The following is written by Karine Vann, a freelance journalist based in Brooklyn. She received her Master of Studies in Musicology from Jesus College, University of Oxford in 2014, where her dissertation examined the assimilation of jazz music in Soviet Armenia. She writes about Armenian cultural heritage for Smithsonian.com.

Article cover photo is by Greg Davies.

***

“First things first… Kond might look like a ghetto. It’s not,” says Sevada Petrossian as a preface to our walking tour of Yerevan’s oldest neighborhood. Petrossian is an architect at a Yerevan-based firm called urbanlab.am, an organization that has spent the last five years working hard to garner attention for Kond. The firm has devoted many weekends to giving walking tours of this district to curious travelers, in hopes of highlighting its significance. According to Petrossian and his colleagues, Kond is uniquely situated in Yerevan’s urban fabric–both geographically and socially.

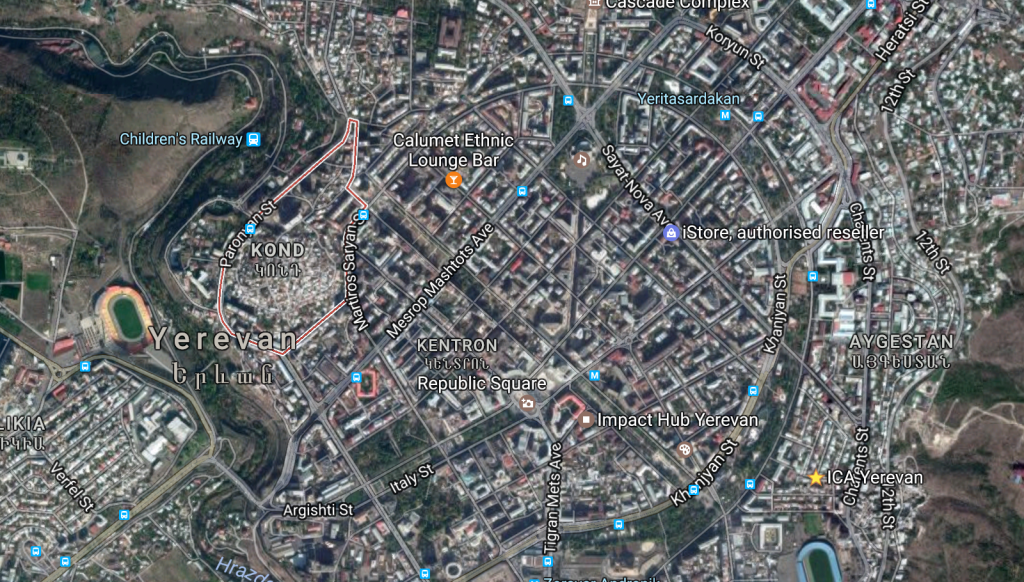

It isn’t clear how long Kond has been inhabited, says Petrossian, but the current layout has remained almost intact since the seventeenth century, back when Yerevan was a cosmopolitan crossroads at the intersection of different religions and ethnicities. The district’s name in Turkish was Tapabashi, meaning “hill top” and the word ‘Kond’ literally translates to “long” or “round” hill in Armenian. Its location on a hill has created a geographical barrier between the district and the rest of the city for centuries. On a map, Kond’s outline resembles a teardrop. caressing the western exterior of the circular main downtown area.

The deterioration from decades of neglect has taken its toll on the surrounding environment. Streets are crumbling, buildings appear to be sinking from their own weight, and residents’ living conditions are deplorable. It isn’t clear how long Kond has been inhabited, says Petrossian, but the current urban fabric has remained almost intact since the seventeenth century.

Despite the rough exterior, this structural neglect has actually played an important role in preserving the centuries of history in Kond. It is the reason most old buildings have miraculously avoided demolition. In stark contrast to the rest of Yerevan, Kond has not undergone any fundamental or radical architectural modifications in over three hundred years. Today, Kond hosts the most diverse array of architecture in the city.

Within the confines of its tear-shaped borders, one can find a smorgasbord of styles–anything from eighteenth-century brick houses and former mosques turned into makeshift housing, to luxury Soviet-era hotels and half-finished contemporary apartment complexes.

The area did not develop with the rest of Yerevan for a number of reasons. In the early twentieth century, when the rest of city was being remapped according to Soviet architect Alexander Tamanyan’s master plan, Kond was left relatively untouched. Tamanyan had intended to turn it into a museum district, but because Kond was home to so many residents, before implementing any structural changes, officials would first need to have a plan of relocating the several thousand newly Soviet Armenian citizens. It was an enormous logistical burden, which was never reconciled across the entire Soviet period. State officials always planned to do something, but never did.

Following the country’s independence in 1991, Armenia’s new government recognized the need to do something about the district. In line with the trends of modernist urban planning that dominated the nineteenth and twentieth century, where older structures all over the world were demolished to pave way for the new and “modern,” those plans involved decimating the whole area.

Fortunately for Kond, finances were insufficient to implement such extraordinary plans, but Petrossian says that each year, one by one, he sees old buildings replaced with new ones adhering to a more ‘modern’ style strangely juxtaposed against the rest of Kond’s deteriorating, yet historic charm.

The last century has seen Kond exist in a state of perpetual inertia. But its frozen state is a double-edged sword, one which has had profound consequences in the lives of its residents. Compared to the rest of the city, the standard of living in Kond is remarkably low and anyone walking through, without knowing its history, might easily mistake it for a slum. Petrossian tells us that many families don’t have access to running water–a standard commodity for other Yerevantsis (locals) living just down the hill. Many bathrooms take the form of outdoor shacks. Much of this one would expect to find in the villages surrounding Armenia’s capital, but certainly not its kentron.

Those seeking to preserve the identity of Kond face a number of obstacles, for the issue of heritage preservation is much more complex here than in, say, the ancient ruins of an Urartian temple where humans have not lived in for millennia. “When you talk about preservation, you usually talk about freezing something the way that it is now,” Petrossian says, “But here, there’s an ethical issue. Look at how the residents of Kond are living today. It’s a living city. You’re dealing with people’s lives.”

Despite their harsh living conditions, the people of Kond are remarkably resourceful. Walking through the city gives glimpses into the patchwork of construction materials residents use to circumnavigate material shortcomings. “It’s the best example of vernacular architecture,” says Petrossian, referring to the way residents transform their surroundings to suit their needs, oftentimes repurposing everyday instruments as building materials. He even recalls one residence constructed a new balcony made out of an old van.

“Public and private spaces of conventional cities don’t apply in Kond,” Petrossian warns us. Getting around the neighborhood requires walking into someone’s backyard, bearing witness to their undergarments hanging to dry within arm’s length, and sometimes even becoming active participants in the lively commotion on the streets. These unclear boundaries between public and private are what give of Kondetsis a reputation for being particularly friendly. As we walked by one residence, admiring its brick facade, a man yelled from up the street, “That’s my house, you can go ahead and go inside if you want! Help yourself!”

Today, little pathways connect the rest of kentron to the veiny streets of Kond and despite the main roads that exist, many locals prefer the hidden foot trails utilized for centuries. The city has changed, Petrossian tells us, but what’s amazing is that people’s instincts have remained the same. While this may be inconvenient for tourists seeking clear directions, it’s a fascinating window into subtle resistances to shifting ideologies expressed through urban planning.

Given that the incredible character of Kond’s residents are a result of both the centuries of regional cultural heritage, as well as the current hardships they face, what is that “authentic element” we’re looking to maintain when we talk about heritage preservation? What do you do when the same reason old buildings have not been demolished is the same reason people are living in poverty?

1 comment