The following article is written by Christopher Stedman Parmenter, a Ph.D. Candidate in Classics at New York University. His research focuses on unfree mobility, cross-cultural trade, and ideas of ‘race’ in the Archaic Greek world (c. 700-479 BCE). He has published in scholarly journals including Bibliotheca Orientalis and Classical Antiquity (forthcoming). This article includes materials donated to the Ajam Digital Archive, an online repository that focuses on twentieth century Persianate Life. If you would like to contribute to the Archive, see here.

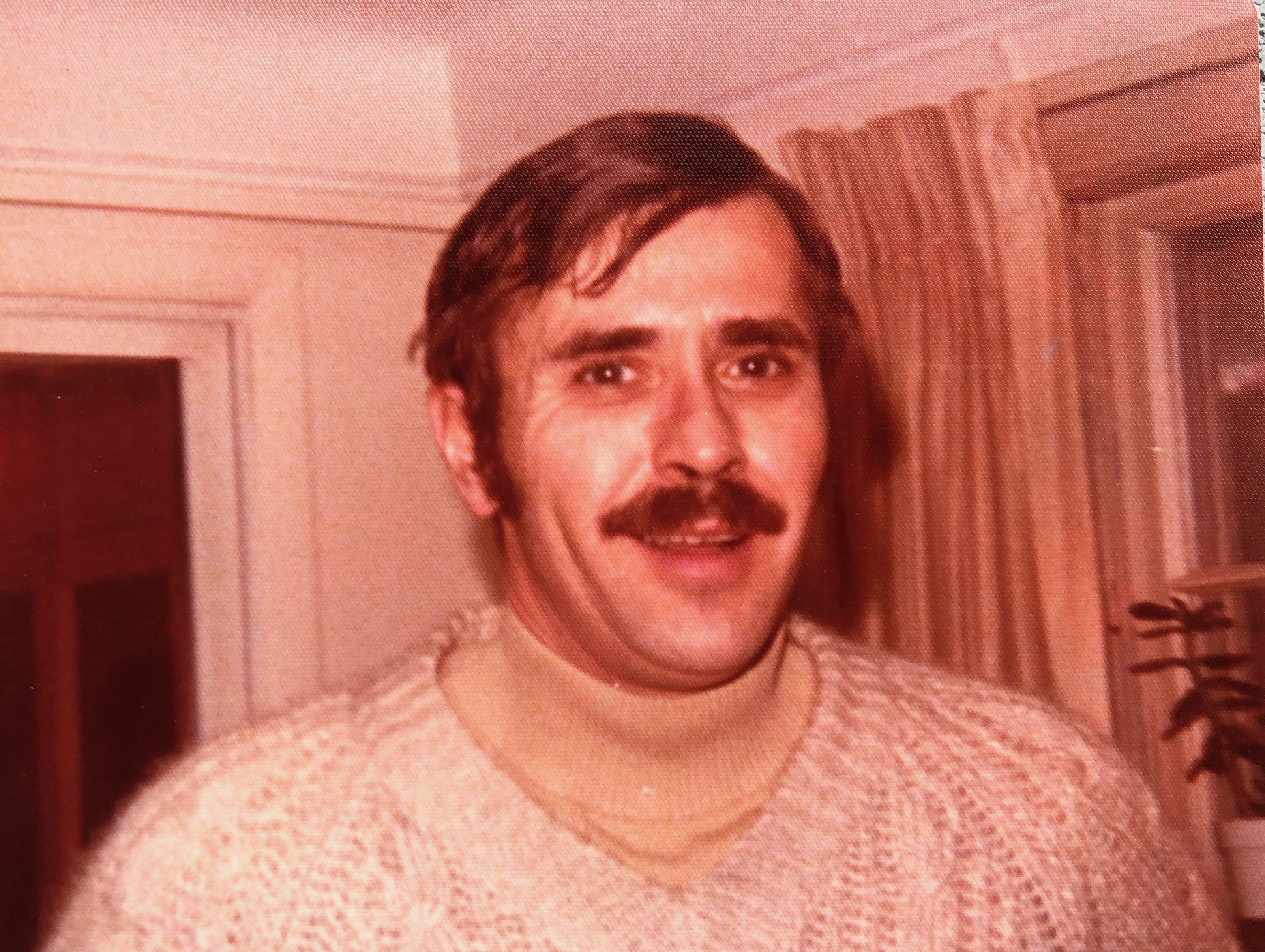

George Luther King, Jr. waited until the last decade of his life to rediscover his Armenian roots. Despite his dark hair and brown skin, my grandfather (1934-2001) unquestioningly identified as ‘white,’ like most Armenian-Americans of his generation. Orphaned at a young age and raised by his Anglo relatives, it was only after retirement that he began to reflect seriously on his mother’s family, the Michaelians. His Armenian reawakening was the backdrop of my childhood: when he chose an Armenian epitaph for my aunt’s gravestone; when he signed his emails ‘Kevork;’ when he chatted up the parents of Iranian and Arab students at my school; when my mother took up ‘Armenian’ cooking.

Why would my grandfather develop such enthusiasm for the homeland in his sixties? He didn’t speak the language. No Armenian had inhabited his ancestral village in eight decades; he had little in common with the new Armenian migrants that had arrived from Iran and the former Soviet Union since the 1980s. In embracing Armenia, George King was seeking to answer a silence about his origins that had been deliberately cultivated by his grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins after they had proved their right to remain in America. Scholars have noted the repressed trauma that weighed down many diasporic Armenians in the twentieth century; having survived the genocide, they needed to adapt to new countries with their access to the old cut off. But this was not quite my family’s case, at least for those who lived long enough to know my grandfather. Among the earliest Armenians to migrate to America, the Michaelians had been in New York for 30 years when the genocide started.

Rather, the Michaelians’ silence about their migration was a deliberate strategy of moving past unsettling memories of the U.S. government’s own attempt to expel the Armenian community between 1909-25 and, ultimately, assimilate into a comfortable place in America’s racial hierarchy. Using a collection of their papers that had been carefully preserved by my grandfather, I have reconstructed the Michaelian family’s narrative of migration and assimilation. George King’s reawakening as an Armenian was part of a broader shift in the calculus of race, power, and ancestry that was taking place in American culture during the 1990s. While throughout the early twentieth century, identifying as Armenian posed a threat to the family’s American citizenship, by the end of the century the Michaelians could embrace their Armenian heritage without the fear that it could contradict their whiteness.

Age: 30 years.

Stature: 5 feet, 7 inches, Eng.

