The following article was written by Sanaz Sohrabi, a filmmaker and researcher of visual culture born in Tehran. She has done extensive archival research at the British Petroleum Archives engaging with the history of photography and film practices of British-controlled oil operations in Iran. For more information, visit her website.

***

For those who grew up in Khuzestan or have relatives from the southwestern province in Iran, oil stands for many things; it is always a placeholder for something intangible and beyond its material dimension. Oil is a story: childhood memories, the oil company’s special school stationery for workers’ children, familial migratory paths, or night picnics by the “gas flares” popularly known as “Atisha” in Ahvaz. Oil has a residual effect on memory for those who have lived in proximity to it. My maternal family hails from Shushtar, a small city known for its Roman ruins and multilayered historical sites ranging from pre-Islamic water mills to beautiful Islamic architecture such as Emamzadeh Abdollah Mosque, with my extended family scattered in different cities across Khuzestan.

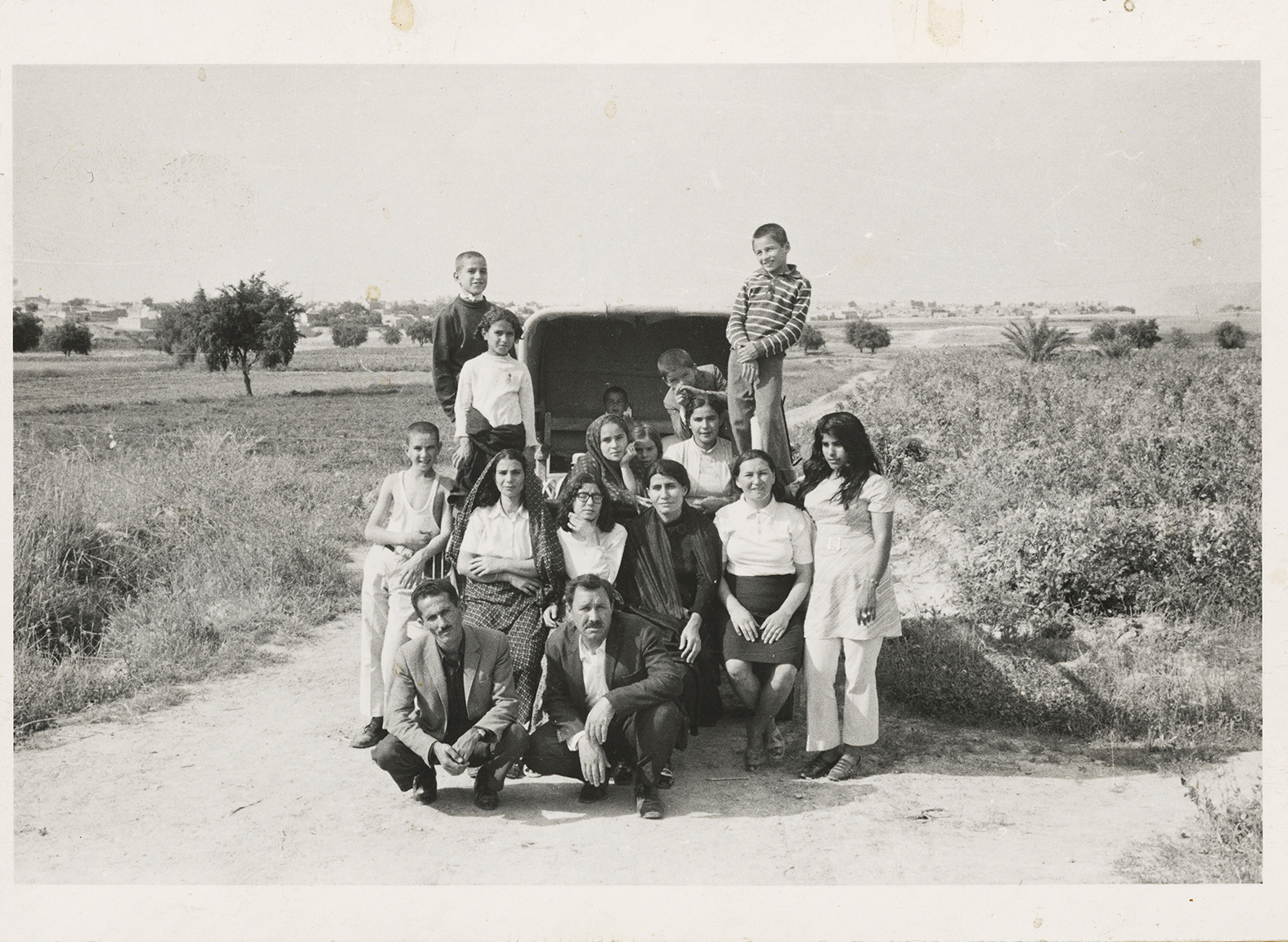

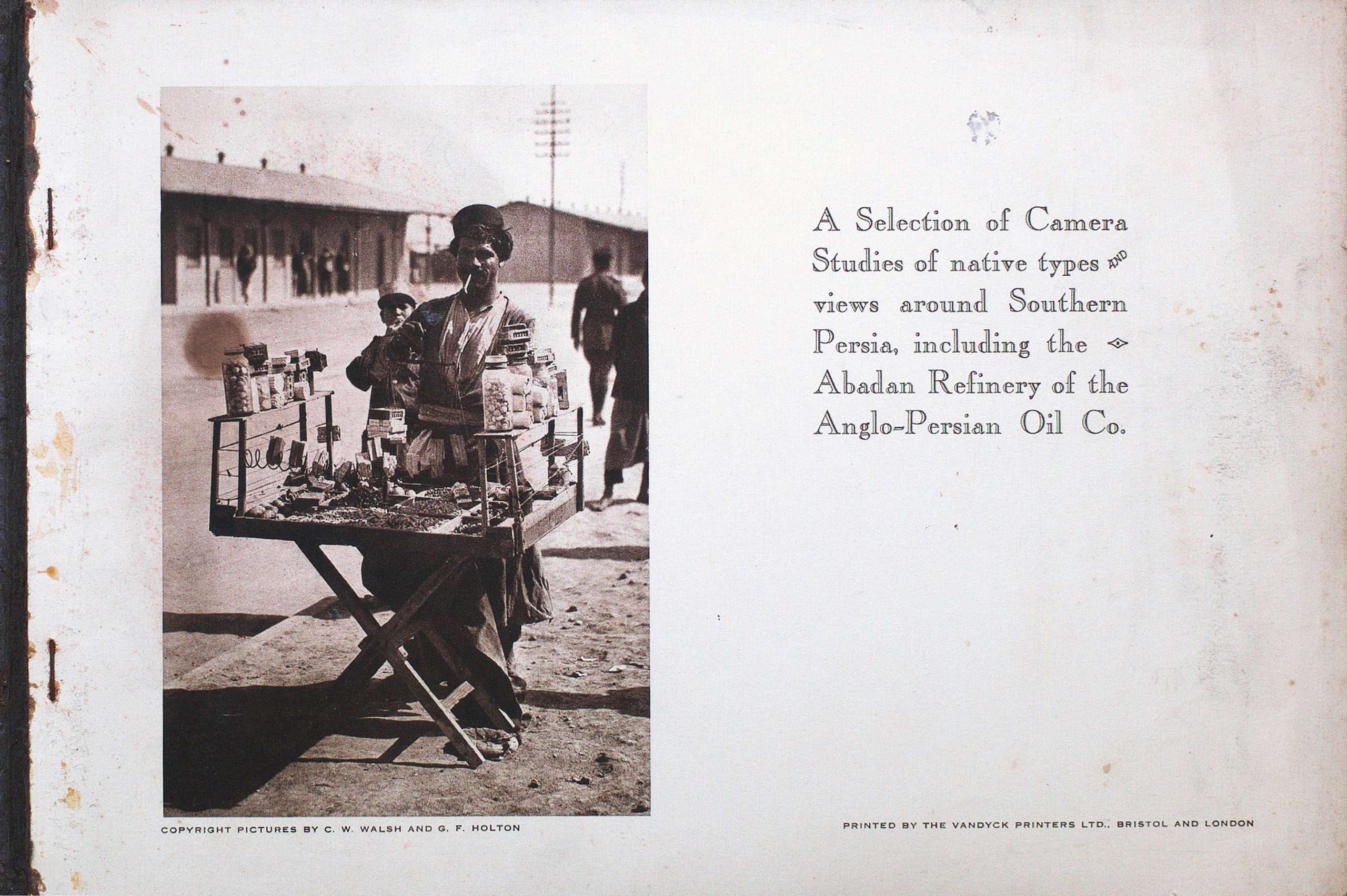

