Afshin Marashi is Professor and Farzaneh Family Chair in Modern Iranian History at the University of Oklahoma, where from 2011 to 2020 he also served as the founding director of the Farzaneh Family Center for Iranian and Persian Gulf Studies. He is the author most recently of Exile and the Nation: The Parsi Community of India and the Making of Modern Iran (University of Texas Press, 2020). His previous books include Nationalizing Iran: Culture, Power, and the State, 1870-1940 (University of Washington Press, 2008), and the volume (co-edited with Kamran Aghaie) Rethinking Iranian Nationalism and Modernity (University of Texas Press, 2014).

Afshin Marashi is Professor and Farzaneh Family Chair in Modern Iranian History at the University of Oklahoma, where from 2011 to 2020 he also served as the founding director of the Farzaneh Family Center for Iranian and Persian Gulf Studies. He is the author most recently of Exile and the Nation: The Parsi Community of India and the Making of Modern Iran (University of Texas Press, 2020). His previous books include Nationalizing Iran: Culture, Power, and the State, 1870-1940 (University of Washington Press, 2008), and the volume (co-edited with Kamran Aghaie) Rethinking Iranian Nationalism and Modernity (University of Texas Press, 2014).

- Your new book, Exile and the Nation: The Parsi Community of India and the Making of Modern Iran, is an exciting transnational history of the 20th century. The book has it all, from murder mystery to poetry to philanthropy and more. Can you tell us about it?

What I’ve tried to do with this book is to add a new layer of complexity to the history of modern Iranian nationalism. Among the most ubiquitous themes of 20th century Iranian culture are the themes of neo-classicism and the renewal of interest in Iran’s Zoroastrian heritage. In Exile and the Nation, I’ve historicized the process by which this took shape, but instead of looking at state-led projects, or the influence of European ideas of nationalism, I’ve looked to the cultural and intellectual encounter with India’s Zoroastrian community to explain how these ideas evolved.

The book argues that the reciprocal encounter between the Parsi community of India — especially those in the city of Bombay (or Mumbai) — and the community of modern Iranian intellectuals was key to this history. The Parsis had mostly emigrated to South Asia in the medieval period. By the 19th century they had become a prosperous minority in the context of India’s British colonial history. It was in this period that they began a series of philanthropic and quasi-missionary efforts to reach out to Iran, to both re-connect with the remaining Zoroastrian communities inside Iran, and to establish reciprocal exchanges with Iranian intellectuals.

