A post written by Asher Kohn, a law student at the Washington University in St. Louis, focusing on the interplay between theories of jurisprudence and land use in Central Asia. Follow Asher on Twitter @AJKhn. For other articles in Ajam’s series on Armenian-Iranians, check out “A Bridge to New Julfa: A Historical Look at the Armenian-Iranian Community of Isfahan” here and “The Bridge to New Julfa: The Golden Age of Isfahani Armenians” here.

Tehran has grown rapidly in the past four decades, subsuming disparate neighborhoods into a (moderately) coherent whole. The Vanak neighborhood of central Tehran holds a fascinating index of place names, as if the urban planner picked them out of his historian older sister’s bookshelf. Vanak Square itself lies at the intersection of Haqqani and Gandhi, hemmed in by boulevards Africa and Brazil. I imagine myself driving a stalwart Samand, taking the Kordestan Highway north and passing the Sheikh Baha’i Shopping Center on the left and the Motahhari Hospital on the right.

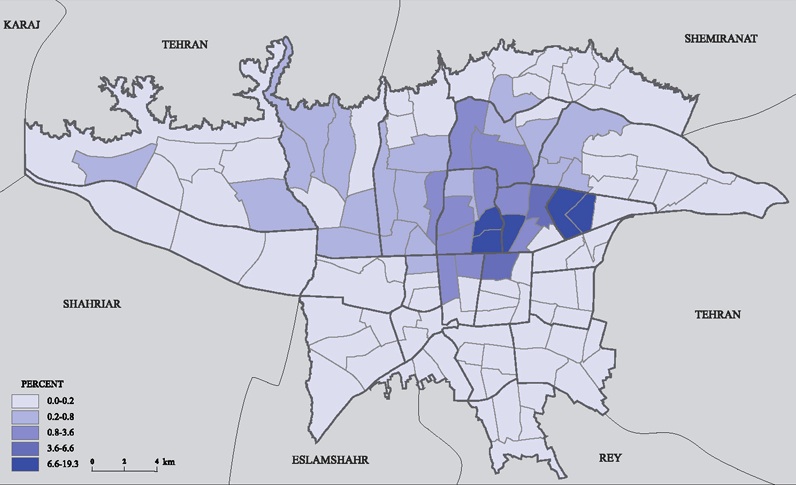

Straight ahead, rapidly dominating my field of vision is the Ararat Armenian Sports Club. Vanak is home to a high concentration of Armenians; half of the approximately 800,000 Armenians in Iran live in Tehran, and most of those Tehrani Armenians live within Vanak and its orbit.

Of course, these toponyms were not taken from the aether but rather from a very practical need to rename most things in a city (and needless to say, a country) dominated by the Shah. After the Revolution, all names related to the Shah in a city dominated by royal imagery were changed to represent the new government’s aspirations. Pahlavi Street became Valiasr Street and Shahyad Aryamehr (King Memorial Tower) became Borj-e Azad (Freedom Tower). But Armenian toponyms needed no such rebranding. The Ararat Armenian Sports Club predates the Revolution and predates Reza Shah Pahlavi. And though its current incarnation is boxy and mid-century generic, nestled within the complex is a delicately balanced grey structure whose thin verticals belie its concrete mass.

One of the finest examples of Iranian architecture in the neighborhood is an Armenian chapel, Surp Khatch. It’s not quite hidden from view; nothing could be in the traffic-choked metropolis. But the modesty of the building’s size is certainly no match for its more grandiose architectural ambitions.

