The follow is an interview with Parham Ghalamdar conducted by Walker Downey.

Parham Ghalamdar is an Iranian painter with a background in graffiti based in Manchester. He studied MA Painting at Manchester School of Art and specialized in oil painting. Follow his work and Instagram.

Walker Downey is a historian of modern and contemporary art. While anchored in art history, Walker’s research cuts across media studies, musicology, and sound studies. His primary focus is the contemporary field of sound art and its historical and technological roots.

In May 2022, Iran-born and Manchester-based artist Parham Ghalamdar contacted London record label and radio show Death is Not The End with an unconventional proposal for a release: he would cull audio excerpts from his family’s own home-videos, and transplant them to cassette tape, giving these sonic fragments a life apart from their associated footage. On its own, this act of audiovisual translation—tape-to-tape transfer—constitutes an intriguing premise for a work of experimental sound; but the precise nature of Ghalamdar’s footage ensured that his gesture would carry a more substantial emotional weight.

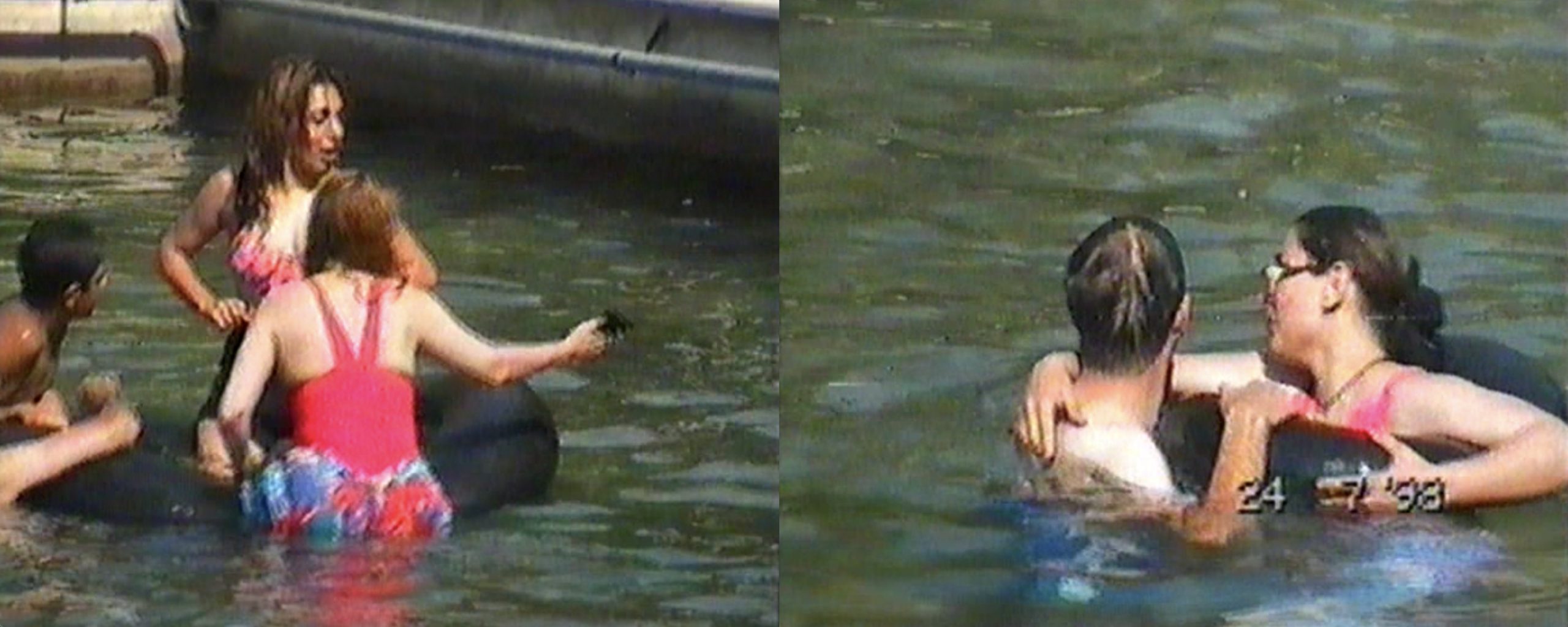

As a child growing up in Iran in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Ghalamdar had witnessed countless family gatherings—some held in private, and others in “the middle of nowhere in nature”—marked by exuberant group sing-alongs of Persian folk and pop music, uninhibited dancing, the recitation of poetry, and outpourings of laughter and dialogue. These moments of song, dance, and untempered joy, many of which played out in celebration of birthdays and holidays, were documented with a handheld camcorder by Ghalamdar’s mother—committed, for posterity, to the tightly coiled reels of VHS tapes.

