The following is a guest post by Gayané Ghazaryan, a freelance journalist based in Yerevan, Armenia. Her work focuses on memory and narratives of gender, social and cultural issues, and she is a graduate of the American University of Armenia, where she wrote her thesis about the history of Radio Yerevan. Follow her on instagram @gayanegigi.

***

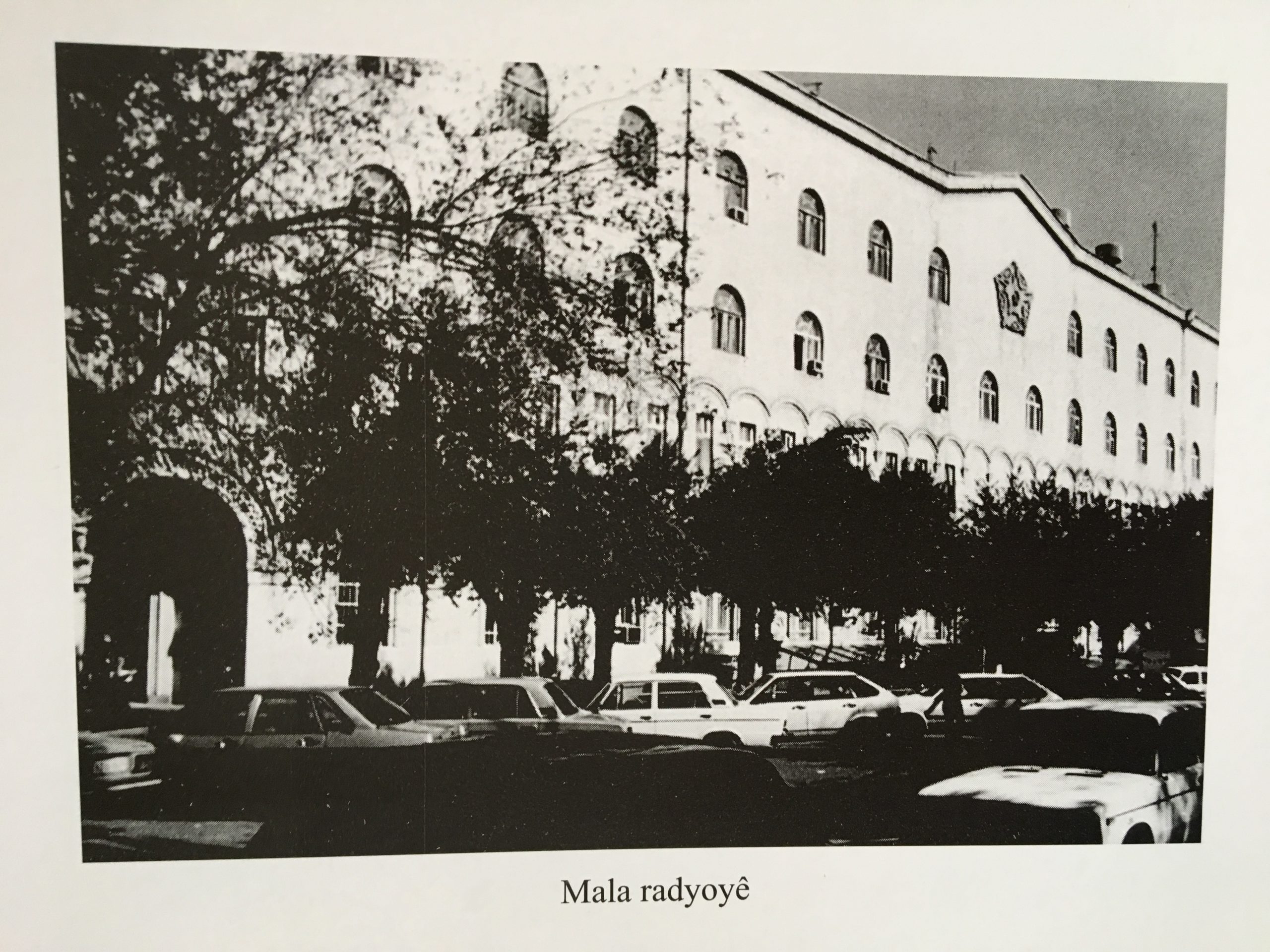

Yêrêvan xeberdide! (Yerevan is speaking). These were the first Kurdish words aired from the Public Radio of Armenia in 1955. Known as Radio Yerevan beyond Armenia’s borders, it helped connect thousands of Kurds to their culture in the second half of the 20th century, when Kurdish identity was denied and cultural expression prohibited across the Middle East.

