In the lead up to the 2010 US National Census, campaigns emerged across the country calling for Iranian-Americans to stand up and be counted. One of the most memorable of these was “Check it right, you ain’t white,” a movement that targeted Arab- and Iranian-Americans, urging them to write in their ethnic identification instead of checking the box for “White,” as forms generally ask those of “Middle Eastern” descent to do.

Awkwardly, the campaign somehow backfired, and the number of Iranian-Americans who wrote in “Iranian,” “Persian,” or “Iranian-American” in the census was 289,465, significantly less than 10 years before. Given that unofficial estimates of the current Iranian-American population run between 1 and 1.5 million, the vast majority of Iranians probably identified themselves as “White,” or else didn’t bother turning their forms in.

The Iranian-American voting campaigns of 2010 US Census speak volumes about the complexities of race and racial politics, not only in the Iranian-American community but also of Iranians more broadly. Iranians in Iran and elsewhere tend to identify with Whiteness as a result of the history of race formation and ethnicity politics back in Iran, particularly as developed under the Pahlavi regime until 1979. Those Iranians who immigrated to the United States in the late 1970s and onwards, meanwhile, have had this identification with Whiteness drilled into them as a result of the experiences of discrimination they have faced in this country since the 1979 Hostage Crisis.

And yet, identifying as White does not erase the problems of discrimination faced by generations of Iranians in the United States, and has instead merely led to a perplexing situation whereby Iranians are discriminated against based on their ethnic background but continue clinging to the myth of Whiteness with the desperate hope that claiming Whiteness will somehow save them.

The material success that many Iranians have enjoyed in this country, meanwhile, has obscured their connections with other discriminated groups, and instead fostered an attitude of “lay low, don’t make trouble,” that idealizes financial success as the key to realizing the American Dream. “We’re good Persians,” community leaders seem to say, not like those “Bad Iranians” over there that we all hate so much. Despite the racial discrimination Iranians regularly face as a community in the United States, many continue to insist upon their own Whiteness, refusing to even consider the question, “Are Iranians People of Color?”

Are Iranian-Americans People of Color?

“Person of Color” (POC) is a phrase that emerged out of political struggles against ethnic and racial discrimination in the United States, and exists in contrast to the identity “White” and the racial privileges that identity carries. POC explicitly recognizes the commonalities of experience shared by those who are not of the dominant racial group in this country, and expresses the need for solidarity among these groups in order to dismantle the existing system of racial privilege and hierarchy. Importantly, the term POC does not suggest that the experiences of all people of color are similar, but instead it recognizes the diversity of experiences of racial discrimination between groups. Using the term POC, however, insists upon the importance of recognizing the shared struggle of peoples of color for an equality and liberation that is predicated upon the equality and liberation of all.

As a light-skinned, biracial Iranian-American, however, the supposedly clear lines dividing White from POC are a bit difficult for me to parse. On one hand, I almost always pass as just White, and rarely if ever experience the feeling of being targeted, singled out, or discriminated against based on my looks alone. Despite increasingly bushy eyebrows, my light skin tone has long ensured that I enjoy substantial racial privilege for my ability to pass as (fully) White.

Passing as White meant I looked like “the norm” and was never made to feel out of place, saw people who looked like me whenever I turned on the television, and never had to fear or suspect that negative experiences I had were a result of racism (among many other privileges I enjoyed). I knew for certain that my father’s ability to pass as a well-tanned White man had ensured his own ability to succeed professionally at a time when his Iranian name had closed many doors. I was sure of this because his ability to pass, as well as my own, meant that we were both “privileged” to hear the secret racist and Islamophobic comments directed towards others that happened in the lily-white boardrooms and classrooms that we each navigated.

And yet the more I spoke with White folks about race, the more I began to understand that many of my experiences of bullying throughout childhood were directly tied to my ethnicity in ways I hadn’t previously realized. As obvious as it now sounds, it had never occurred to me before that being harassed for supposedly being a terrorist or being called “Saddam” or “Osama” in middle school hallways was not a universal experience for American children, and that these experiences were not merely unpleasant but were in fact definitively racist.

As an Iranian-American, my visits to see Grandma crossed “enemy” frontiers and bags thoroughly inspected by US customs officials to ensure I did not bring back too many pistachios, lest I incur a $250,000 fine for violating US sanctions on Iran. The desire to send back money to purchase Grandma’s medicine or help a cousin in dire financial straits had to always be weighed against the possibility of jail time in a US prison for engaging in financial transactions with the “enemy.”

