The following is a guest post by Timur Khan, a Dutch-Pakistani researcher with a master’s degree in Middle Eastern Studies from Leiden University. He is interested in the history of Peshawar and Afghans in the 18th and 19th centuries and previously wrote about Pashtun identity for Ajam. Follow him @timurkhan97.

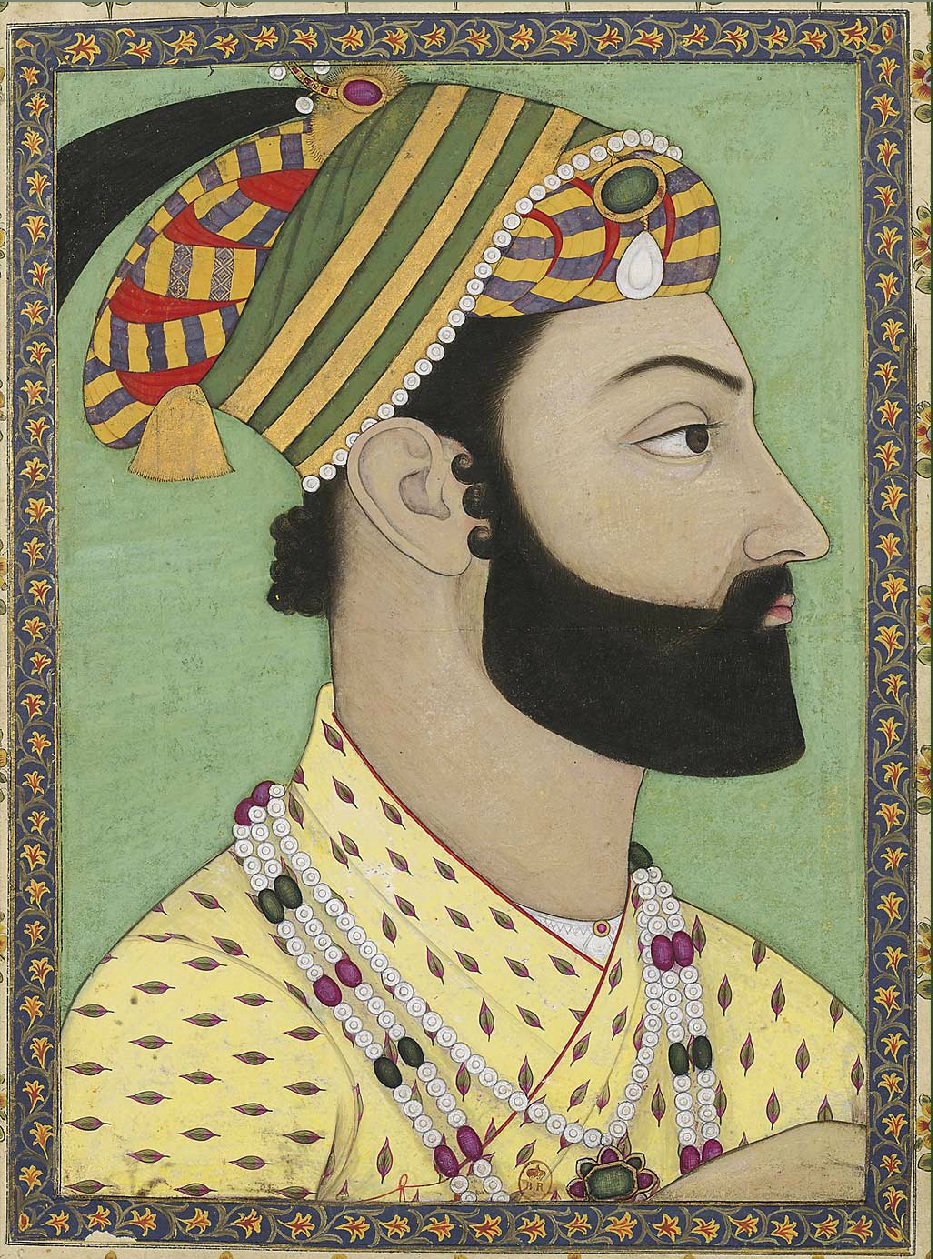

In early 1757, Ahmad Shah Durrani, one of the most powerful rulers in South and Central Asia, made a woman the ruler of vast swathes of territory in northern India. Granting her traditional badges of power like a “tiara, aigrette, [and] cloak,” Ahmad Shah is said to have exclaimed: “Hitherto I have style you my daughter, but from today I shall call you my son,” and given her the princely epithet Sultan Mirza. This woman, known as Mughlani Begum – ‘Begum’ being a title denoting female nobility – was hardly the only woman to wield political power in early modern South Asia. However, she remains one of the least-discussed and remembered.