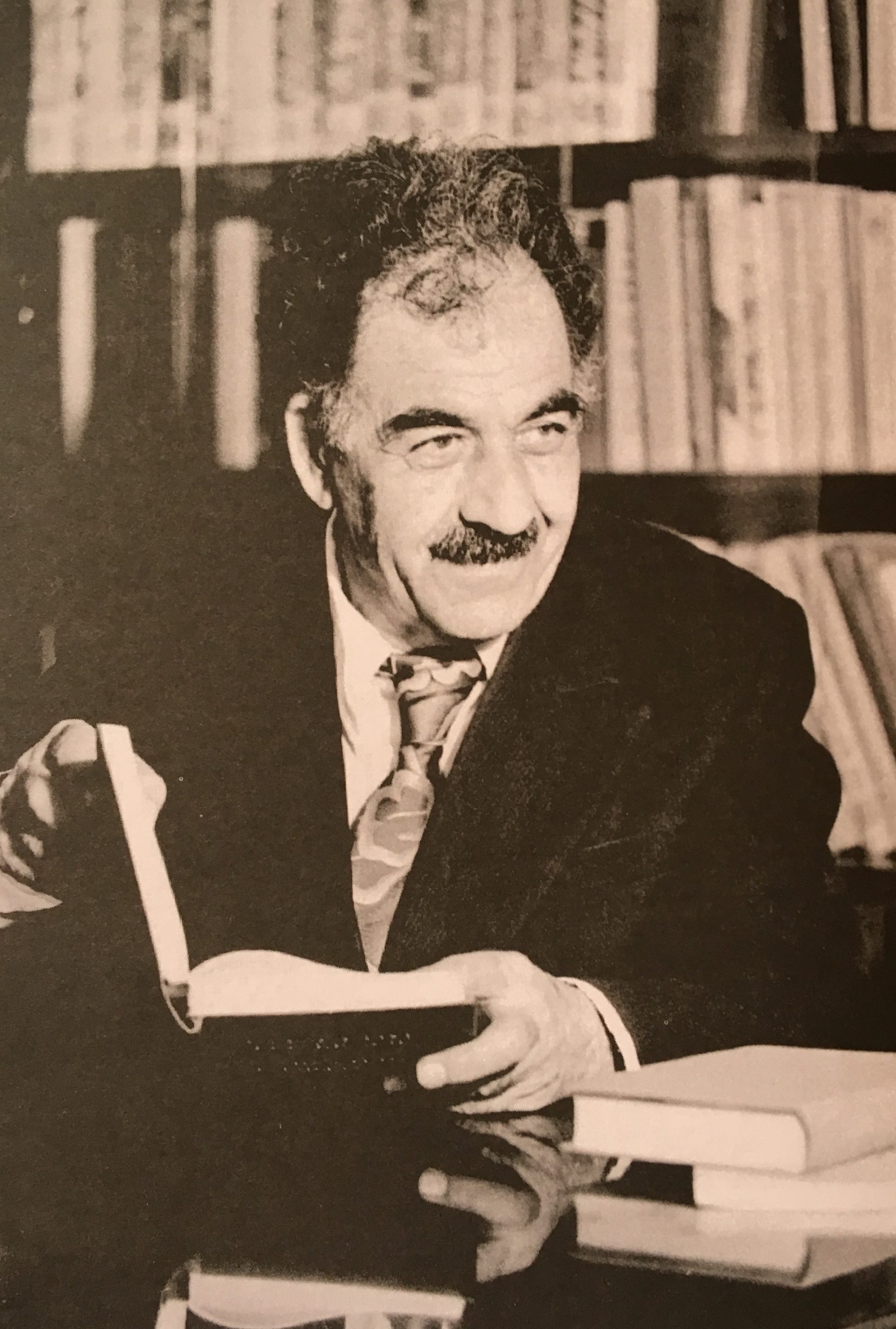

While the decision to have Kurdish programs was made by the Central Administration of the Former Soviet Union, Yerevan kept on “speaking” and “singing” in Kurdish thanks to Casimê Celîl, his family and their collaboration with local Kurds and Armenians. The history of Radio Yerevan’s Kurdish broadcasts is interwoven with the story of the Celîl family.

Living in Yerevan for most of my life, I never knew there were Kurdish Radio broadcasts until 2017 when a close friend from Istanbul shared a Kurdish song with me called Leylo Xanê, which was recorded in Yerevan decades ago.

To me, this song was a window through which I would later uncover the vast cultural work that Kurds in Armenia had done. It was also one of the rare stories related to Armenian-Kurdish relations that wasn’t about inter-communal violence but rather a story of collaboration and friendship. This article, based on oral history interviews and conversations with Cemîla Celîl, Casimê Celîl’s daughter, explores her family’s work toward the preservation and development of Kurdish folklore in Armenia and beyond.

