Mahsa Hojjati is an independent scholar of movement forms practiced throughout Iran. She is chair of the Iranian Dance Studies Working Group at the Dance Studies Association and her articles have appeared in Dance International Magazine. Follow her @mahsahojjati_mx

Eight years ago on a trip to my native Shiraz, I joined a tour that promised entrance to a space where pahlevan (champions) are made. Except as tourists, women do not usually enter the traditional training grounds for pahlevan, which are called zurkhaneh or the “house of power.”

As I stepped into the 200 year-old Zurkhaneh-ye Poulad in Shiraz, I marveled at the photos of past pahlevan lining the walls. Meel (Persian clubs) of varying weights were neatly ordered against one wall, and different sized kabadeh (bow-shaped chains of weights) rested under an arched nook. The intricately etched words Ya Ali Madad shone from the surface of a pair of meel, summoning Imam Ali, whose virtue and prowess in ancient battles are particularly revered and central to pahlevani culture.

A morshed sang inspirational verses and played zarb percussion, guiding the athletes in their timing and spirit. Besides meel and kabadeh, other zurkhaneh instruments for building strength include sang (shield-shaped wooden weights lifted while prone) and takhte sheno (a wooden slab for doing varied push-ups). Calisthenic and aerobic exercises cultivate coordination and balance through complex footwork combinations called raqs-e pa (dance of the feet) and pivot jump-spins called charkh. But the path towards becoming a pahlevan goes beyond training in physical strength; humility, fairness, and honesty are a few of many ethical qualities that are the foundation for pahlevani life.

Contrary to popular belief, many women throughout Iran are currently active in zurkhaneh sports. They find ways to train in private spaces but do not have the access to arena where they can be trained in the entire spectrum of practices by pishkesvat (veterans). After a short-lived period of support, in 2020 Iran’s National Pahlevani Federation banned women’s entry to goud arenas. In this article, I explore the paths of four women athletes I interviewed in 2022 who give new vigor to the meaning of Pahlevan.

Current pahlevani practices follow techniques put into writing seven hundred years ago by the 14th-century pahlevan and poet, Mahmoud Khwarazmi, known as Pourya-ye Vali. Some scholars point to zurkhaneh’s historic connection to Sufism and draw similarities between charkh and Sufi whirling. Others describe a past of javanmardi chivalry and Ayeen-e Mehr o Mitra rituals rooted in Mithraism. Whatever the origin of zurkhaneh, there is no doubt that pahlevan have been defined not only by their strength, but also by their kindness, generosity and dedication to helping the weak.