The story of Mughlani Begum’s involvement in the momentous political struggles of 18th-century India has appealed to some modern scholars and storytellers as a story of female empowerment. A 1979 film directed by Surjit Singh Sethi emphasizes her affairs as an expression of freedom. The cover illustration of a serialized Urdu novel by Muhammad Rafiq Dogar depicts her as a warrior, armed and confident. Entries about the Begum find their way into works highlighting notable historical women of the region.

Nonetheless, casting Mughlani Begum as a heroine is not always easy. She lacks the ever-popular anti-colonial credentials of someone like Lakshmi Bai, the Rani (queen) of Jhansi, who fought the British East India Company in the climactic 1857 rebellion, now considered a national War of Independence in modern South Asia. In contrast, Mughlani Begum allied with Ahmad Shah, an Afghan ruler who invaded north India repeatedly; indeed he seems to have named her his ‘son’ after she accompanied him to the brutal sacking of Mathura, a Hindu holy place. While Lakshmi Bai’s various biopics are full of glory for the queen, Ahmad Shah is portrayed as a bloodthirsty villain, including most recently in the Indian blockbuster, Panipat. And while other women often mentioned as politically influential in early modern Indian history were attached to the Mughal court – like Nur Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal, who is buried at the Taj Mahal – or ruled wealthy territories for years, like Begum Samru, Mughlani Begum only achieved great heights of power for a brief period in the 1750s and 60s.

These complexities are why the story of Mughlani Begum is worth telling. History is full of men who were imprisoned, died, or otherwise failed to hold power. Many of these, like the Mughal prince Dara Shikoh, receive as much attention as their more successful contemporaries. As a shrewd politician who survived a period of immense upheaval when many others perished, Mughlani Begum deserves the same. Hers is by no means a story of mere failures.

What her story offers is a chance to round out our understanding of women in South Asia’s political history, not only as a matter of exceptional heroes and rulers, but also one of contenders who fell short of their ambitions – just as we accept in male-dominated political history. Lacking as it does the luster of the Taj Mahal or the ‘War of Independence,’ Mughlani Begum’s story allows us to move past mythologized representations of the past as grand battles between good and evil, and instead shows us the murky, often violent, realities of what it means to wield power.

Mughlani Begum’s struggles for control

Mughlani Begum’s life is principally narrated by an enslaved man in her employ, Tahmas Khan, in his Qiṣṣa-yi Ṭahmās-i Miskīn, or Ṭahmās-nāma. This autobiography is a personal, literary work, not a historical chronicle. What we are dealing with is more Tahmas’ personal retelling of the Begum’s life than a self-narration or a scholarly attempt to relay information. Few details of her background, even her age, are offered: she enters the narrative upon the death of her husband in 1753, the Durrani governor (nawāb) of Punjab, Moin ul-Mulk.

