This article is part of the Indian Ocean series, exploring topics related to the Islamo-Arabic and Persianate world from the perspective of the Indian Ocean littoral and the people who traversed its waters. This series aims to rethink narratives of history and culture, which have been traditionally boxed in by land-based territorial demarcations, and invites readers to imagine the complex interconnectedness of life from East Africa to Southeast Asia and beyond.

The following article was written by Sylvia Wu, a PhD candidate in the Department of Art History at the University of Chicago. Her research focuses on the broader Indian Ocean region, in particular the material cultures of the region’s diverse Muslim communities and their devotional practices.

***

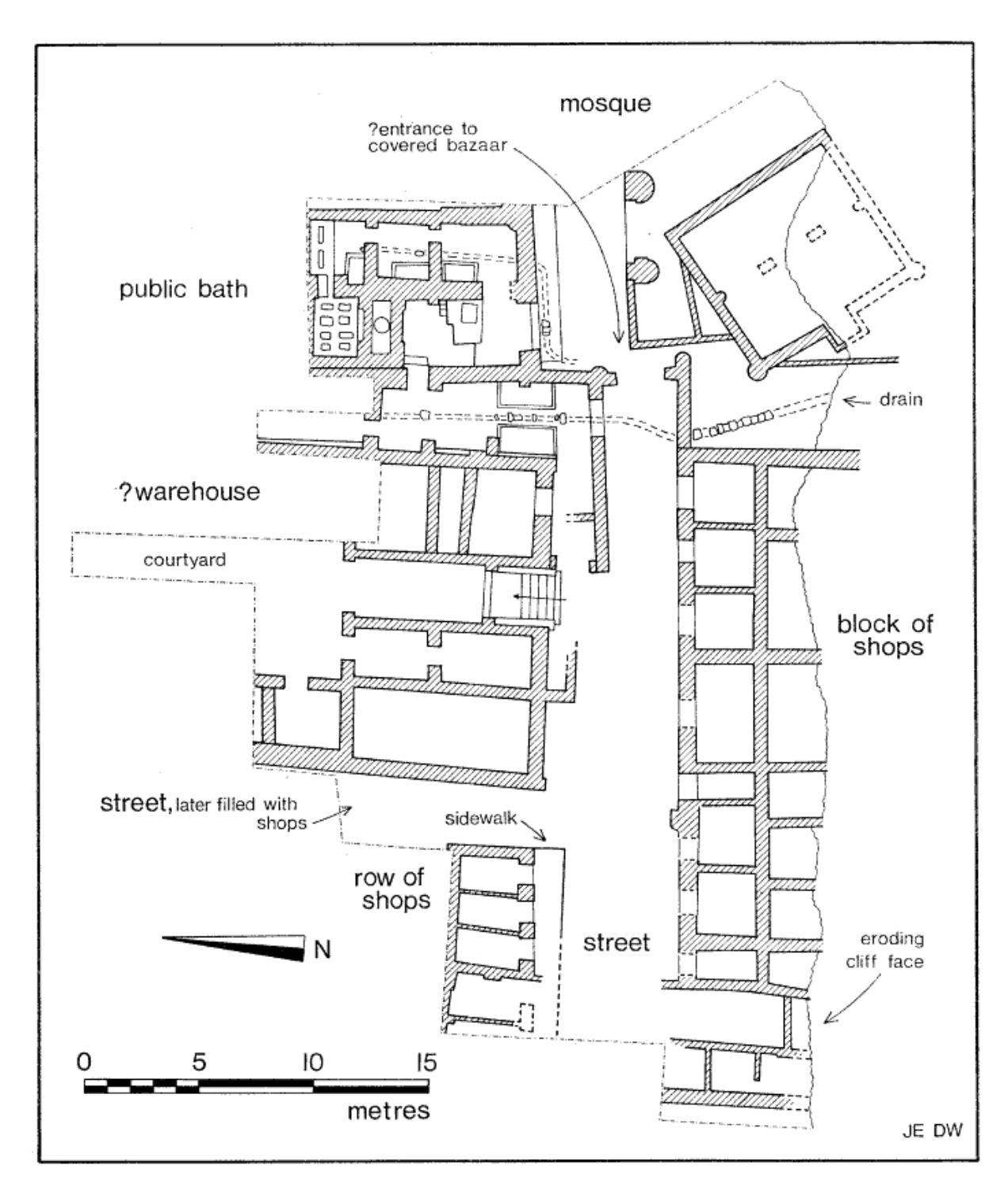

Along the shores of the Persian Gulf, in the port city of Siraf, stands a cluster of mosques unlike any others on the Iranian plateau. Now in ruins, like the majority of the port’s historical sites, these mosques once thrived as gathering centers for the city’s residential and commercial quarters. Built of stone, the mosques’ main prayer spaces range from square to rectangular with a mihrab (prayer niche) salient, that is, a square-shaped enclosure set into the center of the qibla wall (the wall in the direction of Mecca). Built between the 9th and 12th centuries, these mosques were first noted as unique by British archaeologist David Whitehouse who conducted excavations in Siraf between 1966 and 1973 and insisted that the type of stone mosque seen in Siraf could not be found elsewhere in Iran.

Whitehouse’s observation remains undisputed, but the small Siraf mosques are not without parallels. A few precedents exist in 9th-century Iraq. But it is a group of stone mosques along the Swahili coast of East Africa and on the coast of southern China that most closely resemble their Siraf counterparts. These structures share the squarish prayer hall and projecting mihrab that characterize the Siraf mosques, suggesting that these coastal societies were connected through a shared architectural tradition.

While a connection across such a vast distance may at first be surprising, ceramic shards, shipwrecks, and documents have long attested to a maritime economy connecting the eastern and western halves of the Indian Ocean as early as the 900s. A closer look at this network shows that the formal resemblance and commercial ties may reveal not only the transmission of an architectural model but also the multiplicity of exchanges involved in such processes, bringing nuance to Iran’s role as a fulcrum of cultural production in the Islamic world.

