Part III of III in a series on Slavs and Tatars‘ Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz– a multiplatform exhibition, lecture-performance, and publication looking at the unlikely shared story of Poland and Iran. The exhibition opened at REDCAT gallery at the Roy and Edna Disney Theater/Cal Arts in Los Angeles on February 9th and runs through March 24th, 2013 and is now showing at Vancouver’s Presentation House from April 13th to May 26th, 2013. For more from Slavs and Tatars, check out “Polish Shi’ite Showbiz: Slavs and Tatars on Solidarność & the ’79 Revolution” and “Crafts as Citizen Diplomacy: Slavs and Tatars on Revolutionary Media in Iran and Poland.”

Recently, Ajam’s editorial staff had the pleasure of sitting down with Slavs and Tatars to discuss their work, which melds history, geography, folk culture into provocative art and performance.

Slavs and Tatars is an artist collective that works to highlight historical connections and regional linkages often overlooked due to rigid geographic boundaries. Founded six years ago, their work focuses on Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Middle East, or the broad cultural continent they term “Eurasia.” This work introduces audiences to cultural exchanges between seemingly unlikely places, reminding us of the interconnected nature of global culture and highlighting histories often obscured by the rigid workings of modern geopolitics. Their commitment to an accessible, yet meaningful, art offers a refreshing dialogue for people willing to reconsider the “separateness” of the terrains of “Central Asia,” “the Middle East” and “Eastern Europe” as much more connected than otherwise expected.

Slavs and Tatars offers a unique reading and deconstruction of monolithic notions of history, revealing a today very much rooted in yesterday. As a history student, I’ve followed their work for years, always pleased and surprised by their ability to initiate conversations through its pieces, which they continually expand on either in their books (PDFS available for download on their website!) or public lectures and talks available to both academic and art world audiences. The accessibility of the work goes beyond free downloads, present even in their actual media: by producing visual, audial, and literary works, they cater to different types of learners and consumers of knowledge.

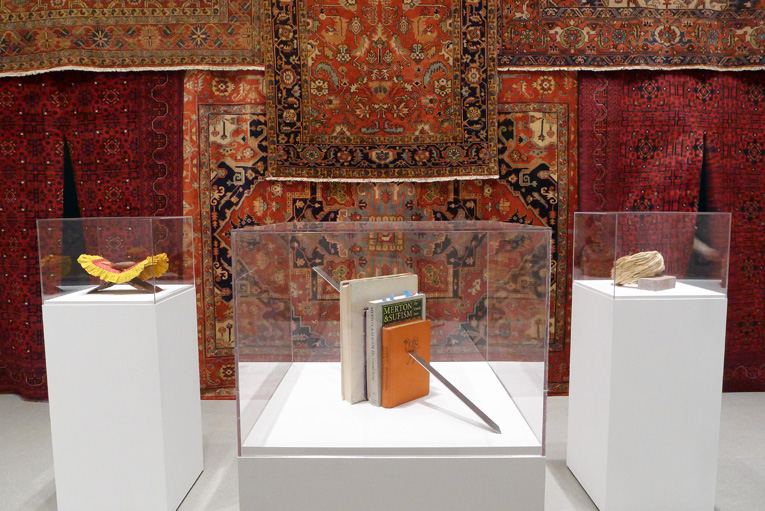

Slavs and Tatars’ kitab-kebab is one example of the depth of their work. The piece, which spears six books together on a kufta-kebab skewer, explores the materiality of the book in addition to the textual information embedded in it. By skewering these books together, Slavs and Tatars questions how information is traditionally processed and categorized: should knowledge be processed horizontally, dabbling in different fields, or vertically, with an intense focus on one particular subject? Instead of buying into this binary, Slavs and Tatars provides an alternative, encouraging their audience to have a corporal and critical relationship with knowledge production.

In fact, Slavs and Tatars started out as a sort of book club, which served as inspirations for their many installations. Perhaps that is what makes Slavs and Tatars such a revolutionary art collective. Even today, they stress that their work seeks to draw the audience to their books, offering an unconventional approach whereby the pieces exhibited refer back to the books being written and produced by the collective. At their core, Slavs and Tatars initiated a sort of intellectual enterprise, creating pieces intended to draw audiences into much bigger and deeper conversations than those found traditionally within art. Their approach collapses art into itself, where sculptures, say, become more than something to be seen, but rather, something to be contemplated.

Listen to Slavs and Tatars on the Book [ca_audio url=”http://ajammc.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/S_T-the-book.mp3″ width=”750″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

In a world full of heavy-handed visual depictions of current political or social issues that rely on simplistic, reductionist constructions of culture, Slavs and Tatars offers work rooted in a nuance and more subtle understanding of history.

Arbitrary regional boundaries and reductionist labels define academic departments and museum wings everywhere. “Middle Eastern Studies” and “Slavic Studies” departments grace almost every American university campus, and museums are often divided into “Islamic Art,” “Russian Art” and so on and so forth. These divisions hail from imperialistic and Orientalist modes of knowledge, alienating peoples from their neighbors and defining them through their relations with Western Europe. Such contemporary categorizations are remnants of this way of thinking.