From Kars to Yerevan: The Story of Casimê Celîl

Cemîla Celîl’s father, Casimê Celîl, was the first to move to modern-day Armenia. A poet, translator and educator, Casimê was born in 1908 to a family of Ezidi (also called Yazidi) Kurds in the village of Ghzl-Ghula (Armenian: Ղզլ-Ղուլա; Turkish: Kızılkule) in the Kars oblast (then part of the Russian Empire) and was a child of the “orphan generation.” He was about 10 years old, when his family decided to escape the persecution of Armenians, Ezidis, Assyrians, and Greeks across the Ottoman Empire. Known as the Armenian Genocide, the killing claimed more than 1.5 million lives and involved members of many different ethnic and religious groups, including Yazidis like Casimê Celîl.

By the time Casimê Celîl arrived at the Ottoman-Russian border near the modern-day state of Armenia, his entire family had been killed, except for his paternal aunt, who helped him cross the river. He found refuge in the orphanage of Gyumri (then called Alexandropol), which was also home to thousands of orphaned children who were survivors of the Armenian Genocide. After spending his teenage years in the orphanages of Gyumri and Stepanavan, like many of his peers, Casimê moved to Yerevan to work and study. At the time, the Bolshevik Revolution had successfully transformed the Russian Empire into the Soviet Union, and Yerevan had become the capital of the newly-established state of Soviet Armenia.

Casimê always showed interest in education, especially literature. He never forgot his native Kurdish, but quickly learned Armenian and Russian during his time at the orphanage and later continued his education in Tbilisi and Baku between 1927-1931. Returning to Yerevan, he enrolled in the State Pedagogical University of Armenia. This was also the period when Casimê started writing poetry. His first poems and translations were published in the local Kurdish newspaper, Rya Teze (“new path” in Kurdish). Written in the Kurdish Kurmanji dialect, as well as Armenian and Russian, Casimê’s literary work was characterized by lyrical warmth and sincerity with many poems dedicated to love and nature. By the time he graduated from the Pedagogical University, he was already a member of the Writers’ Union and, as his daughter notes, “he had excellent relations with the Armenian intellectuals of the time.”

Casimê became the head of Radio Yerevan’s Kurdish department in 1954, shortly before the first official broadcast on January 1, 1955. Initially, the programs were scheduled three times a week, for only 15 minutes and were meant as a propaganda tool of the Communist Party to disseminate a political agenda to Kurdish communities across the border.

However, Casimê saw the radio as an opportunity to revive Kurdish music and make it accessible to a broader audience at a time when Kurdish culture was largely banned across the region in the different countries where Kurds lived. Subjected to attempts to forcibly assimilate them into the dominant Turkish, Arabic, or Persian cultures of their respective nation-states, Radio Yerevan became one of the few outlets for Kurdish culture. “Not only were his intentions controversial at the time, they also required additional resources the Radio administration couldn’t afford.”

“In Soviet times, in the 1930s, people could get prosecuted for a single word. Back then, Stalin had already passed away, but the fear was still there,” notes Mrs. Celîl. Nevertheless, after getting rejected once in trying to expand the radio’s cultural broadcasts, Casimê tried again, eventually convincing the head of the Radio to play Kurdish songs at the end of each program for two minutes. “All my father needed was that permission, some tape and a sound engineer. He promised to take care of everything else.”

Once Casimê got the permission, he headed to the town of Talin in the western Aragatsotn region of Armenia which had become home to many refugees during the years of the Armenian Genocide. There he asked Şamilê Bako, a Kars native who was also an Ezidi, to come to Yerevan with him to record the first piece. Bako was delighted by Casimê’s offer. Not only did he agree to play a Kurdish tune on the duduk, he also named it Casko, which is the affectionate diminutive for Casimê.

