The following is a guest post by Maziar Shirazi, a family physician based in Solano County, California.

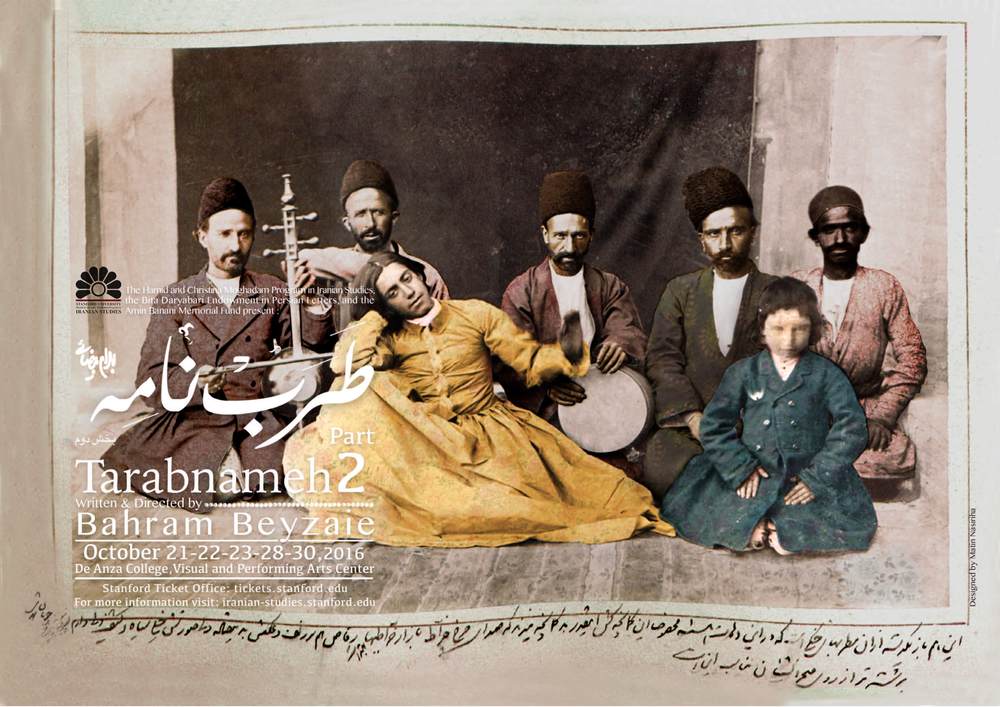

I recently saw Tarabnameh Part 2, the second installment of a massive play by renowned Iranian playwright and filmmaker Bahram Beyzaie in San Jose, where it completed a well-attended run in late October. Tarabnameh is presented as a modern take on a traditional Iranian performance called takht-e howzi or ru-howzi, literally ‘upon the pool,’ as early iterations placed a wooden platform over fountains found in the courtyards of Iranian family homes. This form of theater, traditionally associated with the Qajar period, integrated elements of music, dance, comedy, and storytelling into performances that began in the evening and last all night long. Tarabnameh itself is a two part play over 8 hours in length, and was performed in a theater for a Silicon Valley/Bay Area audience paying around $144 for the whole production.

Expecting a tour de force of contemporary Iranian theater, I was unprepared when I found myself sitting through nearly six hours of racist minstrel show antics. Tarabnameh relies heavily on siyah-bazi (literally, ‘playing Black’), an Iranian theater tradition that features a blackface character performing the role of a servant or slave, usually opposite his master. As baffling as it may sound, this form of modern blackface made it to the Stanford stage in 2016 and was well attended throughout its run by the Iranian community of Northern California.

It was no less disconcerting to see this work coming from an artist acknowledged in the Iranian community for his race-consciousness. Director Beyzaie is an acclaimed filmmaker and playwright who won recognition for his treatment of complex social and cultural issues through his work, including race. His 1989 film ‘Bashu’, was lauded for its portrayal of Afro-Iranian identity and racism present within Iran during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1989), and is considered by some to be one of the best Iranian films of all time.