Slavs and Tatars not only work in between these institutions, but in fact, succeed in critiquing them for being short-sighted in their worldview and existence. For example, their latest exhibit, “Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz” (which they wrote about for Ajam here and here) could not be categorized in either of these departments, as the pieces speak equally to Poland as they do to Iran. Friendship of Nations is, at heart, a project of critical geography, a theme that weaves through much of Slavs and Tatars’ work.

Nor could their work be housed in discipline-based departments, such as history or art history, because their multi-faceted installations and writings transcend any one discipline. Slavs and Tatars draw on multiple inspirations and methodologies, different material for an equally diverse audiences. Instead of operating in one distinct mode, Slavs and Tatars have created a place for their work, a homeland, so to speak, which welcomes transversality and storytelling across cultures.

Even if a museum had an appropriate section to display Slavs and Tatars’ works, the very essence of a museum as a cold and stark gallery for art to be placed on the wall is uninviting, an issue which they actively address in their approach to create an interactive experience. Slavs and Tatars incorporate the physical architecture of the gallery as a part of their presentation, and the souk-like atmosphere of their installations with benches and rugs provides a new space for viewers to absorb their surroundings without having to shuffle from one piece to another. Their recent exhibition, Beyonsense, offered a counterpoint to the MoMA’s approach to artistic modernity by creating a psychedelic reading room, warm, textured, and collective as opposed to rational individualism of steel and glass. By further engaging audiences at lectures or discussions at exhibit openings, Slavs and Tatars push audiences to contemplate and engage their work on a deeper level than walking by a series of framed pictures on the wall.

Listen to Slavs and Tatars on Museum Space [ca_audio url=”http://ajammc.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/S_T-museums-cold.mp3″ width=”750″ height=”27″ css_class=”codeart-google-mp3-player”]

Of course, their unorthodox ways of conceptualizing historic and cultural relationships have been met with different reactions from their international audiences. With exhibits across Europe, Asia, and North America, Slavs and Tatars have met with a variety of peoples.

Many audiences of various stripes have a kneejerk reaction to projects that deconstruct monolithic notions of history and culture. Even as many appreciate the work, some Iranians, for example, might take offense at projects that lump them in with broader Eurasia or that seem to imply a more culturally mixed past than nationalist narratives of history allow. This reaction is repeated among different nationalities, pointing to the continuing strength of narrow nationalisms in defining contemporary identities around the world.

The diverse tapestry of modern Iranian history, imbued as it is by a rich mix of Islamic symbology and Persianate art, plays a major role in Slavs and Tatars’ work. Because their work is invested in the modern rather than in romantic notions of antiquity, Slavs and Tatars highlight a different kind of “Iranianness” that many Iranians tend to overlook or ignore. For example, the 1979 revolution one that many diaspora Iranians claim in different ways, and some don’t claim at all. These differing views color many audiences’ reactions to their exhibits: Iranians in the UAE have been much more responsive to their work, for example, than Iranians in the United States, reflecting the varied histories of these two strands of the Iranian diaspora.

Iranians in the States tend to favor a modern, urban, secular, and bourgeois understanding of culture, views which repel them from depictions of “folk” or “popular” culture. Poles, on the other hand, are generally proud of the revolutionary movement of 1989 depicted in the works, and as a result, have largely responded positively to Slavs and Tatars’ exhibits and installations.

Slavs and Tatar’s work, however, rejects superficial binaries of “Iran” and “the West,” which are deeply rooted in Orientalist understandings of geo-politics. Instead of splitting the world into political spheres of influences, Slavs and Tatars have taken on the role of a storyteller, using one story to tell another. Using 1979 and 1989 as key points to tell the stories of revolution and protest in Iran and Poland, Slavs and Tatars enrich these histories by linking them to each other. Isolated incidents tell us little about history until we consider them in a greater context.

Their contributions, however, are not limited to the art world. Academia stands to be critiqued and revamped as well, and Slavs and Tatars’ is constantly looking for ways to create cross-cultural and disciplinary exchanges between universities around the world.

One idea is to have a mathematics department (MIT, are you interested?) invite a specialist of sacred geometry, found in mirror mosaics, from the Middle East as a guest lecturer for the year. Middle Eastern (and Islamic) mosaics, governed by mathematical laws, provide an unexpected and creative application of a practical discipline.

