Part II of III in a series on Slavs and Tatars‘ Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz– a multiplatform exhibition, lecture-performance, and publication looking at the unlikely shared story of Poland and Iran. The exhibition opens at REDCAT gallery at the Roy and Edna Disney Theater/Cal Arts in Los Angeles on February 9th and runs through March 24th, 2013 before moving to Vancouver’s Presentation House from April 13th to May 26th, 2013. For more from Slavs and Tatars, check out “Polish Shi’ite Showbiz: Slavs and Tatars on Solidarność & the ’79 Revolution.”

The post below contains Slavs and Tatars’ first audio piece, Samizabt, a tribute to the legacy of poetry as a means of political resistance. A series of Polish poems written by Nobel prize winning authors such as Szymborska, Milosz, as well as Rozewicz and Zagajewski, were translated for the first time into Persian and recorded by a noheh-khan. Samizabt was prepared for the Frozen Lakes group exhibition at New York City‘s Artists Space, which opened on January 13.

A look at the common heritage of Poland and Iran, from the 17th century to the 21st, Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz continues to play a pivotal position in our practice. Midwifing the evolution of our initial interests in excavating hitherto overlooked histories into a multi-platform offering, the project is more redolent of a souk than an exhibition: instead of the traditionally precious focus on a single work, there is something for everyone. To do justice to this intricate story, we turned to a similar fanning out of media: from a magazine contribution to a balloon, an archive to textile works, public billboards to lectures, publication to craft-specific sculptures.

We have studied, adopted, revised and employed several precedents where craft or folklore traditions are shared between the peoples of Iran and Poland: from pająks to reverse-glass painting and banners. If, for example, the pairing of these two countries’ recent histories strikes an off-key note, the unlikely affinities between Shi’ism and Catholicism only pours further fuel on dissonant fires. Scholars of Shi’ism, from Seyyed Hossein Nasr to Henri Corbin, have often pointed out areas of overlap, from the idea of transubstantiation to the proliferation of saints and their veneration.

If (Sunni) Islam was a reformation, a correction of sorts to what some deemed the excessive idolatry of the Christianity of the times, then Shi’ism’s role as counter-reformation becomes more vivid. Shi’ism Christianised Islam both theologically with the re-introduction of mystical gnosis or the return of the twelfth imam, or Mahdi, as well as formally with its less doctrinaire view on figuration.

Far from the tacit dismissal of handicrafts and folklore that has often characterised the modern project, Slavs and Tatars tend to see no less than the currents of history, political emancipation, and ideology in these otherwise discreet craft objects and practices. Some of these traditions – such as the mirror-mosaic – have been instrumentalized for ideological ends.

Imagine walking into former palaces of the Shah or Shi’ite shrines, where the entire 1000 square meter interior with soaring 8 meter high ceilings, is made of mirror mosaics. Each single piece of mirror is roughly 2 centimeters squared, leaving no part of the wall visible. You would be forgiven for thinking you’ve walked into a Swarovski boutique year 4000 A.D.

The geometric patterns, upon which the mirror mosaics are based, spread across the region with the rise of Islam in the 7th century, linking the architectural traditions of diverse civilizations.* In North Africa and the Gulf, today, one often comes across wood or ceramic as the medium of choice for this sacred geometry. The Persians, always keen to distinguish themselves from their Arab neighbors, opted for mirrors as a more beveled, bling-bling version if you will.

The mirror mosaic best exemplifies the complexity behind the Islamic Republic’s particular brand of anti-imperial imperialism. Much like the Russian Revolution, the Iranian Revolution of 1979 was a liberationist revolutionary ideology that was subsequently exported beyond its borders. It’s a very interesting dynamic: foreign powers or influences are kicked out before one’s own ideology takes on the airs of those same foreign powers. In this case, several elements of the Iranian Revolution have been exported to the greater Muslim world.

In a long-lashed wink at the Soviets, the Islamic Republic of Iran positions itself as a champion of the oppressed and exploited throughout the world. Today, the IRI exports this craft as the aesthetic embodiment of its own ideology to Shi’ite shrines throughout the region such as the Sayyida Zeynab Shrine in Damascus.

For the “Frozen Lakes” exhibition at Artists Space in New York, we turned to another, albeit less considered, craft shared by both countries: that of poetry and its instrumentalisation as a form of political resistance. Just as our banners stitched, embroidered, and needle-pointed the best-practices of Poland’s Solidarność movement for the Islamic Republic’s crisis of legitimacy and direction, we turned to the poetry of Communist-era Poland for its ability to deliver a searing critique all the more forceful for its oblique, lateral punch.