In a time when institutionalized racism and police brutality against Black Americans are a matter of widespread national protest and debate, what does it mean that Iranian-American audiences are laughing at a blackface performance put on by a supposedly race-conscious director?

Beyzaie’s labyrinthine play begins with a nod to Iran’s history of slavery: a Haji (an honorific for a man who has completed pilgrimage to Mecca) wishes to sell his young Black male slave, named Mobarak, and replace him with a pretty young girl, Nobar, herself recently sold into slavery by her evil stepfather. The name of the more prominent blackface character – Mobarak (‘Blessed’) – is commonly used for the blackface character in siyah-bazi plays. Nobar’s lover, Niavash – neither of whom are black – informs the Haji’s wife of the scheme, and the story unfolds from here. In a subplot, Mobarak hopes to win over Golzar (also called Tohfe or ‘Gift’, an ironic acknowledgment of her being stolen as a child into slavery), another Black slave in the possession of Nobar’s slave trader. The lives of these younger characters and their struggles for freedom and love play a central role in Tarabnameh, amongst other characters, including kings, dervishes, villains and more.

Beyzaie and others have presented siyah-bazi in an appealing light. In a BBC Persian documentary by Maryam Khakipour, for example, siyah-bazi actors discussed the audience’s identification with the blackface character as the performance’s appeal, specifically for his willingness to speak his mind – without the tact expected of other members of society – to figures of authority.

The problems of parodying Blackness, or making it synonymous with servitude, of course, are not dealt with in this discussion, nor in Beyzaie’s own remarks. In interviews available on YouTube, Beyzaie has explicitly denied that the use of blackface in his play is in any way racist, justifying his use by pointing to positive representations of Blackness in Iranian and Indian mythology. In the English language playbill, he describes Mobarak as the hero: the “Black-faced slave” is apparently the archetypal “young king-paladin” in conflict with the evil incumbent king, who is identified with the Haji character. Beyzaie’s assertion is misleading, as siyah-bazi characters – including those in his play – are presented as Black slaves, not heroes or gods, and their representation plays on Black stereotypes. In reality, Tarabnameh perpetuates the problematic tradition of siyah-bazi and, rather than subvert or question the racism that the tradition holds within itself, instead depends upon it.

Those who defend siyah-bazi and Beyzaie’s use of it would point to the dynamic between the Haji and Mobarak as proof of Mobarak’s ‘positive’ qualities. The duo perform a routine common to siyah-bazi productions: the master tries to assert his superiority through obliging his slave to validate his self-image, yet receives only jokes, mockery, and trickery from Mobarak, who “punches up” against his master and the elite stratum of society that he represents. Yet it is clear throughout the play that Mobarak’s role, while conforming to a heroic story arc, primarily serves the purpose of (racialized) comic relief.

In contrast, Niavash, his non-black counterpart, adheres to a more recognizable heroic depiction. At best, Mobarak is a hero in a narrow technical sense, and not in the clear way in which Niavash and or other non-black characters are portrayed.

Similarly for Golzar, her non-Black counterpart, Nobar, plays a decidedly more dramatic and serious role, while Golzar mainly provides laughs with her crude voice and wit. Golzar and Mobarak’s blackness is inseparable from their crudeness and inherent function as characters for the audience not only to laugh with, but also – far too often – to laugh at.

Towards the end of the play, there is a discussion of names that the key characters used to have as children. It turns out that Mobarak’s childhood name was “Antar”: ‘Monkey.’ Referring to her blackface beloved, Golzar quips in Persian, “The name fits him, doesn’t it?” To their credit, not everyone in the audience laughed at this ‘joke’.

As if this wasn’t enough crass racism for the audience’s enjoyment, there was still another helping: Nobar’s old name was Zulbiya, which is a traditional Iranian pastry. Upon hearing this, a character jokes: “Watch out! Antar may eat you!”, in a reference to uninhibited sexuality – a common racist stereotype – attributed not to Nobar’s non-black lover, Niavash, but to Mobarak, the Black slave. These statements were not challenged then or anywhere else in the play. They were, in fact, consistent with its representation and use of race throughout the production.