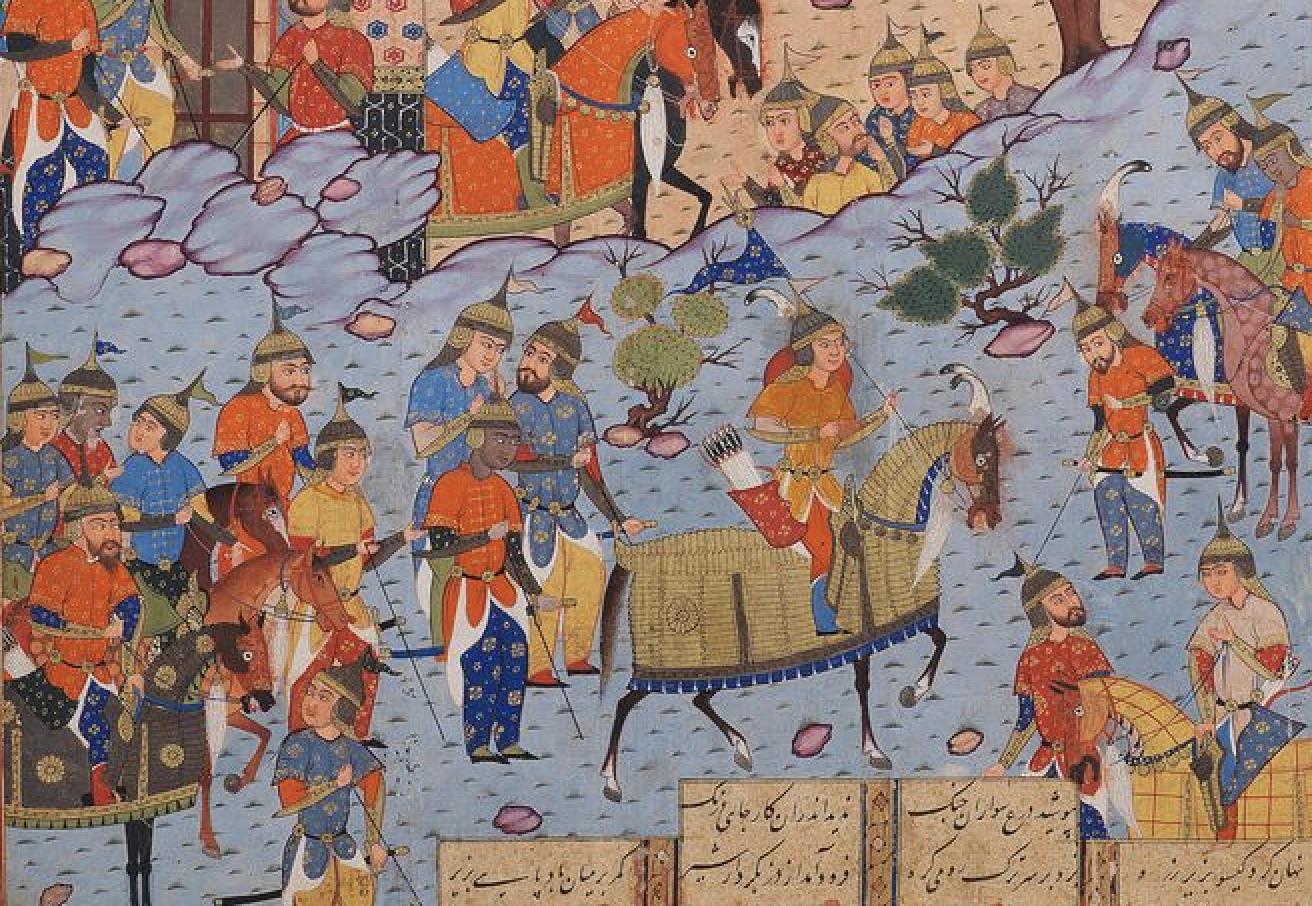

Ancient Persian literature such as Ferdowsi’s epic Shahnameh remind us that women exemplified pahlevani traits as well, whether as warriors like Gordafarid or through perseverance and loyalty like Manizheh and Shirin. Homay, who was a just and merciful ruler during her thirty years of political dominion, was yet another example of a powerful woman in the Shahnameh.

Around the world, women athletes’ access to sport has been wrought with struggle. Women’s participation in Olympic sports was only permitted long after men began competing. In Iran, women participate in many sports despite restrictions. Although there are no laws against women entering zurkhaneh, they are denied formal training, even though zurkhaneh rituals have been inscribed in UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage and the UN declaration of human rights upholds equal rights for men and women. Many practitioners believe formal training opportunities and spaces for women athletes could grant zurkhaneh sports access to international and Olympic levels.

Hard-working and perseverant, female pahlevan in Iran challenge stereotypes and limitations on women’s access to zurkhaneh. In showing us that physical strength and balance, humility and honesty are not just the realm of men, they reveal not only their capacity to cultivate strength, but also make evident Iranian women’s right to claim their historic and cultural patrimony.

Rayehe Mozafarian

A sociologist, filmmaker, and practitioner of zurkhaneh sports, Rayehe Mozafarian initiated the Zan va Zoorkhane page over two years ago, bringing visibility to women and girls who ingeniously find alternatives to goud arenas by practicing in their homes, women-only gyms or outdoors.

In April 2022, I interviewed Mozafarian in her home. She reflected on the seed that was sown the first time she heard the Director of the Board of Zurkhaneh Sports of Fars Province say women couldn’t practice zurkhaneh sports. Little by little, her admiration grew for zurkhaneh. “It brought with it a sense of love for my country,” she said, “only love for one’s country would move one to care for such treasures.”

Images she shares on Zan va Zoorkhane, such as historic pahlevani clothing for women on display in the Pahlevan Rostam Shah Lafata Museum near Mashhad, show that in the past, it was not unheard of for women to practice zurkhaneh sports.

Zan va Zoorkhane introduces us to women practitioners of all ages who love and respect this sport throughout the country, including girls who have learned the discipline from fathers and grandfathers who carve out spaces in which to teach them. From demonstrations of young girls able in charkh pivot-spins and takhte sheno push-ups, to youth and adult women practicing meel, kabadeh and sang, they show not only their coordination, balance and strength, but also the pahlevani attributes of respect, humility, and perseverance.