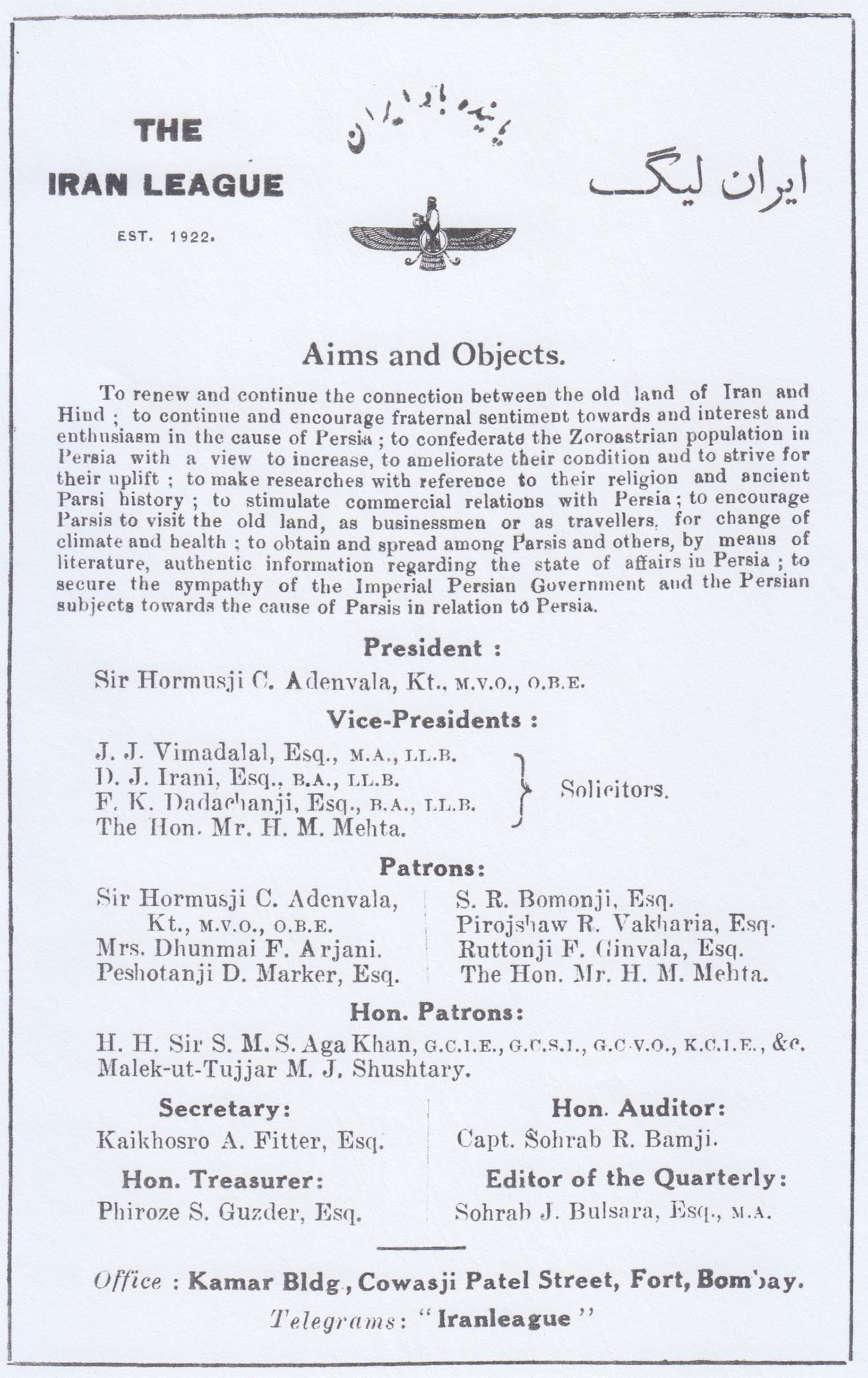

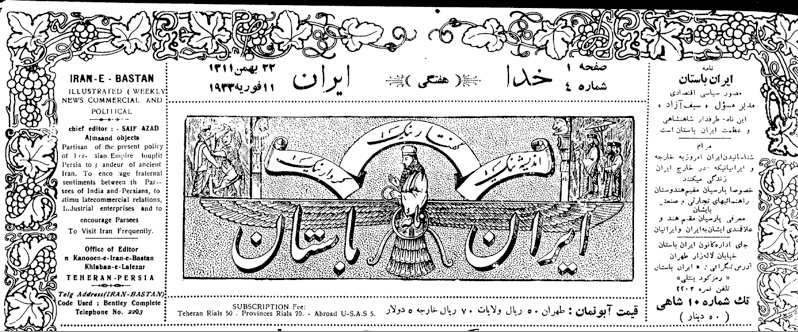

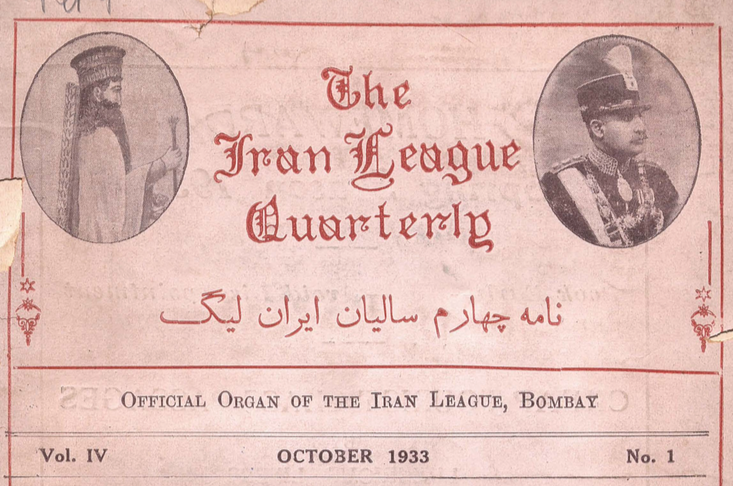

Most of the book focuses on the 1920s and 1930s, which is the period that represents the high-point of this exchange between the Parsis and the Iranians, although the roots do go back earlier. Bombay-based Parsi civic organizations facilitated much of this exchange, in particular an organization known as the Iran League (established in 1922). They were involved in multiple philanthropic efforts, including building schools, hospitals, and orphanages in Kerman, Yazd, and Tehran. They also published an important bi-lingual English and Persian journal, the Iran League Quarterly documenting their efforts.