US President Obama’s admission of the existence of a domestic spying apparatus far more widespread and pervasive than previously thought came as a major surprise to many Americans. Few of those surprised, however, were Middle Eastern Americans, for whom the announcement came as less of a shock and more of a “well, duh” kind of moment. After 9/11, elders whispered about being rounded up and put in concentration camps like the Japanese during World War II, and the childhood diary of my 11-year-old self merely noted at the time that things seemed to have gotten “worse.”

When thousands of men of Middle Eastern descent were called up for questioning a month after 9/11 and subsequently scheduled to be deported en masse, many of us breathed a collective sigh of relief that we still had some time to prepare before our turn came. Since the community has been on the receiving end of a great deal of attention from the various branches of the government’s spying apparatuses for years and especially since 9/11, the fact that the United States spies on its citizens and residents and suspends their constitutional rights for reasons they are not required to disclose had practically become common knowledge in Middle Eastern communities.

Although “flying while brown” (a riff on the classic, “driving while black”) has become an increasingly visible form of discrimination faced by Americans of Middle Eastern and Muslim backgrounds, few realize that other forms of targeting are extremely pervasive.

The first great wave of Iranian immigrants to the United States in the 1970s and 80s did little to prepare the next generation for the rise of anti-Iranian racism and Islamophobia in the years following 9/11. Many of this generation never quite got over the collective trauma of becoming “terrorist sympathizers” overnight following the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the Hostage Crisis. For over a year, Walter Cronkite ended every single segment of the CBS Evening News by telling Americans how many days had transpired since Iranians had taken the over the US Embassy in Tehran, reminding Iranians in the US on a nightly basis just how much the marker “Iranian” had become a liability.

And yet, many members of the generation of Iranian-Americans who experienced the wave of discrimination following 1979 continue to remain silent about their experiences. Some Iranians were beaten up on the street and called “sand niggers,” and “towel heads,” while others experienced the racism and xenophobia in more insidious ways, like discrimination in job hiring practices.

Even today, a 2008 survey indicated that nearly half of Iranian-Americans surveyed have experienced personally or personally know victims of discrimination due to country of origin. And through it all, community members by and large sought to keep their heads down and doggedly pursue the American dream, their lives collateral damage in a war between Iran and the United States that they had never asked to be a part of. It is difficult to bring up the memories of those years among Iranian families without provoking embittered silences and harsh rejoinders to not reopen the wounds of a fading nightmare.

The “Aryan Myth” and the History of Race Formation in Iran

One of the hardest aspects of discussion about racial discrimination against Iranian-Americans is how wound up in embarrassment and shame the whole topic is due to the history of racial discourse in Iran.

The specific form of nationalism formulated by the Pahlavi regime until 1979 insisted upon the racial superiority of the Iranian Persian people over their neighbors of all ethnic stripes. The regime aligned itself closely with the racialist White European superiority politics espoused by colonial empires, and generations of Iranians were taught to be pleased with themselves for occupying a low rung of the Aryan race ladder.

Although Iran is a multiethnic nation of Persians, Azeri Turks, Kurds, Baluchis, Arabs, Armenians, and many other groups, Iranians were taught to pride themselves for their Aryan blood and white skin and to look down on the supposedly “stupid” Turks and “backward” Arabs. As educated Iranians widely bought into this European system of racial hierarchy, Iranians began to see themselves as White in a global perspective and many carried this identification with them into the United States.

This narrative of race formation in Iran makes it extremely difficult for many Iranians to recognize themselves in the racist and Islamophobic discrimination they experience, often faulting Americans for being ignorant in ways that implicitly support racist and xenophobic targeting of non-Iranians.

This is probably best exemplified in the common assertion that Iranian-Americans should not be targeted because they are not Arab or because they are generally lax in their Islamic practice, and thus do not pose a “real” threat to Americans. The implicit argument, of course, is that Arabs and practicing Muslims should in fact be subject to surveillance and targeting because they do constitute a “real” threat.

“The Safe Kind of Brown”

Alas, informed discussions of race and racial privilege among Iranians and other Middle Eastern Americans often gloss over how histories of racial formation in our homeland as well as White passing privilege for many of us complicated attempts to subsume ourselves into the People of Color label. Many accounts of race politics and discrimination fail to recognize how for many Middle Eastern Americans, the ability to pass as White shields them from the forms of discrimination based on visible difference from Whites that are an integral part of daily life for many People of Color.

Although this passing privilege is by no means the rule for Middle Easterners in this country, it does inform the experiences of broad swathes of the various communities that fall under this umbrella. The experience of a dark-skinned, southern Iranian racialized by Americans as Black can hardly be compared to that of a light-skinned, green-eyed northern Iranian racialized by Americans as White.

These ambiguities and complexities are by no means limited to the Middle Eastern- or Iranian-American communities, but instead are an integral part of any identity politics based on a binary.

