The following piece was written by Katayoun Vaziri, an Iranian visual artist based in Mexico City. Her creative work focuses on daily life and its relation to structures of power. Born in 1983 in Tehran, she received her BA from Tehran University and later studied in the US.

The accompanying images are primarily anonymously-taken photos that circulated on social media during the protests in Iran in Fall 2022.

***

Fountains turned blood red. Murals defaced. Performance art as a mechanism of remembrance and defiance. Tehran’s roofs transformed into a sonic battleground, from which protest chants ring out nightly as battles continue in the streets below.

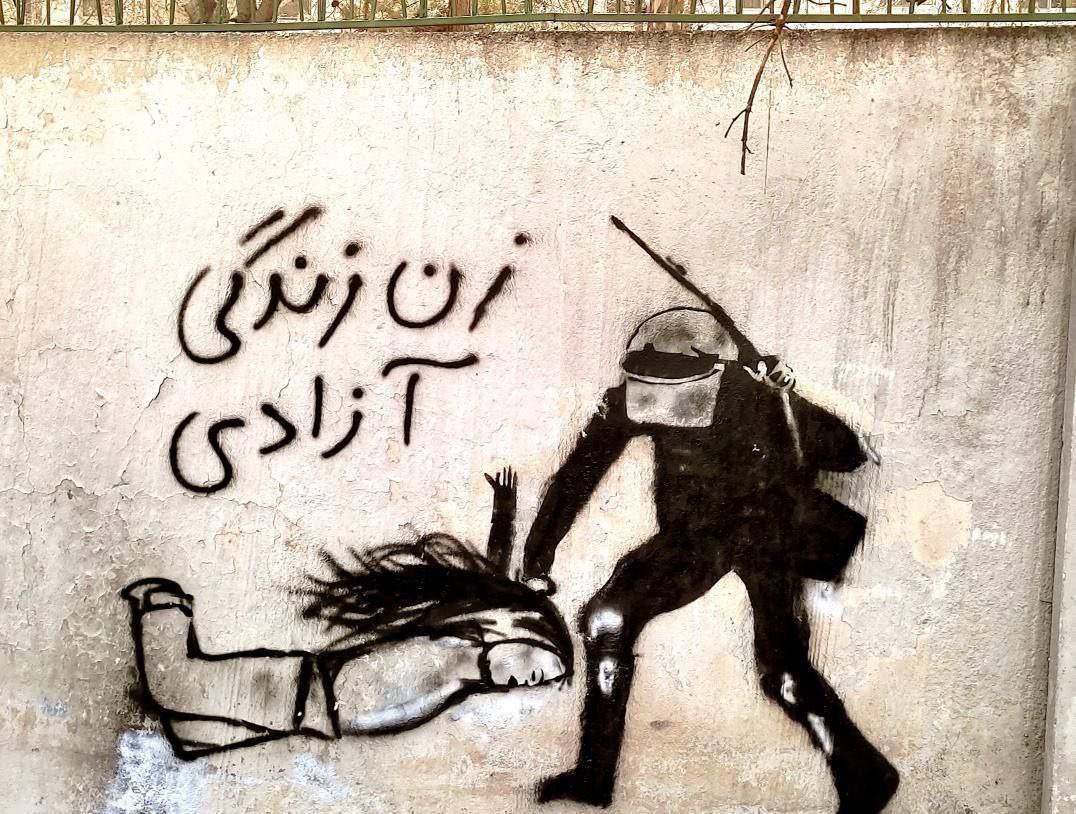

Starting in September 2022, Iran witnessed an uprising that saw protests across the country in reaction to the killing of Mahsa Zhina Amini by security forces. As thousands were arrested and killed in what became known as the Zan Zendegi Azadi (Woman Life Freedom) uprising, artists turned to the language of visual and performance art to make visible the violence of the state and the bravery of protestors. These artists, often in conversation with one another and building on similar imagery, subverted government ideology and created webs of solidarity across Iran and beyond its borders.

