Belle Cheves is a PhD student in History and Middle Eastern Studies with a secondary field in the studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Harvard University. She primarily focuses on modern Iranian and Central Asian history.

On a crisp Cambridge morning, I climbed the steps of the Harvard Art Museums to meet Mira Xenia Schwerda, a PhD Candidate working on the history of photography and Middle Eastern art at Harvard University, who offered to guide me through the exhibition Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran. This show was masterminded by Mary McWilliams, the Norma Jean Calderwood Curator of Islamic and Later Indian Art at the Harvard Art Museums, and David J. Roxburgh, the Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Professor of Islamic Art History and Chair of the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Harvard University. Farshid Emami, now Assistant Professor at Oberlin, wrote an erudite analysis of the printed works to the exhibition, and Schwerda contributed the section on photography and the related essay in the catalogue.

“What’s really exceptional about this exhibit,” Schwerda told me as we prepared for the tour, “aside from it being one of the first on Qajar art since the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition on royal paintings in 1998, is not only its focus on non-royal Iranian art, but also its collaborative nature. It is the product of dedicated work from a curator, a professor, conservators, and graduate students.” In addition to the work of McWilliams, Roxburgh, Schwerda, and Emami, two conservators, Penley Knipe and Kathy Eremin, contributed to making this exhibit a feast for the eye and mind. Collaborative in many senses of the word, the exhibition brings together the four mediums of photography, painting, lacquer, and lithographic printing, elegantly illustrating the overlaps and evolutions of mediums and histories of Qajar Iran. The exhibit particularly emphasizes how technological innovations of the nineteenth century created new forms of artistic expression.

We begin in the section titled “Painting After Photography in Iran.” The images exhibited are paintings made after photographic or lithographic models. We pause at a painted portrait of Nasir al-Din Shah, which depicts the king in a room decorated with carved plaster and painted wood in typical Iranian fashion, yet he is surrounded by objects from around the world. A Chinese lacquer table poses to his right, a framed depiction of the Napoleonic war, which is likely a French chromolithograph, hangs on the wall behind him and an aneroid barometer, likely German or Swiss, is placed above it. The artist purposefully based the painting on a photographic source as Roxburgh explains in his illuminating catalogue essay:

In harnessing these new technologies, Qajar artists made doubly indexical objects: their paintings combined features simulating the photographic index – as the chemical impression of a sitter’s real presence – with the abstract modes of historical Persian painting – which favored pattern, bright color, and isometric space – united by the medium of paint applied by the hand. In translating the chemical residues of the photograph’s monochrome into the painting’s polychrome, subtle adaptations of the photographic source mutated its status from a reproducible image into a unique object fashioned by the painter’s hand.[1]