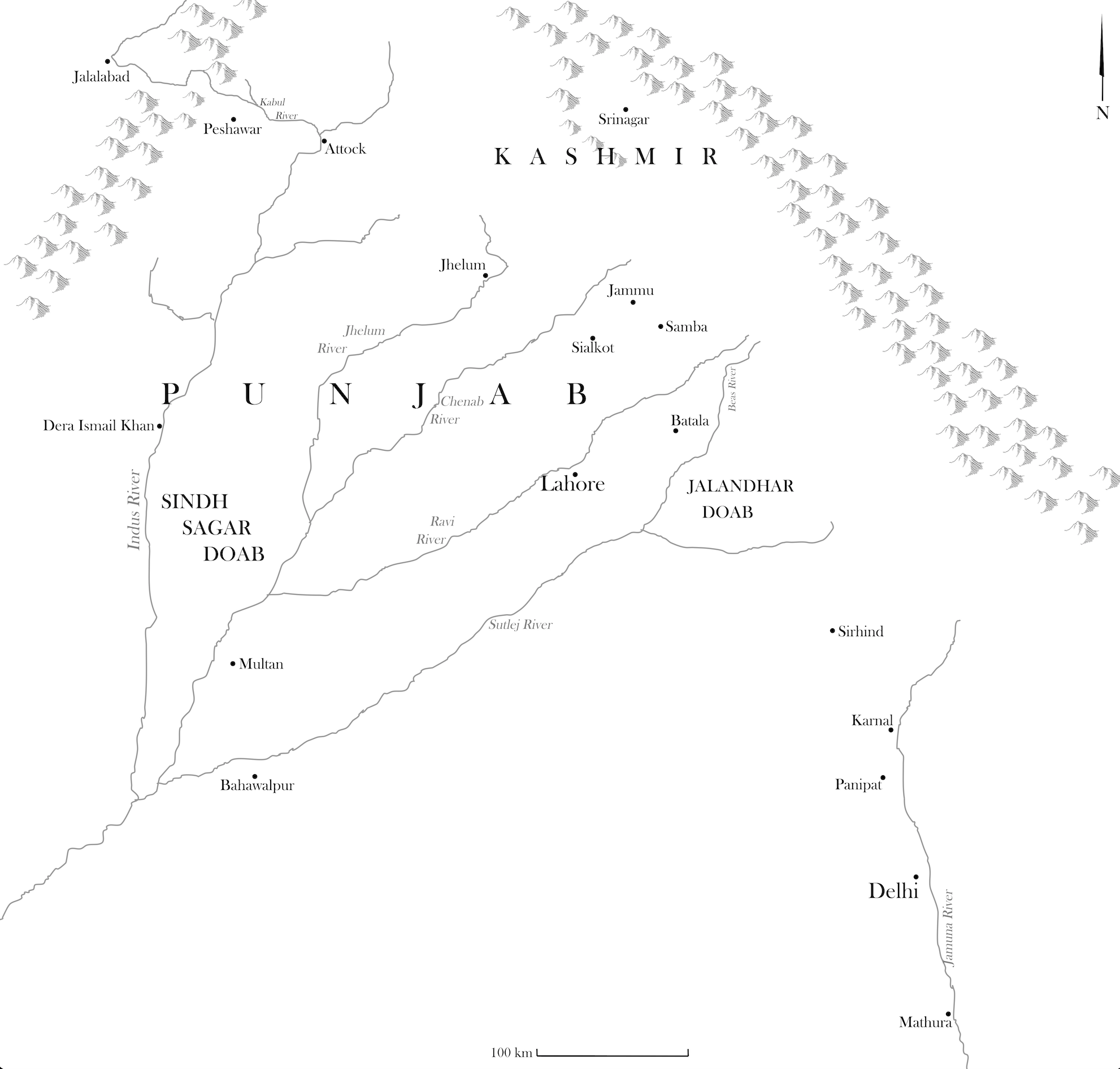

The Begum’s political career as told by Tahmas is a series of peaks and troughs, successes followed by setbacks. Punjab, a culturally diverse region whose plains are dominated by five great rivers, is today divided between eastern Pakistan and north-western India. In the mid-18th century, this was a violently contested land, divided between several powers. At the time, a weakening Mughal Empire was hemmed in by the ambitions of the Maratha Confederacy and the Durrani dynasty. Moreover, armed Sikh communities contested imperial rule and carved out their own domains. Mughlani Begum began her career by skillfully stepping in as regent for her infant son Amin Khan after her husband’s death. An ambitious political operator, she made sure to pay the court’s soldiers immediately after his death to ensure loyalty and would give commands on his behalf from behind a curtain at court in Lahore. Even when Amin Khan died as an infant and her son-in-law became nawāb, the Begum maintained control.

Over the next eight years, she found herself undermined and defeated by different officers, vassals, and allies. After each setback she tenaciously leveraged contacts to wrest back control, but struggled to find any stability. As was usual for the period, she made effective use of violence: she had at least one traitorous officer executed. Distracting from the fundamental political expediency of this killing with scintillating embellishments, some sources describe her maidservants beating him, sometimes wrapped in a carpet, before the Begum stabbed him to death. Tahmas, though, offers no such details.