Siraf, situated just south of the bustling Iranian metropolis of Shiraz, once served as a vital gateway and commercial hub during the medieval era. This historic port played an important role in the East Africa-Iran-South China connection. Even though Siraf appears to be standing at the heart of the small mosque tradition, the mosques in East Africa and South China bear the name of Shiraz.

In many Swahili towns, such as Shanga, Mombasa, and Kilwa along the coastal regions of present-day Kenya and Tanzania, a widely embraced narrative recounts the establishment of local Muslim communities and their enduring stone mosques by the ruling elite from Shiraz who migrated to East Africa between the 10th and 11th centuries. Similarly, in the southern Chinese city of Quanzhou, home to arguably the oldest surviving mosque in the country, the Ashab Mosque is believed to have adopted its present “Sirafi” layout in the 14th century, thanks to the patronage of a benefactor with roots tracing back to Shiraz.

While the mosques bearing its name have gone on to develop their own lives near and far, Shiraz itself strangely lacks similar architectural exemplars. The enigmatic “Shirazi mosque” resides in the liminal space between existence and absence, truth and myth. Within this curious label, numerous historical strata blend together, and in the following, we endeavor to unravel a few of these layers.

The architectural question

The Shirazi mosques have garnered scholarly attention particularly in the context of the East African coast. A number of Swahili communities assert their descent from a medieval Persian ruling lineage that sought refuge from Iran and went on to establish Muslim dynasties in East Africa. This ancestral connection is commonly referred to as the Shirazi narrative. These communities are often known as “stone towns” due to their remarkable architectural accomplishments, including the construction of houses and mosques crafted from coral or stone. In line with the Shirazi narrative, earlier scholarly interpretations tended to view the Muslim material culture of these communities as a result of Persian colonization. This perspective implied that even the stone mosques were imported directly from Iran.

