and where and how did such diverse styles seep into the built form of this part of town so often dismissed as dilapidated and congested? Where did the money come from, who were the masons, where did they find these designs and how did they translate them into the local?

The question “Who is the architect?” is a question that repeatedly comes to mind when thinking about these buildings, resonating most closely with the rise of individualism expressed most lucidly in Michel Foucault’s 1969 article “What is an author?” Foucault attempted to explain an aspect of modernity which compels in its presentation a singular vision on language, writing and authorship.

In doing so, it erases or underplays the dialogical histories, conversations, and readings which the author would have been part of in developing his/her ideas, skills, and styles of writing his or her book. In a similar vein, when we over-subscribe to the architectural vision – and the notion of individual authorship it depends on – we erase histories of masonry and trade as well as the localising and globalising aesthetics and community visions of its existences and its futures.

The manners in which craftsmen work with the materials available, or engineers grapple with the underground water tables of the city, or masons integrate designs flowing in from across the world and weave them into what is possible in local materials alongside what already exists as an archive in their handwork, becomes hidden under the concrete facades of architectural individuations so replete in modernity.

These areas withhold a differential kind of planning, use and execution that grows slowly through availability of resources, needs, working together with multiple visions and skills. The history of this area is severely under-recorded, not available as an easily-accessible written archive. The archive instead unfolds before us, through the presence of buildings, arcades, facades, providing us the most creative, coherent and material evidence of a dynamic and diverse past of the city of Bombay.

Of cosmopolitans and citizens

The cosmopolitan history of Bombay is generally centered around south Bombay, or the colonial city. The ‘native town’, then, becomes doubly invisible and inaccessible as a result of the bridge running vertically over this old area, removing access to its everyday and its congestion for the many who use it to pass through, grafting a speeding horizon atop it. Now mostly accessed as a fetish object of ‘Muslim food’ during Ramadan or for an antique commodity fetishism of the traditional ‘Chor bazaar’ market, the ‘native town’ contests its clichés, simultaneously inhabiting them, too.

Although both of these are intrinsically important aspects of the old town, they have come to define it in an over-deterministic manner the rest of the city’s imagination of this area. The colonial city on the other hand is associated with a clean cosmopolitanism, a clear and customized citizenship, with English literature festivals, organized public spaces and ‘enlightened’ individuals, who walk through the enclaves set up between the colonial era buildings of the British, the Parsis, and the Jews – all of whom represented the era’s elite.

‘Good drains make for good citizens,’ a sentence I often heard after the 2005 floods in Bombay. During the floods, most parts of the Bombay suburbs went down in flooding, but the colonial city was left unscathed by the flood waters. This disdain for other parts of Bombay is not new. Rajnarayan Chandavarkar, one of Bombay’s most critical historiographers, dates the British obsession with control of sewers and sewer flows in the native city to the Bombay plague of 1891 that killed thousands.

Proper citizenship aligned with planned towns, adequate infrastructure and consistent architectural styles and built environments. On the other hand, many parts of the city, especially areas such as the ‘native town’, were declared “problem areas,” a term which increasingly became synonymous in post-Independence Bombay as “areas with large Muslim populations.” Metonymically set on a chain of signification in the imagination of the state, the Muslim became the outsider, the rioter, the terrorist, and the Pakistani, creating a situation in which these areas have fewer state facilities, an overwhelming sense of surveillance, and intensive avoidance by other segments of the population. Class affiliations went in parallel with religious affiliations, creating both real and imagined questions of citizenship, city plans, city control and surveillance for those who resided in these areas.

The Victoria Terminus station located at the cusp of the colonial city and the native city functions as a watershed between the two areas. The forms of everyday living, congestion, housing, aesthetics, kinship and religiosity change as one moves to the other side toward the neighborhood of Byculla. Built more than a hundred years ago, the station functions as an aesthetic sieve of colonial gothic architectural forms and symbols, mixing with Mughal and other Indian formats and aesthetics. Termed popularly as Indo-Saracenic architectural style, the Victoria Terminus station gives us the best evidence of the possibilities of architectural mash-ups in terms of design, materials, architects, draftsmen, and masons.