The ‘race’ problem with Tarabnameh is not simply one of representation–its failure to portray blackface characters heroically–but rather its reliance on the racist tropes inherent in siyah-bazi, which are exploited for ‘comedic’ effect. If Mobarak was wearing a coat jacket and top hat and speaking English, he could have been lifted straight out of a turn-of-the-century American minstrel show. Iranian siyah-bazi, which dates at least as far as the nineteenth century, shares key similarities with American blackface minstrelsy: caricatured Black stereotypes, political and/or social commentary of different stripes, slapstick comedy, wordplay, the use of innuendo, and a degree of direct engagement with the audience. All of these characteristics are present in Tarabnameh’s siyah-bazi performance.

Some would argue that Iranian and American blackface performances are not comparable, but there are fundamental parallels between siyah-bazi and blackface minstrelsy in the US. Looking at Mobarak, for example, the character’s physical movements are recognizable as standard racialized physical comedy, with wildly swinging legs and elbows, butt sticking out, and lips cartoonishly puckered and pulled this way and that, often opposite the direction of his gaze. Meanwhile, Golzar wears blackface with red lipstick, lending a clownish appearance again evocative of infamous American minstrel show imagery. It’s also notable that, more so than the other characters – including the soldiers who rape one of the female characters – Mobarak repeatedly lays his hands on his love interest’s body, demonstrating a sexual licentiousness not displayed, for example, by the play’s non-Black characters.

It is difficult to understate the significance of fact that Tarabnameh trotted out its Iranian blackface performance in the United States, a country with its own deeply entrenched history of racism-driven entertainment. Performed in front of enthusiastic, primarily white audiences from the antebellum period through the first half of the 20th century, the same Black stereotypes we see in siyah-bazi were often deployed to justify slavery (and post-slavery de jure discrimination) through brutally racist portrayals of Black people. The use of blackface and the tropes developed in minstrel shows, such as unrestrained Black sexuality, were integral to the storyline of ‘The Birth of a Nation’, a film later used as a recruiting tool for the Ku Klux Klan in the South. The film – and the entire American blackface minstrelsy tradition – represents a symbiosis of commercial mass entertainment with structural oppression and exploitation, and preceded the now worldwide industry of profit extraction from African-American cultural expressions and representations.

These unfortunate realities are pointed out not with the goal of trying to tear down Tarabnameh, which, in addition to its bewilderingly oblivious racism, is ambitious in other ways. There was certainly much to appreciate in the innovative uses of singing and percussion in various scenes, the simple yet illustrative costumes and set design, and some of the wordplay. It’s also admirable that Beyzaie attempted to resurrect and elevate a form of theater that, within its own historical context, was ultimately marginalized (along with the takht-e howzi actors who also lived at the margins of Iranian society) in favor of European-influenced stage theater. Tarabnameh explored issues of gender, class, and slavery with varying levels of success, and so it feels unfortunate that a play written, produced and acted with considerable effort by a grand mix of established Iranian artists and newcomers has such a massive blind spot when it comes to race.

Ultimately, there are important lessons in Tarabnameh’s successes and failures: first and foremost among these is that siyah-bazi, with its history in the actual enslavement of Africans in Iran and parody of Blackness, is racist. It’s evident that Beyzaie and his troupe missed a clear opportunity to reflect on racial representation, break with the siyah-bazi tradition, and deal critically with the legacy of the East African slave trade in Iran.

At a time when political movements organized around confronting racism and xenophobia in the US have come to the fore of civic society, these tone-deaf depictions register as clearly anti-Black. Insisting otherwise ultimately rests on the assumption that Iranians in the US (largely excluding Iranians of African ancestry) don’t need to consider other communities, racially or otherwise. This attitude is provincial, dehumanizing and a nonstarter for any meaningful solidarity with other Black and Brown communities, a vital project for Iranians – who are also vulnerable to many of the same political mobilizations operating against these communities – to continue developing for our social and political future in this country.