This connection perhaps was a mental starting point when I embarked on my current doctoral research project, which is an ethnography of the visual history of the Iranian oil industry through the prism of the archives of British Petroleum (BP), which started its operations in Iran in 1908 until the nationalization of the oil industry took place in 1951. But the BP Archives never encompassed the full picture for me. I started with the archives only to arrive back at my family and to record what I had missed or had taken for granted throughout my childhood. I arrived back to stories and images which were often framed through nostalgic remembrance of the past when the petro-utopia of Abadan was raved about as the greatest refinery in the world or how petromodernity’s seemingly prosperous economic machinery had brought cultural and social amenities to those who worked for the oil company, fueling the rapid and violent modernization of Iran between 1960-1970 (Fig. 1).

I grew up listening to these stories from my uncles and relatives who had worked for the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), renamed from Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) to NIOC after the nationalization of the oil industry took effect in 1951. I would often find objects with the NIOC logo on them in our household. The prevalent nostalgic image of oil is deeply troubled by a violent extractive logic whose past has been pushed to the margins of history by both the national and corporate narratives, rendering invisible the unequal social footprints and ecological devastations caused by the oil industry set against its colonial legacy. The story of oil’s establishment in Iran sheds light on how corporate narratives of beginnings are colonial constructs used to marginalize other forms of historical storytelling that can reveal social experiences of oil from the perspectives of oil-producing countries in Western Asia and North Africa.

When I first visited the British Petroleum Archives, I was equally fascinated to visit the main BP headquarters in central London. British Petroleum has been able to fabricate a threshold of liability between its colonial history and contemporary brand as “Beyond Petroleum,” moving forward into its petroleum-free future at the expense of so many invisible lives in the shadow of its historical trail. I was keen to see for myself how the British colonial legacy of extraction of oil is hiding in plain sight in the heart of the former empire, and how an energy enterprise so central to the British empire’s modern extractive complex in its final decades has been able to rebrand itself in the present moment.