You mentioned the “murder mystery” element that’s part of chapter 1, which is a good way of describing that chapter. There’s perhaps a film noir element as well. When I was a student, my favorite works of history were always books that were conceptually sophisticated yet readable. Nikki Keddie’s (my PhD advisor) al-Afghani biography worked that way, as did Albert Hourani’s Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age, and Eric Hobsbawm’s Age of Empire. These are some of the key texts that shaped my approach to thinking and writing. The source material that I found for the book was extremely rich, and so I’ve tried to write Exile and the Nation in a way that is both conceptually sophisticated, while also being engaged in an imaginative — or perhaps cinematic — exercise that paints a vivid portrait of the Parsi-Iranian exchange. Hopefully it makes the book readable.

- For those familiar with your research, we know that you have had an interest in bookshops and the movement of books. How did that interest play into the making of your own book, Exile and the Nation?

One of the ways that the pre-Islamic revival grew inside Iran was through the production and circulation of a new genre of books published by the Parsis in India. Part of what I’ve tried to do in this book, and in my 2015 IJMES article about the history of bookstores in Tehran, is to develop a way of doing intellectual history that is more than just a history of ideas. Ideas are more than disembodied abstractions, they have a material history that is contained in books. Tracing the movement of books is one way of thinking about ideas as part of the social worlds where they circulate.

As I was doing the research for this book, I quickly learned that the books published by the Parsis in Bombay were making their way to specific bookstores in Tehran. The books themselves tell us, not only who the publishers were, but often tell us where they were sold. This led me to see if I could figure out who owned these bookstores, where they were located, what their history was, and who the customers were. I was surprised how much of this I was able to map. Nile Green’s Bombay Islam has a chapter about Bombay-based Persian-language publishers who produced books for export, and my interest began there, but I wanted to figure out what happened to these books once they made their way to Iran. It became sort of a research scavenger hunt. The short answer is that they migrated to the bookstores inside Iran, and were read by a new social strata of Iranian readers. In this way, my IJMES article can be read as an appendix to Exile and the Nation.

- I love how you emphasize the importance of the movement and mobility of people as well. Could you talk a little bit about the mythical importance of migration versus the zigzagging between Iran and India in the 19th and 20th centuries?

There’s at least two things to say about that. First, all of the characters whose lives I document in Exile and the Nation travelled extensively during the course of their lives. This was made possible by new technologies of mobility, especially steamships within the Indian Ocean world. By the 1920s and 30s, it was relatively easy to travel by steamer between Bombay or Karachi and the Persian Gulf ports of Bushehr, Khorramshahr, Basrah, and the newly built port of Bandar Shahpur. Road and rail construction were also central to new possibilities of mobility. Of course there had always been a history of mobility between Iran and South Asia, but by the interwar period it became much easier. For Parsis, the new possibilities of mobility even spurred a new culture of “heritage tourism” to visit Iranian archaeological sites. There is actually a whole history of tourism that needs to be written in the field of Iranian studies.

The second point to make about mobility is that the kind of travel that I’m describing is very modern, not only in terms of its modalities, but also in terms of how the experience of displacement and connection were understood. You can’t really experience the modern notion of “exile” without first understanding the idea of a national homeland. The mythical idea of a medieval Parsi exodus to India only begins to take shape as Parsis begin to think about their history through a modern lens. Even the 16th century text Qesseh-ye Sanjan, which is a poetic rendering of the Parsi exodus from Iran to India, was likely understood in a very different way when it was written than how it was later understood in the 19th and 20th centuries. Alan Williams has made this argument. So we should distinguish between the experience of mobility and migration as it was understood in the pre-modern period, from the way those modalities of travel were experienced in the modern-national age. Both produced forms of meaning, but they were of different types.