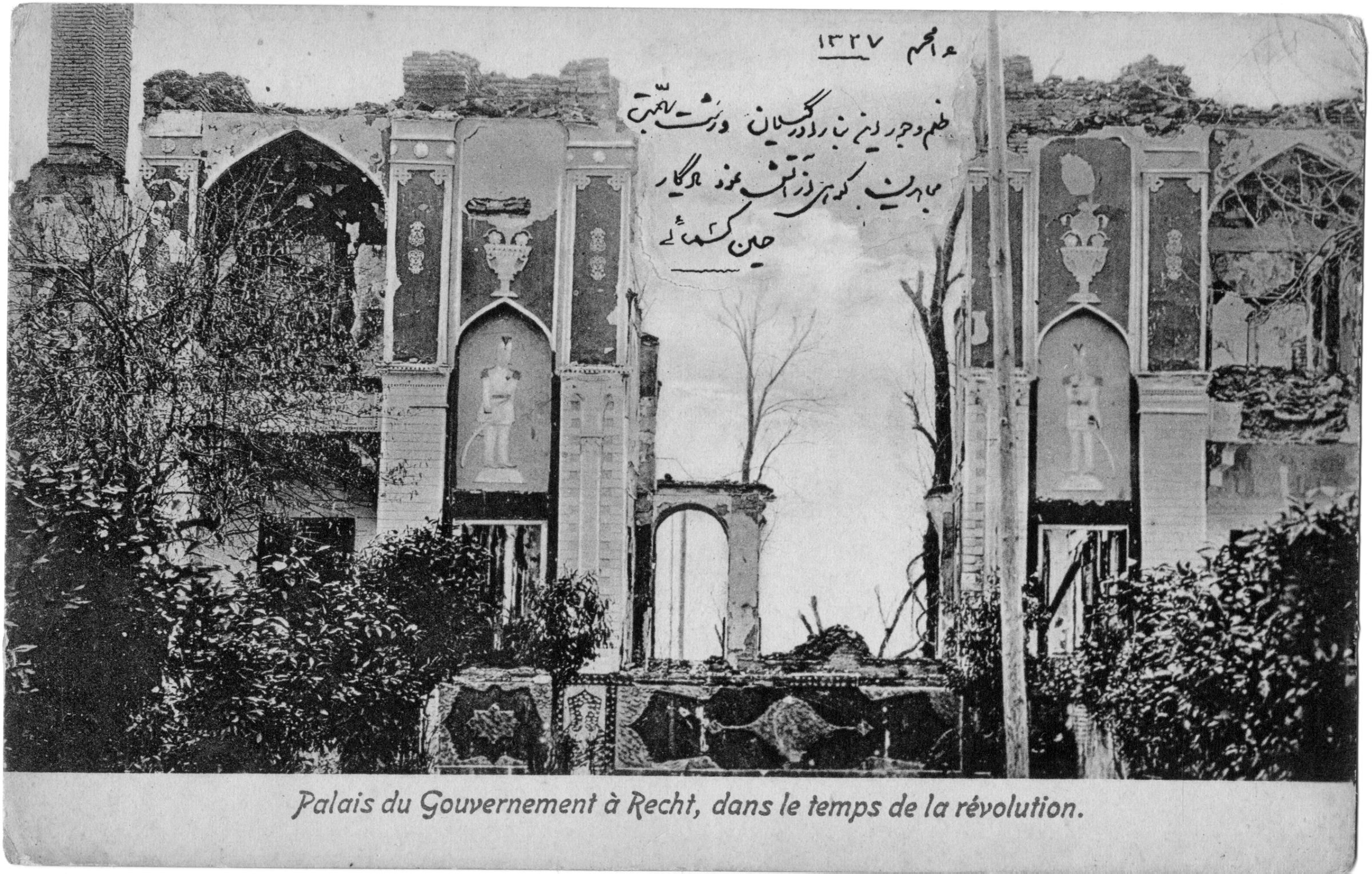

Mobility is the key theme of the exhibit, Schwerda notes – mobility of items coming into Iran from outside, mobility of images outside of the Qajar palaces, and mobility of the images themselves throughout various mediums. This becomes even more evident as we move to the section on photography. As Schwerda writes in her catalogue essay: “Iranian photography was never isolated from the global history of the medium and was continually shaped by the effects of polyglotism, travel, developments in technology and printing, and changes in audience and demand.”[2] Organized chronologically to demonstrate the development of photographic technology, Schwerda explains, “This section of the exhibit highlights how photography in Iran transformed from a luxury limited to the court into an agent of social and political change in just fifty years.” Images moved from the photograph taken in Tehran, to the painted photograph, to European travelogues, to American newspapers, to postcards traveling the world. And the artists were recognized around the world, as well. Antoin Sevruguin, for example, won awards at the world fairs of Paris and Brussels for his photographs of Iran.

We pause to examine postcards of the Constitutional Revolution. The postcards have captions in multiple languages, again highlighting the vast circulation of these images and their various national and international audiences. The photographic print in its portable form is not just a piece of art, but a political statement.

