The following post was written by Marwan Kaabour, a London-based, Beirut-born multidisciplinary artist and designer in the art and cultural sector. He is the founder of Takweer, a platform that explores and archives queer narratives in Arab history and popular culture.

***

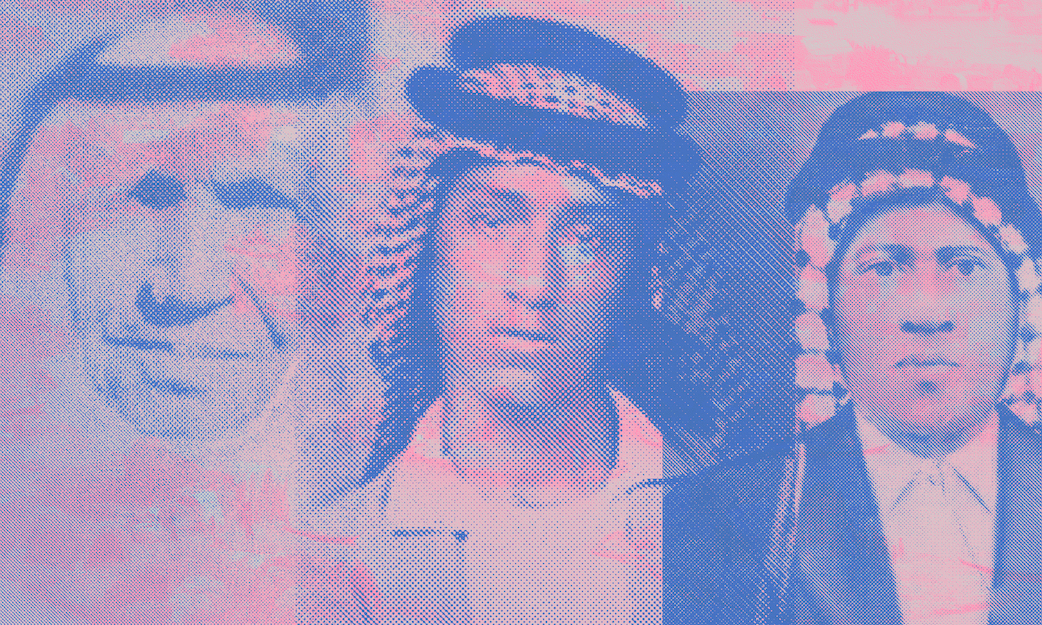

Masoud El Amaratly is an Iraqi singing legend. Born at the turn of the 20th century, in the lush marshes of southern Iraq, El Amaratly captured Iraqis’ hearts with his powerful renditions of Rifi folk songs that evoked a sense of lament, melancholy and longing.

His distinctly sorrowful, melodious and hoarse voice is ever present in modern Iraq, recalling the rugged natural landscapes of the marshes and tales of past lovers.

El Amaratly is not only one of Iraq’s most famous singers; he is also one of the Arab World’s most well-known transgender icons. Before Masoud was a singer, he was a shepherd with a great voice. Assigned female at birth, El Amaratly was born to parents who worked as servants at a tribal chief’s residence. As he got older, it was expected of him to follow suit. But an incident when he was eighteen years old set him on a different path.

While working as a shepherd at a town elder’s home, El Amaratly would start his day at dawn singing rural folk songs. One day while he was out in the fields, two men followed Masoud in an attempt to harass him. He stopped them, bound them, and led them to his employer’s home, where they confessed.

The town’s people praised his courage for stopping and standing up to the harassers. At that point, Masoud’s appearance was still feminine-presenting, but his job as a shepherd, as well as his actions which were perceived by his community as “strong” and “masculine,” created the perfect opportunity for him to begin expressing his gender identity on the exterior. From that moment onwards, he reportedly began donning traditional male dress (Shemagh and Agal). It was also around the same time that his singing began to gain praise too, and he was invited to perform at various occasions around town.