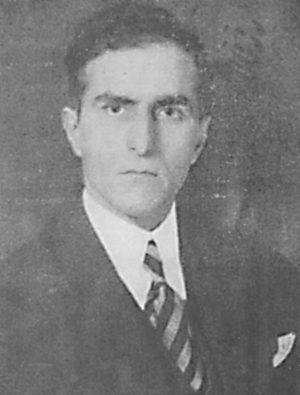

- Each of the chapters is centered around a person. As a historian, I find that I sometimes develop relationships with the people in my research, and it was very sweet for me to see how each of these people – Kaykhosrow Shahrokh, Dinshah Irani, Rabindranath Tagore, Ebrahim Purdavud, and Abdulrahman Saif Azad – anchored your book in their own way. How did you come to pick these people as the stars of your book?

The short answer is that there was a mixture of considerations, some of them historical, and some of them practical. I wanted to select figures who were key to the history that I’m studying. The biographical approach is sometimes criticized, but I think if it’s done well it can be illuminating. I’ve tried not to focus exclusively on the interiority of the subjects, but on how their lives intersected with one another and with the social worlds that they inhabited.

I also selected the central figures to help make the book’s central argument, which is that the Parsi-Iranian exchange produced a wide range of possibilities for Iranian nationalism, from a liberal-ecumenical form to a more exclusionary and right-wing variety. The lives that I document in the book illustrate this idea, and might help us to reconsider some of the alternative histories of Iranian nationalism that have perhaps been forgotten. I think uncovering this history might also have implications, not only for Iran’s past, but for Iran’s future as well.

- At the same time, I’m reading through the chapters and I’m thinking, where are the women! We hear about Madame Cama, a few aunts and other women – could you tell us a little more how they fit into the Parsi community activism and transnational ties to Iran?

School for Girls in Tehran. Source: ILQ, NYPL.

If there is one thing that I hope grows out of this book, it’s that the book will inspire a fuller reconsideration of Madame Bhikaiji Rustom Cama. She was a central figure, not only in the Parsi-Iranian exchange, but also in the broader history of a “proto-Third Worldism” that took shape during the early decades of the 20th century. She hailed from a prominent Parsi family, was a leading anti-colonial activist in London and Paris, and was remarkably successful in building coalitions between different expat groups in Europe, including Indians, Iranians, Arabs, Russians, Germans, Irish, Turks, as well as Marxists and anarchists. Nawaz Mody has published an important article about the life of Madame Cama, but there’s not much else. In Exile and the Nation she plays a key role as the person who politicized Ebrahim Purdavud, and is probably the first Parsi that he ever met, in Paris, sometime around 1910. She was a remarkable figure, but she was also somewhat exceptional, since the political and intellectual histories of both Parsi nationalism and Iranian nationalism were steeped in patriarchy during that period.

There are other important women in the book as well. Armen Ohanian, the Armenian-Iranian writer and actress, and pioneer in modern Middle Eastern queer culture, also makes an appearance. She lived a fascinatingly transnational life that also intersected with the community of Iranians in Paris in the years before WWI. Like Madame Cama, Armen Ohanian’s life also deserves further study. You mentioned “the aunts,” these were relatives of Kaykhosrow Shahrokh who had migrated to India in the mid-19th century, married into prominent Parsi families, and encouraged Parsi philanthropy towards Iran. They helped their nephew to make his way to Bombay for his education. There are numerous other examples of this as well. The other key female figure is Ratanbanu Bamji Tata. She was from the family that owned one of the most successful industrial firms in colonial India, and she was responsible for providing the financial resources to build the famous Anushiravan School for Girls in Tehran. This and other similar schools helped to produce a new generation of women who became part of an emerging Iranian middle class. There’s a whole transnational history of Parsi-Iranian gender activism that certainly deserves a more detailed study than what I’ve been able to provide in this book.

- So much of the scholarship on Iranian nationalism is linked to the Persian language. Many of your principal characters wrote either treatises on religious texts, poetry, translations, and more in multiple different languages. How does a transnational lens shed light on how languages take on multiple valences?