A horizontal, anonymized, and decentralized network of art-making emerged as a way of communicating between resisting members of Iranian society. Through this web, artists and protestors encouraged and continue to encourage each other to keep fighting. Recordings of these performances and visual art contributed to and magnified the protests inside Iran, and came to dominate how the Iranian diaspora and the world responded.

In this article, I examine the webs of art making that emerged during Iran’s Woman Life Freedom uprising and their accompanying political ramifications. I explore how Iranian artists and art collectives as well as art institutions responded to the uprising, specifically by subverting state symbols and ideology, performing resistance, circulating joy, and drawing on repetition as a form of critique. Lastly, I examine the politics of Iranian art in the diaspora, and how attempts to demonstrate solidarity with the uprising at times reproduced problematic power dynamics.

This piece is by no means an exhaustive analysis or catalog of art during the uprising; instead, it is meant as an archive of a particular visual language of resistance that artists created amid the protests.

Reclaiming Blood as a Symbol

Protest art in Iran has continually redefined and reappropriated visual elements that have been symbols of state power since the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Early in the protest movement, anonymous artists drew on a common motif in state-funded art – fountains of blood – and resignified its meaning for the public. Though the following images appear similar, they are very different in what they represent:

The above are both photographs of water fountains that have turned red, symbolizing the notion of martyrdom. The photographic image on the left depicts a public art installation created in 1985 as part of efforts by the government to highlight the martyrs of the 1979 revolution and the Iran-Iraq war. The fountain’s red water symbolizes their flowing blood and the images on the wall show what type of martyrs can be honored by state propaganda, i.e., only those who are government-approved. This excludes, for example, Marxists, women, Kurds, and other groups whose efforts were erased from the state-dominated narrative of revolution and war.

The photograph on the right, however, is of a fountain turned red by an anonymous artist during the protests. A few weeks into the uprising, in October 2022, pools and fountains in Park-e Daneshjoo (Students’ Park) in Tehran turned red. This time there were no images of Iranian leaders Khamenei or Khomeini by the fountain. Instead, the context was the street, and the narrators were anonymous actors.

Repeating this powerful element of past propaganda art in a new time and context, the meaning of the work changed. The same visual gesture of the fountain with red water was no longer about a state-enforced idea of martyrdom imposed on its people, but rather represented the sacrifice of everyday citizens fighting for their freedom.

Because of its powerful message, in other cities, like Shiraz, the gesture was soon repeated.

The anonymous nature of this act not only protects the artists, it also encourages a sense of collective ownership, both representing and coming from the people, as opposed to being funded and curated by the state.

This struggle to redefine elements of Iranian government semiotics also manifested in efforts to change government-funded wall paintings, slogans, and ads. Since the early 1980s, Tehran’s streets have been filled with government-sponsored imagery reflecting the state’s ideology, increasingly alongside advertisements.

During the uprising, there was an epic and at times humorous war between anonymous interventionists and government agents, each trying to reclaim public space. Protestors covered murals with red paint, symbolizing blood, and wrote slogans across city walls.

Authorities, in response, tried to repaint murals to erase the blood, and constantly covered up what they considered graffiti. But soon after, the same murals and walls would be covered again with protest art.

Collective Performance of Resistance

Chanting slogans on the rooftops as a collective performative act is another gesture that has gone through many iterations in Iran over the last 45 years. During the 1979 revolution against the Pahlavi monarchy, people would take to their rooftops at night and chant “Allaho Akbar,” meaning “God is Great,” to defy the regime’s curfew that was intended to stop protests.

During the Green Movement of 2009, the same gesture of chanting “Allaho Akbar” on rooftops was repeated, but this time it was meant as a slogan against the Islamic Republic, in solidarity with those protesting on the streets demanding a democratically-elected government. In both cases, saying “Allaho Akbar” signified that God was on the protesters’ side and was stronger than the state’s violence.