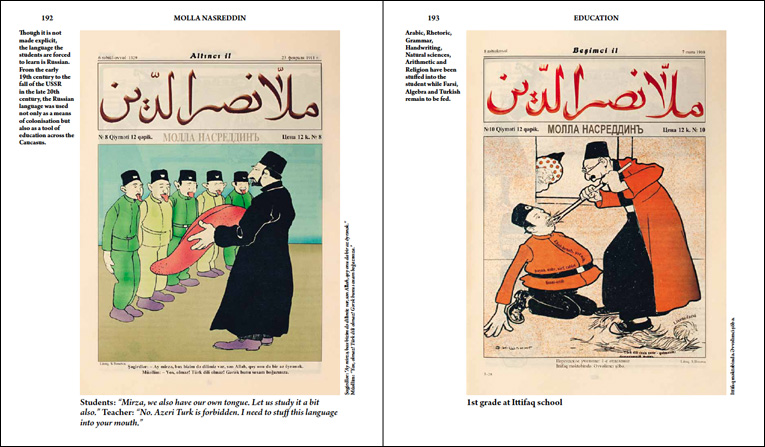

Another idea is creating the “Molla Nasreddin Chair of Economics,” perhaps at a fine institution like the University of Chicago. Molla Nasreddin, who is the blundering protagonist of short stories, could serve as a character to point out the pitfalls of an overly-analyzed system like economics. Both these ideas turn the departments on their heads, inverting them while still speaking to the philosophy of the institutions. The deconstruction of disciplinary and geographic walls built around academic departments signifies the thoughtfulness in Slavs and Tatars’ works.

A “think-tank without the agenda,” Slavs and Tatars have achieved challenging many preconceived notions and introducing little known concepts and connections to a larger audience. From language to politics to religion, Slavs and Tatars’ commentaries run deep through their work, contributing to a much-needed discourse on the land between Slavs and the Tatars with humor and depth.

3 comments

Beeta, could you write a post about white slavery from the Caucasaus and Russia? White slavery is typically overlooked and erased due to racist thinking from white academia. Iranian historiography repeats this pattern. European Imperialsim and White American history have made slavery associated with black people and this has affected how other countries write about slavery, including Iran.

You included a link about slaves from Southern Russia and the Caucasus on your post on Afro Iranians, but that’s not enough. I think a whole post dedicated to white slavery would be educational and reinforce the fact that slaves in Iran were not just African descent. And if you do choose to write this post, I think it would be fascinating where these desendances of white slaves are in Iranian society. It’s not a coincidence that many Iranians look European.

It’s very interesting information. Thank you very much.

Perhaps you know, that an outstanding Tatar historian-scientist D. Iskhakov wrote in 2000: “the real history of Tatars, of the people in every respect historical, is not written yet”.

However, recently were published books about the unwritten (hidden) real history of Tatars, written by independent Tatar Historian Galy Yenikeyev.

There are a lot of previously little-known historical facts, as well as 16 maps and illustrations in this book.

This book presents a new, or rather “well-forgotten old” information about the true history of the Tatars and other Turkic peoples.

It must be said, that there are many pro-Chinese and Persian falsifications of the “wild nomads” etc. in the official history.

Therefore, primarily we should know the truth about the meaning of the names “Mongol” and “Tatar” (“Tartar”) in the medieval Eurasia:

the name “Mongol” until the 17th-18th centuries meant belonging to a political community, and was not the ethnic name. While “the name “Tatar” was “the name of the native ethnos (nation) of Genghis Khan …” , “…Genghis Khan and his people did not speak the language, which we now call the “Mongolian”…” (Russian academic-orientalist V.P.Vasiliev, 19th century). This is also confirmed by many other little known facts.

So in fact Genghis Khan was a Tatar and a great leader of the all Turkic peoples. But with time many of his descendants and tribesmen became spiritually disabled and forgot him and his invaluable doctrine and covenants… Tatars of Genghis Khan -medieval Tatars – were one of the Turkic nations, whose descendants now live in many of the fraternal Turkic peoples of Eurasia – among the Tatars, Kazakhs, Bashkirs, Uighurs, and many others.

And few people know that the ethnos of medieval Tatars, which stopped the expansion of the Persians and the Chinese to the West of the World in Medieval centuries, is still alive. Despite the politicians of the tsars Romanovs and Bolsheviks dictators had divided and scattered this ethnos to different nations…

About everything above mentioned and a lot of the true history of the Tatars and other fraternal Turkic peoples, which was hidden from us, had been written, in detail and proved, in the book “Forgotten Heritage of Tatars” (by Galy Yenikeyev).

There are a lot of previously little-known historical facts, as well as 16 maps and illustrations in this book.

On the cover of this book you can see the true appearance of Genghis Khan. It is his lifetime portrait. Notes to the portrait from the book says: “…In the ancient Tatar historical source «About the clan of Genghis-Khan» the author gives the words of the mother of Genghis-Khan: «My son Genghis looks like this: he has a golden bushy beard, he wears a white fur coat and rides on a white horse» [34, p. 14]. As we can see, the portrait of an unknown medieval artist in many ways corresponds to the words of the mother of the Hero, which have come down to us in this ancient Tatar story. Therefore, this portrait, which corresponds to the information of the Tatar source and to data from other sources, we believe, the most reliably transmits the appearance of Genghis-Khan…”.

This e-book you can easily find in the Internet, on Smashwords company website: https://www.smashwords.com/profile/view/MIG17