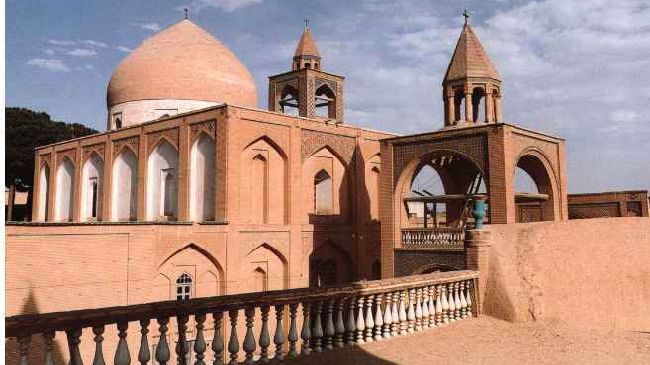

Surp Khatch Chapel holds a peculiar significance within Armenian-Iranian life. There are dozens of Armenian churches within Iran, mostly in Tehran and the western provinces. Vank in New Julfa deserves special recognition, of course, for its role as the heart of the Isfahani community, brought to Persia by Shah Abbas I in the 17th century.

The Prelacy – the bureaucratic head of the Armenian Church in Iran – makes its home in Saint Sarkis, a church that dates back to 1970.

These Armenian churches – and most others in Iran – look like Armenian churches; a central tower and an equal-armed plan dominate the structure, and one in New York is similar in thought, if not upkeep, as its counterpart on the plains of Ani.

When the Armenian-Iranian community celebrates their brother Armenian Republic’s 21st birthday, they do it at Surp Khatch. The Armenian Apostolic Church is an essential part of Armenian life no matter what color the passport. The brutalist/modernist lines of Surp Khatch and its location at the Ararat Armenian Sports Club suggest that it represents a localized heritage in the minds of its Armenian-Iranian flock.

If all Armenian churches look similar, than they must also look staid. This is perhaps part intention and part obvious fact; many are quite old, and those that are not are made to appear as such in order to reference the glorious past. Surp Khatch, built in 1987, takes influences perhaps from the Maqbaratoshoara, a mausoleum for poets in Tabriz, and from Armenian Genocide memorials; unflinching concrete that both memorializes and yearns for a hopeful future. If this is indeed the inspiration, it is in the right place.

As mentioned previously, Surp Khatch is on the grounds of the Ararat Armenian Sports Club. The Sports Club is home to FC Ararat Tehran, a borderline-defunct soccer club that produced two heroes of Iranians, Armenians, and of course Armenian-Iranians. Andranik Eskandarian played for two years at Ararat before moving onto Taj (now Esteghlal due to yet another Revolution-necessitated makeover) as a stalwart defender. His national teams won the 1968, ‘72, and ‘76 and went to the country’s first World Cup in 1978. Andranik would later move to the United States to play for a legendary New York Cosmos side. A generation later, Andranik Teymourian would play youth ball for Ararat before moving on to Bolton in the English Premier League and one of the most iconic images from the 2006 World Cup:

Soccer is often used as synecdoche for a country’s larger ills and woes, and rarely satisfactorily. What soccer can do instead is provide a secular window into the culture of a community. The Armenian Church and Hayeren (the Armenian Language) are central in maintaining and preserving Armenian identity and culture. Sports and sports leagues are modern and secular accompaniments to what has historically been a primarily religiously-based community.

Sport is a venue that gives its participants the opportunity to negotiate their identities without having to explicitly address loaded issues of confessionalism or mother tongue. Someone like Teymourian can be a hero for Iranians of all religions without a hint of conflict. There is no need for equivocation when wearing the national kit with “TEYMOURIAN 14” on the back, no matter if the bearer of such sartorial pride is named Hovhannes or Hossein.

Surp Khatch is an undeniably Christian building, constructed as it is with interconnected crosses. And yet its concrete facades point towards modernity and a connection to the urban fabric, not the diffidence of most purpose-built religious structures. This modernist style can be seen throughout Tehran, most particularly in the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, and as a result Surp Khatch’s concrete idiom is perfectly at home in the concrete jungle of Downtown Tehran.

Armenian-Iranian architecture, particularly Surp Khatch, fits comfortably within the Iranian modernist idiom. The situation of Armenians (and other Christians) in Iran is of course far more normal than prevailing Western discourse may have an outside observer understand. Armenians have different treatment from most Iranians, with special privileges to pork, alcohol, and Sundays off work that Muslims do not enjoy. But they are still effusively Iranian. Surp Khatch, for example, was built in part to memorialize the thousands of Armenian service members killed in the Iran-Iraq War. When Teymourian crosses himself before a match, his countrymen cheer this act as the mark of a pious Iranian.

