The following is a photo essay by Ali Karjoo-Ravary, a PhD candidate in Religious Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. His research focuses on late medieval Sufism in Anatolia and the greater Persianate region. The following photographs are part of a larger forthcoming project about public rituals in the Islamic world. Follow him on twitter at @akarjooravary. The accompanying article was written by Ajam co-Editor-in-Chief Alex Shams.

For the nearly 200 million Shia Muslims around the globe, the month of Muharram is one of the most intense periods of the Islamic calendar. Nowhere is this more obvious than in Iran, where around 90% of the country’s 75 million people are adherents to the faith and where it has a privileged place in public life.

During this time, Muslims of all backgrounds participate in a series of rituals observing the martyrdom of Husayn ibn ‘Ali, the grandson of the prophet Muhammad, and his companions at the Battle of Karbala in 680 A.D. As a violent culmination to a political struggle between the family of the Prophet and the Umayyad Caliphate, the tragic events were soon commemorated by the inhabitants of Kufa, who failed to come to the aid of Husayn.

Although Muharram and the events around the martyrdom of the Islamic figure Husayn have an importance for all Muslims, for Shias the story has taken on a central importance given that many Shia Muslims imagine their community’s history as one of widespread and recurrent persecution at the hands of the political leaders of the global Islamic majority.

This narrative of longstanding suffering is embodied for many in the martyrdom of Husayn, which is widely interpreted not merely as a battle between two historical figures but instead as an epic struggle between justice on one side and oppression on the other.

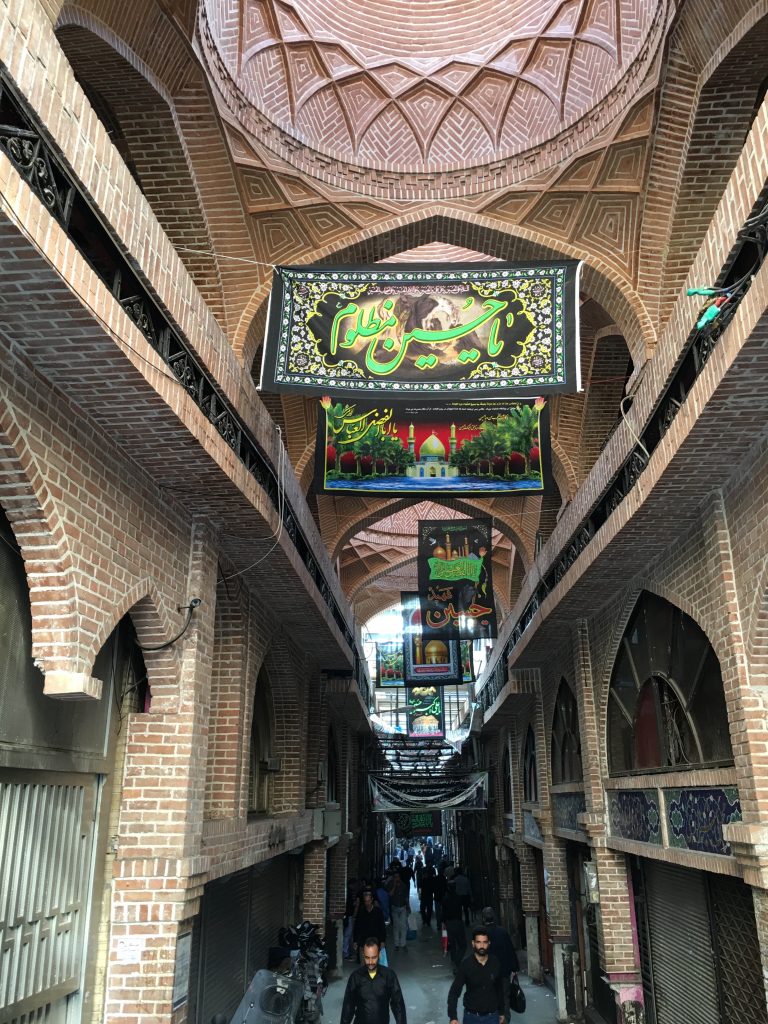

The day of Husayn’s death, Ashura, is just one of the many days dedicated to the tragedy of Karbala. The lamentations end on December 2nd (21st of the Islamic month of Safar), forty days after Ashura. On Arba’in, “the fortieth,” millions of people come out on the streets one final time to mourn the death of Husayn. The photographs below depict Muharram observances and preparation across Iran in October of 2015.