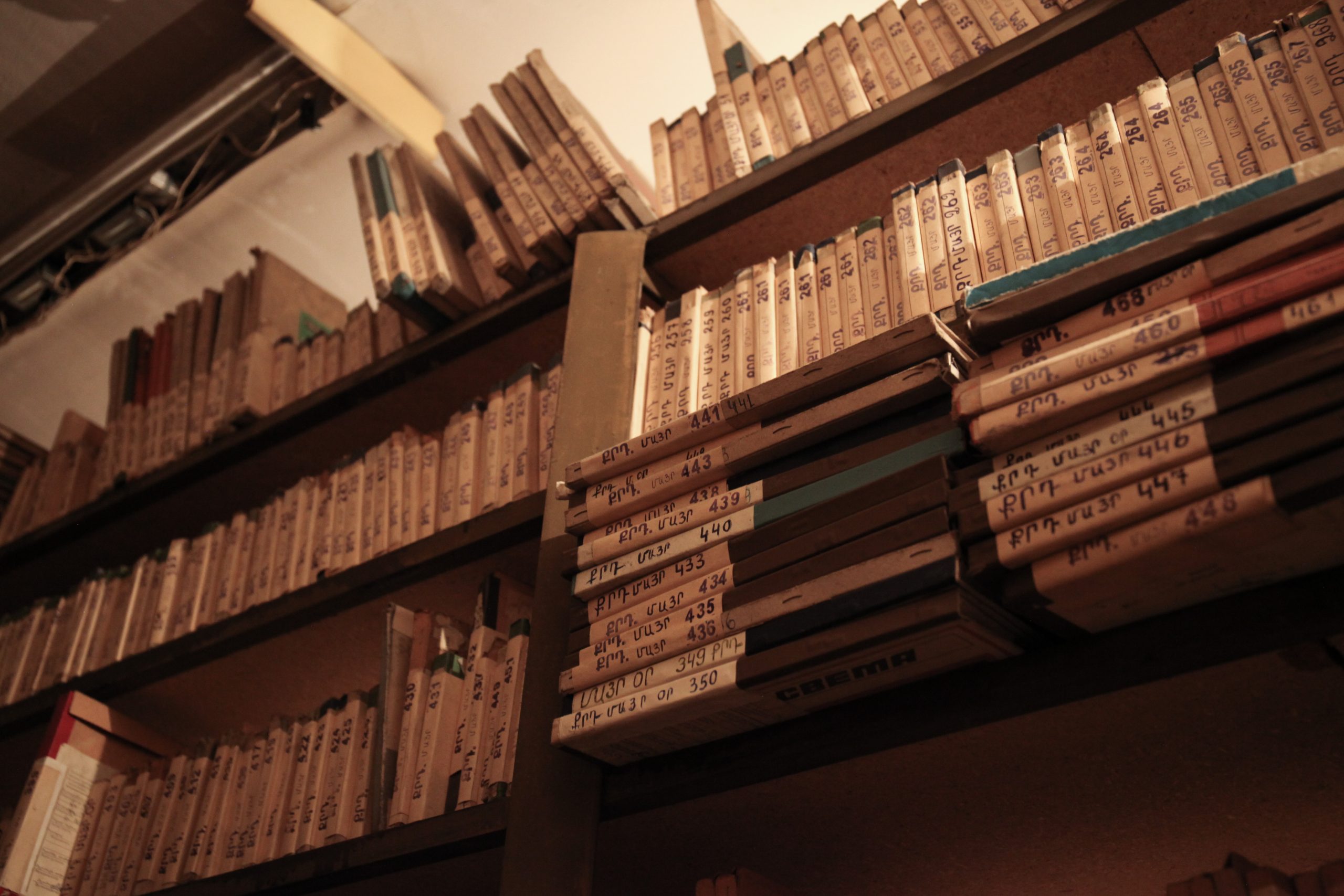

Casimê, who worked as the head of the Kurdish broadcasts from 1954 until 1964, left a legacy of over 700 original recordings, setting the foundation for the Kurdish audio archive at the Radio. In Mrs. Cemîla’s words, “It was unheard of.” No such thing had happened in any other Soviet republic. Thanks to Casimê’s efforts, a huge Kurdish audio archive was established, the first one in the history of the Soviet Union. Although they achieved a lot, they always faced restrictions. Mrs. Cemîla notes that they often had to translate the songs into Russian or Armenian to get approval for their content. Songs with religious context were forbidden. “But I’d always find a way to air them if they had beautiful melodies,” says Mrs. Cemîla, noting that it wouldn’t have been possible to keep the programs going without the support of her father’s Armenian colleagues, for which she was immensely grateful.

Although there’s no data on the exact number of the listeners, the many letters Mrs. Cemila would receive weekly, spoke about the popularity of Radio Yerevan’s Kurdish broadcasts across Armenia and beyond its Western border. “Many elderly people would ask their grandchildren to write letters to the radio staff to express their gratitude and ask for a specific song to air for the upcoming programs,” Mrs. Cemila recalls. When the broadcasts transcended the Armenian-Turkish border in the early 1960s, the broadcasts brought Kurdish tunes to those who were deprived of the right to study their mother tongue.

“People were giving up whatever they were doing and were listening to the radio,” said Ahmet Kaya, a medical doctor and one of the founders of Koma Amed, who grew up listening to the broadcasts. “Back then radios were still rare as not everyone could afford them. Kaya recalled how they would gather at someone’s house, who had a radio at home and would listen to the programs as a community.”

Home: A Living Memory of The Past

Finding Kurdish musicians and dengbêjs (Kurdish singer-storytellers) to perform wasn’t too difficult for Casimê, who had grown up with many of them in the orphanage and always stayed in touch with the Kurdish community across Armenia, who were mostly refugees concentrated in the Armavir and Aragatsotn regions of Armenia. The difficult task was finding accomodations for them, which, with the lack of financial assistance from the Radio administration, was left entirely on Casimê’s and his family’s shoulders.