In recent decades, archaeologists and historians have assembled a body of evidence that effectively refutes the colonization theory. What they have uncovered is that Muslims were already established in the region prior to the presumed arrival of their Iranian ancestors. Moreover, the so-called Shirazi material culture, which includes the distinctive stone mosques, has emerged as a continuation of earlier local traditions, some of which can be traced back to the region’s pre-Islamic era. Adding to this ongoing discourse, a recent analysis of several Swahili burials has introduced another layer of evidence in the form of DNA. This research reveals a predominance of Persian male contributors and African female contributors within the studied group, lending credence to aspects of the oral tradition that speaks of ancestral connections.

However, it is important to note that Persian customs did not supplant the existing East African practices. Scholars working along the Swahili coast have continued to advocate for the centrality of trade-based interactions between East Africa and southern Iran instead of a relationship that uncritically privileges Iranian creativity.

These findings open up new venues for architectural historians to reflect on the crystallization of the Swahili stone mosque traditions, the structures’ intriguing similarities with mosques at Siraf, and further—when the scope of the discussion broadens to include the Ashab Mosque in China—the implications that the East Africa-southern Iran interactions hold for the Indian Ocean network’s Far Eastern actors. For instance, archaeologists have proved the Swahili and Siraf stone mosques were constructed around the same time. Rather than one being a direct derivative of the other, they appear to be contemporaneous developments. This challenges a historiographic bias that has often held up examples from central Islamic lands, such as Iran, as canonical while labeling those from peripheral societies as mere imitations. As we reconsider the validity of the Shirazi narrative, it becomes imperative to reexamine the complex issue of cultural transmission in this context.

East Africa is known for supplying southern Iran with ivory, gold, and construction materials including teakwood and mangrove poles since the late Sasanian period. This economic structure persisted through Iran’s shift into Islamic hegemony. Siraf’s significance grew tremendously over this transition period. By the 10th century, it had outshone other Gulf ports, especially with the Buyids of Fars (934–1062) establishing their court in southern Iran. These trade routes were not limited to the exchange of goods but also included the movement of people. It is therefore conceivable that as the flow of merchandise from East Africa to Iran increased in volume and diversity, skilled laborers like masons and architects, seeking opportunities in a thriving regional hub, might have followed these established routes.

While there is much to uncover, the appearance of small stone mosques at Siraf during this period sparks the speculation that the architectural model might have journeyed from the Swahili coast to Iran, rather than the reverse. This could also explain why this architectural style is not prevalent in Iran’s heartland. It possibly appealed more to smaller, decentered societies like the Swahili stone towns and the merchant groups of Siraf than to the centrally organized, resource-rich inland cities.

To be clear, Siraf did have a substantial congregational mosque. Similar to other monumental examples from the early medieval Islamic world, the Friday Mosque of Siraf boasts a hypostyle design, featuring a central courtyard. The aim of this analysis is not to reverse an Iran-centric approach by eradicating all the agency of Iranian architectural traditions. Instead, it seeks to shed light on the often overlooked and intricate interconnections, or even collaborative efforts, among the coastal communities in question, which in turn promises a more nuanced understanding of Iranian architecture.

The Ashab Mosque in Quanzhou, China provides a comparandum from the other side of the Indian Ocean. Beyond the similar layout with the mosques along the East African coast and at Siraf, an important commonality between the three locations is that they all had established masonry traditions of their own. However, when it comes to the type of stone used, they diverged. In southern Iran, limestone and gray stones were commonly quarried. On the Swahili coast, mosques often employed Porites, a type of stony coral, skillfully cut and shaped. In contrast, Quanzhou was renowned for its granite and green diabase. The ability to work with locally sourced stone materials equipped these communities with the flexibility to experiment with architectural forms that became available during an era of heightened mobility.