As Janani Balasubramanian brilliantly argues in relation to the South Asian Diaspora in the article, “I’m the Safe Kind of Brown,” the category Person of Color is not predicated on a uniformity of experience among those who take this label, and attempts to erase or ignore the differences among and between People of Color will without fail merely reify hierarchies of racial privilege and oppression that are much more complex than just national origin or visible markers of race or shade. As the author explains:

“Let’s stop buying into this narrative that our families all got here because we ‘worked hard and made it to the America’. Especially since those of us who came to the US in that first wave of professional South Asian (largely Indian) immigrants largely benefited from our caste and class positions in South Asia. Our families had access to the education and capital it took to enter those professional spheres.”

Similar arguments can be made for the Iranian-American community as well.

Solidarity is not predicated on sameness, but instead must be informed by an open and honest acknowledgement of difference. This difference must also include an understanding of how contextual all of these phrases are; in the United States, I may be a mixed Person of Color who passes as White, while in Iran I am a member of the dominant ethnic group and enjoy the privilege of American citizenship that sets me apart even further.

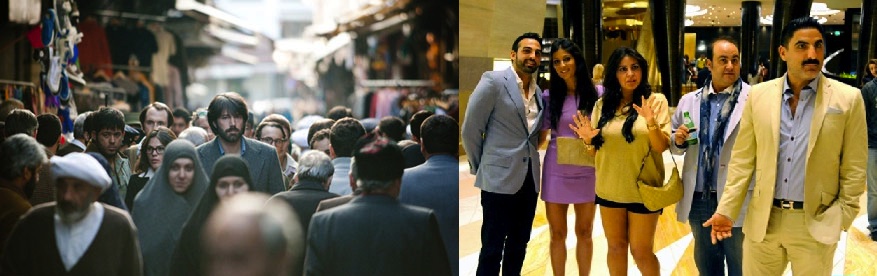

The complex legacies of race politics in the US and Iran as well as the very specific history of Iranian migration to the United States and discrimination against the Iranian-American community have combined to lead us directly into the model minority trap. While “Shahs of Sunset” and the “Persian palaces” of Beverly Hills are celebrated as emblems of Iranian success, the very real struggles faced by Iranians in this country are swept under the proverbial Persian carpet in an effort to give others and ourselves the most perfect, idealized image of Iranians possible.

When the only mainstream American television show starring Iranian-Americans depicts us as a bunch of rich idiots whose biggest goal in life is picking out the right plastic surgeon, we cringe a little but say to each other, “well, at least in this show we’re not terrorists.” Is this really how we measure our success and well-being as a community?

Identifying as White does not erase the problems of discrimination faced by generations of Iranians-Americans, nor does it aid in the struggle to dismantle the systems of oppression that structure US society as a whole. Iranian-Americans in this country today are a diverse lot and are confronted by a wide variety of pressing issues, ranging from legal status to poverty and religious discrimination. The issues of race and racial discrimination outlined in this article are but two lenses with which to understand and interpret the position of the Iranian community in the US today.

But the failure of Iranian-Americans to recognize their own complicated racial position in the United States risks doing our community a great disservice. We must be brutally honest with ourselves and with each other about systems of race and racial oppression in this country as well as how we fit into them, both in terms of privilege and oppression.

Only through this honest discussion can we begin to imagine more clearly how solidarities can emerge among Iranian-Americans and other communities of color in this country in the struggle to confront and dismantle institutionalized racism.

48 comments

wonderful article!

Very thoughtful and thought provoking article. Thankyou! I wonder if class could have been foregrounded a little more? If you had included images of North and South Tehran they would have been hugely different. Perhaps almost as different as your LA and ‘Iran’ pics? And I’ve never been to Tehrangeles, but are all Iranian-Americans in the upper echelons of boardrooms?

I doubt anyone even in our parents’ generation really identifies with this: “The material success that many Iranians have enjoyed in this country, meanwhile, has obscured their connections with other discriminated groups, and instead fostered an attitude of “lay low, don’t make trouble,” that idealizes financial success as the key to realizing the American Dream. “We’re good Persians,” community leaders seem to say, not like those “Bad Iranians” over there that we all hate so much.” What connections with other discriminated groups? There’s some specifically anti-Muslim prejudice, but the stuff during the hostage crisis compares better to the experience of German-Americans during WW1 than anything faced by black or Latino people in this country. In the older generation, people are often even more disdainful of the ‘bad Iranians’ than white Americans are, and not just for Americans’ sake. There are undeniable ways in which Iranians and Iranian-Americans suffer from white racism, but it seems like a stretch to say that this should lead to some natural solidarity among ‘oppressed people of color’. We are an extremely privileged, often not identifiably ‘brown’ ethnic group in this country, who have also faced at times serious discrimination and hostility. It seems important to recognize the specificity of that position, and how different it is from the position of groups with an extremely different economic position and history built around slavery, violent control, and illegal low-wage migrant labor. Given that, I don’t know why you would expect much more of Iranian-Americans than what you have, when it comes to politics or left politics: a small sliver of young people are led to radical or progressive positions for the same range of conscientious and narcissistic reasons that young white people are, with an added factor of bullying/discrimination/feeling of being out of place growing up, which is all too real but also very different and in most (though not all) respects more minor than that faced by other ‘people of color’ groups in the US. The risk of overemphasizing the extent to which Iranian-Americans are ‘people of color’ is to fall into a big-tent brown-people kind of outlook that neglects economic realities and their significance for realistic political strategy.