The negotiating of political space for religious minorities in an explicitly Islamic Republic is an ongoing political issue that is going strong on its fourth decade. But political concerns hardly frame daily life; Armenians and other religious minorities in Iran generally name their primary concerns as drug use and a rapidly deteriorating economy. The communities’ problems aren’t necessarily their status as minorities, but the general problems that stem from being Iranian. Indeed, minorities in Iran are well-integrated not only socially and culturally but politically as well. There are five Armenians in Parliament (compared to four Assyrian and Chaldean Christians, three Jews, and two Zoroastrians in the 290-seat Majlis). There are also Armenian observers to the Expediency Council and the Guardian Council. Surp Khatch is but a part of the Iranian social fabric and only a single aspect of the complex fabric of the Armenian-Iranian presence.

Unfortunately, these days Ararat FC is far from its glory days. The team last competed in Iran’s top league in the 1995-1996 season. The Sports Complex itself is kept alive and thriving however, primarily due to remittances from abroad that are exempt from the omnipresent sanctions on Iran. Surp Khatch remains standing through remittances as well, although one looks at the concrete and thinks obstinance can overcome what an exponentially-dwindling rial cannot. And perhaps that is what the spindly concrete is there to represent.

The chapel is just a small and peculiar outcropping of faith, meant to capture interest and give either a quiet respite from the continuous traffic or a meeting place for the community, however defined. But it is a distinctly Tehrani place, a concrete ornamentation of the urban fabric and not a stone cross-and-cylinder break from its surroundings. The building is small. It is peculiar, sure, but undeniably Armenian and inevitably Iranian, just like its community. And with its concrete frame and cruciform ornamentation, it demands to stand just as long as them, too.

–

For more pictures of Surp Khatch Chapel, check out:

Hayaxk: Surp Khatch Chapel – Ararat Stadium Tehran

all photographs courtesy of their respective owners and can be clicked through to their original source.

12 comments

Very nice article. Even though I get the point that the main concern of many minorities are the same socio-economic issues that other Iranians have, I think the statement that “minorities in Iran are well-integrated not only socially and culturally but politically as well” is highly simplistic. The author should try and look at less privileged and non-urban minorities in Iran’s peripheries, and ask them if they agree with that statement.

That’s a valid point when speaking about Iran as a whole. I think in this case though the author’s statements are explicitly directed more to the position of religious minorities, who tend to be by and large well-integrated (into both the good and the bad!). The historical concentration of Armenian, Jewish, Zoroastrian, and other Persian-speaking religious minority communities in urban areas has led to a unique political, economic, and cultural situation vis-a-vis the Persian Muslim majority. This situation makes comparisons between-on one side- Persian-speaking religious minorities- and on the other side- ethnic or linguistic minorities- quite difficult, given the extremely different historical locations & geographies of these groups.

Also important to point out, I think, is that being “well-integrated” in this sense doesn’t necessarily mean that things are great, but more so that a group imagines itself and is imagined as Iranian and as an integral part of Iran…

Thank you. I think your third sentence about me being “highly simplistic” is true. You and I could both go through Ajam’s archives alone to find numerous examples of less privileged and non-urban minorities. I was generalizing to contextualize the Armenians in Tehran. If you gave me 3,000 more words I would write more nuance, but at some point you could grow tired of me.

An earlier editor took the same exception and said “So Armenians lives don’t suck from being Armenian, they suck from being Iranian?” and I think that sums it up. Armenians in Tehran have the same daily struggles most Tehranis do. I know about other instances and other contexts, but I just chose not to write about them this time. I will hopefully get around to it though, thank you for the comment.

Reblogged this on messerwerferin.

Thanks for writing this. Very glad to read about our Matour (Chapel) in here. The name of the architect who built Sourb Khach chapel is Rostom Voskanian. An Ararat member who contributed greatly to Iranian modern architecture.