At the height of the pandemic, during which time he was living and working in England, Ghalamdar rediscovered these tapes and was struck by a feeling of historical distance; no longer feeling “personal” ownership over them, he saw reflected in their footage a more universal set of experiences—pleasures, pains, and memories common to middle-class Iranians living through a tumultuous millennial transition.

As Ghalamdar has explained, Beautiful Apparitions was always intended as a document of ecstatic political resistance, for in Iran, throughout the 1980s, and much of the 90s, the mere ownership of personal video equipment—camcorders, tapes, and players—was prohibited under a nationwide ban. The ban on video equipment, which aimed to slow the circulation of foreign movies and limit the sort of home-grown moviemaking threatening to the state’s media apparatus, was instated in 1983 by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (MCIG). The ban was lifted only in the mid-90s. Ghalamdar thus sees the sounds of song, dance, and laughter collected on Beautiful Apparitions as “illicit” documents of lives lived in joyous opposition to state control, as well as reminders that Iranian culture has never been crudely synonymous with what the MCIG and the country’s “morality police” see fit to sanction.

But trauma and unrest unleashed in Iran between the initial production of Beautiful Apparitions and its October 2022 release have added considerably to the tape’s emotional and political weight: following the September 16, 2022 death of Mahsa Amini, a Kurdish-Iranian woman detained by morality police for wearing an “improper” hijab, and beaten and killed while in custody, the nation erupted in protests. To date, thousands of protestors have been arrested, and hundreds have been reported killed. And yet, Iranian women have continued to take to the streets, armed with chants and flaming hijabs; meanwhile, protest art has erupted through a variety of channels, taking shape as Instagram posts and ephemeral outdoor interventions.

In the following interview, conducted over e-mail and Zoom, I ask Ghalamdar to speak about the origins of the Beautiful Apparitions project, its meaning in the broader context of his “primary” practice as a painter or his former graffiti practice, and its new (or renewed) political resonance in the face of Iran’s ongoing protests. Ghalamdar also hints at further plans for the sounds of Beautiful Apparitions and their VHS source material, indicating that his cassette release is “just the beginning.”

I’ll begin with a basic question: what exactly are we hearing when we listen to Beautiful Apparitions?

We are listening to young Iranians in their mid-thirties singing, dancing and drinking, events which are happening in private spaces or in the middle of nowhere in nature. These sounds are amateur performances of Persian folk, pop songs, and poetry recitation mixed with chaotic moments of laughter, banter and gossiping. They are singing romantic songs about love and loss in celebration of life.

This was happening when dancing and singing with such pop songs was illegal and owning such footage was extremely risky. Also, VHS tapes were illegal until the mid-90s. Previous generations have memories of smuggling Madonna and Michael Jackson cassettes and posters to Iran. My step-dad has a lot of memories of duplicating such cassettes by soundproofing and isolating a set of tape recorder and tape player in an empty, unplugged fridge back in the 1980s and 1990s.

I’d love it if you could briefly narrate the genesis of this project. What was your relationship to the VHS footage that we hear (re-)captured on the cassette? When did you first encounter it, and when did you first decide to integrate it into a project? Meanwhile, what inspired you—a visual artist and a painter—to translate this footage into a purely sonic document?

I was very conscious that my mom had been recording special occasions like birthdays and holidays since I was a child. I rediscovered these VHS tapes when the COVID lockdown happened in 2020. At that time, I was reviewing the footage in a whole new context. I was watching the tapes under the shadow of my immigration/refugee experience. I realized that this was not personal footage anymore after twenty years; I spotted a historical quality in it. The tapes have transcended beyond my personal footage because a lot of other middle-class Iranian families have the exact same memories and experiences of oppression and secretive double lives. I felt an immediacy, an urge, a priority that I had to attend to.