Thanks for your comments.

As I tried to point out in the article itself, it is hard to reduce “People of Color” to anyone thing, and solidarity can be built on recognition of difference, not just sameness. I think in your comments you seem to reduce being POC in the US to histories of “slavery, violent control, and illegal low-wage migrant labor,” and specifically refer to “what Blacks and Latinos experience” as the norm by which all experiences and oppressions should be judged (and potentially deemed inadequate, as you do in our case). What you’re describing is the experience of certain groups of People of Color, I agree completely- but it is hardly an accurate description of the experiences of all of the various racial minority groups in the United States.

Additionally, although class privilege and economic situation are deeply intertwined, they cannot be reduced to each other. Hence the fact that Indian-Americans or Iranian-Americans are wealthier than the median does not necessarily erase their racial positions, even if it might mitigate them, and might also create imperatives for these groups to identify strongly with Whiteness.

At the same time, Iranian-Americans are hardly a homogenous group. In 1979, a US imperial outpost was overthrown in a mass revolution, and large percentages of the Iranian elite and middle classes fled the chaos that followed. But at the same, hundreds of thousands of working folks, middle class people, low-level professionals, students, etc also fled, and the decades that followed the Revolution have brought an extremely diverse cross-section of Iranians to the United States. The narratives we hear and understand of Iranians are also deeply formed by those original elites, who had the most money to project their voices and opinions on arrival and to found community organizations and media. The opinions of our “parents’ generation,” that you refer to seems to be founded to some extent on those kinds of voices, but I can assure you, they are by no means hegemonic- just the loudest.

Ah yes, a “US imperial outpost”! It seems that our “leftish” Iranian comrades are still addicted to the sort of empty sloganeering and asinine ideologies that brought Khomeini to power and got hundreds of thousands of Iranians killed as a result (in that order).

آقای علی رضا، چرا این زبان درشت؟

منظورتان از leftish چیست؟

برادرم، وقتی ما در جایی که هستیم رنگی دیده می شویم و رنگیانه رفتار می شویم ، اینکه ما در ایران خودمان را چه رنگی می بینیم دیگر چه اهمیتی دارد؟ اصولن رنگی بودن و رنگی دیدن انسانها نا روا نیست ، این طبقه بندی کردن و برخورد با ایشان بر اساس رنگشان است که نارواست.

البته برتری رنگی بر رنگی دیگر را همیشه رنگ قدرت است که تعریف می کندو بی- قدرت همیشه همه چیز قدرت را زیبا می بیند و تلاشش را بر آن گذارد که خود را با معیار او آرایش کرده تا شاید در چشم او اندکی زیبا و آشنا آید. .

this comment is spot on, thank you

Great article!

I want to thank you for your article.

I’m Iranian-American [that is literally the first time I’ve ever typed that out]t, but I feel no connection with Iran and have never visited it nor have ever had the desire to go there. I was born and raised in America. My grandpas both were a part of the Shah’s government and were really close to him personally and his advisors, but when my parents came here in their teens, they started researching religion and decided to embrace living Islam. I was raised with a strong religious influence but never with an Iranian one.

Almost all of my relatives married someone white or in a few instances, other people of color. I have never had a single Iranian friend, although I’ve had a few acquaintances. I lived in Tehrangeles for a few years but almost any time I crossed paths with another Iranian, tried to pretend I wasn’t. I guess it’s also because of my headscarf and my assumptions of their immediate prejudices towards me. I guess due to all these factors, I’ve never felt a connection with identifying as “Iranian” and have actually run from this side of my identity.

I could pass as white but I have chosen to wear hijab, so I haven’t experienced white privilege very often. Although I will say that because I’m really outgoing and obviously don’t have an accent when speaking [lingual capital plays out in my life all the time], people have actually asked me on multiple occassions why I have my head covered. Not out of curiosity- not because they think I’m Muslim- but because they honestly thought I was European-American and were wondering why I was covering my hair.