The area past the station continues this trend but is rarely acknowledged as doing so. The cosmopolitanism of the built environment of the Mohammad Ali road area beneath the JJ flyover from the 1850s onwards has come to be dominated by its supposed contrast with the colonial city. The frame of this cosmopolitanism was set not in the colonial nomenclatures of insular facades, didactic planning, and a subtle yet dominant embedding of Christian and Jewish religious structures, but settled more heterogeneously and incrementally by Muslim and Hindu trading and working classes.

As a result, its cosmopolitanism is often erased and forgotten, the diverse and richly varied working class lifeworlds that met here and built new visions of architecture and identity reduced to a mere dirty sideshow to the main colonial attractions nearby.

An interlaced horizon

The old town resists a singularity of classification and even today appears as an interlaced horizon of architectural styles and facades, traversing eras, designs, use, materials, communities, regions, and religious denominations.

The presence of such density of form and content emerges from the area’s history as a trading zone, with influences coming from innumerable trading communities from the Indian ocean trade routes of East Africa, Iran, Yemen, Gujarat, and other regions of India like Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. The difference of styles here are a material representation of the area’s transcultural histories.

Architectural patronage and this specific bricolage motif of the old city emerged from an ‘Indian ocean moment’ in Bombay in the 19th century, generated by a varied milieu of forms and facades brought in by travelling merchants, artisans, rulers, religious sects, masons and craftsmen.

The 19th-20th century trader was able to carry with him imaginations and aesthetics generating a zone of Indian Ocean design and aesthetics, the material evidence of which holds itself clearly in the buildings in Dongri, Bhendi Bazaar, and Mohammad Ali Road. The diversity of styles and forms of space manifested in the gothic facades, Sufi shrines, jamaat khanas (Muslim community halls), clock towers and mosques, all emerging from either singular or cross-patronage of different groups residing here claiming their right to the city.

Innumerable religious trusts, narratives of Sufi miracles, and public processions all emerged to produce a conflicted yet assertive religious topography in this newly developing city.

Nile Green, in his book entitled Bombay Islam, argues that Bombay was essentially a “Muslim metropolis,” built equally by traders coming from India, from Persian- and Arabic-speaking countries, and from East Africa. His work is a strong challenge to the discourse of the creation of the city as an entirely colonial enterprise.

Iranian traders, the Ismaili Agha Khan and Memons (Sunni traders of Gujarati origin settled across the Indian Ocean periphery) traders from Gujarat introduced newer forms of architecture to the area through their patronage of religious buildings.

The Mughal Masjid built in 1853 utilized the turquoise blue Iranian architecture style, while the Agha Khan introduced the Indo-Saracenic style to the area through the clock towers of the Ismaili Jamaat Khana. A rich Memon trader brought in Rajasthani Haveli facades in combination with gothic facades to the Musafir Khana, established in the early 1900s for Hajj Pilgrims.

Contesting and compliant facades

For the colonial regime, it was the uniform urban façade that gave the area coherence, whereas for the religious groups in this area, it was the presence of their community halls, their mosques, and their homes that provided a sense of structural coherence to their neighborhoods (mohalla). All of these spatial enterprises helped new migrants claim place in the city, fraught themselves with the anxieties of not belonging. It also provided them material markers to show community strength, kinship, and their permanence in the city in addition to opportunities to display money, power and honor.

The public sphere here came to be linked to kinship, religion and exclusivity, all of which were continuously contested through the presence of the innumerable tea shops, shrines and of course the markets.

Mixing of different religious communities – from the Bene Israel Jews, the innumerable Muslim communities, and other classes unfolded in the public spaces of the Irani cafés – restaurants owned by Parsis serving a varied clientele – and through the enclosures of shrines and mosques. Even today, the public sphere of this area moves in waves through the day, with people using the Pedro Shah shrine at Victoria Terminus as a resting space, the small Irani tea cafes for leisure, and the permanent and temporary market spaces for shopping and recreation.

We must imagine 19th and 20th century traders as building their own visions of architecture in dialogue with each other, and not just as individuals aping or mimicking British colonial formats of existence, style and form.

Caught in a nostalgia that constantly, if somewhat secretly, eulogizes the loss of the “colonial” as a form of life, the city today approaches the ‘native town’ with scorn and disdain, an un-civic zone of congestion and tenacious citizenships. In doing so, it forgets to see the aspects of architectural cosmopolitanism that the area has come to provide for Bombay from time immemorial.

1 comment