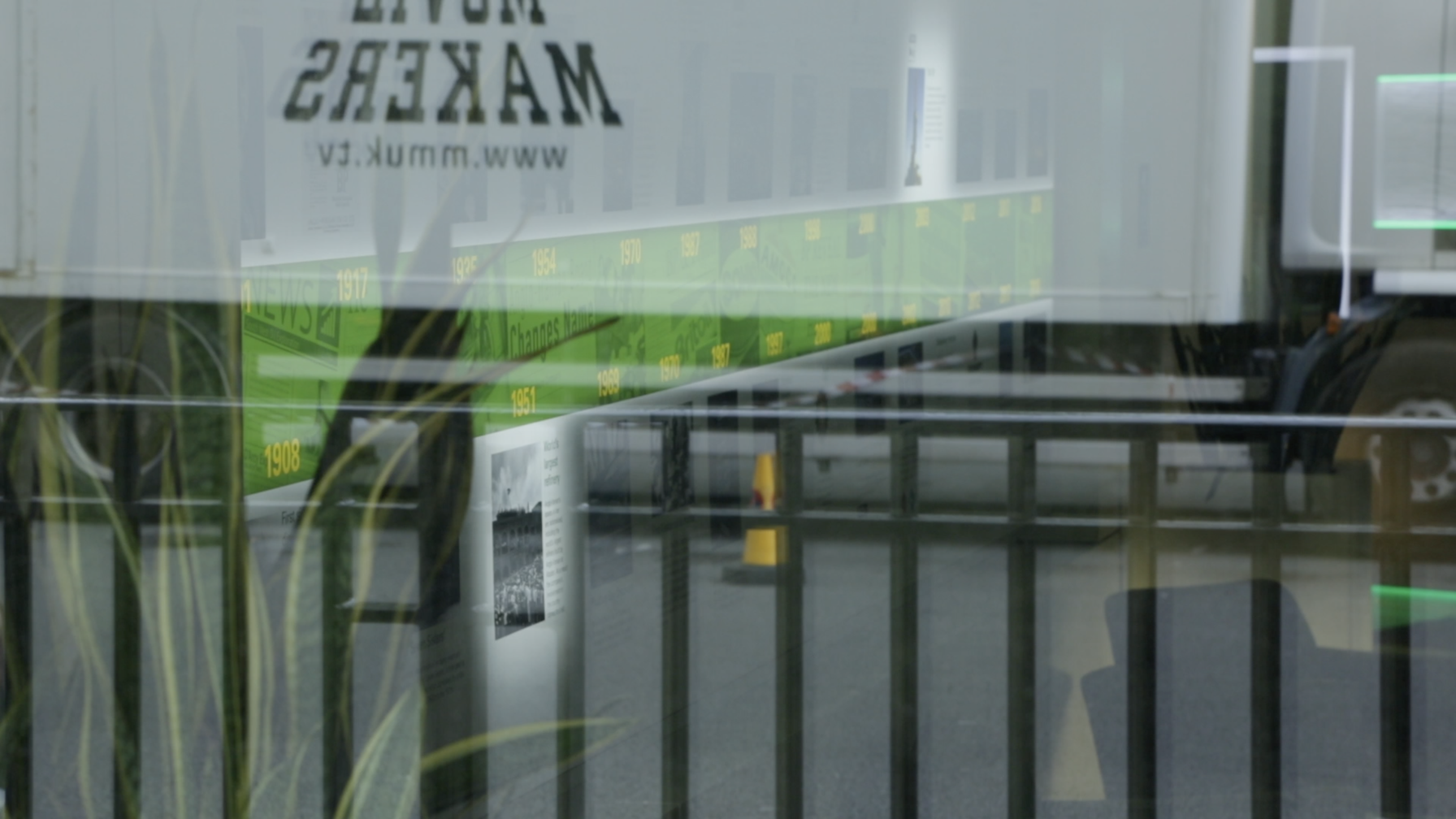

Upon arrival at the BP headquarters building, I was struck by the fact that there was not much to see. The building was seemingly just like any other building in central London. However, by peeking inside the street-level windows, I noticed that there was a long photo-text installation inside the lobby rather invisible to passersby outside. The installation consisted of photographs and texts forming a timeline; an automated light highlighted what seemed to be different milestones of BP’s history ranging from the first eruption of crude oil in Iran, followed by periods of transitions, oil crisis, and technical achievements, up until the company’s projected outlook toward future green-oriented energy projects (Fig.2).

Much like a timeline, BP’s linear story started from a point of departure, a calendrical marker of oil’s early establishments, moving onward into the future. The first calendrical marker was the infamous photo captioned and titled by BP as “Gusher” (Fig. 3). The photograph of “oil well Number. 1” in Masjid Suleiman, Khuzestan seemingly erupting with its first flow of crude oil on May 26th, 1908, has been repeatedly reproduced and used as an iconic moment in different historical volumes and publications written about the history of the Iranian oil industry. An exhausted image establishing the intertwined ‘beginnings’ of Iran’s oil industry and British Petroleum. Images of crude oil’s eruption such as “Gusher,” which were a common visual proof for the prosperity of oil, continue to monumentalize extraction as an event and a matter of the past, ignoring the reality that extraction of oil is not simply a visual event, but rather a longue durée event.

This official timeline of BP indicates a preoccupation with the notion of commencement, a point in time wherein the company can establish a before and after of oil. This kind of chronology allows for a separation between modern and the non-modern visions of Iran according to BP, which facilitates and advances the company’s homogeneous narrative of exporting petromodernity to other nations lacking the technical expertise to extract its riches.

Colonial temporal logics have always condemned their subjects to a pre-history; one that can not be represented or situated via the modern systems and logics of distribution of time. More so, here, to imagine and allow for a post-petroleum future to emerge for BP, the company uses the archives to visualize and justify its historical narrative of petromodernity set against decades of ecological and social dispossession and eradication.

