A resident of Amsterdam, Saba Askary is a researcher and curator in the field of Art History and, with it, concepts of changing our past and future through new interpretations. She is currently managing the development of Unseen Media – an online photography platform and print magazine focusing on the new and emerging.

Pixelated

The following article is the first of a series titled, “Pixelated” by Saba Askary. While spaces dedicated to the medium pop-up and museums actively collect it, ‘digital art’ is still considered a non-art to most. Evolving from the multimedia and computer print art of the 70s, its barebone definition is any practice using recent technology in its creative process and the web in its circulation. Today, Creative Coding and Gif Art are only some of the many sub-genres in this silently engulfing movement.

But the break away from physicality, white walls, dealers and priceless auras lead many to suspicion. Where’s the indicator of value? When is it art and when is it content?

What we can be sure of is this. New technology invariably changes art. In the mid-19th century French ‘plein-air’ painters ventured outside their dark studios holding recently-invented, transportable tubed oil paints. In the fresh open air they decided to focus their paintbrushes on light instead of shadows – this small shift in perspective lead us to Impressionism and Modern Art in its wake. More recently, through web dissemination, fine-art photography has proliferated across the art world with its accessibility and relatability – a precursor to the digital. For better or worse, the more permeating medium ultimately wins over history, and what’s more enveloping than the rise of our digital consciousness?

For the moment, though, ‘digital art’ continues to live as non-art, where categorization is murky and experimentation is rife. When an artist is considered a ‘digital’ artist is not clear at all, including to themselves. This is the first in a series of posts looking into the practices of those who may be termed ‘digital artists’ stemming from the Ajam region, and who use it to look back home; critically, nostalgically or surrealistically.

Though few and far in between, these artists confirm the democratising effects of the art form. Not only through its potential for viral circulation, but in its uncanny ability to empathise with a wider group: to everyone experiencing the whirlwind of the 21st century.

***

Toronto-based, Afghan-born artist Shaheer Zazai considers himself a strict traditional painter, an important pillar of his identity and practice over the years. But in the first days of 2013 he found himself sitting in front of his laptop, feeling unproductive.