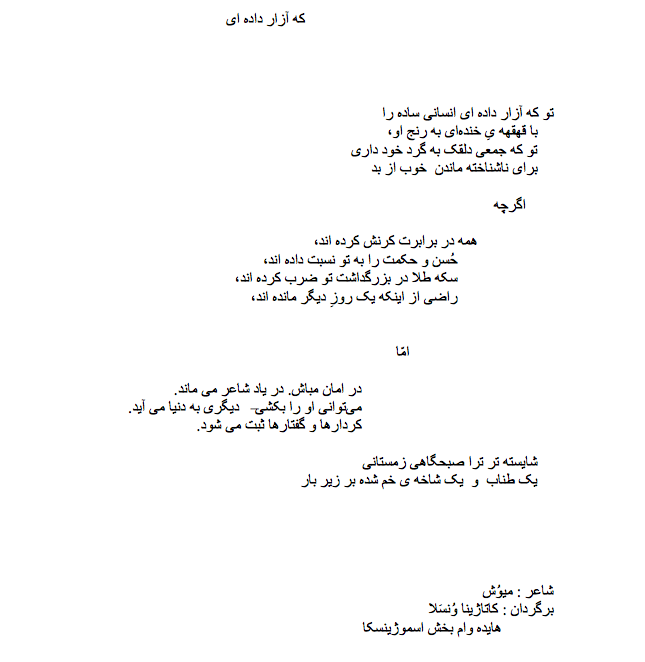

Like Iranian cinema of the 90s, Polish poetry never addressed political issues frontally but couched its critique in allegory, metaphor, or subtle allusions. Translating the likes of Nobel Prize winners Czeslaw Miłosz and Wisława Szymborska, Tadeusz Różewicz and Adam Zagajewski into Persian, we produced

our first sound piece, called Samizabt (You Who Wronged), based on a 1950 Miłosz poem.

Samizabt – Slavs and Tatars [ca_audio url=”http://ajammc.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Milosz.mp3″ width=”750″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