The pursuit of truth made me, a painter, do this; I’m surprised no one did it before me. To me these tapes prove that the government doesn’t fit the culture of Iran and all Iranians. The tapes prove the love of Iranians for celebrating and living a life worth living. Also living as a refugee in England, I have experienced a lot of racist incidents where stereotypes of radical Islamism are projected onto me. In one occasion I was stopped at the Leeds Bradford Airport and I was asked if I had been “in touch with signs of radicalisation.” I wanted to challenge the stereotypical Fox News-like depiction of Iranians and Middle Easterners. There is an exhausting, unspoken demand from me and people like me to prove that we are cultured, sociable, and intelligent human beings. We saw good examples of it with the racist coverage of the Ukraine war.

I grew up with cassette tapes of Persian folk stories, nighttime stories, lullabies, and soundtracks. I was a member of the Iranian Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults and I used to receive a lot of books and cassettes produced for children. Cassette tapes were allowed despite the fact that VHS tapes and players were for a long time illegal. I watched a lot of films in VHS format, particularly the American Western Spaghetti films such as Nevada Smith (1966). So, cassettes and VHS tapes were a big part of my childhood and my life.

Beautiful Apparitions arrives during a time of great trauma and turbulence in Iran: the tape was released less than a month after Mahsa Amini’s death at the hands of morality police launched demonstrations around the country. But as you began this project in Spring 2022, clearly, this alignment could not have been foreseen. How have recent events changed your own understanding of the tape’s meaning and purpose? What do you hope Iranians at home and abroad will hear in this cassette at this moment?

I wrote an email to Death Is Not The End at 3 AM on May 5, 2022, way before the current brewing revolution. The past few months have changed my entire viewpoint toward life. I have fallen in love with my people and birthplace again. I have cried and laughed with VHS tapes and the news coming out of Iran every day – I even grew white hair on the left side of my head.

The tapes and the revolution overlap a lot: they both are about taking back our lives, bodies and embodiments. Those secretive gatherings have definitely contributed to current events. The Generation Z that was raised in such hidden gatherings is now leading the revolution, which was completely unexpected for a lot of people. I think the tapes could shed more light on the recent events; we can see some of the cultural reasons why there is a revolution now. The tapes and the recent uprising acknowledge and justify each other.

There’s a startling rawness and directness to the sounds of Beautiful Apparitions. There is no sense that the songs, conversation, poetry, and laughter contained on the tape have been massaged or manipulated—everything seems to unfold at its own pace, proudly bearing the technological grain (that flickering buzz) of the VHS source tapes. What motivated the “hands-off” approach you seem to have taken here?

Honesty was the main ingredient. Any manipulation would have killed the innocent pure quality of honesty in this historical documentation. There is no fiction or personal truth here.

I have been subjected to authoritarian mega narratives all my life. As an artist and art student I have been studying propaganda all my life. I can differentiate propaganda/messages from a million miles away. Films like “Top Gun 2” and “Darkest Hour” physically disgust me. I think manipulation and messaging would have been an act of underestimating the intelligence of my audience here. I think anyone who loves life and living could relate to the basic act of dancing, singing, and laughing could easily relate to this tape.

I did get advice from my musician friends on how to deal with these tapes. My musician friends were all interested in using them as the raw materials to produce music, which I will probably do. However, I think the mission is something else here. I am only a curator here, curator as the most accurate etymological meaning of the word: I am only taking care of these archival sounds.

This past August, you exhibited additional tapes drawn from your parents’ home archives in a group show at the Manchester venue Soup Kitchen; here, the tapes were presented in the form of a multichannel video installation. Do you have any other plans for this footage?

I just recently produced a music video for the Mistys, a British electronic pop duo based in Manchester. The video, for the single “Strange Shadows,” is a montage of sequences depicting Iranian women in bikinis around a private pool during their holidays. All the materials are extracted from the VHS tapes. I am planning to have still-image exhibitions and books out of the tapes. This is just the beginning.