This piece was originally published on The Tuqay before it became part of Ajam Media Collective.

It was written by Nick Danforth, a PhD candidate in history at Georgetown University in the United States. He is partly responsible for the Afternoon Map blog, a fantastic collection of historical maps and their context. A printable (.pdf) version of this story can be found here.

Anyone who has traveled in rural Turkey as a foreigner has undoubtedly had the experience of being taken for a spy. Most likely, anyone who has ever expressed interest in Greek or Armenian ruins has also had the experience of being asked, first jokingly but then seriously, with the offer of a 50/50 split. Indeed, combing the countryside for buried treasure has long been a popular pursuit in Turkey, as documented in the brilliant Yilmaz Guney’s inexplicably unwatchable film Umut (Hope). Sometimes finding the treasure involves religious incantations, but often, especially in Eastern regions, it involves trying to piece together the meaning in religious symbols or Armenian letters carved into stones around graveyards or ruined churches.

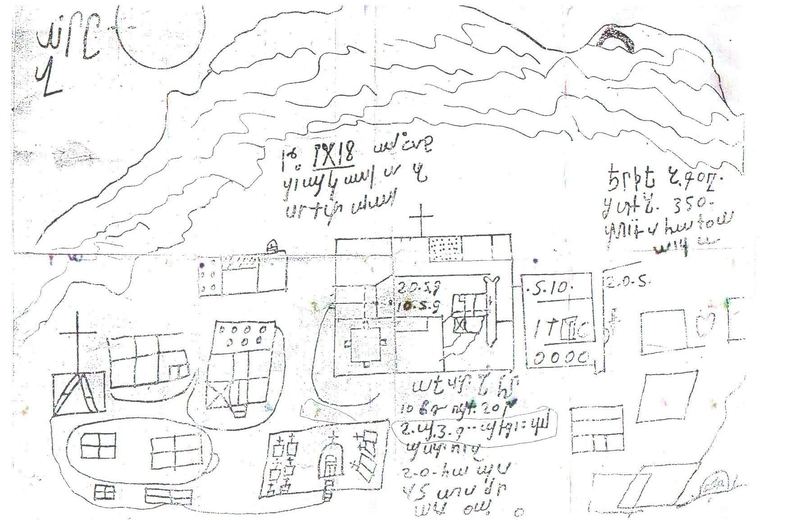

Countless websites, such as defineci.org or hazineavcisi.com, offer forums where users can discuss the meaning of these clues or ask for advice in interpreting local topography, as well as share found, photocopied, hand-drawn or annotated maps like these. Each letter or motif – a snake, a pair of birds, a cross, a cup, or anything else – can tell prospective treasure hunters which way to go, how many steps to take and how far down to go when they start their digging.

Much as (considerably more profitable) illegal excavations in or around official archeological sites wreak havoc with the digs, nighttime digging has sadly contributed to the destruction of what remains of many old Armenian buildings. As the tale of out-of-jail-but-still-under-indictment Cubbeli Ahmet Hoca makes clear, treasure hunting is perfectly permissible if carried out on your own property, but wrong when carried out on the property of others. Yet a mix of greed and poverty leads far too many people to ignore this advice. In the words of a carpenter living near the remains of St. Thomas Monastery by Lake Van, “villagers realize the real treasure is in preserving these ruins for tourism, but that takes time, and they are poor.”

Court cases going back to at least the 1950s suggest that frequently, rather than being a source of wealth for those who need it, treasure-hunting has been good business for swindlers who bilk the desperate poor while insisting that just a little more time and money will be enough to finally uncover a cache or riches. According to newspapers, mid-century cases most often involved digging in the basements of former Greek houses in and around Istanbul. More recently, though, the focus has been on Armenian gold, supposedly buried in poor, rural and formerly-Armenian populated parts of the Southeast.

Films like Umut present villagers’ faith in possibility of finding buried treasure as evidence of an enduring spirit of national optimism. In the context of Armenian gold, however, it is also a fascinating look into the politics of historical memory. Despite the state’s efforts to downplay the presence of Armenians in Eastern Anatolia’s history, people know they were there, and know that they left in a hurry. Yet locals’ fascination with the near-magical import of Armenian writing suggests at the same time they have been deprived of any real historical knowledge about these people. Yet it also suggests a popular suspicion, fostered by what history has been taught been taught, that Armenians may have had too much money to begin with that they stashed away in anticipation of returning to claim it and the land it’s buried under.

What makes the matter even more complex is that in many of these areas the locals are ethnically Kurdish. When it comes to the politics of memory, the relationship between Kurds and Armenians is particularly fraught. Aanyone interested in a bit of digital archeology can scroll through the history section of Wikipedia’s Kurdish-Armenian Relations entry to see just what details merited comments like “fixed baseless claims” and “reworded to reflect reality.”

Though Armenian rhetoric seeks to secure global recognition of “Turkey’s” genocide, many Armenians are well aware that a great deal of the killing that took place in 1915 was committed by Kurds. Indeed, massacring Armenians could be considered one of the last great multicultural endeavors of the Ottoman Empire, with Turks, Kurds, Circassians and formerly Bulgarian Muslims working together in service of some sort of religiously-defined national identity. But of course soon after, sometimes almost immediately after the killing was over, Kurds themselves became the new victims of state violence.

As a result, a shared sense of victimhood and anti-Turkish hostility has served to unite many of the most militant Kurdish and Armenian groups. Most famously, ASALA, the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia trained with the PKK in the Bekka valley, despite the fact that the maximalist territorial aims of both groups overlap considerably. At one point, Abdullah Ocalan even issued an official apology on behalf of the Kurdish nation for their role in the genocide, while still insisting that the Turkish state had put them up to it. In some cases Kurds living in what were once Armenian villages have made a point of adopting old Armenian names as a conscious rejection of the Turkish names imposed by the state.

The carpenter I met on my way to St. Thomas told me that the previous summer a group of Armenian tourists had come to visit the monastery. He and his father had insisted on inviting them in for dinner. Since the Armenians didn’t speak Kurdish or Turkish, and he didn’t speak Armenian, they were limited to basic gestures of friendliness and hospitality. Having myself been involved with efforts at promoting Turkish-Armenian dialogue in the past, it was tempting to think these might be the best possible circumstances under which such dialogue could occur.

It is tempting to imagine that if instead of all these meaningless treasure maps there was a good, comprehensive tourist map for people who wanted to visit some of the more dramatic and out of the way Armenian ruins in southeastern Turkey, it might lead to more meaningful interactions between current and former residents of the region. Locals would come to see that there was in fact money to be made in preserving these monuments, while the descendants of former locals might appreciate that local attitudes were motivated as much by ignorance as malice.