Forehead: [illegible] (medium size)

Eyes: Dark

Nose: Medium

Mouth: Medium

Chin: Short

Hair: Black

Complexion: Dark

Face: Regular

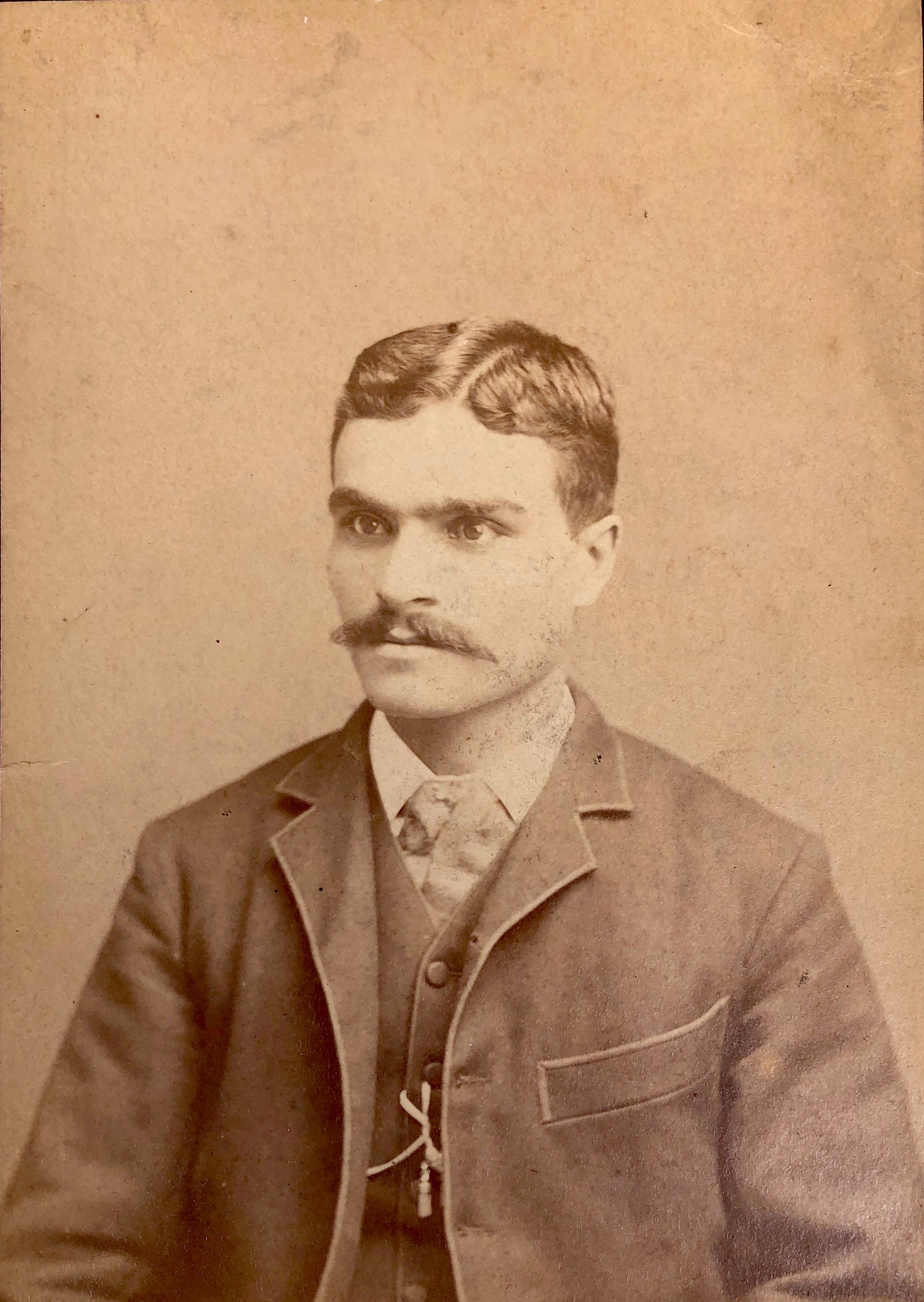

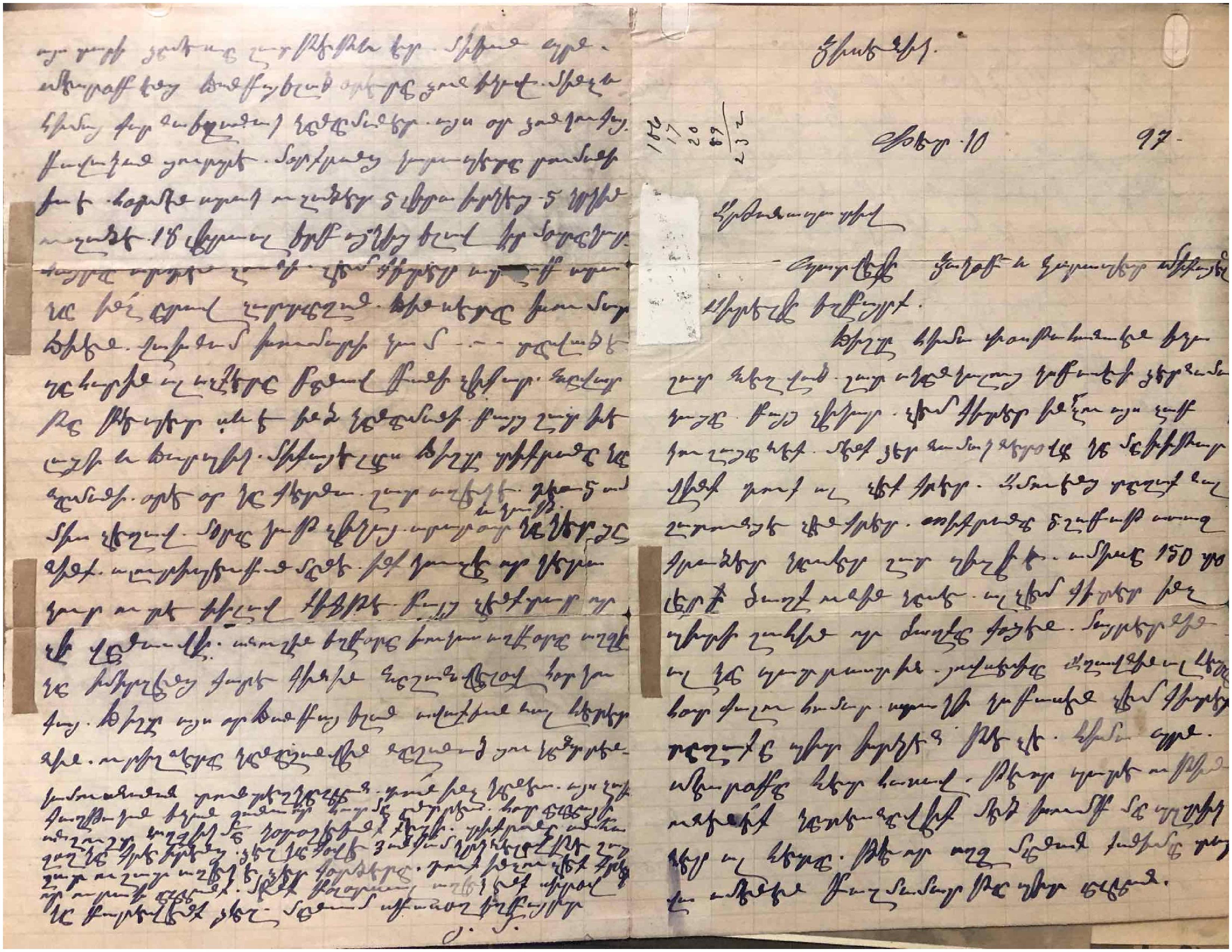

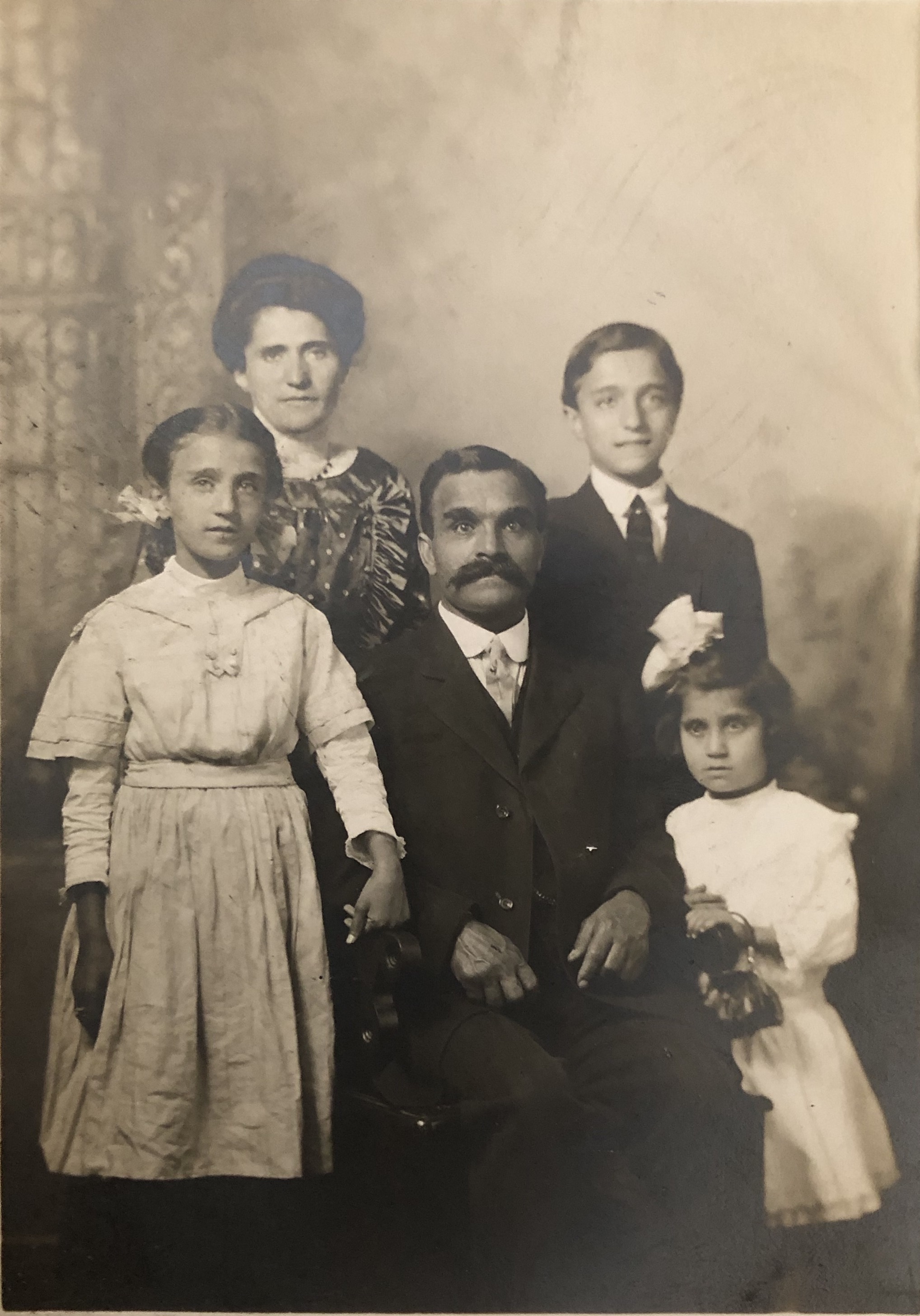

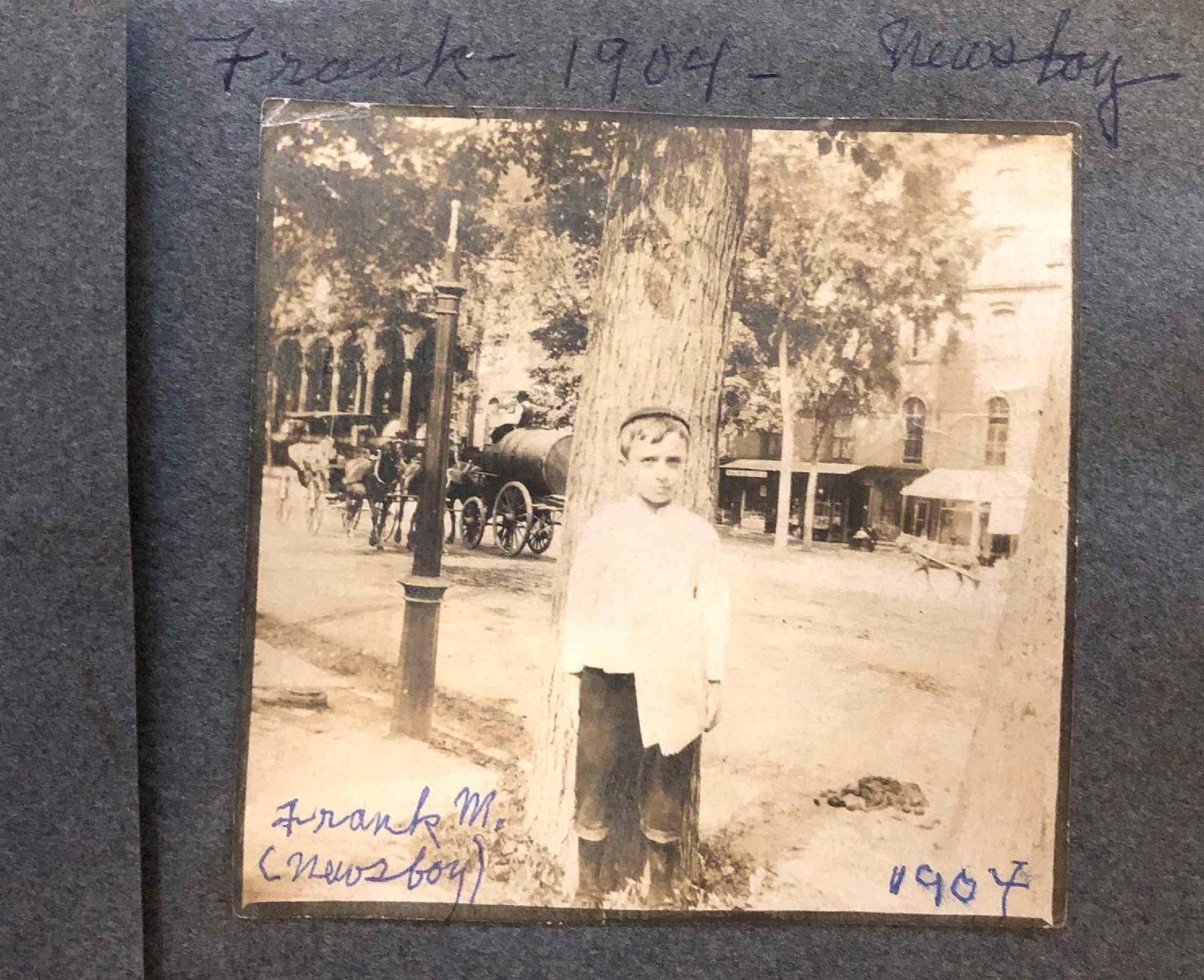

On October 21, 1891, my great-great grandfather Hohannes Mikhailyan (1861-1928)—known legally as John Michaelian—applied for a passport for a sixth-month trip abroad to find a wife. Born in “Harpout, Turkey in Asia,” as he writes on his application, he and his brothers had emigrated to the United States in 1884. It was an unfortunate moment to return home. Hohannes arrived at his ancestral village of Huysenig, just outside Harput, at the start of the pogroms instigated by Sultan Abdul Hamid II between 1894-96. He and his new family—his wife, Tevrez (1874-1954) and Armenian-born children Florence (1893-1979) and Frank (1896-1978)—would be denied permission to leave until 1897. Near the end of their