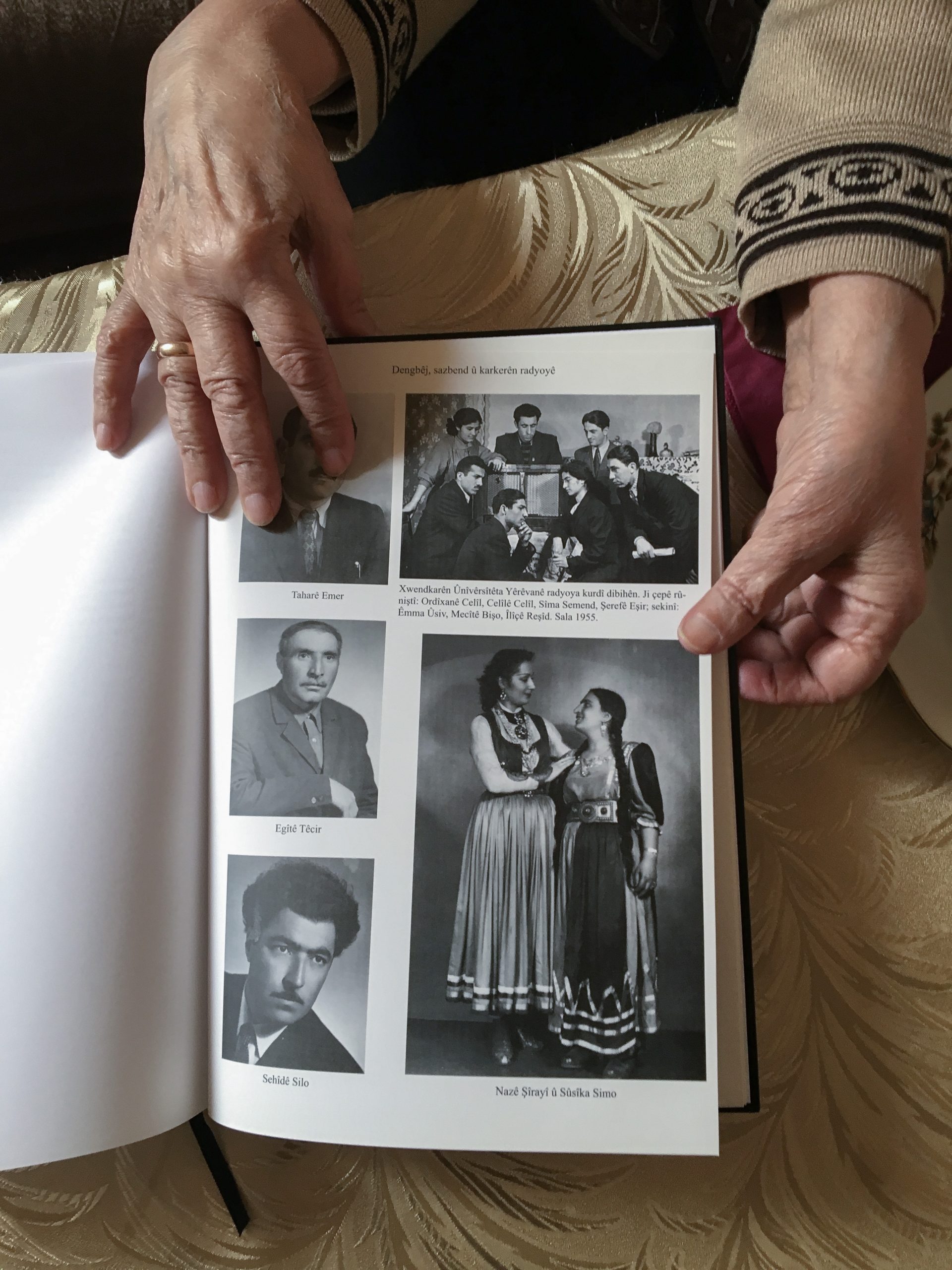

When I first stepped into the living room of Mrs. Cemîla’s modest apartment in downtown Yerevan, the first thing that caught my eye was the large image of a group of women dressed in traditional Kurdish garments, hung above the couch.That picture, the many little photographs peeping at me from Mrs. Cemîla’s bookcase, the huge portrait of her parents along with the old-fashioned black cassette player next to her couch made me feel like I was in a museum, in an archival room rather than someone’s living-room. And indeed, for decades, those walls absorbed the stories, voices and melodies of all the people who made Radio Yerevan’s Kurdish programs possible.