I am really confused on what my ethnic origin is (middle eastern? because in theory I don’t know Iranians who would identify with that.) and avoid the topic completely, while fully recognizing I’m a self-loathing persian. Although, tbh, I don’t put all that much thought into it, except when I have to spell out to others my 13 lettered last name.

I am a strong advocate for social justice. I talk, write and teach about people of color and policies related to us and minority communities regularly and passionately. But I always do so in the framework of my association by religion, vs. ethnicity.

I don’t know why I’m writing this about myself. I think it’s because your article is the very first I have ever seen that talks about Iranians as people of color and it’s actually helped me process a part of myself. I know my post is jumbled and it’s because my thoughts still are. I’m actually ashamed to write much of this but I think it’s necessary for me to be honest with myself in order to grow.

Your article was actually was very comforting for me. I really thank you for it as I work to consider embracing my ethnic identity.

And also, it’s so, so rare to hear of an Iranian who has lived in Arab countries. I moved to Cairo to learn Arabic for a year [I’m now fluent in speaking, reading and writing Arabic, yet can only hold basic conversations in Farsi] and I would be told the same thing. My husband is Arab and the reaction of the few Iranians I know was: YOUR PARENTS ARE OKAY WITH THAT?!!! so sad.

Kudos to you. Please, keep writing.

Just wanted to give you kudos for your courage in sharing this reflection, especially as it’s clear you’re genuinely struggling with how to make sense of your personal experience and that is often difficult to do in public. Identity development is a journey – it might be that you’ve just arrived at a new crossroads/milestone. Best of luck as you struggle through – I think naming/claiming our truth is one of the greatest acts of resistance we can perform.

It’s november 18 2021 & all these years ur words were here expressing ur exp in life…i came across this website just now, never been to this site, liked the article, but ur comment was so honest, straight from ur heart, i hope u are well n happy with ur family. Idk if u consider sb like me as a fellow iranian now or not im a nobody but my heart goes out 4 u. U probabely will never read this reply but it’s my duty to tell u n anybody like u that we the ppl inside of iran love u

Pay a visit to iran n ur hometown plz, dont worry on the day 1 ask 4 Kalleh pache n the next day ask 4 Ab goosht then u’ll see how much of an iranian essence will explode out of u in shapes of slangs/looks/words as if bache nafe tehrooni lol

Kudos

There’s a lot of post-modernist jargon in this article. Moreover, it manages to get it precisely ass backwards. To the extent that they identify with a “color” racial category, Iranians in Iran usually identify themselves as “white” (sefid-poost). I have never heard an Iranian in Iran identify themselves as “brown” (the label “ghahvei-poost” does not even exist, as far as I am aware). At most, they would describe someone as being “sabzeh” (literally greenish, but equivalent to olive-skinned), but this is not used as a “color” racial category, as one thinks of white, black, etc. It’s a minority of “leftish” Iranians in the US and elsewhere in the West, at least in part influenced by the sort of post-modernist gibberish reflected in this article, who are desperate to became an official “victim” and “oppressed” class. The degree of socioeconomic discrimination faced by Iranian-Americans in the year in 2014 is infinitesimal (and I say this as an Iranian-American Democrat who grew up in L.A. and now works and resides in a very Republican state). I would finally add that traditional “formal” racial classifications have typically identified Middle Easterners as “white”, though everyday contemporary usage in US and Anglophone countries often does not.

There is no shame in being “white” unless you believe that “white” people possess a monopoly on moral turpitude or are responsible for most of the world’s misfortunes, which are nowadays very widespread attitudes among the “woke.” At the risk of being accused of “revisionism,” I’d like to propose that “white supremacy,” for all its myriad horrors (which many like to believe are the product of a “socially constructed” group that is somehow also genetically predisposed to such evil [cognitive dissonance!]), is relatively recent in vintage (and on the retreat given the ubiquity of self-loathing among people of European descent) and for most of the history of human civilization “olive” or “light brown” supremacy was the norm in “civilized” societies — the pale-skinned peoples of northern climes were unjustly viewed as innately inferior just as much as darker-skinned peoples of the tropics were. In fact, the Arabs of the Umayyad era classed the Iranians as racially “red,” lighter-skinned and lighter-haired people than the Arabs, and subjected the converts to Islam among such people (called “mawali” or clients) to institutional discrimination on a racial basis (despite the shared religious affiliation with the conqueror). The classification “People of Color” is a Western “post-modernist” construct, designed to create solidarity amongst dissimilar groups in Western nations, requiring a shared foe (“white people,” a term referring ostensibly to a “system of unparalleled brutal oppression” but to most people referring merely to people of native European descent). Without that shared foe, the artificial coalition of disparate peoples would collapse. If Iranian-Americans wish to identify as “People of Color” in order to flee from the negative connotations of “white” as uncultured and oppressive, so be it. If Iranian-Americans wish to view themselves as natural allies of their historical Arab and Turkic oppressors against all fair-skinned peoples of native European descent, let it be so. Do not expect me to view it as anything other than a ploy to escape association with the “devil in human form.”