Two of her primary allies were Ahmad Shah, and her daughter’s betrothed, Imad ul-Mulk, who was wazīr (chief minister) and de facto ruler of the Mughal Empire. Imad ul-Mulk, however, apparently disapproved of a woman ruling and tried to remove her from Lahore. Ahmad Shah was perhaps her closest ally: it was he who elevated her and made her ruler over the Jalandhar Doab, Jammu and Kashmir. By calling her his son, he ostensibly offered her some legitimacy in the form of honorary masculinity, a gender ambiguity she would further embody by wearing “male attire, with a turban and a cloak” on at least one occasion.

Ultimately, Ahmad Shah was more invested in his blood son Timur Shah, whom he made governor of Punjab, in an erasure of the Begum’s claims. Ahmad Shah encouraged her to take a pension and give up her lands, a forfeit she found beneath her dignity. Later, in 1760, he gave her Sialkot in Punjab as jāgīr (a kind of fief). Despite setting about the usual procedure and appointing officers to manage the province, she failed to rule her new domain: Sialkot’s landlords were recalcitrant.

The next year, Tahmas fled her service, rendering her effectively invisible until around 1779, when the two met agan at Delhi. Despite their bad blood, he claims to have helped the now-ailing Begum with her needs; she died two months later at Jammu.

Enslaver and enslaved, mother and son

As their ostensibly good-natured final reunion suggests, Tahmas Khan’s relationship with his enslaver was complicated – for a modern reader, even bewildering. The relationship was laden with complex dynamics of power, freedom, slavery, and family.

On the one hand, Tahmas’ position as the story’s writer affords him a certain narrative power relative to the Begum. Tahmas, despite his penname ‘Miskīn’ (humble, lowly) relentlessly ascribes good decisions to his own prudence, whereas bad outcomes he ascribes to the failure of others, including Mughlani Begum, to heed his advice. The narrative cycles between her rises and falls in an almost predictable manner, as he depicts her overstepping the bounds of ‘proper’ conduct.

Often the alleged failings of the Begum or her representatives are explained with reference to what Tahmas considers female inadequacies. When complaining of the apparent incompetence of the Begum’s khwāja sarās (often translated as ‘eunuchs’), he offers this verse: “The nawāb departed and one has to deal with women; what can women know of the worth of men?” On one occasion c. 1758 she offered to stand security for a debtor in Lahore, which Tahmas decries as “sheer folly.” He pointedly reminds his readers that “women are deficient in intelligence and do not possess the virtue of stability.”

Navigating the biases of such sources, and taking care not to reproduce them, is a necessary and difficult task. It’s important to read through the sexist language to understand the Begum’s own goals and aims. In this case, it appears that contrary to Tahmas’ claims, the Begum was in fact cannily trying to accrue political favors: the debtor was an agent of Adina Beg Khan, a powerful regional lord who would seize Lahore soon after. But by tying these invectives to womanhood, Tahmas positions himself in opposition to the Begum’s “folly” and ‘instability,’ not just as a capable servant but as a man.

Tahmas is also critical of her purported romantic affairs, and credits his own counsel with keeping her behavior ‘respectable.’ Soon before Tahmas fled, she struck up a relationship with one Shahbaz, whom she married in 1761. Tahmas was distraught at this marriage to someone below her social station, or, through another lens, her freedom to marry a man of her own choice. However, this was hardly the only reason Tahmas had to flee. She had, according to him, a record of imprisoning, mistreating and threatening to kill him.

This grim record reflects the fact that Tahmas’ historiographical power as a writer followed a life of disempowerment. Tahmas had been moved from one enslaver to another since early childhood, until he arrived at the court of Moin ul-Mulk. After the latter’s death, the Begum held great power over him. At one point she forced him into a marriage against his will. In a parallel to the moralizing criticisms he would later turn on her in writing, she chided him for debauched behavior and demanded he settle down.

While Tahmas obtained a noble title, khan, and was manumitted by the Begum, his social position was always below the established nobility. Despite his apparently capable handling of a governor’s position in Sialkot, Mughlani Begum removed him, reinstating the noble family that had governed before her takeover.