“Our apartment had turned into a villager’s home,” Mrs. Cemîla recalled with a feeling of longing in her voice. Most musicians and dengbêjs were from villages and to make sure they didn’t have to worry about their accommodation while in Yerevan, Casimê always hosted them in his apartment. “They came to our home bringing the smell of manure and tondir with them, the smell of the village.”

At the Radio studio, Casimê did everything to make the villagers feel comfortable. To many of them the radio studio was an intimidating place at first. The equipment and the recording process were new to them. Most of them were Yazidi and Muslim Kurds, who could not speak a word of Armenian. To comfort them, Casimê would say, “Please, feel at home here. Imagine you’re in your house, playing. I’ll be on the other side of the window if you need anything.”

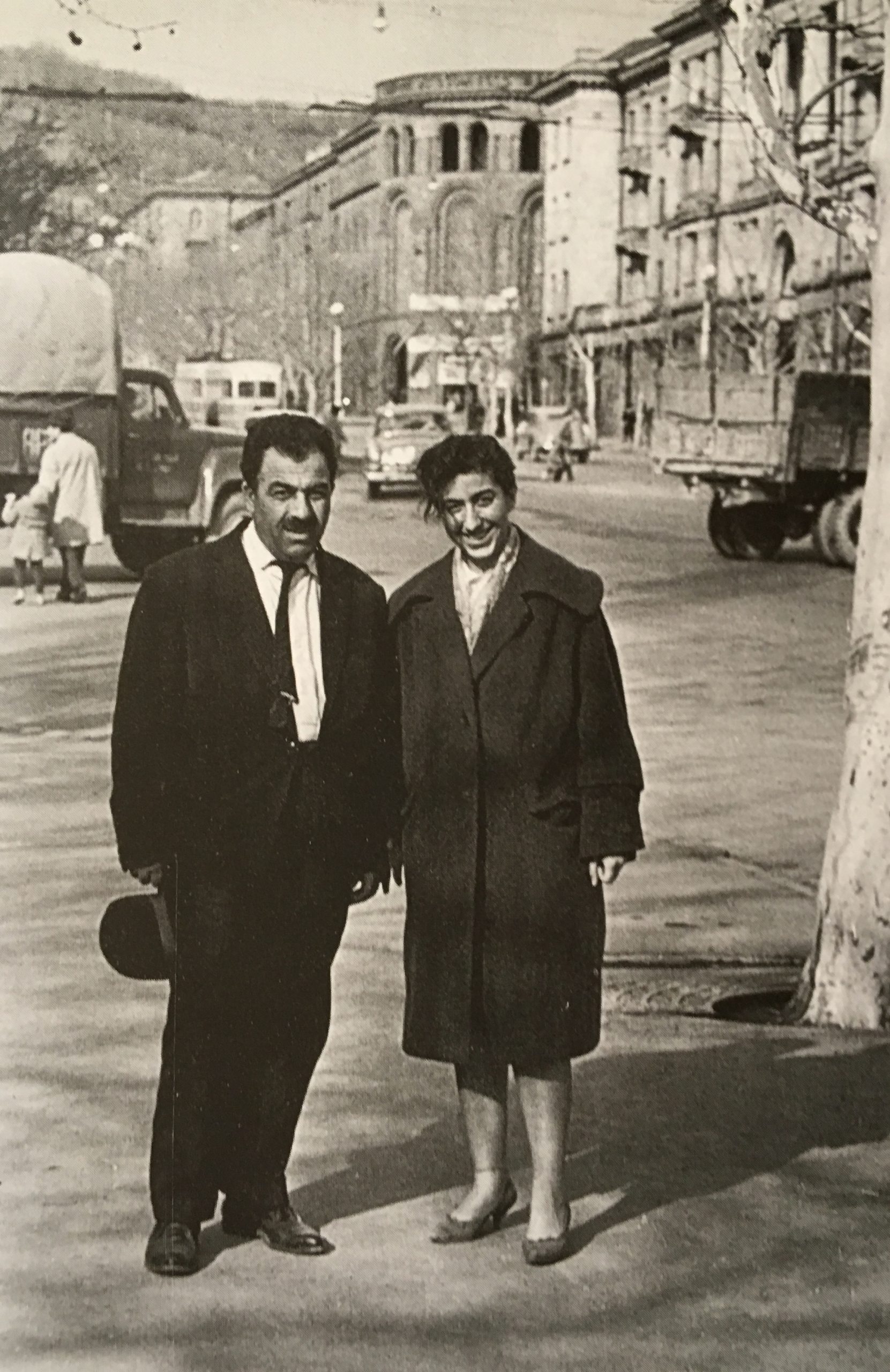

In their apartment, the roles were swapped. Now, it was Khanoum’s (Mrs. Celîl) turn to make sure their guests were comfortable and had everything they needed. Khanoum, who also grew up as an orphan, was always hospitable and compassionate toward others. She would make the villagers’ beds and cook for them. Mrs. Cemîla recalls many times when the apartment got overcrowded with guests and there was even shortage of food. Khanoum would tell her children, “That’s alright. We can eat bread and cheese today. They are guests. We should treat them kindly.”