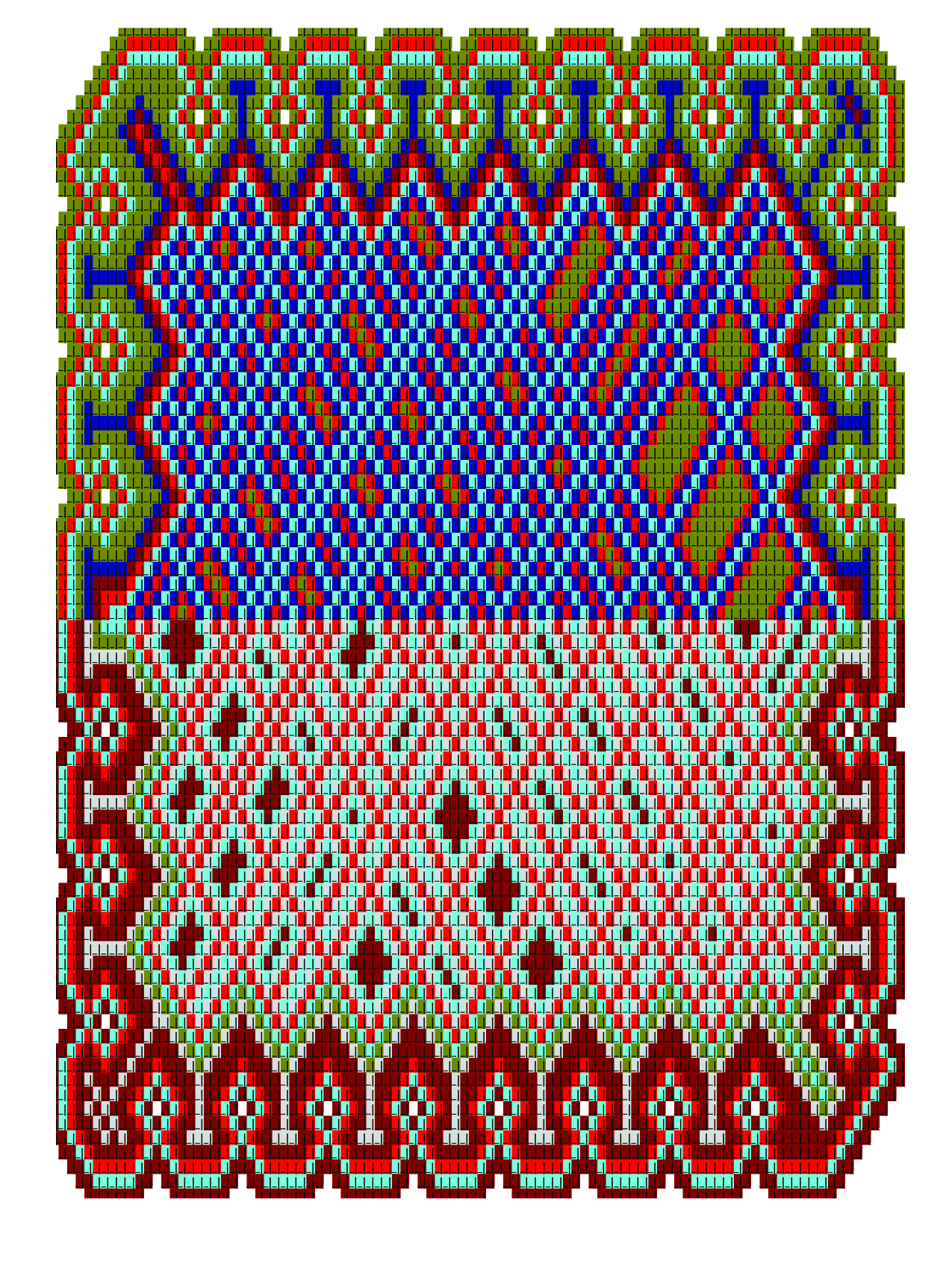

Contemplating the year ahead, Zazai gave himself the challenge of typing not words, but 2013 dots and spaces into a Microsoft Word document. The result was not all that effective, so he began to assign highlighter tones to the forming document, designating spaces and directions to them. These abstractions were at first intended to aid Zazai with his creative flow, as sketching naturally would. But the more he moved away from developing patterns, the more unintentional patterns emerged in each document. So much so that a few months later Shaheer stopped resisting and enrolled in a digital painting residency in order to produce a life-size Afghan-carpet, on Word.

This marked the beginning of the Carpet Series – a group of improvised designs painstakingly developed through stitched Microsoft Word pages. Each punctuation and character (translated to single knots on a carpet) are typed out one by one, never using the crutch of Copy and Paste and with a repertoire of only 15 highlighter tones. It takes Zazai 5 to 6 hours to complete a page, and up to 40 hours per carpet. Within the software’s limitations Zazai found his creative niche. And to his surprise, this niche began to attract considerable attention from the art community, more so than his paintings were ever able to muster.

“The more attraction the digital work received, the less I was interested in presenting it.”

resident from Shaheer Zazai on Vimeo.

But in the moment Zazai opted to turn the other way, tuning out the exponential interest his digital works were garnering. He considered his painting practice to stand above art made on a computer program, and many would agree. While the digital works were prettily appropriated Afghan carpets, his paintings spoke of war, power-struggles, revolutions and patriarchy, a common view of a reeling Afghanistan.

When he was six, Zazai’s family were displaced from their home in Kabul due to the rise of the Taliban and impending civil war. They fled to Islamabad, Pakistan where Zazai spent his remaining childhood, moving to Toronto and art school at the age of 19. Years later in his studio, as Zazai typed in an arduous carpet in Word, he had an epiphany. It was his displacement, detachment from culture and resulting identity crisis that had seeped into the paintings, rather than a critique of a country at war.

Nostalgia is embedded in progress – as changes speed up around us we often lose footing and are pulled towards a sense of ‘home’. If we cannot go home, roots must be planted fast or the tide may carry us away. With the meditative Carpet Series Zazai suddenly found his ‘home’. His family’s traditional Afghan carpets were some of the sole items that travelled with them as they moved from place to place, the wool under their feet linking them to their vivid Afghan heritage.

“…whilst working on the digital series, the works somehow changed my perspective towards everything in relation to my identity. I no longer felt the drive to criticise my background. Instead, I have come to realise that identity is dependent on the perspective we choose to associate with or act in rebellion of.”

In the years since Zazai first creatively engaged with a Microsoft Word document, he has only now resolved his biases against a digital practice. His first solo show of the work opened earlier this year at Double Happiness Project, Toronto – consisting of prints, video, and a handmade carpet woven in Afghanistan and based on Zazai’s first document.

His practice has come to expose the parallel between computer programs and the programmable nature of textiles. By the first Industrial revolution, programming through punch cards were used in the production of textiles through a jacquard loom. Carpet weavers were similarly using the language of knot density, counting the wefts and warps on the backside of a carpet per square inch to identify a carpet’s region, possible weaver and quality. Computers and textiles have shared histories, 0s and 1s mirror wefts and warps.

What’s more, Zazai’s Carpet Series bridges a gap between a cultural product made by ‘The Other’ and his adoptive Western culture. You may not know how a carpet is woven, but the ins and outs of Microsoft Word (and its frustrations) are second nature to those who grew up in the digital age, and the painstaking effort undergone with each piece is not lost, but celebrated by us. Here lies the potential strength of this silently engulfing movement. With an increasingly bubbled and polarised future to look ahead to due to these same technological advances – could the rise of digital artists extend the planks that bridge our differences? Potential awaits within each of our screens.