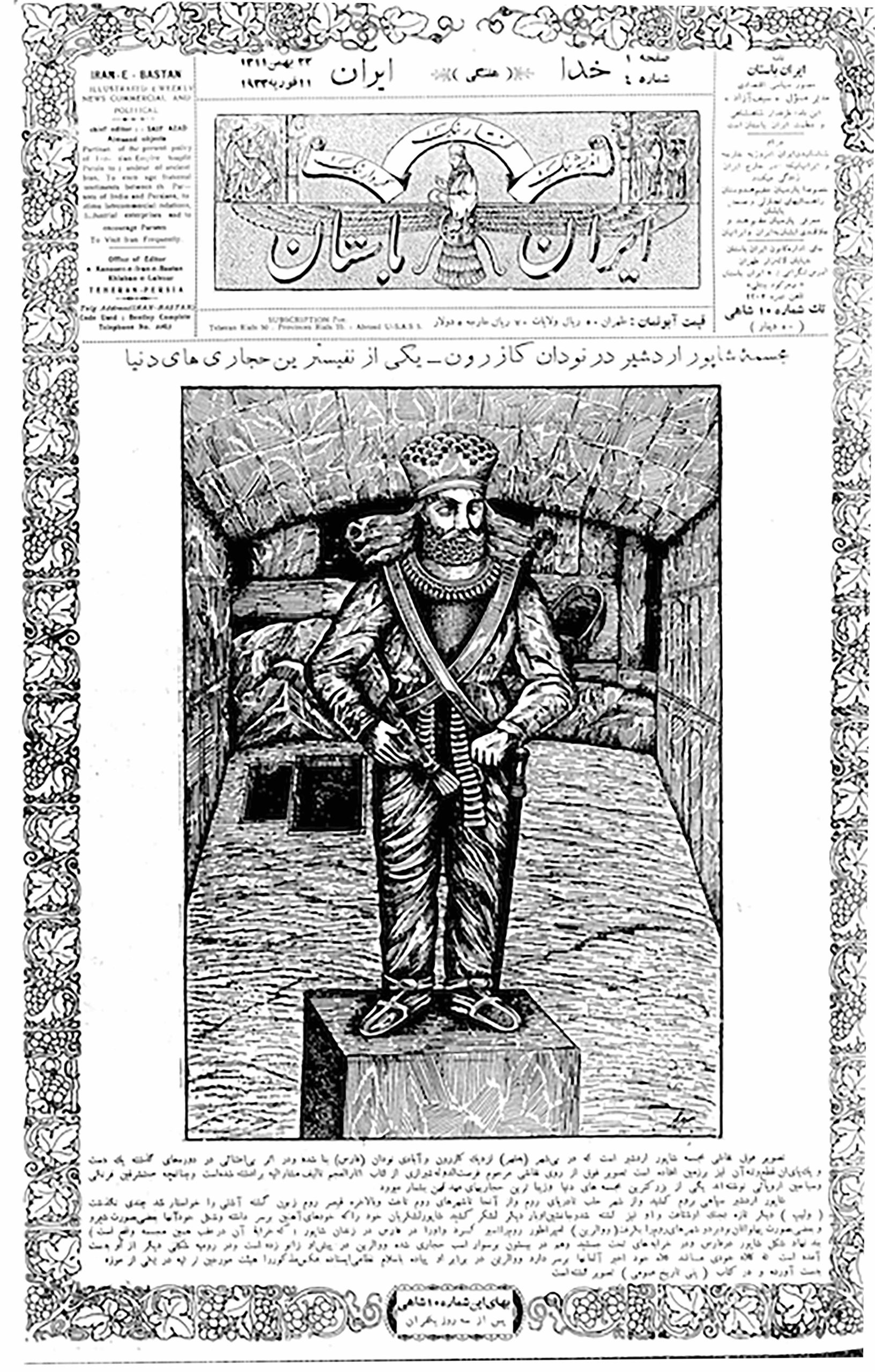

35. Source: IISH.

Iranian history does not solely exist within the linguistic purview of Persian. In the case of the Parsis, it’s Gujarati that is the most important language for understanding Parsi history, not Persian. I haven’t used Gujarati sources for this book, because the field of Iranian studies doesn’t really encourage someone to pursue knowledge of a language like Gujarati. I’m glad that this now seems to be changing, and a scholar like Dan Sheffield at Princeton is exceptional as a person who uses both Persian and Gujarati sources.