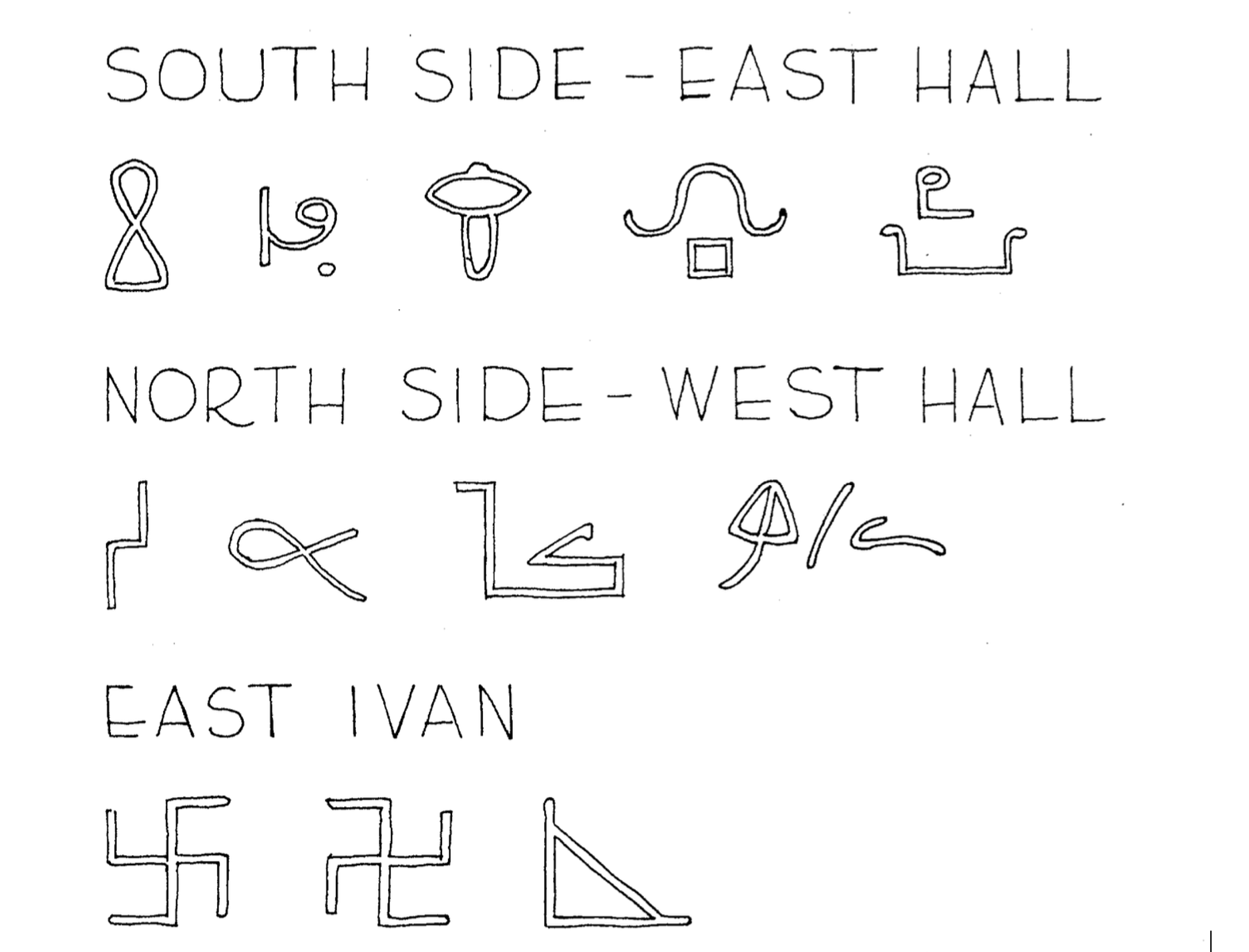

A few textual and material records may shed light on this movement of construction knowledge and skilled masons in multiple directions. In the Kizimkazi Mosque in Zanzibar, a Shirazi mosque, the mihrab features a distinctive floriated Kufic inscription, which is attributed to a calligraphic school in Siraf. The medieval stone foundation of the Masjid-i Atiq in Shiraz reveals mason marks that suggest the involvement of multiple masonry groups hailing from well beyond Iran.