Iranians are Iranians. When they have a section for that I check it. I am not middle eastern (middle with respect to what??) I am not a color (white, brown, yellow people of color etc.) Iranians are a mixture of natives of Iranian plateau such as people of Elam and Aryan, Semites and other groups of people. We are heir to the first civilizations of mankind and deserve respect for our contributions to humanity which has been constant. We do not need simple categorizations.

Some day, we humans will learn to redesign bio-information forms to ask of a person’s heritage rather than use an artificial notation of “Race” which is a man-made construct based on a notion of “My race is superior to other races”.

Race has no definition or existence from a scientific stand-point—there is no such thing as a “Race Gene” or a racial genetic marker.

If we want to talk “Race”, the more accurate an transcending descriptor is “The Human Race”.

The Writings of the Religions refer to people by their color sometimes—but that is so as to parallel how the people of the time of Revelation think of themselves and “others”.

Modern humans migrated from Africa about 50,000 years ago, according to population genetics.

All peoples of the world(e.g., Ancient Iranians, Chinese, Native Americans) are descendants of this wave of humans who made a journey out of Africa to all corners of the planet.

The diversity of skin hues, facial features, hair type, and other phenotypical features are the result of necessary changes required in response to the environment as we moved to different latitudes and biomes.

Its wonderful to be proud of one’s heritage; and Iranians, Greeks, Ethiopians, etc. should be proud of their contributions to world civilizations. But to let that pride develop into myth-making whose purpose is to exalt one’s group over others is where we step into a realm of error and group/racial egotism. This sort of thinking is dangerous for humanity.

As Baha’ullah states—“The earth is but one country and mankind its citizens”(19th Century)

Just my thoughts as a Baha’i. I have since developed a pride in humanity that goes far beyond my African-American heritage. Does this not seem to be the appropriate mind-set for this Day and Age?? A mind-set informed by Religion and Science.

Well said! I am also a Baha’i and half American and half Iranian, married to an African American. My children from two different marriages are Polynesian, and my other child is half African American and 1/4 Iranian and 1/4 American- European descent. We consider ourselves “human”… a true global household.

Just a thought—Isn’t it a bit odd and totally unscientific that the various groups of people according to their heritage, color, race tag, assume that they just popped up out from the soil, so to speak, ready-made to look as they currently do?

I may be wrong, but I don’t believe the Creator had a cookbook, wore an apron, and in the “earthly kitchen” made up a batch of Iranians, Mesopotamians, Somalis, Chinese, Inuits, etc. put them in an oven at different temperatures, and dispersed the outcomes with the “Divine Spatula”

at different spots on the earth.

Just a crazy thought of mine.

As a possessor of “white privilege” I accept that there are advantages to looking like the (barely) majority population. But i believe that significant discrimination in the U.S is almost entirely directed at Afro-Americans and Latinos. Iranian, Indo And Chinese Americans score average or above on all economic indices. I think the issue for Iranians is an internal one -“Am I white?” and that internal dialogue is pointless and destructive.

Very interesting article. my experience was that , during my childhood I was discriminated against, verbally abused in school for my Iranian ethnicity. Not being considered “a person of color”, I didn’t enjoy the protections that were in place for people of color, because of past abuses against them. I’m half German descent and half Iranian. We lived with my mother and lived among the poor. i didn’t have the protection from discrimination that perhaps wealthier children had attending private schools. The way I see it, not being considered “people of color” is an extreme disadvatage to ethnic Iranians. We have the discrimination that people of color have, perhaps even have it worse, but don’t benefit from the protections of belonging to a recognised oppressed group. For example, affirmative action in obtaaining entrance to particular schools or gaiig employment where a certain percentage of minorities is required.