The page opens our eyes to young women training in zarb percussion unique to morshed, and young girls active in the art of naqali (theatrical recitations of Shahnameh stories). Ferdowsi’s magical couplets that weave together history and legend, extol the virtues of both men and women Pahlevan:

زنی بود برسان گردی سوار / همیشه به جنگ اندرون نامدار

… کجا نام او بود گردآفرید

… نهان کرد گیسو به زیر زره

به سهراب بر تیر باران گرفت / چپ و راست جنگ سواران گرفت

These excerpts are from a story describing the valiant warrior Gordafarid, who hid her long tresses under her armor, and rained arrows upon Sohrab while leading her horse left and right in battle. Later on in the story, when she splits his lance in two and Sohrab’s counterattack releases her helmet and reveals her long hair and thus her secret, he is filled with awe and admiration.

Mozafarian’s husband, Hadi Ahmadi, is a lawyer who has supported her work by obtaining numerous fatwa, Islamic legal rulings, in the past ten years by marja (religious authorities). Some fatwa state that “this sport is no different from other sports” in which women in Iran legally participate, and others note “there is no obstacle to practicing this sport if women abide by Sharia law.” The fatwa also refer to article 37 of the Iranian constitution which mentions “asl bar bara’at ast,” basically meaning that an act is not wrong until proven so in a court of law. Despite this, there are blurred boundaries of legal interpretation in Iran and people in positions of institutional power have taken independent action to block access, even without legal backing.

One of the most frequently repeated statements against women’s participation in zurkhaneh is that the goud is sacred and women’s entrance would tarnish it. Mozafarian’s response is that “women are allowed into sacred mosques for prayer, and a goud cannot be more sacred than a mosque.”

Mozafarian recalled that a hundred years ago in Iran, many people thought if women learned to write, it would lead to moral decay. “However, some women broke this barrier and held private classes that evolved into a school. When opponents burned down girls’ schools, promoters forged ahead and rebuilt them.”

“In the same way,” she says, “we need to build new zurkhaneh, on the ‘ashes’ of these zurkhaneh, until women claim this part of their national and cultural identity and men also say it is meaningless if women cannot participate.” Mozafarian’s film, Lab-e Goud makes women’s ability crystal clear. Zan va Zoorkhane introduced me to the world of women practitioners including the three women below who I interviewed next.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vSuhh74ndC4

Shanaz Fadaii

The Zagros mountain range in southwest Iran holds the reputation of being the historic terrain of courageous people, including Bakhtiari, Lori, Qashqai, and Kurdish communities, among others. Shanaz Fadaii is a Bakhtiari woman and native of the region who has been involved in sports all her life, most recently as a handball coach. During our interview in September 2022, Fadai related her first experience with zurkhaneh sports in front of a large crowd of spectators during the 4th annual Women’s Islamic Games in Tehran’s Azadi Stadium in 2005.

A morshed suddenly called out to the spectators: “Who can swing kabadeh? Ya Ali, here is the goud and here is the arena!” Several men entered the arena and tried, many unable to lift the kabadeh over their heads. Fadaii, who was participating as a juror, rose and approached the morshed. He claimed she was not strong enough, but the crowd insisted the morshed let her try.

Fadaii entered the arena and swung the kabadeh over her head: back and forth 26 times – although she had no prior training in any zurkhaneh sports. The surprised morshed gifted her a badge and a book and subsequent interviews followed. “I was proud to show that women have many abilities and can be active in spaces from which they are excluded. I am just one example of women, like wrestlers and weightlifters, who are strong and able,” she told me. She believes that if women had the permission and support nationally, they could train and succeed at the sport at an international level.

Following the event, Fadaii went repeatedly to the Board of Zurkhaneh Sports of both Fars and Kohgiluyeh provinces to request a permit and space where women could be trained, but she was repeatedly rebuffed. Despite her strength and talent, she didn’t continue with zurkhaneh sports. Her hope is “to witness the day that women will have access and support to train in any sport they have the talent and interest for, including zurkhaneh.”

Fatemeh Esbati

In a series of long-distance conversations in early September, Fatemeh Esbati shared her memories with me. As a child, she loved to watch zurkhaneh sports that were broadcast on television. The sounds of zarb and poetry connected her with the love she had for the maddahi songs of prayer that she had been raised with in Ardabil.

She had always wanted to train with meel, and finally taught herself through watching videos. When a neighborhood zurkhaneh allowed her to train in the goud during empty hours, she realized she had found what she had always wanted. She has been training solo in zurkhaneh sports for the past ten years and now regularly works out with a pair of 26 kilogram meel.

