The following is an interview with Ilkin Huseynov, a Baku-based artist, photographer, and publisher. In this interview, Ajam Editor Rustin Zarkar speaks with Huseynov about his recent book, “We Apologize for the Temporary Inconvenience” (2017) by Rally in the Streets Publishing.

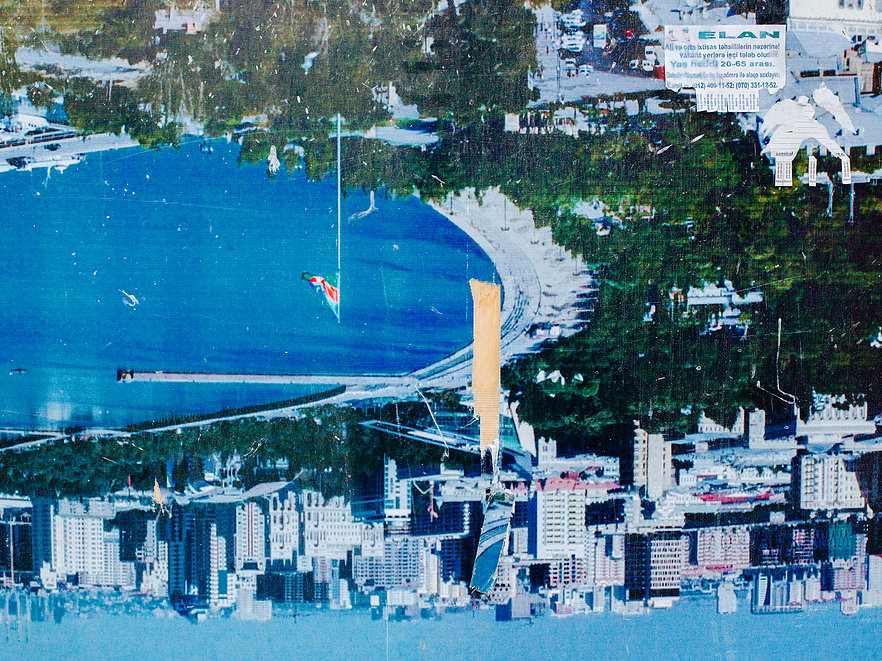

The book documents a municipality-led initiative to place graphic banners over active (and idle) construction sites in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. For more information on urban transformation in Baku, check out Mehelle, an AjamMC project capturing the sights, sounds, and memories of rapidly changing neighborhoods in the Caucasus.

1) AjamMC: Your book takes a detailed look at urban transformation and idealized visions of public space through the lens of banners covering Baku’s construction sites. Could you give us some background on the political and economic processes that fuel this development?

The title of the book is called “We Apologize for the Temporary Inconvenience,” but in reality this inconvenience is permanent. Since the second oil boom of the 1990s, there has been a constant string of new construction projects, often without any forethought. It is common practice for companies to break ground on a project before they have acquired the necessary funds to complete the building.

Due to limited financial resources, they rely on selling individual units to fund the later stages, and if they do not reach their goal, they will just freeze construction. This dilemma was exacerbated during 2015-16 manat crisis, so a good number of building sites remain idle. There are many people involved who do not have much experience in the industry, and they see it as a way to make a quick buck without considering the risks involved.

In order to mask the unsightly building process, Baku City Hall has placed banners on the fences and barriers that run along the construction sites. With this book, I want give a sense of the imposed artificiality that is slowly displacing the actual cityscape.

2) AjamMC: What did you notice as you were documenting these walls and barriers? What stood out to you about them? Can you speak about some tropes or themes that were used by the municipality?