The lamentations of Karbala play a pivotal role in Shi’i religious cosmology. It is the moment when History took a wrong turn — when temporal and divine authority diverged.

From this perspective, the tragedy at Karbala encapsulates all the injustice of the world, through which all future political and social events can be seen. In honor of this perceived sacrifice, many contemporary mourners re-enact versions of the suffering experienced by Husayn’s followers. This can take the form not only of fasting or self-flagellation, but also full-scale re-enactments of the events themselves.

In the vast majority of places where Shia Muslims today live, they constitute a minority. In recent years, processions marking Ashura and Arba’in have taken on increasing political significance. These processions are frequently subjected to attacks by anti-Shia groups (including attacks in Bangladesh, Nigeria, Iraq, Pakistan, and elsewhere this year alone), in the process often blending together the remembrance of pain and suffering in the past with that in the present.

In Iran, the days of mourning were politicized during the tumultuous events of 1978 and 1979, when the Muharram observances provided a platform for many Iranians to express their discontent with the Shah during the period that came to be known as the Iranian Revolution.

In the years following the establishment of the Islamic Republic and the beginning of the Iran-Iraq War, the rituals of Ashura and Arba’in became occasions in which millions could participate in collective mourning. In the course of the eight-year war nearly a million Iranians were killed, and the rituals became a cathartic experience for the millions who took part. Just as during the Revolution, the sense of suffering for justice became embodied for Iranians in an extremely physical way, and Ashura allowed the pain of wartime to be expressed publicly and collectively.

A popular saying often attributed to Husayn’s son, the fourth imam, is that “Every day is Ashura, every land is Karbala,” meaning that injustice is everywhere at all times and must be fought against. For Iranians during the Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War, this expression became a central part of their understanding of their self and of their nation. By recreating the pain of Karbala every year on the streets of Iranian cities, the public sphere became sacralized and marked the repeated and recurrent memorialization of the sacrifices of the heroes of early Islamic history.

Following the end of the Iran-Iraq War and the return of normalcy to the country, the processions lost some of their intensity, particularly for those who came of age in the years that followed. But every year without fail they continue to be held in almost every neighborhood of the country, organized by the same local committees that participated in the Revolution and later provided a recruitment base for war martyrs.

For the less devout, the mourning processions have faded into the background of everyday life, where they constitute just another of month of sacred rituals and traffic jams in a country where religion pervades the public sphere year-round. But for many other Iranians, the month continues to retain a special significance.

This is particularly true for those Iranians who are among the more than 2 million who visit Iraq yearly for pilgrimage to the tombs of Husayn and other figures associated with early Islamic history. In Iraq, the Arba’in procession between the holy cities of Najaf and Karbala regularly draws around 20 million people, including Iraqis as well as Iranians, Pakistanis, Indians, Azeris, Afghans, Bahrainis, Lebanese, and many more from around the world. Although overwhelmingly Shia, the procession also draws participants from Sunni, Christian, Mandaen, Sabian, and other religious groups present in southern Iraq.

But for Shias in particular, this display of numbers is also a display of power. For those coming from countries where they are persecuted minorities, Arba’in one of the few times when they are able to interact with millions of others who share their beliefs. Along the way, Iraqis open their homes to pilgrims and offer food and drink all along the way, reinforcing the bonds between worshipers. Under Saddam Hussein’s regime, the processions were banned, but once they began again in 2003 they attracted record numbers and today Arba’in is one of the most well-attended religious occasions on Earth.

For Iranians — including the 1.3 million headed to Iraq for Arba’in alone this year — participating in rituals in Iraq also brings them face-to-face with anti-Shia persecution they otherwise rarely encounter. Shia religious commemorations and neighborhoods in Iraq are subject to frequent bombings, especially during Muharram, and for many Iranians the trips to visit holy shrines are filled with the threat of danger.

This form of pilgrimage reinforces not only transnational Shia solidarity, but also the sense that Karbala is really here, and Ashura is really now.

At times of political turmoil in Iran, like in the Iranian Revolution or during the Green Movement in 2009, the processions can take on a subversive political significance. The example of Husayn is utilized by participants to make a point about the oppressors they see in the present day.

The processions in the streets of Iranian cities sacralize public space and encourage worshipers to imagine that history has by no means ended, but continues forward in the present day. For those less taken to grandiose political narratives, the processions are also just a public event like a parade and an opportunity to see friends and neighbors and maybe catch up on gossip.

How Ashura is understood is a matter of interpretation for each individual participant. And for many, it is probably some combination of all of the above, more than any individual component.

1 comment

Excellent stuff, as always Ajam