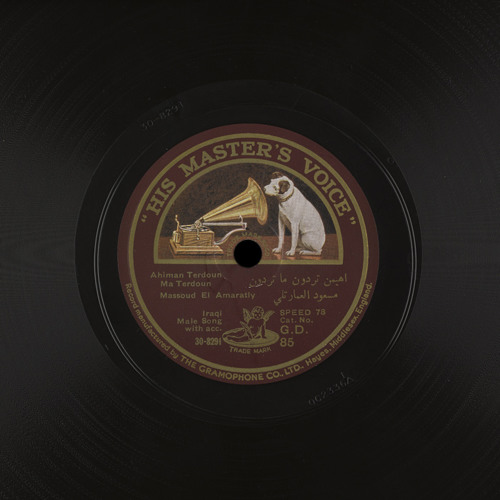

He later moved to Al-Amara, in south-eastern Iraq, where he would sing in cafes. It was then that he became known as Masoud El-Amaratly (“Masoud from Al-Amara”), and was later discovered by a music agent who took Masoud to Baghdad to make records between the mid-1920s and mid-1930s. His fame spread all over Iraq, Syria and Lebanon as a country singer with a melodic and distinctive voice. He was a pioneer of abuḏiya, a colloquial form of poetry and singing that was popular amongst the Ahwari community.

Ahwaris, also referred to as Marsh Arabs (and derogatorily as Maʻdān or Shroog), are a community that inhabit the Mesopotamian marshlands in modern-day south Iraq. The marshes lie on a vast floodplain where the end of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers come together to form an extensive inland delta.

The different tribes that call the marshes their home have developed a culture centered on the marshes’ natural resources, with houses constructed from reeds harvested from the marshes themselves. Their culture is unique and distinct from neighboring Arabs, as well as city and village dwellers.

Abuḏiya poetry and singing was born out of the Ahwari lifestyle, and it centered themes of longing, melancholy, and was used to explore sorrow and misfortune. It can be said that this style is an Iraqi Ahwari counterpart to Blues. El-Amaratly’s naturally hoarse voice, underpinned with a sad tinge, was a perfect vehicle for this genre.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D3HoYjou-jc

While today, Iraq is widely seen as a conservative society in terms of gender norms, El Amaratly’s life shows how recent this change was. He was part of the Mustarjil gender identity, a transgender community in southern Iraq which challenged the stereotypical binary understanding of gender.

Mustarjil is an Arabic term meaning “becoming [a] man.” Although it can be used derogatorily to refer to women who are perceived as having a masculine appearance and/or mannerisms, in Iraq’s marshes, it existed as a gender identity. Within the context of the Ahwari community, Mustarjil was a common gender identity, where people assigned female at birth decide to live as a man after puberty, and this decision was generally accepted in the community. The Mustarjils were one of many similar third gender categories around the world, such as the Hijras in South Asia.

We have a great wealth of written records that point to a long history of gender and sexual diversity in the Middle East. This includes, for example, literature around the mukhanathun (gender-variant people), the non-normative sexual practices of caliphs, or the wild sexual endeavors narrated in One Thousand and One Nights. These stories complicate the contemporary dominant binary understanding of gender and sexuality. Takweer, a virtual space I founded in 2019, explores, documents, and archives such narratives in Arab history and popular culture.

In texts from the mid-20th century, the Mustarjil are mentioned non-controversially as a part of Iraqi life. The Marsh Arabs is a travel book first published in 1964 that describes the eight years during the 1950s that Wilfred Thesiger (a British military officer, explorer, and writer) spent traveling in Iraq’s marshes. The book includes several accounts of gender fluidity amongst the Ahwari community. His account, although written in language that present-day readers might find problematic and based on his limited experience, is valuable because it sheds light on gender and sexuality norms in southern Iraqi society at the time.

“One afternoon, some days after leaving Dibin, we arrived at a village on the mainland. The sheikh was away looking at his cultivations, but we were shown to his mudhif by a boy wearing a head-rope and cloak, with a dagger at his waist. He looked about fifteen and his beautiful face was made even more striking by two long braids of hair on either side. ln the past all the Madan (Ahwari) wore their hair like that, as the Bedu still did. After the boy had made us coffee and withdrawn, Amara asked, ‘Did you realize that was a mustarjil?’ I had vaguely heard of them, but had not met one before.

‘A mustarjil is born a woman’. ‘She cannot help that; but she has the heart of a man, so she lives like a man.’

‘Do men accept her?’

‘Certainly. We eat with her and she may sit in the mudhif. When she dies, we fire off our rifles to honour her. We never do that for a woman. In Majid’s village there is one who fought bravely in the war against Haji Sulaiman.’

‘Do they always wear their hair plaited?’