We can say the same about Urdu, which as a “South Asian Studies” language is not a language that we in Iranian studies have been generally encouraged to pursue. My colleague at the University of Oklahoma, Alexander Jabbari, is working on a book manuscript that explores the intersections between Persian and Urdu. Mana Kia’s new book, Persianate Selves, also questions the geographies of Persian. These examples shouldn’t be the exceptions. The intersection of the Persian and Russian linguistic worlds is another area that needs further study.

You mentioned translation, which I also consider in Exile and the Nation. As with books as material objects, we can also understand the circulation of ideas by tracing their movement through languages. But translation isn’t simply about the “transmission” of an idea from one language to another, translation also affects the possibilities of meanings that those ideas can express. For example, Ebrahim Purdavud’s New Persian translations of the Avesta not only made the Zoroastrian texts knowable to modern Iranians, but those translations rendered those texts into the poetic idiom of the Persianate literary tradition. I’ve tried to touch on this in the book, but there’s much more that needs to be figured out. As I try to argue in the book, Iranian intellectual history is not simply about orientalist discourse dominating Iranian intellectuals. The history of translation in a transnational context might help us to see something else going on, something more productive and creative, and maybe more interesting.

- Reading your book about how these diasporic populations fostered such strong ties to Iran in the early 20th century was interesting to read from my own vantage point, as an Iranian-American from a different diasporic center, Tehrangeles. Do you see parallels between these diasporic centers, Los Angeles and Mumbai?

Exile and the Nation might be an allegory for Tehrangeles. Like you, I grew up in Los Angeles, in the San Fernando Valley (or “Valley-abad” as we call it). The more I learned about the Parsis, the more familiar their story appeared to me. The Parsis developed a diaspora culture shaped by a memory of displacement. Iranians in Los Angeles have similarly produced displaced Iranian cultural spaces within Los Angeles. It might seem strange to say, but contemporary multicultural Los Angeles is not unlike polyglot Bombay of a century ago.

You can see this in places like bookstores, food markets, and restaurants. I remember as an adolescent going to Sherkat-e Ketab on Westwood Boulevard, the most famous bookstore in Tehrangeles (which sadly closed down a couple of years ago). I also spent a lot of time there in the 90s, when I was a graduate student at UCLA. Whenever I would walk into that bookstore I always felt like I was walking into a cultural space that was defined by a certain version of displaced Iranianness. As a young person it was strange and intimidating, but I remember asking myself: How did all of these books get here? The origins of Exile and the Nation probably goes back to trying to answer that question. I had a similar feeling of displaced Iranianness when years later I sat in one of the “Irani cafés” in Mumbai. The Iranians in LA are probably becoming more and more like the Parsis of a century ago. I think that might be a useful idea for readers to keep in mind while reading the book.

- Exile and the Nation is a trailblazing book in Iranian studies. Much of the transnational studies in modern Iranian studies look to “the West,” but you looked east to India. What are your thoughts on the evolution of the field of modern Iranian studies?

I think we are at a critical moment in the evolution of Iranian studies. There has definitely been a turn towards “the global” in the broader field of historical research, and we are seeing this take root in Iranian studies as well. Part of what this means is that approaches shaped by national history and narrowly defined area studies are being replaced by new ways of finding connections between histories. In modern historiography, the narrow focus on European influence has also obscured the history of South-South connections that are still quite unexamined for the modern period.

What I’ve tried to do with Exile and the Nation is to reconfigure the history of Iranian nationalism as a movement that emerged from a much more complex set of entanglements stemming from the Indian Ocean world, the decline of the early modern Persianate system, and the empowerment of a new Parsi-centered understanding of Iranian history and culture. I’ve tried to approach the subject in a way that is both trans-regional (with South Asian Studies) and trans-temporal (with early modern history). Once we move beyond the limiting frameworks of national history, area studies, and Eurocentric histories, an entire world of new research possibilities opens up. Exile and the Nation is just one example of this new approach to the field. Houri Berberian’s Roving Revolutionaries, and Arash Khazeni’s, Talinn Grigor’s, and James Pickett’s forthcoming books are other examples of this in the modern field. There are some exciting dissertations in the works as well. The field needs more voices and more perspectives. We have so much work left to do, so much to think about, and so much history yet to write. I’m eager to see what comes next.

International, 1907. Source: IISH.