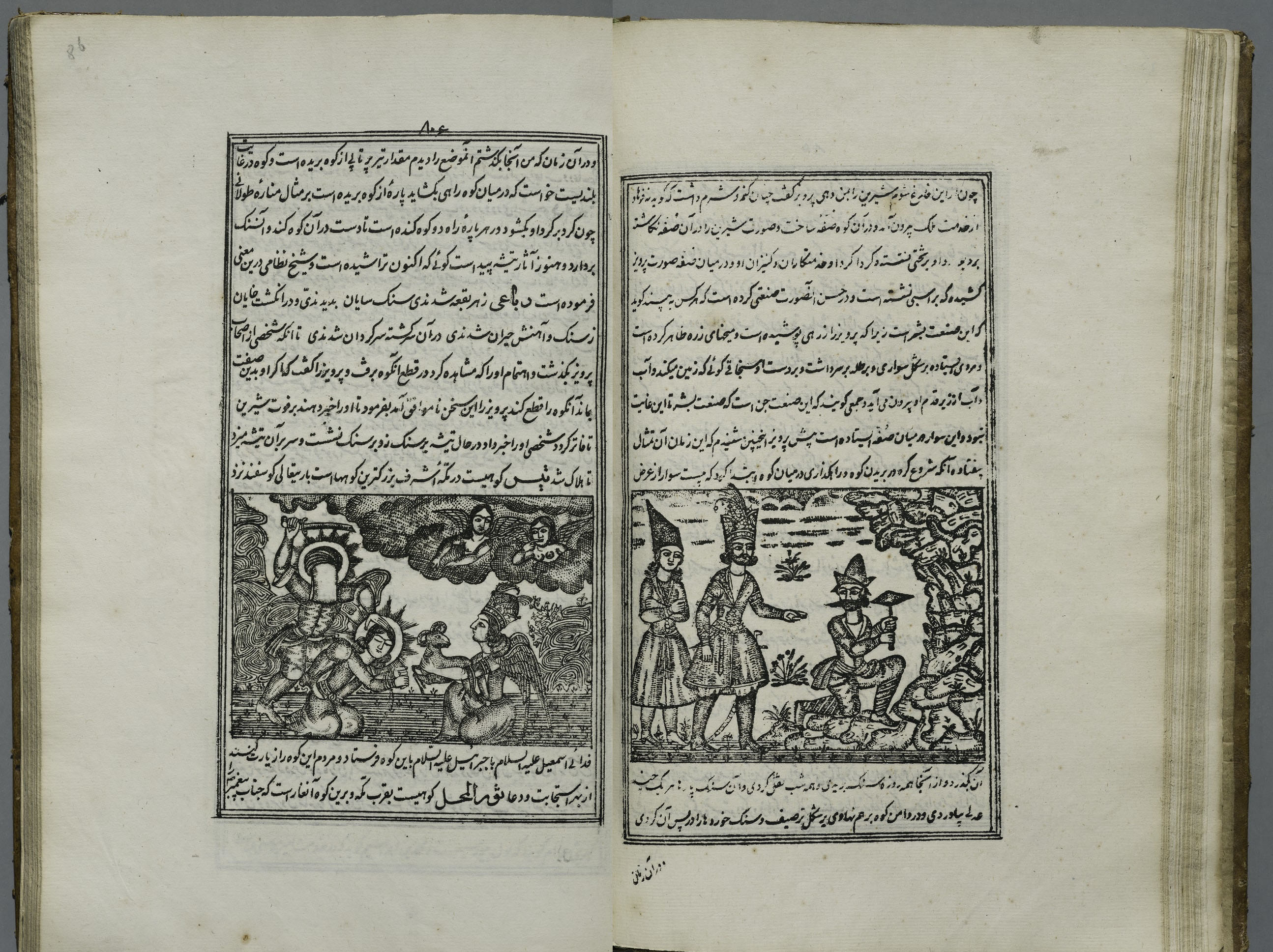

Next, we move to the section on lithography. The advent of printing in the form of lithography in Iran in the early 1800s, soon after its invention in Europe, was notable primarily because it allowed printers to continue the tradition of handwritten cursive manuscripts, but soon lithography also introduced novel formats, such as the newspaper or the poster. As Emami writes, lithography was soon embraced by Iranian artists: “Hailed as the image-making technique of the new age, lithography was appreciated as an art form in its own right, with artists specializing in the craft and signing their printed drawings.”[3] An early example of lithography in the exhibition is an 1847-48 edition of the encyclopedic compendium “The Wonders of Creation” written by Zakariya b. Muhammad al-Qazwini. The book’s drawings are partially the work of Mirza ‘Ali Quli, one of the first artists to specialize in printed images.