‘Usually they shave it off like men.’

‘Do mustarjils ever marry?’

‘No, they sleep with women as we do.’”

Thesiger continues to narrate several other accounts of mustarjils within the same community, as well that of a “stout middle-aged woman” who wanted to remove her male organ in order to “turn into a proper woman.” Thesiger later mentions: “Afterwards I often noticed the same [person] washing dishes on the river bank with the women. Accepted by them, [she] seemed quite at home. These people were kinder to [her] than we would have been in our society.” Around that time, Britain was still living under the shadow of Victorian norms, and gender non-normative people were still stigmatized and shunned. Communities such as the Ahwaris, presented an alternative model that created space for communities like the mustarjils, despite the dominant gender binary.

Concepts of gender and sexuality around the world were historically more complex and multifaceted than the gender binary we have today. The expansion of European empires was accompanied by the introduction of legal codes, laws, and customs throughout its colonies that banned homosexuality, sodomy, and “unnatural” gender expressions. According to Enze Han and Joseph O’Mahoney, who wrote the book British Colonialism and the Criminalization of Homosexuality, British rulers introduced such laws because of a “Victorian, Christian puritanical concept of sex.” “They wanted to protect innocent British soldiers from the ‘exotic, mystical Orient’ – there was this very orientalised view of Asia and the Middle East that they were overly erotic. They thought if there were no regulations, the soldiers would be easily led astray.”

It would be simplistic to assume that prior to colonialism, gender variance and non-normative sexual practices were completely accepted in the region. But throughout history, we have records that show a relative degree of acceptance. The first recorded relationship between two women in Arab history was in the Encyclopaedia of Pleasure (Jawāmiʿ al-Ladhdhah), written in the 10th century by the medieval Arab writer Ali ibn Nasr al-Katib. It cites the princess Hind Bint al-Nu’man’s love for Hind Bint al Khuss al-Iyadiyyah, known as al-Zarqa’, as a romantic ideal.

Non-normative practices even extended to the region’s rulers. Abu Musa Muhammad ibn Harun al-Rashid, better known by his regnal name of al-Amin, was the sixth Abbasid Caliph. He was known to prefer the company of and was sexually involved with his ‘harem’ of eunuchs, also known as ‘ghulams.’

It is crucial that we recover, document, and archive the memory and history of this complex gender landscape in order to debunk popular myths that have been haunting the region since the turn of the 20th century. On one hand there are myths directed from the West, which claim that people from the SWANA region are innately sexist, homophobic and transphobic. These claims have been used to justify oppressive Western policies to “fix” these supposedly innate qualities that in turn cause more violence, such as the US invading Afghanistan and Iraq to “liberate women” or Israel’s cynical use of LGBT rights to “pinkwash” its oppression of Palestinians. The second myth, meanwhile, is homegrown; many in the Middle East claim that any deviation from binary gender norms is a Western import, and does not abide by the ‘principles and morals’ of our region.

But the long history of gender diversity and fluidity in the region shows both of these claims to be untrue. And the story of Masoud El Amaratly reveals that even into the present, forms of gender diversity have been accepted in much of the Middle East. The fact that one of Iraq’s most beloved contemporary singers is a transgender icon challenges both Western and local stereotypes about the region.

After serenading his adoring fans for years, Masoud El Amaratly later returned to his hometown and married a local domestic worker. He then got married again to a lady called Kamila.

The Arabic Wikipedia entry of Masoud El Amaratly uses his deadname, but then goes on to lay endless praise to his skill and music. The way his legacy is today discussed, vis-à-vis his gender identity, remains unresolved, perhaps a result of how rapidly norms around gender identity and transgenderism have changed in Iraqi society over the last century.

Iraq’s landscape has changed as well. In the 1990s, Saddam Hussein drained Iraq’s marshes as collective punishment against the region. Hundreds of thousands of Ahwaris were displaced in what amounted to ethnic cleansing, a process that also tore apart the wetlands’ unique culture. Despite efforts to revive them, climate change has made life in the marshes increasingly impossible.

Despite all the changes, Masoud El Amaratly remains one of the musical giants of Iraq’s history, loved and admired by Iraqis then and now. Even long after his death – and the destruction of Iraq’s fabled wetlands – Masoud El Amaratly’s melancholic voice will forever evoke Iraq’s marshes and its sonic landscape.