Installation view at Artists Space as part of Frozen Lakes, January-March 2013

Photo: Daniel Perez

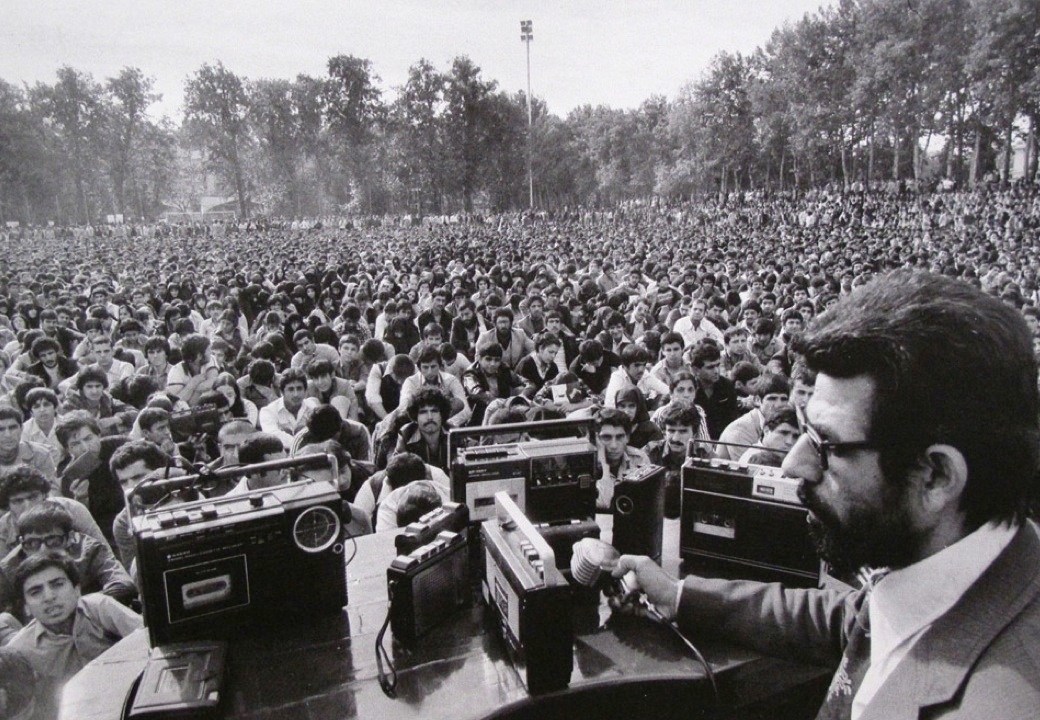

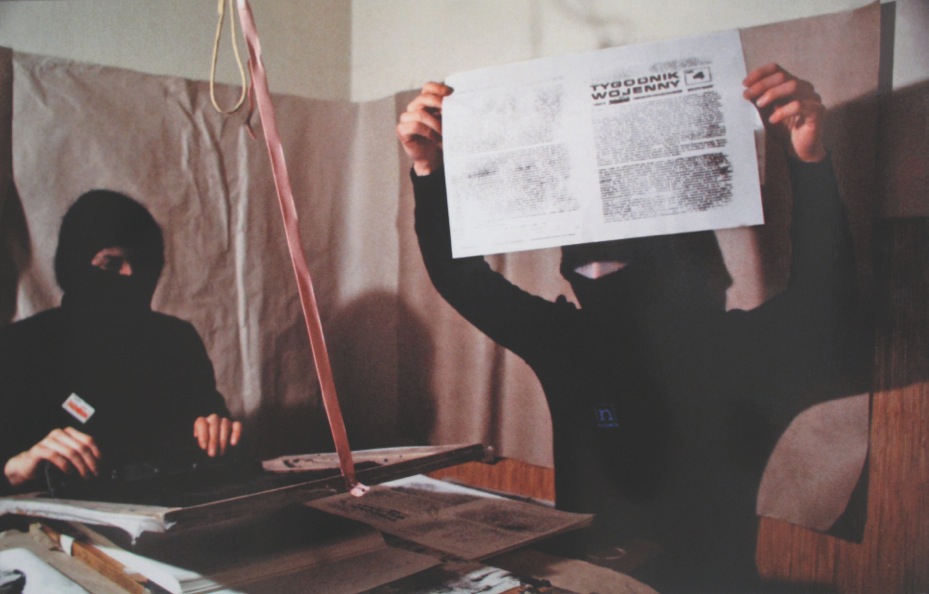

The tradition of dissident poetry is a storied one: the title Samizabt pays tribute to the samizdat or self-published, underground, unofficial transcripts of literature circulating around the former Soviet Union. Khomeini’s famous sermons–Iran’s own samizdat–were smuggled into Iran on audio-cassette in the years prior to the revolution while it was a softer version of redemption delivered in the first rock and roll concert in the Eastern Block, at Poland’s Jarocin festival in 1986. Even Hafez, whom Iranians have stripped of all politics in their bear-hug of the poet’s verse, on more than one occasion took a swipe at power, for example with his iconic stanza on Tamerlane’s golden achievements:

اگر آن ترک شیرازی به دست آرد دل ما را

به خال هندویش بخشم سمرقند و بخارا را

That beautiful Shirazi Turk took control and my heart stole

I’ll give Samarkand & Bukhara for her Hindu beauty mole

(translated by Shahriar Shahriari)

Against a tidal wave of expanding emphasis on the visual, the wordsmith’s trade is proving itself surprisingly resilient. Able to carve out entire regions of dry land from the flood of language, the poet sees in the combination of letters a soapbox from which to stand.

For Slavs and Tatars, language remains a craft unto itself: be it the emphasis on process tantamount to handiwork; its ability to jam time, and thereby conceal as much as reveal, meaning; its talismanic hold on us as wholly other, or its sometimes DIY aesthetic. The performativity of carving words from the composite languages in our otherwise linguistically spoiled geographical remit of Eurasia has been equally important to our research and our works.

Czesław Miłosz – Washington D.C., 1950

Który skrzywdziłeś

- Który skrzywdziłeś człowieka prostego

- Śmiechem nad krzywdą jego wybuchając,

- Gromadę błaznów koło siebie mając

- Na pomieszanie dobrego i złego,

- Choćby przed tobą wszyscy się kłonili

- Cnotę i mądrość tobie przypisując,

- Złote medale na twoją cześć kując,

- Radzi że jeszcze dzień jeden przeżyli,

- Nie bądź bezpieczny. Poeta pamięta.

- Możesz go zabić – narodzi się nowy.

- Spisane będą czyny i rozmowy.

- Lepszy dla ciebie byłby świt zimowy

- I sznur i gałąź pod ciężarem zgięta.

You Who Wronged

- You who wronged a simple man

- Bursting into laughter at the crime,

- And kept a pack of fools around you

- To mix good and evil, to blur the line,

- Though everyone bowed down before you,

- Saying virtue and wisdom lit your way,

- Striking gold medals in your honor,

- Glad to have survived another day,

- Do not feel safe. The poet remembers.