In 2022, the same gesture was repeated. But this time there was a change – a new slogan: “Woman, Life, Freedom.” At other times, people shouted “Death to the Dictator.”

These repetitions and transformations make clear that the movement’s strategies draw on the lineage of past protests and resistance tactics in Iran; they are in a dialogue with previous uprisings, while simultaneously transforming and adding new elements to them.

Happiness as a Right

One of the biggest transformations during the uprising was a focus on happiness, and the realization that Iranians deserve to celebrate the joys of everyday life, love, and family, despite the oppressive political system.

This transformation in people’s psyche was a form of protest against the state, whose ideology deploys sadness, pain, and crying to control the imagination of the people. The initiators of this transformation were families of victims of state violence.

Soon after the repression started, videos of the victims were released by their families. Instead of just showing serious portraits, as is the custom with state martyrs, many families shared videos that showed their loved ones laughing, dancing and celebrating life. Even as they mourned and were full of grief, the families presented their mourning as a celebration of life, in the process shifting the tone of the collective performance of resistance.

These videos are a collective curation of visual remembrance – performance protest art done by a nation, led by victims’ families. Instead of choosing to mourn in silence or to only share serious portraits, families shared videos of their loved ones celebrating. This is in direct opposition to the state’s mourning practices as well as state pressure on families to keep silent.

Releasing the videos is itself an act of protest art. Refusing to conform to a narrative of state-enforced seriousness or silent mourning became a performance of resistance.