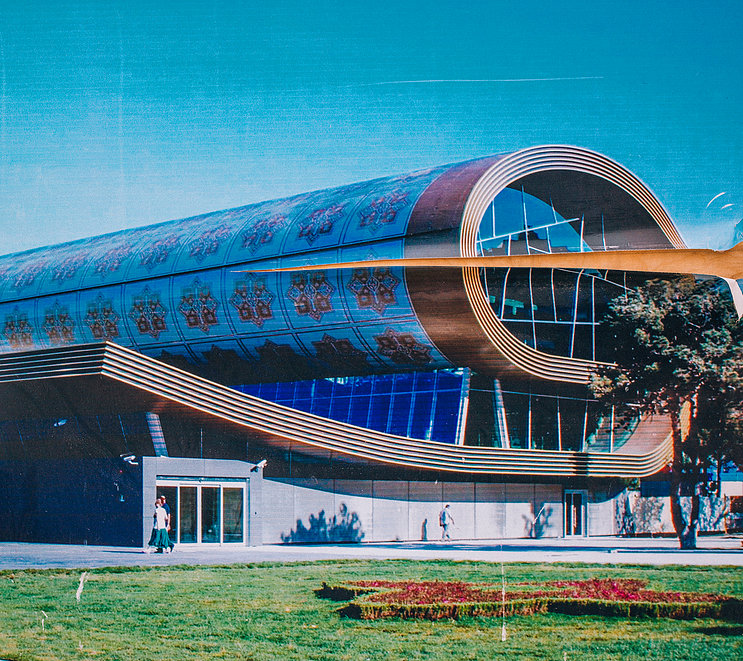

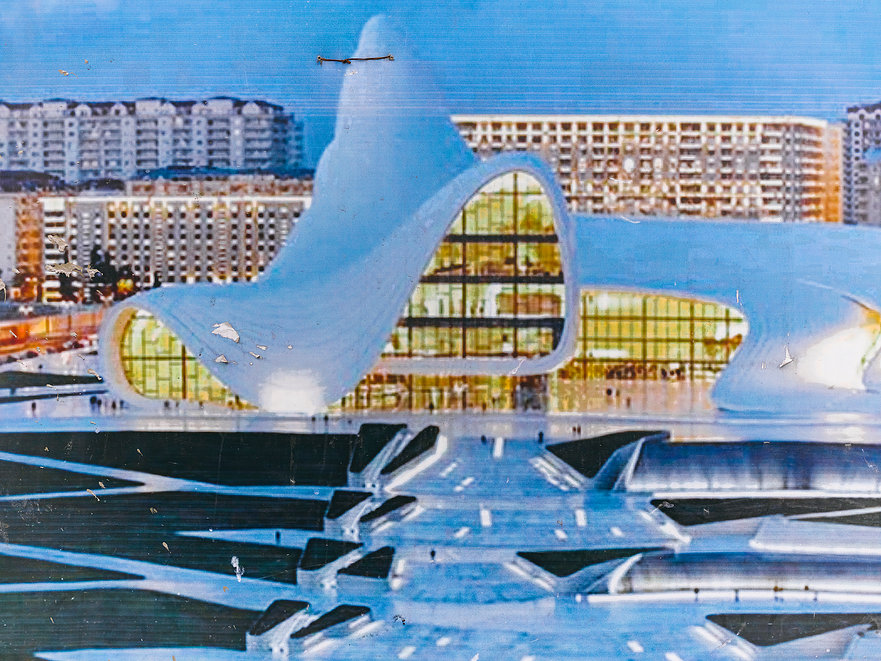

IH: There’s nothing unique about using billboards or banners to cover construction sites. In most cities the images depict the final plans of the projects being built in that particular location. In our case, however, the banners are rarely related to the spatial context, and instead consist of a wide variety of images that present ideas of the “utopian” city, notions of “beauty,” as well as Baku’s pre-modern and modern history. The people in charge want residents and tourists alike to see a particular vision of the city, without all of this construction.

Aesthetically, the photos themselves are not that impressive. They are pixelated, repetitive, and sometimes even placed upside down. Originally, I was more drawn to how they are affected by the environment and vandalism– how they have endured the aggressive elements here.

3) AjamMC: Who is responsible for the images that go up? Can you explain the decision-making process? How long has this been going on?

IM: It is a relatively new phenomenon, no older than a decade or so. It coincided with the construction boom of the mid 2000s, as well as the innovations in printing technologies. In Azerbaijan, it only costs ten or fifteen manat ($6-$10) to print five square meters.

As for the process, it is clear that there is not much thought or logic in the selection of images. I envision a group of district-level officials are told by higher-ups to choose from a certain number of categories. However, they are not provided with anything specific, which has resulted in them resorting to Google searches. In some cases, you can even see the watermark or copyright of the original photographer.

I’ve only seen one photograph that was taken by a relatively well known photographer; he had gone around shooting all the fountains of the city and was featured in an exhibition. The rest of them have been chosen randomly, coming from the tastes of personnel who use their imaginations to adhere to a vague set of criteria and directions. As you can imagine, this results in a very chaotic beautification initiative.

4) AjamMC: Regarding vandalism and environmental stresses, it’s clear that a lot of the banners are in bad shape. My favorite examples are of those photographs composed of different layers of banners.