Over in Quanzhou’s Ashab Mosque, the epigraphic program is carved in relief, known as yangke in Chinese. This practice aligns more closely with contemporary architectural epigraphy in North India and Egypt, rather than the traditional intaglio inscriptions, where characters are incised into the stone (referred to as yinke) that were more commonly seen back at home. As far back as the 10th century, the Palestinian geographer al-Muqaddasi noted in his work Ahsan al-taqasim fi ma‘rifat al-aqalim (The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions) that Iranian masons seemed well-versed in the diverse stone textures and masonry techniques of other parts of the Islamic world. As the subsequent centuries brought about more expedited channels for sharing knowledge, this mutual awareness among craftsmen would undoubtedly have deepened.

The phenomenon of the so-called Shirazi mosque is likely a complex process, unfolding in various directions and phases. There is ample room for further exploration into why this particular architectural style predominantly manifested in coastal regions and what distinctions existed between different groups that adopted it. Also beckoning investigation is the vast area between East Africa, the Persian Gulf, and South China—are there other comparable examples in this region, and if so, how might they add layers of complexity to our understanding of Muslim architecture in coastal societies within the context of medieval maritime history?

For now, the striking Siraf-Shiraz axis, which connects the origin narratives of Swahili mosques and Quanzhou’s Ashab Mosque, provides us with a compelling case study. While we have begun to uncover some of the connections, a question persists: why were these mosques named after Shiraz, a city that seemingly played a peripheral role in this architectural tradition?

The myth-making question

No definite answer has been offered to account for the origin of the Shirazi myth. We nevertheless have some clues. As previously mentioned, when we scrutinize the tenuous connections to their eponymous city, it becomes evident that the Shirazi mosques in East Africa had more robust and enduring ties with Siraf, established through centuries of collaborative trade ventures. A similar narrative unfolds in Quanzhou. The southern coastal city stands as one of the earliest Chinese ports to engage in extensive Indian Ocean trade, dispatching goods to Siraf. While the 14th-century foundation inscription of the Ashab Mosque attributes its current configuration to a benefactor from Shiraz, local Chinese accounts make no reference to the Shirazi patron but instead report that a prosperous merchant from Siraf laid the foundation of the mosque in the early 12th century, with an imam native to Kazerun overseeing a renovation in the 14th century.

While archaeological findings cast doubt on the mosques’ association with Shiraz’s architectural heritage, one interpretation of this nominal link is the pursuit of prestige. Some scholars propose that during the period when Shiraz thrived as the Buyid capital between the 10th and 11th centuries, its prominence and affluence may have motivated the Swahili Muslim communities to craft such narratives. Curiously, contemporary sources like geographic treatises and travel reports from the medieval era offer no records of this tradition. The earliest known written accounts of the Shirazi origin story emerge in the early 16th-century Kilwa Chronicles. Here, the narrative unfolds with the migration of a Persian prince from Shiraz, marking the inception of Kilwa’s city-state history. However, the staggering five-century gap between these chronicles and the purported arrival of the prince in the 10th century raises numerous questions about the formulation of the Shirazi tradition. Recent scholarship suggests that the Shirazi label was likely assigned retrospectively. It seems to be part of a broader Persian ancestry legend that took shape as a coherent narrative in 16th-century written sources. These oral traditions likely began circulating widely during the 14th and 15th centuries.

What distinguished Shiraz as a symbol of prestige during that era? By the 14th century, Shiraz had become one of the most revered pilgrimage destinations in the Islamic world. Known as Dar al-‘Elm (the abode of knowledge) and Burj al-Awliya’ (the fortress of saints), the city’s cultural and spiritual landscape was graced by the resting places of numerous luminaries. Among them were renowned poets like Sadi and Hafez, along with descendants of Imam Ali and other revered saints and sages. The convergence of pilgrimage routes with bustling trade networks played a pivotal role in disseminating the city’s sanctity and allure.