- You can kill one, but another is born.

- The words are written down, the deed, the date.

- And you’d have done better with a winter dawn,

- A rope, and a branch bowed beneath your weight.

*Editor’s note: this sentence was revised to reflect the diverse origins of geometric design.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Slavs and Tatars is a faction of polemics and intimacies devoted to an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia. The collective’s work spans several media, disciplines, and a broad spectrum of cultural registers (high and low) focusing on an oft-forgotten sphere of influence between Slavs, Caucasians and Central Asians. Slavs and Tatars has published Kidnapping Mountains (Book Works, 2009), Love Me, Love Me Not: Changed Names (onestar press, 2010) ), Not Moscow Not Mecca (Revolver/Secession, 2012), Khhhhhhh (Mousse/Moravia Gallery, 2012) as well as their translation of the legendary Azeri satire Molla Nasreddin: the magazine that would’ve, could’ve, should’ve (JRP-Ringier, 2011). Their work has been exhibited at the Frieze Sculpture Park, the 10th Sharjah, 8th Mercosul, 3rd Thessaloniki, and 9th Gwangju Biennials.

After devoting the past 5 years primarily to two cycles of work, namely, a celebration of complexity in the Caucasus (Kidnapping Mountains, Molla Nasreddin, Hymns of No Resistance) and the unlikely heritage between Poland and Iran (Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz, 79.89.09), Slavs and Tatars have begun work on their third cycle, The Faculty of Substitution, on mystical protest and the revolutionary role of the sacred and syncretic, for group exhibitions at the GfZK, Leipzig and the New Museum Triennial as well as recent solo engagements at Secession, Vienna (Not Moscow Not Mecca), MoMA, NY (Beyonsense), and Moravia Gallery, Brno (Khhhhhhh). Their 2013 engagements include, among others, a solo exhibition at Künstlerhaus Stuttgart and group exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou and Kunsthalle Wien.

5 comments

Beautifully written piece, both relevant and insightful. However, I urge the author to consider a historical detail:

Today architectural historians have a unanimous view about the derivative nature of Islamic art, at least at its foundation. Ceramic, horticultural, and architectural styles were systematically imported and appropriated from Sassanian and Byzantine models in the Near East, and to a lesser extent North African styles especially in the Maghreb. This includes but is not limited to the domes, squinches, iwans, archways and vaults that we see here, all of which have well-documented Sassanian precedents and the former three of which were actually Iranian inventions (the latter two were adopted by early Muslim architects from a Sassanian milieu).

The “geometric designs” referred to here that are characteristic of mosque architecture are professionally called “muqarnas” or “honeycomb” vaults. Contrary to what is proposed, this feature did not spread “with the rise of Islam in the 7th century”. The earliest examples of full-fledged muqarnas designs seem to have developed almost simultaneously in Iran (Takht-i Suleyman) and North Africa at beginning of the 10th century, although both of these developments probably resulted from a string of innovations on extant Sassanian vaulting techniques that were widespread in the Near East. An intermediary of this process was recovered from 9th century Nishapur in eastern Iran, which remains the oldest example of honeycomb vaulting in the world (see Ulrich Harb; Oleg Grabar). These findings support the yet-unconfirmed but nonetheless reasonable notion held by some architectural historians that the decorative stalactite ceiling or muqarnas vault may have been introduced to Egypt and North Africa from Baghdad/Iran by the Fatimids in the 10th century (See Kupier; Grabar).

What’s more, Al-Kashi, a 14th century Iranian mathematician and astronomer from Kashan, is the first to document and analyze the muqarnas vault, one of the four main types of which he assigns a suggestive toponymic epithet: “Shirazi”.

Thus to refer to the muqarnas vault as a product of “diverse civilizations” due to the “diverse origins of geometric design” in the editor’s note (note: this was edited from “Arab”) is to almost purposefully obscure not only the known history of the design in question, but an accepted narrative of cultural appropriation–that is, both pre- and post-Islamic Iranian models informing those of the rest of the Islamic world; the acknowledgement of which might in some way undermine the author’s follow-up remark on Iranians’ materialistic character compared to “their Arab neighbors”. So based on the factual history, we can view the incorporation of mirrors onto the muqarnas vault as an internal innovation in native architectural vocabulary, rather than a glitzy or distasteful Iranian reaction to an “imported” canon as the article suggests. I think the article should acknowledge the distinct Iranian role in these historical developments in a second edit, and separate tongue-in-cheek ethnic commentary from architectural history.