Mr. Beyzaie, a filmmaker recognized for his race-consciousness by many Iranians, produced this play with the passionate support of a large crew of mostly young Iranians and Iranian-Americans, for successful consumption by an audience drawn from one of the most highly educated and politically liberal areas in the entire United States. The issues point not to a guilty individual, but rather to a community collectively in need of serious reflection and self-criticism. Developing the capacity to deal with and grow from these types of experiences depends on our ability to identify and constructively confront racism and other forms of prejudice within our own communities.

Our resources are rich in this regard: many Iranians, across generations, are intimately familiar with manifestations of oppression in myriad forms including colonialism, imperialism, chauvinistic nationalism, religious, ethnic and political persecution, anti-Iranian racism, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, Islamophobia, white supremacy, anti-Blackness, ad infinitum. In this process, it is critical to remember that one may be a victim and/or opponent of racism or other forms of oppression, and also be implicated in perpetuating these very processes upon others.

After the play, exhausted and hungry, we drove home from San Jose, a car-full of Iranian people who collectively have been racialized and discriminated against in multiple countries and contexts over the course of our lives. We discussed Tarabnameh and its vivid racist imagery, which had left the most durable impression of the whole production.

One of our friends from southern Iran told us that her late father once recounted to her that even after the outlawing of slavery in Iran in 1929, African children were still trafficked to the south and, among other uses, gifted as servants to wealthy women entering the households of their new husbands. To identify the presence of such children in the holds of arriving ships, port officials would pour boiling hot water from the upper levels down into the hold to see if screams from below would reach their ears. This is Iranian history – a history that must be faced, while also respecting the dignity and complexity of all the people who have gone through it.

4 comments

Thank you for writing this intellectually balanced and emotionally intelligent report. Any reasonable person with a capacity to reflect on aspects of oppression in our history will see how problematic this performance has been. I am truly baffled how we can argue that we are, as Iranian-Americans, so well integrated into American society, when we remain one of the least educated and inattentive minorities when it comes to issues of race. What makes us so unreceptive to the ongoing suffering of Blacks, Hispanics and Asian-Americans in this country?

Hi Aria, thanks for your comment and question, I will definitely follow up on it. What are some of the things you perceive as affecting ‘Iranian-American community’ consciousness and discourses on these issues?

Thank you Maziar for your prompt reply. I hope I didn’t grossly generalize. I see a sense of pride in my family and community (having made something of themselves) but no capacity to reflect on the fact that many others have not been afforded the same opportunities in this country. The U.S. society at large is also conflicted when it comes to acknowledging institutional racism. What are your thoughts?

Sorry again for the delay in responding. This is an interesting conversation–for me, some general questions which arise are: how do Iranians in the diaspora view themselves in comparison with other racialized and/or racial/ethnic groups? What current discourses promote, entrench and challenge these views held among “the community”? Also, which people, media outlets and organizations get to speak for who and what counts as Iranian, and what that means in relation to others? Much has been written on this subject academically and non-academically (including on this site, and an unapologetic plug for my brother’s article here: http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/4313/beyond-mullahs-and-persian-party-people_the-invisi).

I don’t think that Iranians are especially “unreceptive” to the ongoing suffering of other groups per se. When considering problems with racial consciousness among Iranians in diaspora, however, I believe that there is a lot to be said for historical factors such as 20th century promotions of Aryan identity and disproportionate valuation of genetic/cultural proximity to White/European people, which remain powerful discourses in the community. And there are very real pressures for all minorities to resist racialization and avoid persecution (individually and as groups), which many communities, including Iranians in the diaspora, attempt through assimilation and de-emphasizing aspects of their identities and histories. This contributes to an atmosphere which doesn’t leave a robust space for discussing and interrogating one’s own ascriptive identities, much less how they function (and stand in relation with other groups in the empire that is the US).

One more point–and I think there should be more discussion and writing on this–is how class (the large proportion of middle and upper-middle class Iranians) shapes the conversations and racial consciousness of Iranians in diaspora. Class shapes cultural outlook, exposure and material interests in ways that we don’t often examine. In regards to the problems of the more marginalized segments of the working class–ethnic minorities specifically–I believe that class interests among much of the diaspora affect relationships towards these communities.