Looking back at those years, Mrs. Cemîla says proudly, “My father taught us the value of national songs and music, my mother taught us how to treat people.” The apartment and the memory of it meant so much to Mrs. Cemîla that even after getting married, she kept visiting it almost every day. After her husband passed away, she moved back to her family home and to this day she spends most of her days working in that very living-room.

Carrying on Casimê’s Legacy

With their family home turned into a cultural hub, Mrs. Cemîla and her siblings – Celîlê, Ordîxanê and Zînê – grew up with Radio Yerevan’s Kurdish programs. It was only natural that they would continue their father’s legacy. Ordîxanê Celîl, who was the first anchor of Radio Yerevan’s Kurdish broadcasts, studied philology and was the Kurdish studies chair at the University of Leningrad, one of the most prominent and prestigious universities in the USSR. In 1931 Freyman founded a seminar on Kurdish linguistics within the faculty of Language of Leningrad University. And in 1959 the Kurdish Department or the Kurdish Section (Kurdskiy Kabinet in Russian) was founded within the Institute of Asian People of USSR’s Sciences Academy in Leningrad by Hovsep Orbeli, a Soviet public figure and academic of Armenian descent.

Ordîxanê frequently traveled in Armenia and visited Kurdish communities in Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan as well to conduct ethnographic research. Many of these communities were formed as a result of various waves of deportations from Iran in the 17th century while others fled religious persecution in the Ottoman Empire. In the spring of 1958, he went to Iraq with the assistance of Mustafa Barzanî, to collect folklore from the Kurdish peshmerga (Kurdish: پێشمەرگه , Pêşmerge: members of the armed forces in the Iraqi Kurdistan. The word peshmerga translates to ‘those who face death’).

Ordîxanê and his younger brother Celîlê, a historian and a current member of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna, authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on Kurdish folklore and history, which then got translated into Russian and Lithuanian by their sister, Zînê Celîl. Their works, such as Stranên Lîrîkên Gelêrîyên Kurd (Kurdish Lyrical and Folkloric Songs, 1964), Zargotina Kurda (Kurdish Folklore, 1978) and Zargotina Kurdên Sûriyê (Folklore of Kurds in Syria, 1989), contributed to the further development of Kurdish studies beyond the Soviet Union.

While her siblings concentrated mostly on the linguistic, literary and historical aspects of Kurdish culture, Cemîla Celîl devoted herself to the exploration of Kurdish folk music. She officially joined the Radio in 1967 to take care of the musical archive as well as manage the broadcasts. As a musician and musicologist, Mrs. Cemîla came up with new arrangements for old songs as well as designed and coordinated her own programs. The Music Mailbox (known as Երաժշտական փոստարկղ [yerazhtakan postarkgh] in Armenian) was the most popular one. “People would tell their grandchildren to write letters to us [many elderly were illiterate], asking to play their favorite songs,” she told me with a warm smile in her eyes. The Music Mailbox wasn’t merely a medium for entertainment, but served an educational purpose as well. “I’d speak about classical composers, Armenian composers, especially those who had some connection to Kurdish music, for example, Komitas, Aram Khachatryan, Spiridon Melikyan and Srbuhi Lisitsyan.”

Besides her main work at the Radio, Mrs. Cemîla conducted field work as well. Traveling to various regions of Armenia, she wrote down and recorded Kurdish folk songs on her portable recorder. In the 1990s, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, Armenia suffered immense economic hardships that were reflected in various aspects of the country’s socio-cultural life. The increasing poverty forced thousands of people to emigrate. Almost the entire staff working for the Kurdish department, 13 people, left the country as well.

Among those who stayed were Mrs. Cemîla and Keremi Seyyad, one of the hosts, who was also actively involved in the production of the programs. Looking back at those years Mrs. Cemîla said, “Those were challenging times. Villagers wanted to come to Yerevan to record their new songs, but we didn’t even have a tape to record on. I didn’t want to let them down and would either re-use some old ones or record them on my cassette player.” Mrs. Cemîla worked at the Radio for 35 years, until 2002, enriching the archive with thousands of new recordings, waiting to be digitized soon. She also has hundreds of recordings in her personal archives which she regularly updates to this day.