IH: Interestingly, construction often remains static but the banners are updated frequently. For example, before every event like Formula 1 (annually), Eurovision (1202), or the European Games (2015), they will put up new banners right over the older ones.

The layering of the images sometimes reflects the process of capital accumulation fueling the construction boom— you can see photos from the oil industries, like rigging platforms and pipelines, with the iconic Flame Towers and other contemporary landmarks plastered over them.

I wanted to capture how the banners were able to inadvertently create a natural collage without any real artistic involvement through this layering process, so I designed the pages of the book to have different lengths and dimensions.

5) AjamMC: Yes, we see that oil features prominently on the barriers, even though It seems like an odd choice for beautification. Why do the banners stress oil imagery? Is it an homage to the economic and political history of the city?

IH: Oil is the national pride of Azerbaijan, and it has been stressed as part of the state narrative for more than a century. Of course, Baku wouldn’t be the city and major port it is today without the infrastructure, transport lines, and migration brought about by petroleum.

Oil is part of the city’s economic transformation, so I understand why it features so prominently in the images. I hear such sentiments quite often when I take photographs. People say, “Why are you shooting negative things? Don’t you see how things have changed? Look far we’ve come.”

6) AjamMC: Why did you choose this topic? What interests you about urban change in Baku?

IH: To be honest, I never thought I would ever be interested in urban change, architecture, or this kind of photography. My previous work mostly focused on social issues and people-centered stories, so I never imagined I would start a project that didn’t prominently feature people. My first book, Mühit, was very much about things that are hidden in plain sight. Whenever I would attempt to photograph objects, people, or places that were intentionally hidden for socio-political reasons, people would always ask me, “Why are you interested in that? Go and shoot something beautiful.”

After I returned from a trip to Spain, I was inspired by a new movement called post-photography, which documents found images that have been distorted and manipulated through photoshop and digital editing. As I scanned the city, I was struck by the artificiality of some temporary beautification material, as well as the various ideological narratives they were propagating.

I took people’s advice and shot what the authorities intended for me to see, but from a different perspective. Rather than going out and searching for what was hidden, I became interested in how things were hidden.

7) AjamMC: How did you undertake this project? How long have you been working on it?

IH: As you can imagine, there are hundreds if not thousands of construction sites across the city, and there’s not much information about where to find them. Often, I would just drive around, jot down the location of the banners, and return on foot.

Two months after launching the project, I participated in a group exhibition at Yarat! Contemporary Art Space. I had just started the project, and it would take me eight more months to fully realize it. I was still experimenting with how I would present this material, and I chose to highlight their wear and tear. I thought that these small details represented a disruption, and by shifting our attention, we can prevent the banners from rendering themselves neutral in our everyday life.

I keep returning to the idea of how things are hidden, so I want to continue the project by documented other forms of facades, especially the new cladding used to cover the walls of old housing blocks.

8) AjamMC: Regarding the composition of the book, your photographs only feature the barriers/walls, and we are left with no context or visual information about our surroundings. Is this intentional? Does it reflect something about the municipalities curatorial decisions for these barriers?

IH: I designed the book so the images do not reference their surrounding environment. In the first draft of the book, I included images where people, animals, cars, etc. were passing by. I wanted to show some semblance of the lived reality there, but I ultimately took out. Instead, I want readers to question what they are looking at and to ask whether it was an actual location or just an image of a place. There is this surrealistic feeling where you do not know where the photo ends and the environment begins.

As I have already mentioned, the banners provide little to no geographic context to the construction sites they are covering. This is pretty unusual. Take the example of Istanbul, the images seem to be carefully chosen and the projects are well-executed.

9) AjamMC: Sure, I see what you mean about Istanbul. The Galataport development project in the Karaköy neighborhood is an example of this. They are completely transforming the area and erasing traditional architecture, but at least the banners are propagating a narrative of historical continuity related to physical geography. So you are saying this context is not stressed in the case of Baku?

IH: Exactly, only in the Old City (İçərişəhər) do you see banners related specifically to the neighborhood. For example, in the book, there’s a few examples of banners covering the fortifications featuring the ancient walls and historical structures of the Citadel.

10) AjamMC: After publishing your book, do you think people have a different impression of these banners?

IH: After the exhibition, people would send me pictures of banners they had seen, and I recall speaking with an individual who told me, “you know, I never really see these banners, yet we pass by them everyday. They have become part of our environment.” The project encourages people to look past the banners’ utopian landscapes displacing the actual image of Baku. But you know, you cannot really conceal anything in this city. Sooner or later, the truth reveals itself.

2 comments