The prelude to the Iranian crude oil story was shaped and imagined in other geographies of extraction at the disposal of the British empire. The extensive geological explorations in Iran’s concession area, granted to Britain for sixty years in a vaguely defined legal framework and with controversial terms, became possible due to the already-existing colonial network of the British empire and its ports, water gateways, and infrastructures of transportation across the African and the Asian continent (Fig.4). The history of Iran’s oil industry and its establishment in 1908 as Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) foregrounded the cusp of a new global energy complex based on crude oil; one that shaped so much of the political economy of oil as it is operated globally up to this day.

The blueprint of our current fossil fuel dependency has a long colonial background whose ecological ruination and social inequalities are still haunted by the specters of its colonial legacies. This colonial backdrop against which petroleum has become the sole most important energy commodity of the current era has been rendered invisible in the grand institutional, national, and corporate narratives by major energy enterprises such as British Petroleum or Royal Dutch Shell, another major energy corporation with a troubled colonial trail in Asia and Africa. This petro-utopia of extraction was visualized with and through the larger media infrastructure of BP shaped by an assemblage of film units, print publications, and staff photographers who worked for oil and also consumed oil; not only as a material commodity but also as an image of modernity.

The BP Archives housed at the University of Warwick’s Modern Record Center now holds the remaining film and photography production of BP throughout the 20th century, serving as a portal to the infrastructural, social, and political development of Anglo-Persian Oil Company which only in 1954 was renamed and rebranded as British Petroleum, a historical fact unknown to the general public (Fig.5). BP Archives has become the official source for historical storytelling – one whose compromised images offer a seemingly documentarian outlook toward the company’s past.

The film and photography practices of BP were crucial in narrativizing the exploitative economic exchange between the central government of Iran, the oil company, and the British government by extension. In 1937, the company produced a film titled “Dawn in the East: Story of Modern Iran” as a gesture of good-will to the despotic monarch Reza Pahlavi. It portrayed Iran’s growing infrastructural modernity and ancient cultural riches, as opposed to the oil company’s usual representation of the dire living conditions in rural Iran.

“Dawn in the East: Story of Modern Iran” is clearly a propaganda film; but many such films are resurfacing as clips on social media platforms and YouTube as nostalgic glimpses into Iran’s burgeoning modernization, valorizing the Pahlavi era as Iran’s hopeful and lost past. A similar case can be said about the film “Persian Story” whose clips of Abadan’s swimming pools and cinemas often resurface and are shared online in personal blog posts or social media platforms glorifying the nostalgia of the past. The filming of Persian Story was done in 1951 during the height of labour protests and the oil nationalization movement. But the film was publicly released and screened in different festivals across Europe in 1953, which completely concealed the social and political turmoil caused by the oil company at the time (Fig.6). The film’s homogenizing and authoritative gaze from above seemingly unites the oil town of Abadan as a single and concentrated unit of production wherein the social spaces of leisure–although in reality highly segregated based on the rank within the company and ethnicity–are depicted as one of the main contours of measuring the productive time in the oil town.

Perhaps one reason that the afterlife of these “petro-films,” a term aptly proposed by media scholar Mona Damluji, becomes imbued with nostalgia is their original visual grammar and mode of representation which alienates the viewers from seeing the social realities of living in oil towns and replaces those with industrial realist portrayals. These cinematic portrayals are deprived of any embodied point of view and silence the subaltern voices whose livelihoods were deeply affected by the violence of the oil company. The image regime that corroborated with the labour regime of the oil company firmly guarded who enters the historical record of the company and in what visual registers.

Another interesting case is the film “Anglo-Iranian Oil Company Operations in Iran” which became the first publicly known film produced by the oil company in Iran. Initially completed in 1921, it was only shown to company officials. Later, however, the film was updated with additional title cards and was re-edited for public viewership. However, based on the film records at the British Petroleum Archives, an earlier film was shot in 1920 but never publicly shown. A small side note in a chronology of BP’s films made in Iran mentions a seemingly small but important detail about this “unseen” film: “Owing to the fact that it [the film] showed a lot of unsuitable subjects, such as the huge percentage of Indian labourers, etc., etc., [the film] was never displayed publicly.” This minute detail from the film department points to the invisible presences of thousands of migrant workers from the Indian subcontinent who formed the scaffolding of the industrial oil complex in Iran during the onset of the 20th century.