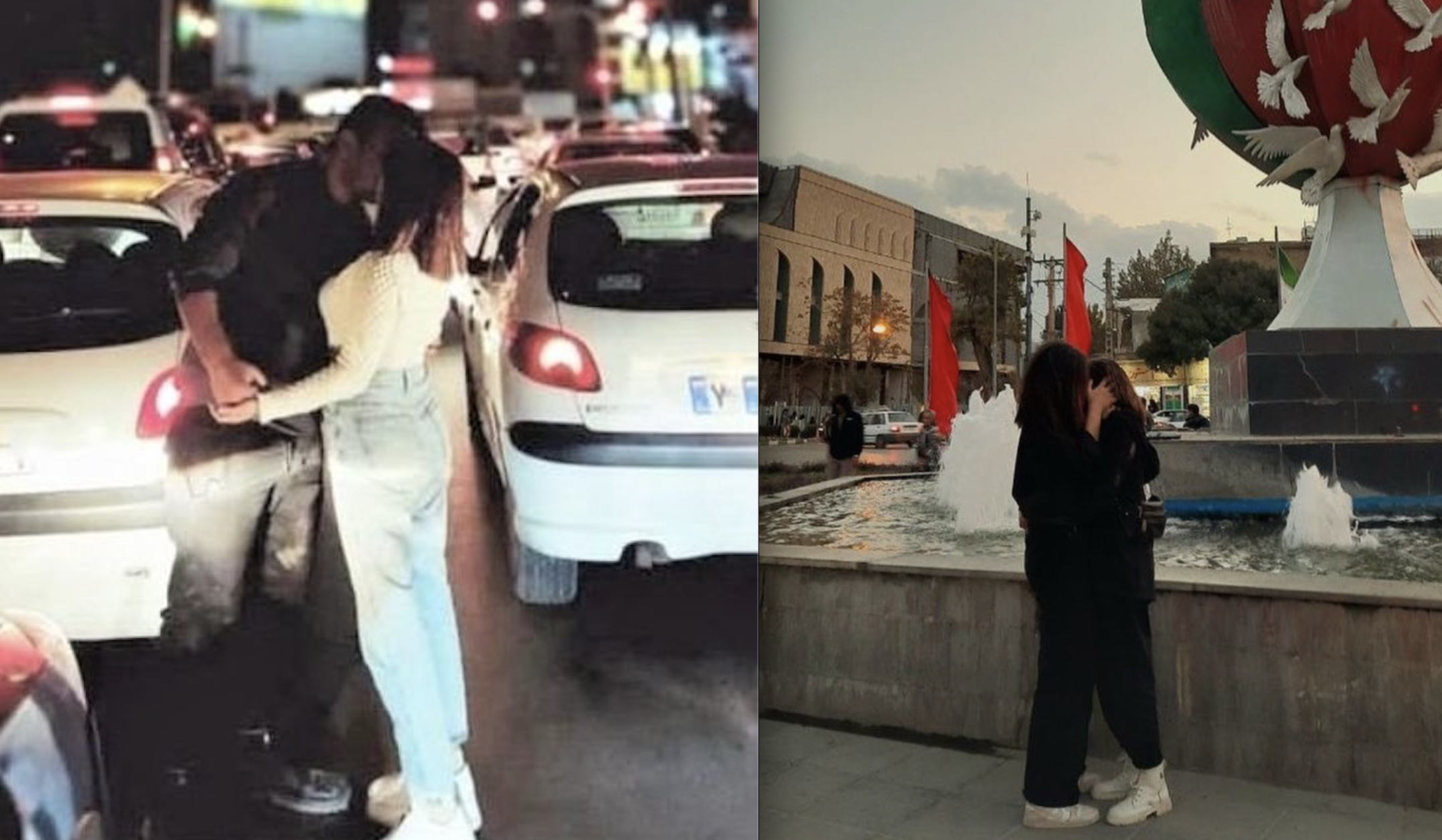

These collective practices of showcasing and performing happiness grew to become something bigger, beyond mourning rituals. Dancing itself became a form of protest art, as these videos from Sanandaj and Tehran show:

Little by little, these forms of happy resistance became daily practices, such as young people kissing on the street. The act of taking a photograph of the moment and sharing it on social media constituted an act of performance as protest.

Re-Enactment as a Form of Protest

In the uprising, art activated space through re-enactment, in the process introducing another genre of art-making. Khodanur Lajaei was an Iranian protester killed during the Zahedan massacre. A picture taken before his death showing him with his hands tied to a flagpole with a bottle of water in front of him (but out of his reach) became a symbol of the ongoing protests.

The photo was taken while he was in custody by police, and the position was meant to humiliate him:

Soon after, students at the Art University of Tabriz replicated the image. Again, protest performance art reversed the context and disarmed the regime’s semiology:

Following the performance art of students at Tabriz University, a chain of reenactments began across the country.

Reenactments continued to the point that during a match in Iran’s Futsal premier league on November 11, a player for the Zarand club made headlines when he struck the pose after scoring a goal. This symbolic gesture was also recreated by a player for the Chuka Talash Football Club after a goal on November 12.

This type of performance grows with decentralized repetition. Different people do similar things in different places and contexts, publicizing and reclaiming particular images and acts to show that resistance is alive, without focusing on the idea of authorship or credit of the act. This repetition has become increasingly common as a protest strategy in recent years.

The Body as Site of Struggle

Another common theme within the Women, Life, Freedom movement was using bodies as a site of struggle. This began with simple, quiet gestures of standing bodies in different corners of the city.

On December 27, 2017, an Iranian woman named Vida Movahed removed her headscarf and stood silently on a utility box to protest against the mandatory hijab while holding her scarf on a stick. She was immediately arrested. In the weeks and months that followed, a series of one-person performances began appearing in different cities where a woman or man stood silently in public space, holding aloft a white scarf, replicating the initial gesture as protest.

Although they kept getting arrested, this gesture kept reappearing. During the recent uprising, this gesture evolved and expanded. It became common to see women holding scarves standing on the streets:

The Gallery as Street

In addition to the art of anonymous protest, Iran also has a large scene of art galleries and institutions which were affected by and partook in the movement. Most art galleries are privately funded and independent of the government. The art world is very active, despite restrictions. Many protesters came from the art world.