This occurred during a period when Indian Ocean seafaring was flourishing—it was more than a historical coincidence that Ibn Battuta traveled 75,000 miles around the globe in the 14th century, much of it by sea, and that the Chinese eunuch Zheng He embarked on his long-distance voyages in the first years of the 15th century. It is plausible that the 14th-century benefactor of the Ashab Mosque in Quanzhou, whether his Shirazi identity was authentic or symbolic, emerged from these dynamic networks. A similar phenomenon occurred in northern India during the 14th and 15th centuries, where the sultanate of Jaunpur came to be known as Shiraz-e Hind (Shiraz of India), providing another instance of the Shirazi label gaining prominence, bridging the regions of East Africa and South China.

The esteemed reputation of Shiraz and its hints of a Persian origin story do not reveal the full picture of events unfolding in the medieval Indian Ocean at the time. In fact, it was often against the strong presence of other actors in the network that the Persian narrative became sought after. For example, engaging both East Africa and China in maritime trade and competing with Siraf was Oman. The Sohar port on the north edge of the Omani coast was among the cosmopolitan entrepôts of the medieval Persian Gulf and vied for control of the East African market.

Notably, an 8th-century trading vessel bearing the port’s name that sailed from Muscat to Guangzhou has recently been transformed into a cultural symbol representing a millennia-old connection between Oman and China and is frequently invoked in diplomatic efforts between the two nations. As for the origin story narrative, it has been suggested that the plot of migrating ruling elites, akin to the Shirazi tradition, was a recurring theme used to narrate the diasporic lineage of newly established medieval states. Pertinently, the 12th-century fiqh (jurisprudence) documents known as the Kilwa Sira (Tradition of Kilwa) recount the tale of two Omani brothers who supposedly played a pivotal role in founding a new dynasty and spreading Ibadism, a school of Islam primarily practiced in Oman, along the Swahili coast. Reflecting on this pluralistic history prompts us to marvel at the resilience and allure of the Shirazi narrative. It managed to stand out among the competing actors and parallel narratives that coexisted within this intricate tapestry of maritime exchange.

Regrettably, the urban history of medieval Shiraz is as cloudy as the truth of the Shirazi legend. How the city’s name became the throughline that strings the Indian Ocean ports together will hopefully be the subject of future studies. A realization nonetheless strikes—while the Shirazi narratives often build around an elite or eminent figure, it was because of the inconspicuous effort of every trader, builder, and pilgrim among other anonymous individuals that the tale turned into powerful metaphors.

REFERENCES

Aigle, Denise. “Among Saints and Poets: The Spiritual Topography of Medieval Shiraz.” In Cities of Medieval Iran, edited by David Durand-Guédy, Roy Mottahedeh, and Jürgen Paul, 142–76. Brill, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004434332.

Delmas, Adrien. “Writing in Africa: The Kilwa Chronicle and Other Sixteenth-Century Portuguese Testimonies.” In The Arts and Crafts of Literacy, edited by Andrea Brigaglia and Mauro Nobili, 181–206. De Gruyter, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110541441-006.

Horton, Mark. “Early Islam on the East African Coast (750 -1200).” In A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, edited by Finbarr Barry Flood and Gülru Necipoğlu, 262–68. Blackwell Companions to Art History. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2017.

Wu, Sylvia. In the Name of Shirāz: The stone mosques of the East African coast reconsidered. Postmedieval 13, 497–515 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41280-022-00252-0.

Wynne-Jones, Stephanie, and Jeffrey Fleisher. “Eastern African Coast.” In The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Archaeology, by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Jeffrey Fleisher, 376–94. edited by Bethany J. Walker, Timothy Insoll, and Corisande Fenwick. Oxford University Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199987870.013.15.