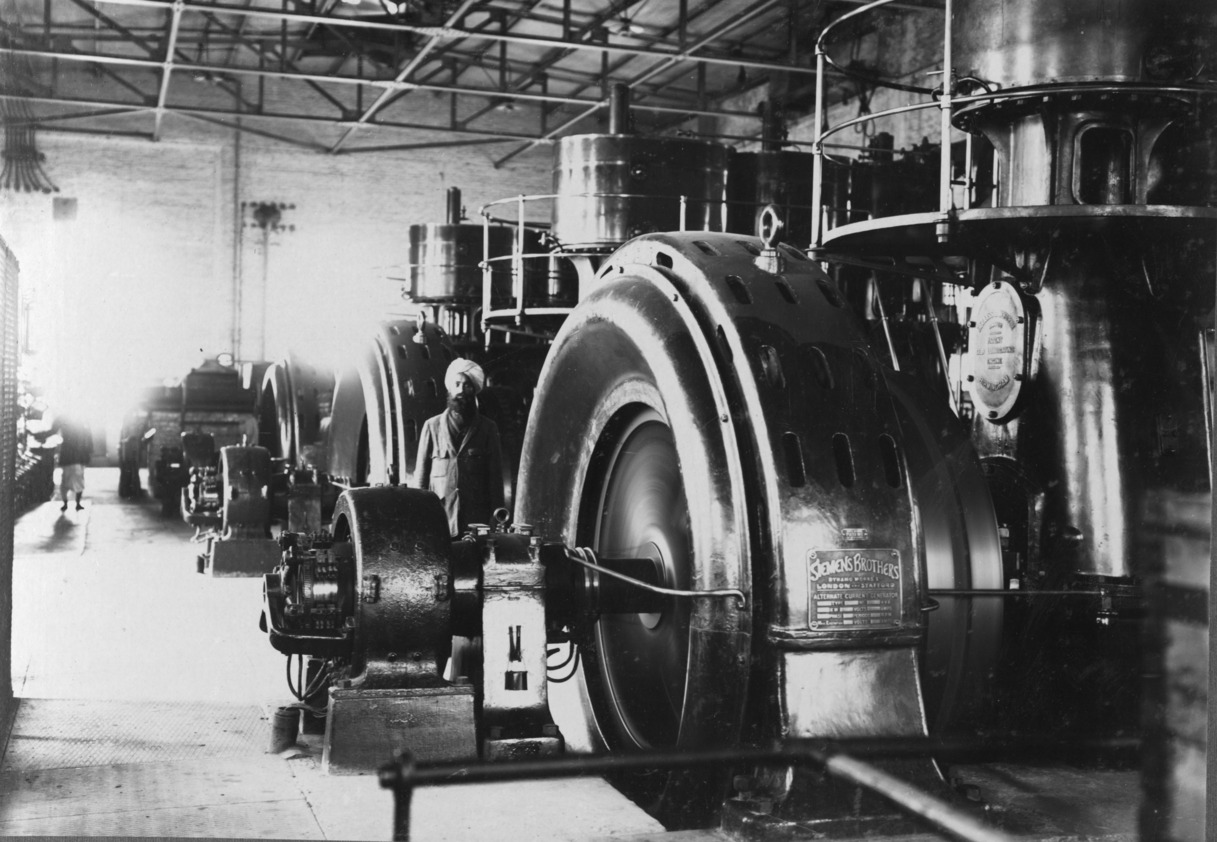

The visual history of South Asian migrant workers in Iran has remained invisible mainly due to the fact that BP’s official account of its operations systematically hindered the inclusion of a large section of its subaltern labor force from entering its official visual record both in its photography and film production (Fig.7). The ongoing fight between the central government of Iran and the oil company officials over “Persianization” of the workforce and training Iranian workers for technical jobs was the main reason behind the oil company’s strategic exclusion of the large South Asian population working in Iran from its visual records in the archives. It is through this archival regime that BP has managed to popularize its false historical image. British Petroleum’s archival regime stands for an authorized institution, guarded space, colonial technology and practice, as well as its visual grammars of extraction which have historically operated through eradication. How can the BP archives be reliable historical narrators when they are so out of sync with the lived experiences of extraction? Furthermore, how can we read the archive against its own grain?