“Both manuscripts presented in this section were financed by merchants,” Schwerda tells me about the two lithographed Shahnamas displayed in the exhibition. New technologies brought in new patrons that permitted a greater level of circulation of images and texts to those other than the wealthy and royal – again the theme of mobility ever-present. “This whole exhibition is about new arts and also new audiences,” Schwerda says.

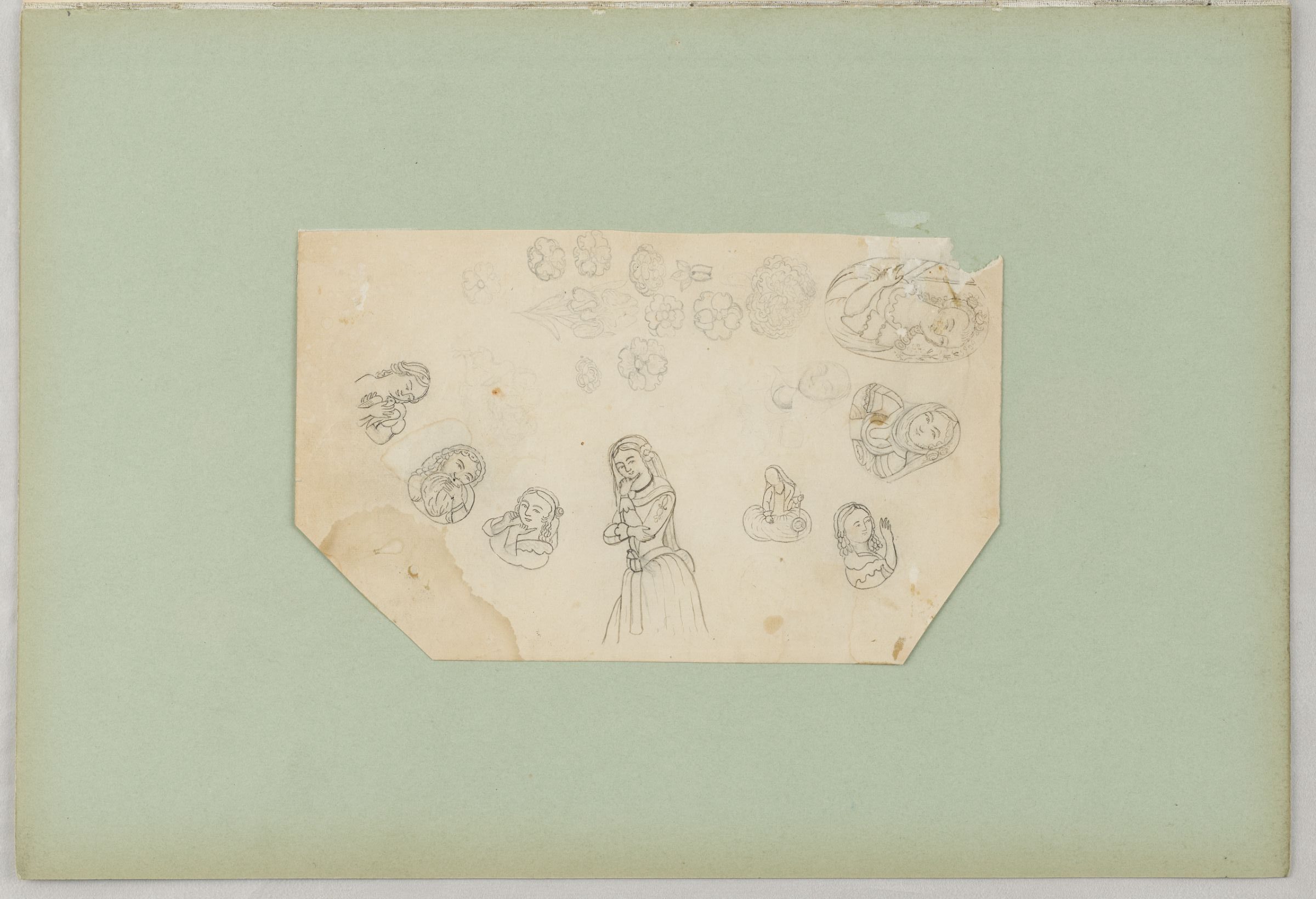

We then move to the section on lacquer work exhibiting the many forms and themes of lacquer work in 19th-century Iran as well as its production. The stunning examples of pen boxes and mirror cases feature more traditional but also novel themes, such as a mirror case with a birthing scene. The lacquer works are accompanied by preparatory drawings from a previously unpublished album most likely used in a workshop (see below An Album of Artists’ Drawings from Qajar Iran).