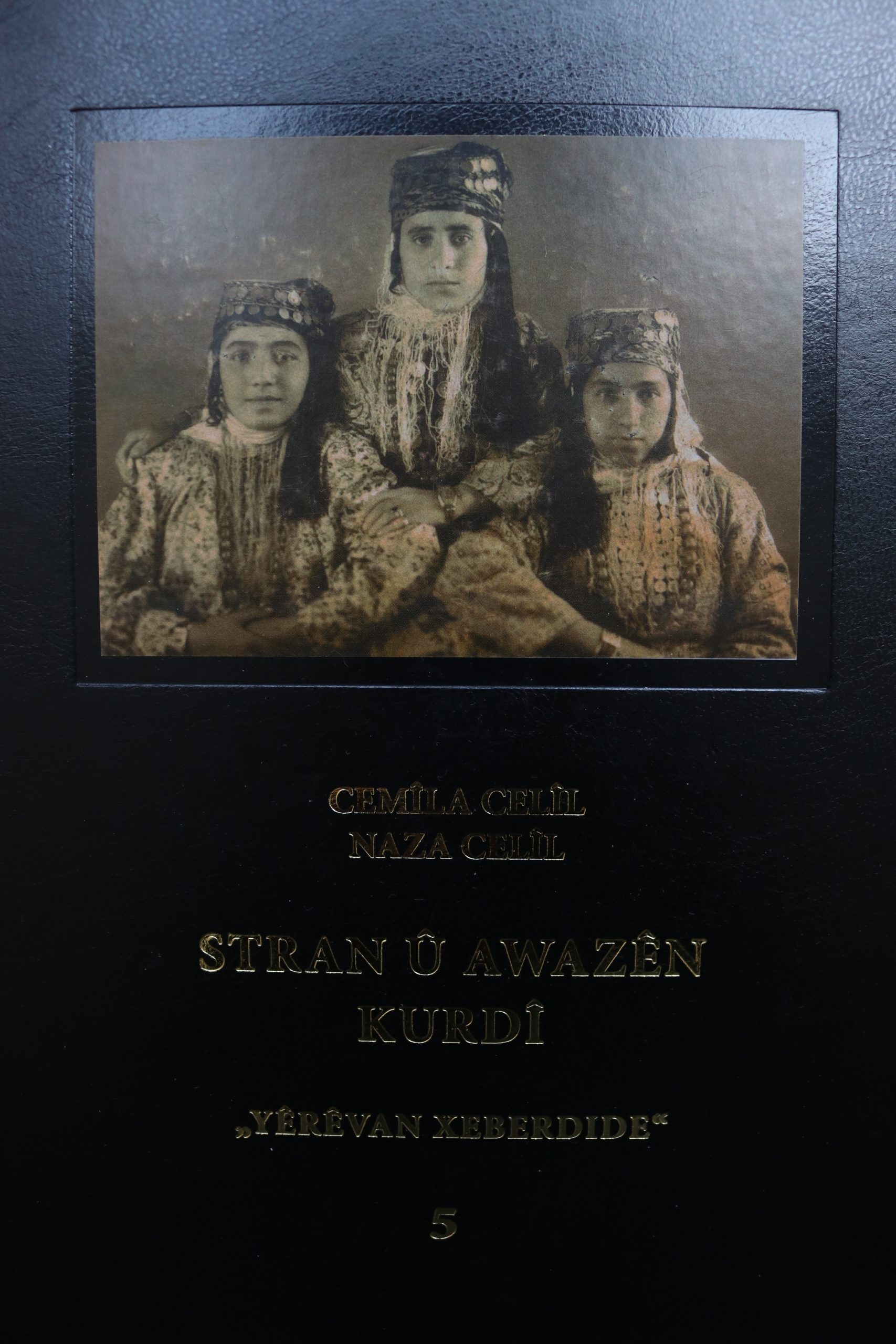

Many of the songs have been digitized and have been turned into CDs as part of Stran û Awazên Kurdî (Kurdish Songs and Melodies), a five-volume book by Mrs. Cemîla and her daughter, Naza Celîl. The first three volumes were published between 2002-2006 in Yerevan, while the 4th and 6th ones were published in Vienna with the support of Celîlê Celîl. Each volume of the book presents the songs played on Radio Yerevan, their lyrics and notes, transcribed and arranged by Cemîla as part of her fieldwork. At the age of 81, Cemîla Celîl is currently working on the 6th volume of the book with no intention to retire from the cultural work she’s been doing for decades. “I’m doing this for my people, for the generations to come,” she told me several times, “so when I’m no longer here, the knowledge, the culture won’t be lost.”

References

Ghazaryan, G. (2020). The Kurdish Voice of Radio Yerevan. American University of Armenia.

Scalbert-Yücel, C., & Ray, M. (2006). Knowledge, Ideology and Power. Deconstructing Kurdish Studies. European Journal of Turkish Studies, (5). doi:10.4000/ejts.777

Blum, S., & Hassanpour, A. (1996). The Morning of Freedom Rose up’: Kurdish Popular Song and the Exigencies of Cultural Survival. Popular Music, 15(3), 325-343.