harrowing ordeal, Hohannes writes to his brothers in the United States, noting that many locals had obtained passports to escape. If economic opportunities abroad had already been draining Harput of its best educated and most mobile students for years, the Hamidian massacres swelled the exodus into a flood.

The Michaelians were exceptional migrants. The brothers Hohannes (John), Garabed (Charlie) (1867-1939), and Boghos (Paul) (1879-1915) came to the American northeast having been educated by Protestant missionaries at Euphrates College in Harput. They were fluent in English and, like many graduates of Protestant schools, came equipped with letters of introduction. Their brother Hagop (Jacob) (1854-1931), who had been ordained as a minister at Anatolia College in Merzifon, preceded them by a year. Although Hohannes and Hagop made extended returns to the Ottoman Empire after their initial migration (the latter served as a Protestant minister in Constantinople between 1887-92), the four brothers had committed to staying in the U.S. In 1897 they pooled their money to found Michaelian Brothers & Company in New York, importing newly-in-vogue ‘Oriental’ rugs.

The Michaelians were exceptional migrants. The brothers Hohannes (John), Garabed (Charlie) (1867-1939), and Boghos (Paul) (1879-1915) came to the American northeast having been educated by Protestant missionaries at Euphrates College in Harput. They were fluent in English and, like many graduates of Protestant schools, came equipped with letters of introduction. Their brother Hagop (Jacob) (1854-1931), who had been ordained as a minister at Anatolia College in Merzifon, preceded them by a year. Although Hohannes and Hagop made extended returns to the Ottoman Empire after their initial migration (the latter served as a Protestant minister in Constantinople between 1887-92), the four brothers had committed to staying in the U.S. In 1897 they pooled their money to found Michaelian Brothers & Company in New York, importing newly-in-vogue ‘Oriental’ rugs.