The Woman Life Freedom movement occurred soon after the end of the COVID pandemic. Independent galleries already had suffered many financial difficulties. When the movement started, they were just opening up again. During the demonstrations, a debate occurred about the role galleries should or could play.

Some thought that reopening art spaces constituted an act against the movement by gallery owners. Displaying works of art and holding show openings was interpreted as a normalization of the situation of repression. Others, on the contrary, argued that these artistic spaces had been places of resistance against the government for many years, and therefore closing them meant giving in to repression.

When one gallery in Tehran, O Gallery, decided to open again two months after protests began, people came overnight and threw red paint at their door. The next day there were many heated conversations on whether galleries should reopen or not. What resulted was a productive dialogue between artists and galleries. Galleries, with the help of artists, gradually redefined themselves to reflect on ongoing events on the streets.

When O Gallery’s doors opened again, the space transformed into something else entirely. A group of artists were invited to take over the space and build what they wanted, without conditions.

A group exhibition in February 2023 was presented in which no single artist was the creator of the presented work – it was entirely collaborative. As in protest art, the gallery versus artist relationship was suspended and ownership ceased to matter. What mattered was creating webs of solidarity.

Repeating Resistance: Solidarity Beyond Iran

The visual language of Woman Life Freedom unfolded not only within Iran but also spread across Iranian diaspora communities and beyond. These expressions of solidarity, however, occurred in different contexts, which changed the meaning of the actions. The issues raised by this pure mirroring forces us to problematize the question of solidarity from outside Iran, especially among the three to five million Iranians in the diaspora.

In recent decades, when an uprising occurs in Iran, many diaspora artists adopt the visual vocabulary of protest art that they see coming out of Iran. Recently, this has included acts like cutting their hair or stenciling Zhina Amini’s image. This is done with the intentions of keeping the voice of Iranians inside Iran alive. In the process, they repeat that same act or gesture in their new cities without redefining it to their particular contexts. But those same gestures, in the streets of another country, mean something else and function differently. Streets outside Iran are different from streets in Iran; oppression comes from other sources.

In Iran, some protestors burned the veil to oppose the compulsory veiling imposed by the state. But the same act outside of Iran can mean something else. Burning the veil in a country where Muslim communities face state repression may end up promoting Islamophobia against them. Something that in Iran is critical of power, in the United States can actually end up reproducing narratives of oppression enforced by state power.

Showing images of veiled women in galleries in New York, without mentioning the role of US foreign policy abroad or repressive policies at home, can easily become a tool for justifying a “savior” role for the West, in which the historic relationship of Western power to violence elsewhere is effaced. Just as after 9/11, when tropes of “oppressed Muslim women” in Afghanistan became a way for the US Republican Party to rally support for the US invasion of Afghanistan, these images can become PR materials to advance state power and colonialist international policies.

For artists living abroad, myself included, it is important to acknowledge that we don’t live on the streets of Iran and our new contexts require new forms of creativity. The media and institutions that promote our art have their own political agenda. In the Persian-language media world, many channels are directly funded by foreign governments such as the US, Saudi Arabia, and Israel. As a result, if we want to talk about Iran elsewhere, we must simultaneously make those in power around us uncomfortable – the same way protesters in Iran make those in power in their own context uncomfortable.

In the beginning of this exploration, I discussed the act of dying fountains the color of blood in Iran. In that example, an artist picked an element of propaganda art in their surroundings, changed its context, and turned it into protest art. As socio-politically conscious artists, our job is to identify the fountains of our new host countries and through art intervention and creativity shake the systems we live in.

Our job is to address injustices happening in our host countries regardless of whether they are directly related to Iran or not, including topics such as feminism, racism, gentrification, colonialism, and capitalism. In thinking about solidarity across borders, we must remember our contexts and not let any state or power turn our work into a propaganda tool. This is the best way to show solidarity with the Woman Life Freedom movement in Iran.