In the process of seeing the history of oil in Iran, the horror resides on the edges of the frame, in the encounter with those inhabiting the images of extraction for over a century. Throughout my archival field work, I became drawn to using the magnifying glass to see whether I could find any bodies in the shadows of industrial buildings, camouflaged by large machineries and alienated by the external documentarian frame of the images (Fig.8). A search to encounter and magnify the eerie instances when flesh became one with infrastructure. I became drawn to the shadows of infrastructure, because almost always, I was able to see the outline of an oil worker seeping through its colossal physical structure.

Images of oil in the BP Archives consist of a foreground and a background. Those inhabiting the shadow economy of extraction in the background were also coded through racial difference and dispossessed of the wealth generated by the same machinery of oil (Fig.9). If we think of the archives as the commons and not the past, as Ariella Azoulay argues, we are then able to read through these shadows, absences, and shared struggles and not assume the archive as merely a source for historical facts. Unearthing the disembodied social experiences of extraction and its unseen labour from the seemingly embodied camera of the oil company requires a different archival optics.

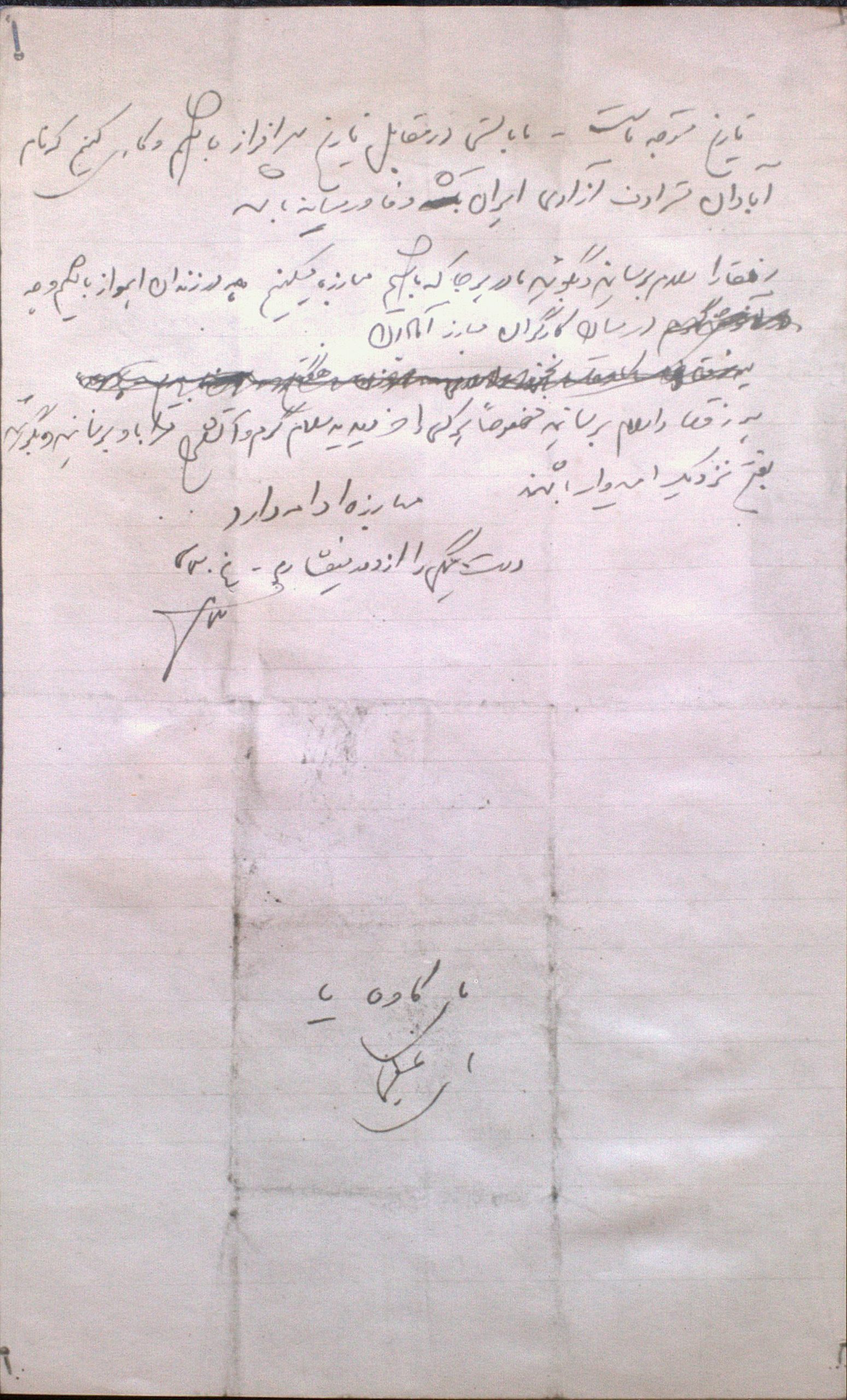

There is a space in which still images can move and transplant the reader and become a portal to an elsewhere and an elsewhen. Collective fingerprints from oil workers on strike, letters written by labour activists from prison declaring their political demands with great awareness of their historical role in shaping the nationalization movement not only in Iran but the broader West Asia (Fig.10), secret anticolonial pamphlets to be distributed across the oil towns, all amount to acts of refusals and solidarity hiding in plain sight in the archives.

Are these acts of solidarity and refusal our collective commons to be reminded of as we wrestle to redefine and recapture our modes of identification and negotiation with the troubled history of the oil industry in Iran?

Southwestern oiltowns and oilfields of Iran at the disposal of the British empire became the testing grounds for the technical cusp of the transition from coal to crude oil at the onset of the 20th century. But they also became an active site for political resistance with a growing labour consciousness which inspired many social and political movements across the region. The petro-utopias of Iran became the laboratory to calculate how the global energy complex could operate its planetary regimes of extraction at the expense of the subaltern labour force. But they were also a political laboratory of resistance.