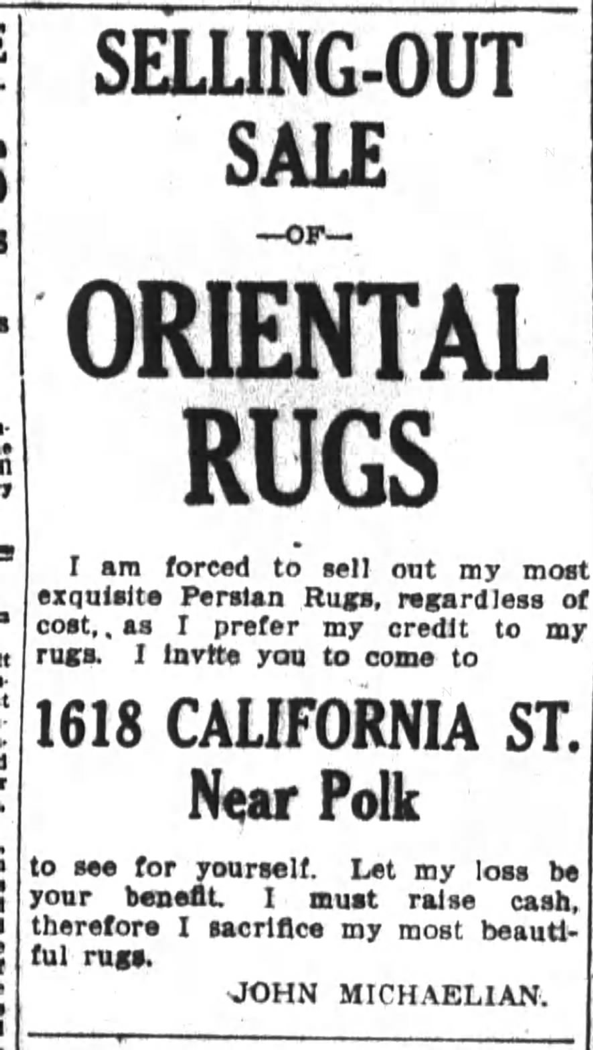

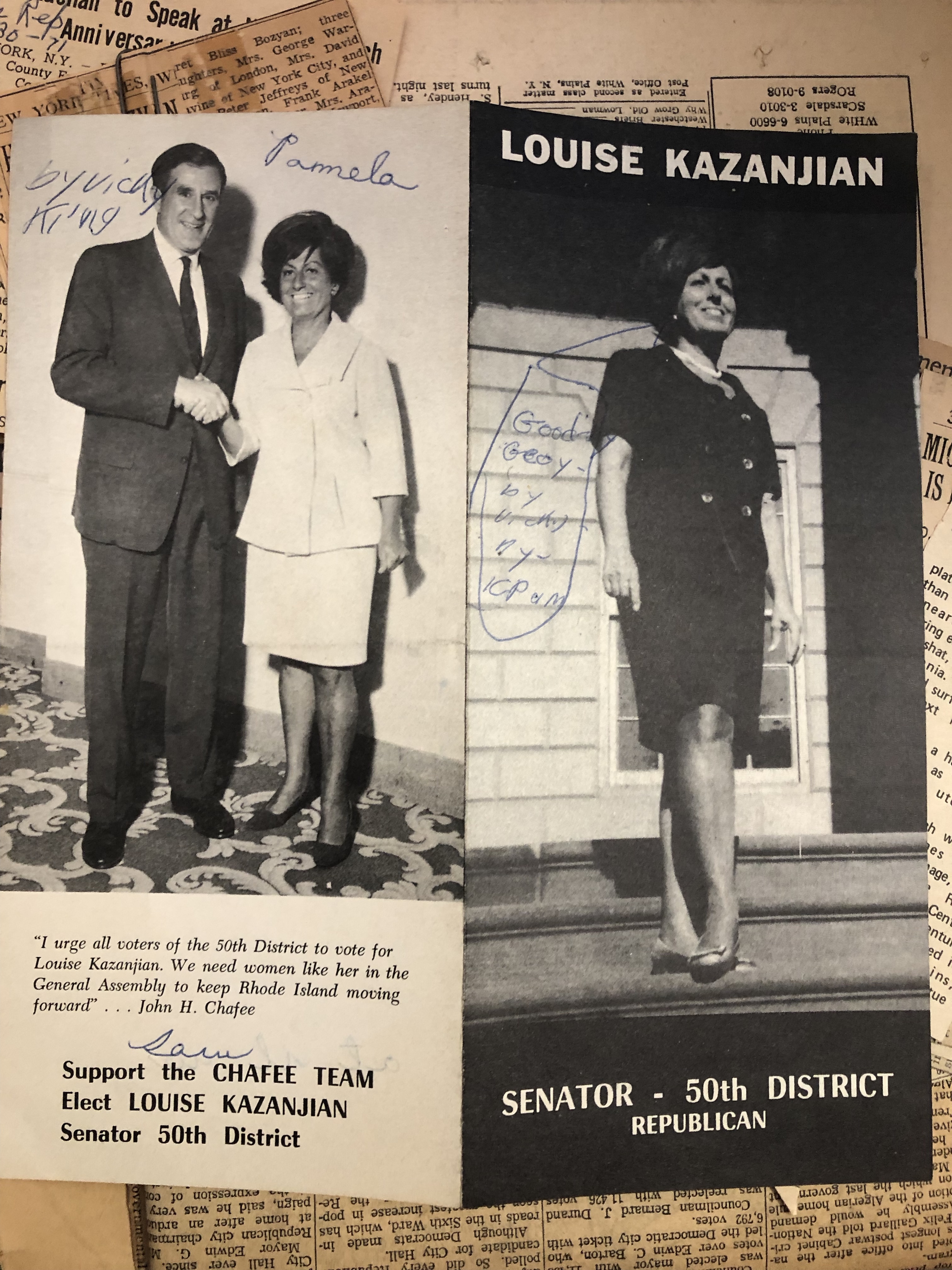

Migrants from the Harput region were prominent in the early American rug business; the first Armenian firm was founded by another son of Huysenig, Hagop Bogigian, in Boston in 1876. The Michaelians were clever in repurposing Orientalist caricatures into a marketing strategy. “I am forced to sell out my exquisite Persian rugs, regardless of cost, as I prefer my credit to my rugs . . . let my loss be your benefit!” writes Hohannes in a 1908 advertisement, channeling one pervasive stereotype. The brothers leveraged ties with other Huysenig families, including the Aronians of New York, Kazanjians of Providence, and Bozyans of Newport, for access to inventory and capital.