I think Iranians should classify themselves as other. As far as my experience goes, white usually refers to people with Nordic features, at least in America. I’ve actually heard people asking what race non Nordic looking Italians, Spaniards, and other southern Europeans with dark features were. Its a fact that white most certainly is associated with Nordic features whether you’re French or Iranian or Pakistani, if you have blue/ green eyes with brown/ blonde-yellowish hair and are Caucasian you are deemed white here. Some South Asians (some Iranians, some afghans, few people from the Indian subcontinent) can pass for white but they’ll usually have northern europid features. Honestly I’ve never been called white or even classified myself as such and I’m positive others don’t see me as white. I do have light skin with dark features but like I mentioned before. White appears to refer to northern Europeans with Nordic features and not people with darker features. Besides white is not a race but merely an inappropriate term used to refer to groups of people who colonized much of the world or belong to the Germanic ethnic groups. That term was given to them to express a sense of superiority towards all other ethic groups but it never defined race and still to this day does not. Iranians are Caucasian but given the qualifications that are needed to be considered/ viewed as white, most Iranians can not be white. Armenians and Azeris are a different story as some do have direct European dna as the Europeans did descend from around that region so they’ll usually look middle eastern, Slavic-middle eastern, or just plain Slavic. Whether you’re arab or Iranian or indian. In America you’ll almost never be considered white and you’re status as Caucasian is even debated to a variable degree. Fantastic Article!

I’ve seen this piece being shared on the Ajam page recently and it’d be fantastic to see the author update this piece as it’s been two years. What are some of your thoughts about the reactions to it? Has the issue of class and different diasporic experiences been brought up in conversation?

The experience of Iranians living in LA is extremely different than Iranians living elsewhere re: class and reasons for migration. Many Iranians living in LA who are part of the elite upper class may have more of a desire to be, and have an affinity to whiteness. This is also linked to how many of these Iranians migrated to LA as Shah supporters. Reading your section on race formation under Pahlavi was very interesting to read.

From my personal experience growing up in a working-class Iranian community in Canada, none of us have ever been identified as white or identify as white, and many of us do identify as People of Colour. Many of our families were working class in Iran and continue to be in Canada. Many of our families came here as political refugees and were not Shah supporters.

While there are many Iranians living in Canada who have the desire for ethnic validation by the state, we also have in Canada a three-decade long history of Iranian diasporic and transnational activism. There is also a history of political involvement by Iranian Canadians in anti-racism, feminist, and labour movements in Canada; granted this is not the majority of Iranians living in Canada but this history of social movement building is often not recognized or rather, is not known by many. I use these examples to think about how perhaps the differences in diasporic formation and class backgrounds impacts the ways our bodies are read in these different countries and the ways we self-identify.

We can also look at Halleh Ghorashi’s piece “Giving Silence a Chance: The Importance of Life Stories for Research on Refugees” where she interviews Iranian women who were involved with leftist organizing during the 1979 revolution. In her research, Ghorashi interviews women living in the Netherlands and in LA What she discovers is that the women in the Netherlands have never felt welcome and face societal and systemic racial discrimination whereas the women she interviewed in LA claim to not feel as discriminated against and when they do, they brush it off (very similar to what you wrote above in your article re: blaming it on American ignorance).

My examples above are not meant to disregard the critically important points you raise–especially on issues of how many of us do experience light-skinned privilege.

Your piece raises so many issues many of us who are dedicated to anti-racism, decoloniality, anti-imperialism, and anti-capitalism are thinking about and reflecting on in regards to not only our own positioniality but also the communities we are in.

I’ve been wanting to figure out a way to respond to this piece since reading it and I haven’t seen many non-American Iranians in the comments, so I just wanted to pipe in with my own reflections.

Some highly dubious assertions are made by this commentator:

Re: “Many Iranians living in LA who are part of the elite upper class may have more of a desire to be, and have an affinity to whiteness. This is also linked to how many of these Iranians migrated to LA as Shah supporters.”

I’m not sure if the writer is contending that the Pahlavis enjoyed the support only among “the elite upper class”. Surely, they remained in power from 1921-1979 more than just with the support of “the elite upper class”?

Re: “Many of our families came here as political refugees and were not Shah supporters.”

As if the two categories are mutually exclusive?!? In fact, supporters of the Shah were one major group of refugees from the Mollah Regime. And it’s interesting that the writer mentions political refugees without stating whom they were fleeing from? Could it perhaps be that they were fleeing to the “Satanic”, evil, “imperialist” West from the same Mollah Regime that the Islamist-Leftist alliance brought to power in 1979?

I can really relate to the segment about claiming to be Italian even though I am Iraqi and not Iranian. My two brothers always pretended to be Italians as teenagers especially when wanted to date white girls. One of my brothers even changed his name to “Tony”. Me on the other hand, never claimed to be anything other than Iraqi

Was reading about the casting of DiCaprio as Rumi and then did some more and more research into identity politics and race in Iranian American/Canadian communities and came across this thought provoking article. I thought I was well done and with a critical assessment but also a personal view of figuring out where a person of Iranian descent fits in this very black and white paradigm of race in the US and the imaginary color line all POCs seem to put ourselves on. Our current artifical notion of race is no longer meeting the needs of vastly expanding definition of such and out multi ethnic societies. We need to update or vocabulary and re define how we talk about shared experiences that allow all things like ethnicity/class/religion to intersect. Or we’ll for ever be in these boxes that no longer encompass the totality of our experiences and thus make it harder for us to change them.