In the brief period of the Zurkhaneh Federation’s support of women practitioners, Esbati won first place in the women’s heavy meel division and received a certificate and the title of Qahraman (champion) in October 2020. This is when many of Esbati’s followers and fellow Iranian Azerbaijanis started referring to her as “Iran’s first zurkhaneh woman.” The certificate was signed by a kohneh-savar (well-known and experienced) pahlevan who was also the founder and supervisor of a girl’s youth team in Kerman (that subsequently halted activities after facing opposition).

When a past video of Esbati’s kabadeh swinging sparked negative comments, the Federation barred women from entry into zurkhaneh. Besides practicing meel, sang and kabadeh, Esbati has also been active in other sports such as powerlifting for which she won a gold medal in September 2022 in Tehran.

In response to men who belittle women’s strength, she says, “mothers carry a heavy weight inside them for nine months, so it’s evident that women naturally have much strength in their bodies. As a practitioner of both weightlifting and zurkhaneh sports for the past ten years, I know that training with heavy weights in the right manner is not harmful to the body. These exercises not only build stronger, leaner muscles, but also increase bone density.”

Pahlevani philosophies maintain a special respect for mothers who raise zurkhaneh athletes, strong in body and pure in thoughts and actions. As Esbati says, “mothers are the ones who teach their children humility, dignity and respect for elders.” Esbati has not only given steadfast support to her athlete daughter and son, but is a true pahlevan herself.

Farnoush Djavaheripour

Women active in zurkhaneh sports can even be found outside of Iran. Farnoush Djavaheripour left Iran seventeen years ago and moved to Canada, where she has been an aerobics instructor for the past ten years. During my Zoom interview with her last August, she reminisced about the start of her attraction to zurkhaneh sports. When searching for music and movements she could use in her classes (a zumbaesque style of aerobics fused with Middle Eastern movements), she began to view zurkhaneh footage online.

Her appreciation and admiration for zurkhaneh sports grew the more she researched, watched videos, and practiced on her own. The connection she felt with zurkhaneh was so strong that she thought, “God, this is my thing, this is what I have been searching for. I felt like a child who had been raised in an orphanage that suddenly met her parents.” Excitedly, she said, “this rhythm, this zarb (percussion) was what was in my blood.”

“Zurkhaneh is not just a sport, it’s a whole system of interrelated practices including the spiritual aspect.” Djavaheripour explains how she was able to reach her level of ability in only two years: “I realized zurkhaneh consisted of a collection of elements that I already held within,” including literature, poetry, traditional music (which she had studied by playing setar), singing, the spiritual aspect, and the collective aspect.

She is particularly drawn to the rhythmic movement, raqs-e pa, but also enjoys the strength-building exercises using organic natural tools. Generally, she is interested in traditions and believes the martial aspect also comes naturally, since her father was in the army and raised them military-style. In a way, all the elements necessary to zurkhaneh sports were already part of her life.

Today, Djavaheripour continues training not only in meel, kabadeh, sang, and takhte sheno, but also in charkh and aerobic raqs-e pa sequences. Ever pushing herself in new directions, she also explores shirinkari with meel: the practice of churning the meel in infinite patterns and meelbazi where the meel are alternately caught and sent spinning into the air. The creative paths possible in zurkhaneh especially appeal to her, so she continues to sing and write poetry. Pahlevan and a mother too, her creative cultivation of strength and beauty is an inspiration for others.

As a wise morshed once sang,

پهلوان بودن فقط در زور نیست

زور بازو که فقط منظور نیست

پهلوان بودن فقط در مرد نیست

Being a Pahlevan lies not only in strength

The point is not only physical strength

Being a Pahlevan is not only of men

References and Further Reading

Ajdarikhah, Seyed Fakhradin. 2018. Do Mirās-e Javedān: Zurkhāneh va Namāyesh-e Pahlevāni.

Dabashi, Hamid. 2019. The Shahnameh: The Persian Epic as World Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 60.

Rahmanian Elaheh and Reza Ashrafzadeh. 2020. “Women in Shahnameh: An Overview on Mythical, Lyrical and Social Aspects.” In Revista Humanidades 10 (1). https://doi.org/10.15517/h.v10i1.39816

Rochard, Philippe, and Denis Jallat. 2018. “Zurkhaneh, Sufism, Fotovvat /Javanmardi and Modernity: Considerations about Historical Interpretations of a Traditional Athletic Institution.” In Javanmardi: The Ethics and Practice of Persianate Perfection, edited by Lloyd Ridgeon. London: Gingko, 232–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv75d0fs.12.