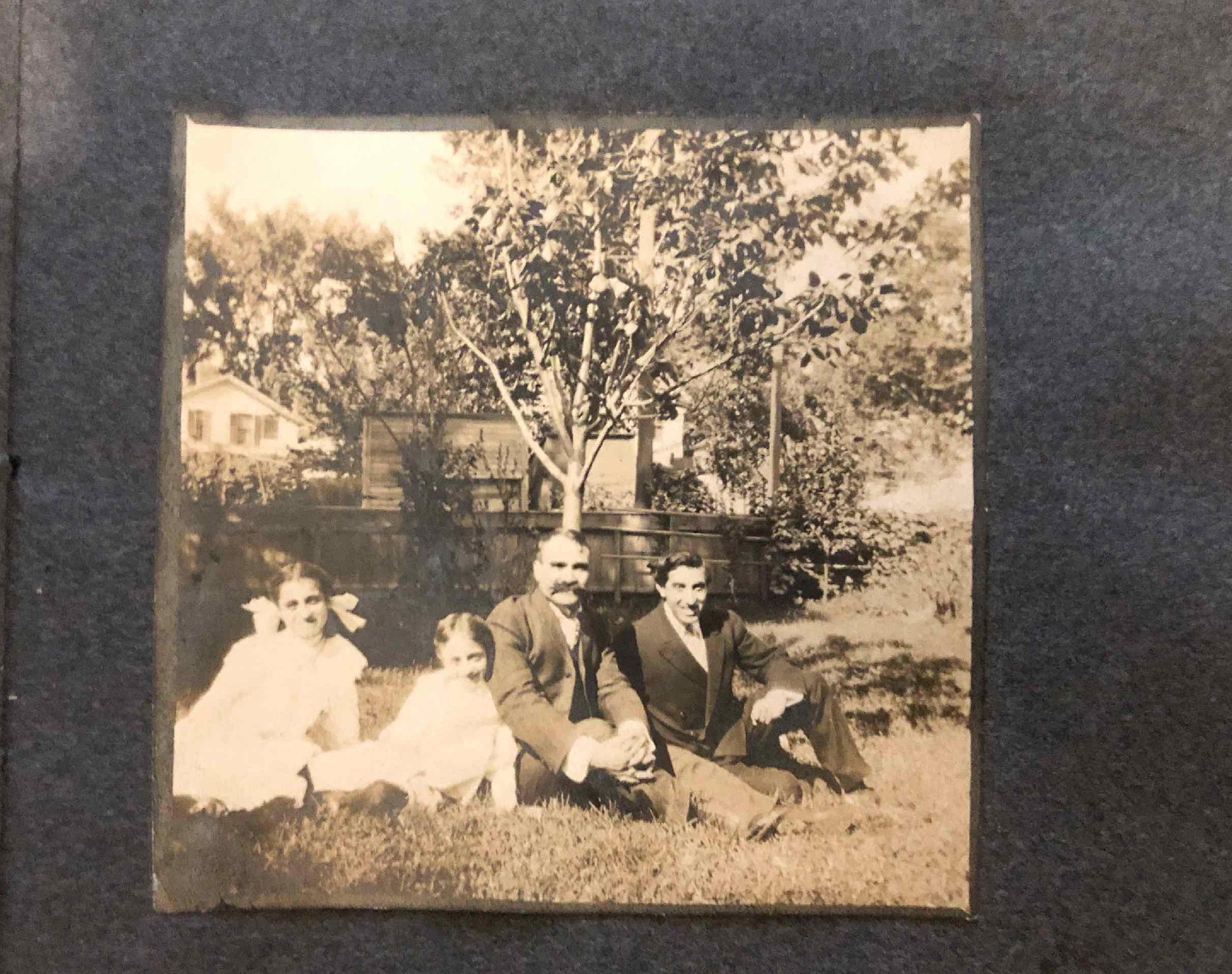

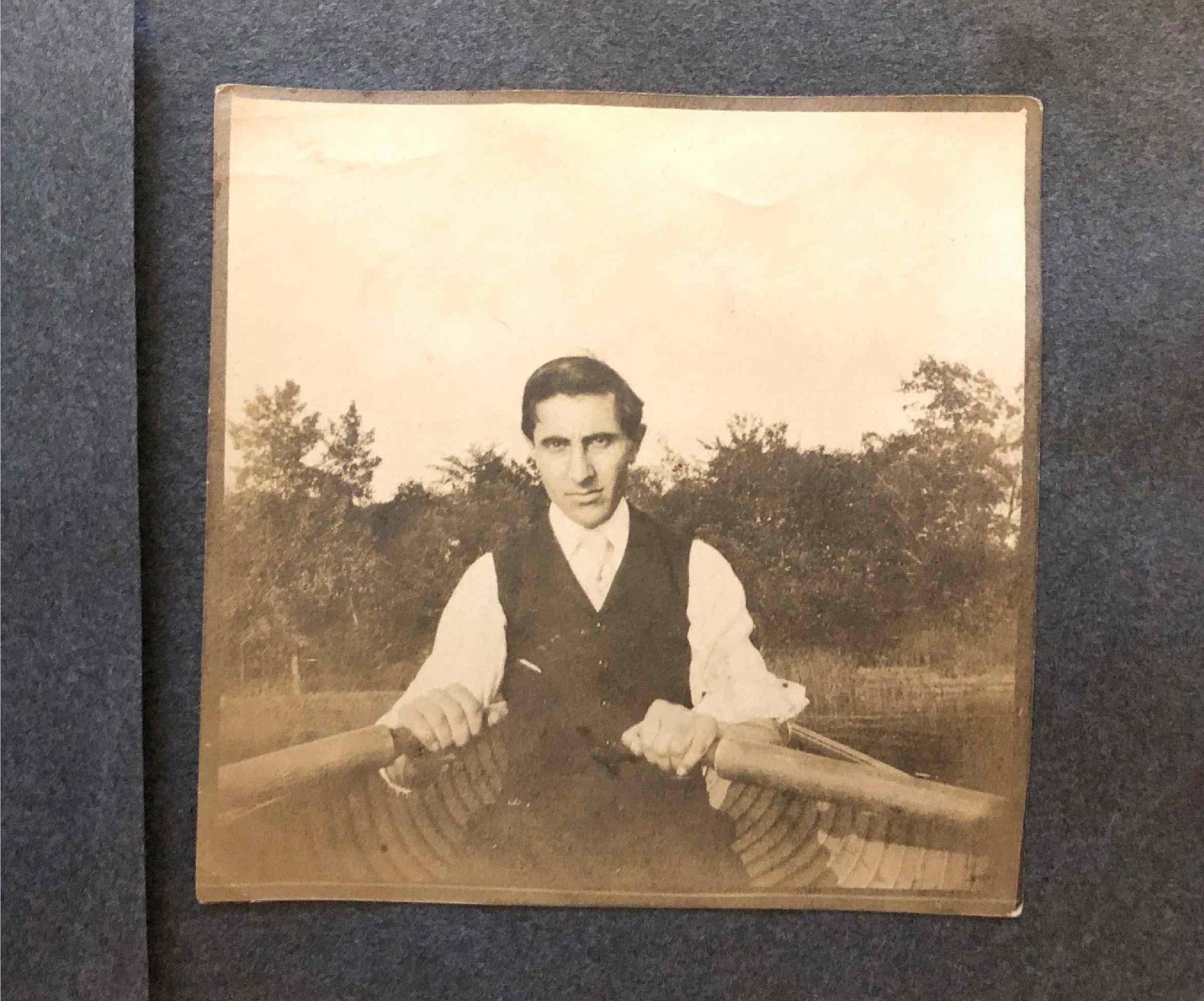

After difficult early years, Hohannes and Tevrez’s children came to enjoy a bourgeois lifestyle, spending most of the year in their apartment in Morningside Heights and summering in Saratoga Springs. Their son, Frank, attended Columbia, a favorite university of the Armenian diaspora. A handful of letters sent to Hagop’s wife, Priscilla (1895-1915) show the family’s ongoing ties with Armenian communities both in Constantinople and the Central Valley of California, where the promise of cheap agricultural land was drawing many migrants. The brothers encouraged several other members to immigrate before and during the 1915-23 genocide. All the while, they invested heavily in side ventures. A series of letters detail Hohannes and Hagop’s later years, after they moved to Fresno to oversee 120 acres of grapes and prunes. Hohannes and Hagop bought up suburban development land in northern New Jersey, Minneapolis, Fresno, and San Francisco, all of which were a constant source of litigation. Upon Hohannes’ death in 1928, his estate was worth $78,513, nearly $1.2 million adjusted for inflation.