Another unique feature of this particular exhibit is its inclusion of Qajar women. While the paintings from the first section, similar to most books on the history of the Qajar era, focus on men, this lacquer collection, as well as the photography, highlight images of women and the domestic sphere, a topic of great interest in the 19th century worldwide. McWilliams describes the importance of the female imagery for lacquer work in her essay:

Female beauty is a nearly universal theme in the visual arts, and over the centuries Persian art has furnished innumerable examples of moon-faced, dark-eyed beauties with black tresses. It is, however, the European woman – clothed or unclothed, bust-length or full-figure – who populates Qajar lacquer wares to a startling degree.[4]

A remarkable example of featuring European women, in both the exhibition and McWilliams’ catalogue essay, is her discussion of the varied, yet connected depictions of a young pensive woman.

There are two drawings of the woman in the artists’ album and she also appears on both an Iranian pen box and a pen box produced in Russia for the Iranian market. McWilliams discovered the inspiration for the figure, a chromolithograph produced by the French artist Bernard-Romain Julien, published in both Paris and London. This group of art works again emphasizes not only the mobility and cosmopolitan character of Qajar art, but also that it can only be understood by analyzing different forms of mediums together.

We appropriately end on a photograph of a fruit stand in Tabriz that has multiple prints hanging on the walls and from the ceiling. Not only are the artists themselves interested in what’s happening outside Iran’s borders, so are the audiences consuming this art made available to them through the new “technologies of the image.”

Before leaving the museum, I stopped at the bookshop to glance at the three catalogues accompanying the exhibit and outlining aspects of the collections (see below).

The exhibit will be open until January 7th, so if you are in Cambridge or the Boston area, take the opportunity to stop by the Harvard Art Museums to see this extraordinary exhibit. I hope to see exhibitions on modern Middle Eastern and Central Asian art more regularly at the museum in the near future!

BOOKS:

Roxburgh, David J. and Mary McWilliams, eds. Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran. Cambridge: Harvard Art Museums, 2017.

This is the catalogue accompanying the exhibit, which includes essays by Roxburgh, McWilliams, Schwerda, and Emami.

Roxburgh, David J., ed. An Album of Artists’ Drawings from Qajar Iran. Cambridge: Harvard Art Museums, 2017.

This is a compilation of work from nine graduate students who worked on the album of drawings from the era, which is included in the book as a facsimile.

Farhad, Massumeh, Mary McWilliams, and Simon Rettig, eds. A Collector’s Passion: Ezzat Malek Soudavar and Persian Lacquer. Washington and Cambridge: Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, and Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, 2017.

This provides information not only on the lacquer work highlighted throughout the exhibit, but also includes information about additional lacquer objects, which were given to the Harvard Art Museums and the Freer|Sackler Galleries.

***

[1] David J. Roxburgh, “Painting After Photography in 19th-Century Iran,” in David J. Roxburgh and Mary McWilliams, eds. Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran (Cambridge: Harvard Art Museums, 2017), 125. [2] Mira Xenia Schwerda, “Iranian Photography: From the Court, to the Studio, to the Street,” in David J. Roxburgh and Mary McWilliams, eds. Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran (Cambridge: Harvard Art Museums, 2017), 81. [3] Farshid Emami, “The Lithographic Image and Its Audiences,” in David J. Roxburgh and Mary McWilliams, eds. Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran (Cambridge: Harvard Art Museums, 2017), 56. [4] Mary McWilliams, “Qajar Lacquer as a Medium of Exchange,” in David J. Roxburgh and Mary McWilliams, eds. Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran (Cambridge: Harvard Art Museums, 2017), 36.