Our task now is to approach the archive as a battleground wherein we have to construct through the absences and retrieve the voices of its workers from the shadow of extraction. To continue in the path that the oil workers, our companions in the archives, started over a century ago and to see far beyond the nostalgic images of petro-utopias. Archive is a verb: it sees and it silences. Now more than ever, we need to start by weaving and reading through these silences in the archives. As one of the oil workers from the prison once wrote: “The struggle continues.”

2 comments

thanks for this great article! is there a reason you didnt include the bakhtiari -on whose land middle east oil was first found?

http://www.bakhtiarifamily.com/oil.php

after i walked kuch with the faridgi family, some of my photos were shown i n the brunei gallery at soas and, in what was then the main soas building, i did a complementary exhibition of images of the baktiairi including a whole section on oil including some from the bp archive.

https://carolinemawer.com/bakhtiari-2/

mine was the first brunei exhibition to have a website section – i insisted on it as i didnt want to lose the voices of the bakhtiari (id been working with Khans in London and elsewhere).

its now deleted – but maybe you too might consider not losing the very earliest iranian oil workers – negotiating with the british extractivists / ‘guarding’ the first oil sites / living on the land that the first pipes went across

of course that wasnt ever a utopia and it all got much worse for the bakhtiari leaders: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4311723

best wishes

What a very interesting piece of considerable work. I will study it in more detail. Might I just mention that as Master of St George Abadan Lodge No.6058 that our lodge was consecrated in 1939 in Ababad having been formed by BP Oil Workers. It subsequently, along with other Gulf Lodges relocated to the UK. As far as I am aware only two remain. Ours which meets at Chatham and St George Bahrain which meets in Ashford. Much work has been dome by one of our members to return the ceremonial ritual which we use to that which was used in Abadan as a tribute to our Founders. We would love to hear from other BP stuff who are Freemasons or indeed any who would like to join. Kind regards, Robyn Murdo-Smith. Tel: 0782 522 5236