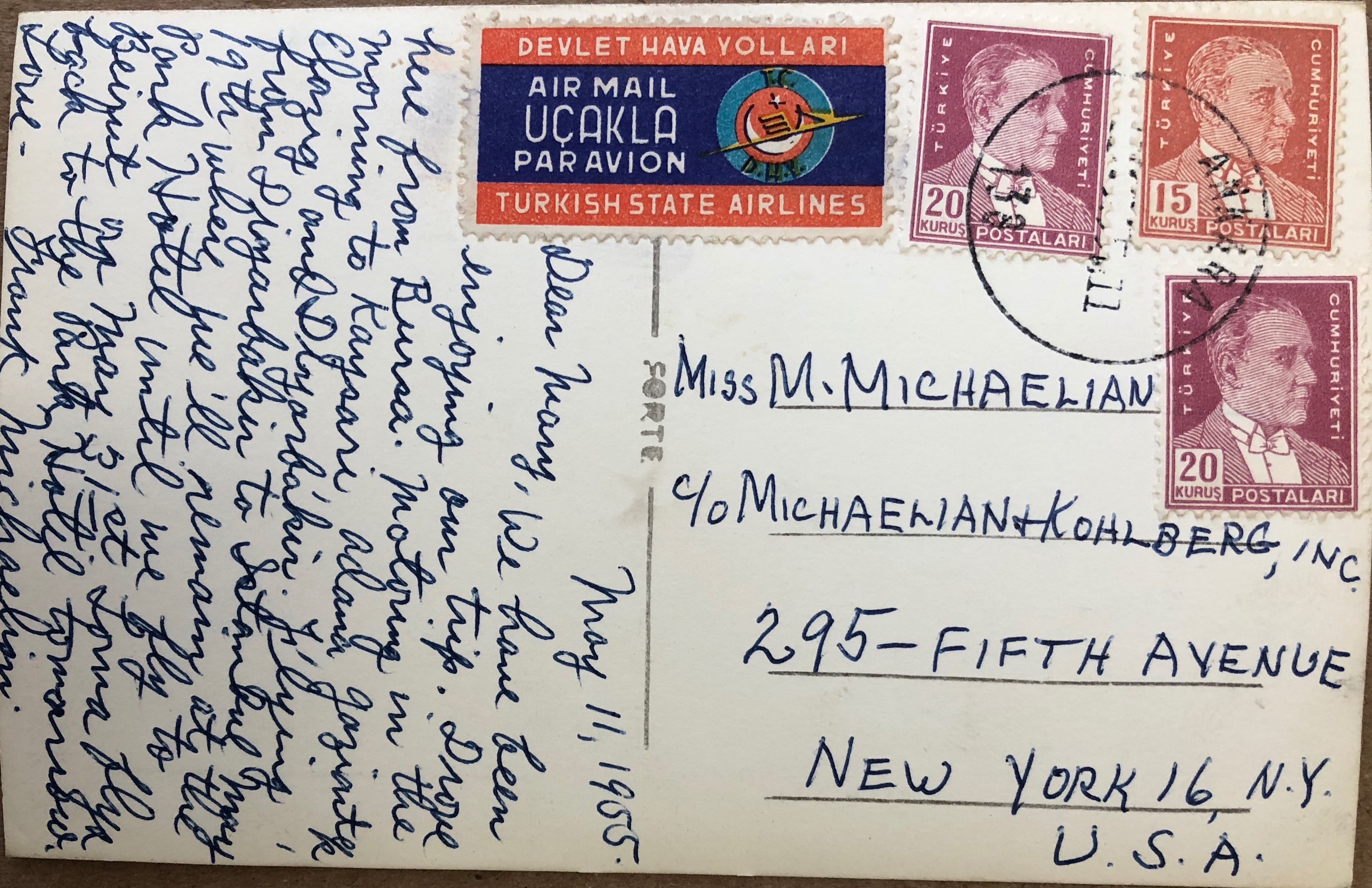

The second generation of the American Michaelians pursued several conscious strategies of assimilation. The first was in language use. Although Hohannes and his brothers continued to conduct the family business primarily in Armenian, only Florence and Frank, who followed his father into the rug business, spoke it fluently. Founding the independent firm Michaelian & Kohlberg in 1921, Frank established factories in Iran, China, and eventually North Carolina to produce rugs for the American market. It does not appear that Hohannes’ American-born daughters Mary (1899-1998) and Edith (1905-40), my great-grandmother, spoke much Armenian at all; all their letters to their mother are in English. Florence, who would travel widely in the fashion industry and study several languages, kept obsessive English diaries from a young age (“The ‘Titanic’ left England on either Thursday, April 11th, or Friday on its first voyage to America,” she writes in one foreboding entry).

Marriage offered another path towards assimilation. Hohannes and Tevrez’s children chose non-Armenian spouses; Frank married Cornelia Blomberg (1902-84), from an Ashkenazi Jewish family, in 1922, while in 1928, Edith eloped eloped with my great-grandfather George L. King (1904-1947), an Anglo industrialist from Syracuse. Finally, there were politics. Garabed’s son, Edwin G. Michaelian (1906-83), used Michaelian & Kohlberg as a springboard into office, serving as Mayor of White Plains (1950-57) and as Westchester County Executive (1958-73). A ubiquitous figure in New York Republican circles during the 1960s-70s (“Mr. Republican”), Edwin used his connections with the Nixon administration to secure a lucrative contract for Frank to re-carpet the Oval Office. Edwin lent his support to members of other Huysenig families running for office as Republicans in the northeast.

It is worth asking why the second generation of the Michaelians felt such a strong pressure to assimilate in the first place. Most of them continued to work in industries dominated by Armenians; they had recognizably Armenian last names and were active members of the Armenian Evangelical Church. One answer lay in the Passport Office clerk’s physiognomic description of John Michaelian’s face in 1891. Although contemporary boosters of the Armenian community lavished praise on their ability to learn English, marry outside the community, make money, and get educated, none of these factors were sufficient to prove what federal law demanded of all migrants to the U.S. in the early twentieth century: white skin.

For all that M. Vartan Malcom (whose 1919 Armenians in America offers the first sociological study of the community) could extoll Armenians as “the Anglo-Saxons of the East,” Armenians were still migrants from the Asian continent. The silence about his Armenian roots that George King sought to fill at the end of the twentieth century was the product of his family’s negotiation with federal immigration law at its beginning.

***

For Armenians, proving white racial identity became crucial to ensuring their ability to stay in the United States. Between 1898 and 1925, federal courts laid down a conflicting series of rulings to determine who had the right to American citizenship. Responding to increasingly paranoid Anglo attitudes towards migration, the federal government began sporadically suing to denaturalize citizens under the terms of the Naturalization Acts of 1790 and 1870, which respectively limited naturalization to free whites and blacks (only one case is known where a defendant claimed to be black). Although immigration from much of east Asia had been outlawed as early as 1875, United States Code did not explicitly ban immigration from the Asian continent as a whole—including from the Ottoman space—until the Immigration Act of 1917. Ottoman immigrants challenged prevailing definitions of ‘whiteness’ or European ancestry; the vast majority were Christian, literate, and many were fair-skinned. ‘Defending’ the Ottoman Christians was a common pretense for western intervention during the empire’s final century and, after all, American missionaries abroad had actively facilitated their emigration.

Federal courts labelled Armenians ‘white’ in two major decisions in 1909 and 1925. In the first case, In re Halladjian (1909), decided by the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Massachusetts, Judge Francis C. Lowell declined to overturn defendant Jacob Halladjian’s naturalization in response to a challenge by the U.S. Attorney’s office. Rejecting the U.S. Attorney’s claims that Armenians were biological “Mongolians,” the court instead affirmed Halladjian’s white racial identity through a rambling disquisition on Armenian history, language, and Christianity, finally deferring to the precedent set by government officials who had assumed Armenians were white for decades.

Thirteen years later, the U.S. Attorney’s office in Portland, Oregon attempted to have this ruling overturned in light of the Supreme Court’s decision in United States vs. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923). Thind had canceled the naturalizations of migrants from the Indian subcontinent, even if they claimed to actually be of “Aryan” or “Caucasian” background. This decision effectively overturned much of Halladjian’s reasoning: mythopoetic claims of descent, the court ruled, were insufficient to prove ‘whiteness’ for immigration purposes. In United States vs. Tatos Cartozian (1925), the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon would affirm that Armenians qualified as whites under a different standard of what it called “common understanding.” Rather than descent, courts should determine ‘whiteness’ by behavior and physical appearance. The crucial factor underlying the claim to citizenship, John Tehranian writes, was a “performance of whiteness;” by making oneself act and look ‘white,’ the law would affirm one was. (To a point: the court’s standard still excluded dark-skinned migrants like Bhagat Singh Thind, no matter how ‘white’ they acted).

Cartozian was a Pyrrhic victory. It permanently granted Armenians a coveted spot in America’s racial hierarchy, and offered migrants already in the United States a clear path for naturalization. But at the same time, the new Immigration Act passed in the previous year virtually banned further Armenian immigration. If it were the Turks who took the Armenian homeland away, the American judiciary extended a Faustian bargain. Embracing American modernity meant relegating Armenia to the past.