Lower social status was dangerous. Tahmas mentions a few occasions on which the Begum severely beat her maidservants for displeasing or failing her, even going so far as to kill one. In a telling episode around 1756, he was accused of having an affair with Mughlani Begum. For her, this accusation caused scandal, but for Tahmas, his very life was threatened by Imad ul-Mulk, who swore to kill him. Freedom and rank insulated the Begum from visceral threats to personal safety, and, in turn, allowed her to inflict violence on others.

Despite these deep tensions, Tahmas also seemed to feel strong filial loyalty for her, and even considered her to be like a mother. Part of this likely stemmed from his loyalty to Moin ul-Mulk. He may also have emphasized his steadfastness out of self-aggrandizement. Nevertheless, he did apparently continue to serve her, and refused to conspire with others against her, even during the lowest ebbs of her fortune or when she badly abused him. Despite his many criticisms, he credits the Begum as a “woman of wisdom and understanding.”

The story of Mughlani Begum and Tahmas’ complex relationship confronts the reader with questions about the role of gender and power in early modern India. How could the brutality of ownership and enslavement coexist and mingle with the bonds of mother and son? What control could disempowered people take by writing their own histories, and those of the more powerful? On the other hand, how many women of this era had an immediate voice in the historical record?

Modern depictions of a woman in power

Mughlani Begum’s lack of voice comes through in later representations of her which are often critical. While Tahmas Khan was no stranger to misogynist invectives, later sources either miss her humanity entirely or take the invectives further. In the Afghan court history Sirāj al-tawārīkh (c. 1912), the author Fayz Muhammad Katib not only mentions how “disgusted” male courtiers were with her behavior, but calls her “heartsick and frightened” at the prospect of Ahmad Shah’s 1756-57 invasion. The Ṭahmās-nāma, in contrast, offers an entirely different image of her confident ride into the Durrani camp at the head of her troops.

Perhaps a more significant example is Indian historian Jadunath Sarkar’s (1870-1958) well-known and well-cited series of books on the fall of the Mughal Empire. Sarkar was deeply appreciative of the Ṭahmās-nāma’s value as a primary source, viewing Tahmas as a highly credible eyewitness. However, he skirted around the realities of Tahmas’ position as an enslaved man, referring to him instead as a “page.” Thus his account of Mughlani Begum uncritically magnifies Tahmas’ emphasis on her capriciousness, brutality and pride. As Indrani Chatterjee argues, “the subtle revenge that the freedman-author extracted through remembering […] the ignominy and humiliation of the erstwhile mistress, was written out of Sarkar’s history.” Sarkar also adds details of the Begum’s apparent immorality which are missing from the Ṭahmās-nāma. Of note is the assertion that she singled out Delhi nobles to be plundered by the Durrani army in 1760.

There is great potential for deeper research on Mughlani Begum. This piece, largely reliant on translations, is in no way an authoritative analysis, but merely an encouragement of further investigation. More work must be done on the original manuscript of Ṭahmās-nāma, in the vein of Neelam Khoja’s recent article, as well as other 18th-century sources, specifically engaging with the Begum’s role. As the study of South Asia devotes itself further to untold histories, Mughlani Begum’s story offers a chance to explore the lives of late Mughal noblewomen in all their complexity.

References

Chatterjee, Indrani. “A slave’s quest for selfhood in eighteenth-century Hindustan.” The Indian Economic and Social History Review vol. 37, no. 1 (2000): 53-86.

Katib, Fayz Muhammad. The History of Afghanistan: Fayz Muhammad Katib Hazarah’s Siraj Al-Tawarikh Translated by R.D. McChesney and Mohammad Mehdi Khorrami. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Khan, Tahmas. Tahmas Nama: The Autobiography of a Slave. Translated and edited by P. Setu Madhava Rao. Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1967.

Khoja, Neelam. “Historical Mistranslations: Identity, Slavery, and Genre in Eighteenth-Century India.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 31 (2021): 283-301.

A Short History of the Origin and Rise of the Sikhs: An English Translation with an Introduction and Notes of the Hakikat-i Binā wa ‘Uruj-i Firkah-i Sikhān. Edited and translated by Indhubhusan Banerjee. Calcutta: A. Mukherjee & Bros., n.d. Original manuscript dated c. 1783.

Sarkar, Jadunath. Fall of the Mughal Empire, Vol. II, 1754-1771. First Edition. Calcutta: M.C. Sarkar & Sons Ld., 1934.