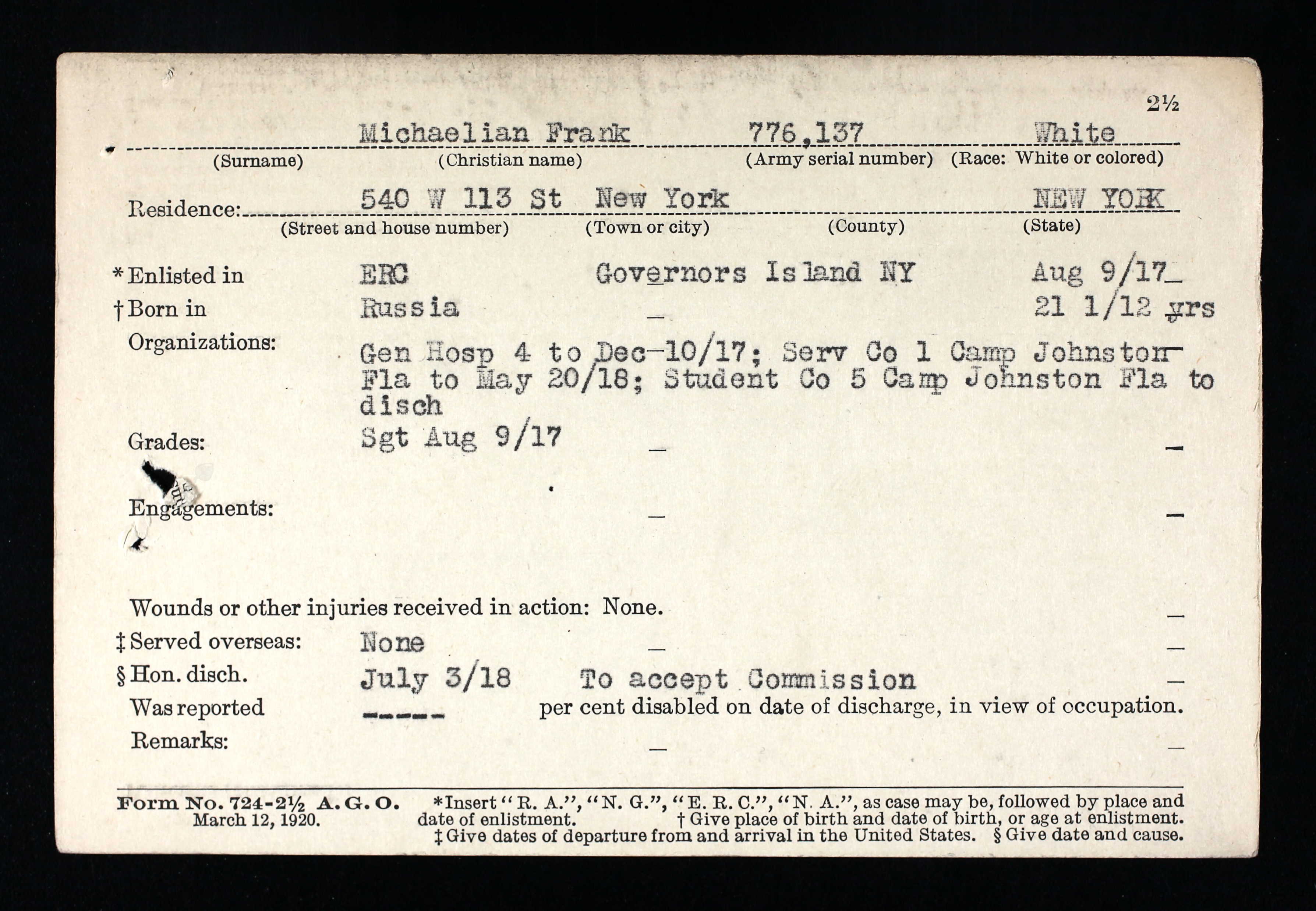

This transaction is visible in how Frank Michaelian consciously manipulated his presence in government documents as the denaturalization sweep was heating up. A generation prior, the dark-eyed, dark-skinned John Michaelian had faced no objection to his naturalization in 1891 and no problem reentering the United States with his new family after his long absence. Both the New York State Census of 1905 and the federal census of 1910 list the family as white. But Frank’s encounters with the federal government were less innocuous. A memorandum produced by the legal counsellors Osborne & Cornish in 1917 lays out how Frank was unable to secure a commission as an Army officer in 1917 until he could prove his American citizenship. Ultimately the problem was dispelled: in measured prose, his lawyers would retrace John Michaelian’s migration narrative to prove that Frank was a natural-born American citizen immune from challenge. Frank was never at real risk of deportation, but the menace was there: the ongoing slaughter in Anatolia was regularly in the headlines.

It was at this time that Frank Michaelian began to strategically alter his ancestry on paper. Whereas most documents show John, Frank, and Florence’s birthplaces as “Turkey,” Frank’s Army papers give his birthplace as Russia. Filling out a passport application in cursive in 1924, Frank correctly identifies his birthplace as Harput. But then he crosses out the printed oath he was required to sign as a “NATURALIZED AND LOYAL CITIZEN” and writes, in block capitals, “NATIVE.” Even sixty years later, his obituary begins with the statement—exceptional given his unaccented English, Anglo name, military service, and patronage ties—that he was an American citizen by birth. The government’s attempt to render Tatos Cartozian stateless lingered in Frank Michaelian’s consciousness decades after it had failed in the courts.

Malcom’s repeated comparison of Armenian Americans with Japanese Americans—whom he also presents as a model minority—makes it understandable why Frank Michaelian would be so defensive. Although the law now counted the Michaelians ‘white,’ their physical appearance continued to present a space where other ‘white’ viewers could project what they wanted to see.

A contrasting picture can be seen in two representations of second generation members of the Michaelian family. First is a photograph of my great-grandmother Edith dating to the early 1930s, taken and hand-tinted by my great-grandfather George. Edith, who even in black-and-white photographs appears fair-skinned, is presented with light brown hair, piercing green eyes, stenciled eyebrows, and a trendy bob; her skin is porcelain. On the other hand, a caricature of Edwin Michaelian sketched by the artist Vigiani in 1951 presents him in profile with dark eyes, a short chin, jet black hair, and a giant, hooked nose. Caricature relies on stereotypes, and it is debatable whether the artist meant to make Edwin look ‘Armenian;’ the representation more accurately seems to convey an imagined physiognomy shared with other second-generation ‘ethnic’ tri-state politicians. Still, despite their status as safely ‘white’ ethnics, the second generation of the Michaelians retained signs of their precarity that could be—but ultimately were not—activated at any moment. Only at the end of the twentieth century did the situation become inconsequential enough for my grandfather to ask where his own dark skin came from.

***

I doubt when my grandfather died in 2001 he had any idea what a cypher for whiteness Armenian identity was about to become in America. At least on the internet, the people most likely to cite Halladjian or Cartozian are antagonists of the race-bending Kardashian clan, whose embrace of African American culture is focalized through their self-conscious exteriority to whiteness. On the other hand, for Twitter’s resident ethno-nationalists, the logic of Halladjian lives on. Armenians are a foundational part of the west, and therefore white; everyone else, and especially the Turks, are not. If your racial politics are frozen in 1925, the fact that Turks or Iranians also have mythologies of essential whiteness will not convince you that race is a legal and social construct.

But for the early Michaelians themselves, and countless others like them, the math was simple. Assimilating into whiteness meant being allowed to stay, and it was an easy decision to make. Neither was it insincere, as critics of Armenian assimilators sometimes imply. When twelve-year-old Florence was furiously journaling about appearance, manners, and the news, she was remaking herself in the image of a white American teenager in the same way as the German, Czech, and Russian girls she went to junior high with were. At the same time, the significance of naming the family trust document after the home village Huysenig escaped nobody; when Frank wrote Mary an oblique postcard from nearby Elazığ on a business trip in 1955, it was obvious that he was making a pilgrimage. In their act of being both/and, the Michaelians created a type of circumscribed Armenianness for their own consumption, one that would easily have escaped the understanding of my grandfather in his youth. His rediscovery of the past towards the end of his life left him searching for what it all meant.

1 comment