I would love to see this article updated with how differences in class/religion impact experience and if that changes how a person in the Iranian diaspora would self identify.

I reposted it on my Twitter Line !

Thank you!

I realize this comment is coming in a little late but this article was so moving to me personally that I had to post it anyway.

I am an Iranian American born in America. My mother was born in Iran but moved to the States at a very young age and my father was born here but both of his parents were Iranian. While I have always considered myself Iranian American, I haven’t always felt very connected to my culture. I pass as white (and therefore benefit from white privilege) and I don’t speak Farsi. I’ve never been to Iran and since my grandfather on my dad’s side was involved with the Shah I’ve always been told it’s a very bad idea to go because of the connection. Since neither of my parents were raised in Iran I didn’t have the typical childhood of a first generation Iranian American. I grew up with no Iranian friends, and while we did still spend time with Persian relatives and eat Persian food, I’ve never felt as connected to my culture as I feel like I should. I also never saw reflections of my identity in pop culture, and if I did it was centered around Arab culture. Recently I have had a lot of trouble identifying my race. I don’t feel like the average white person since I grew up getting picked on for my ethnicity by kids in school and I don’t look exactly like all my white friends, but I feel like calling myself a person of color is almost cheating because I do pass as white to anyone who doesn’t know where I’m from. This is the first article where I’ve seen any sort of discussion on this topic and it’s made me feel a lot less alone, which I’m really thankful for.

I know what you mean, I was born in Iran and for all of my elementary years have lived there. Even though my features always passed as white and blended in easily, I tended to not talk about where I was from and about my culture. I always avoided it in middle school and up until my junior year of high school. All because of many occurrences in sixth grade, where my classmates would call the food that I ate or my first and last name as ” weird”. I even went through a time in middle school where I insisted on people calling me Nelly and not Nahal.

I so appreciate this article. I am white passing (ish, until you learn my name, or peer at me a bit) – a fact only exacerbated by the nose job I desperately hunted down in my teens (my heart breaks for this now, but what did I know? All I knew was what I’d been told about ‘fixing’ my nose.) – with a white father, but very deeply tied to my Persian heritage. I have found my own relationship with race + the term POC to be interesting, to say the least. I appreciate someone diving into it in a way that was thought provoking. I’d love to hear more about this! 🙂

I love all the half Iranians using the word white passing or trying to connect with the POC. This is just a way to be a part of the victim culture. The poor second generation that have been thrown into this cruel world by their parents without any safety nets. My kids are half Iranian and my husband is the person described in this post as the awful immigrant who did not pave the way. Unfortunately the idea that he lowered his head in denial of discrimination is BS. He has never lowered his head. He is a proud person who doesn’t see himself as a victim unlike so many of the people posting above me. The term “passing” for white was used to refer to black people who used their light skin color to their advantage. If people knew they had one drop of “black blood” they would be discriminated against. Today the need to pass for white has no benefit. Look at all the people trying to pass for a person of color. My husband is darker than all you half Iranians. He has an accent and his English is not as good as half Iranians. He came to this country alone as a teenager. It was not his job to make it easier for you to be victims. His parents did not send him here to be a victim, but to be a successful person and he succeeded. Our kids have had an easier life than even I did with all my “white privilege”. I had to work and pay my own way through college (first to go to college in my family). I wasn’t in a sorority. I didn’t have a newer model car. Our half Iranian kids had many perks I only dreamed about. The parent paid education, frat/sorority membership, a newer car to drive, plus so many other things. If they ever were to play the victim card I’m not sure who would laugh louder my husband or me. Please work on being a success and allow the real victims of the world to receive compassion.

I’m an Iranian by both sides of my family.

I don’t support defining people by the color of their skin however I need to say that if there was a form like that I’d just say white because iranians (despite being from different regions, races, backgrounds, … ) ARE mostly white. Iranians are Aryans and Aryans are white even if their skin tone tends to be a bit more bronze compared to a pale-skinned person. (I did pick white for my application form for some college before even though I found that racial question really strange)

And like I said we do have a lot of people from different races so in south of the coutry you may find black-skinned individuals of Semitic origins who come from the ‘deeper’ middleeast but are still Iranians.

As for myself for example, I’m pale-skinned with green eyes and light brown hair color, many of my friends are also very light-skinned with light-brown, blue, grey, and green eyes. Their hair colors also range from dark brown to actually naturally blonde (and by title only, I’m a muslim). So someone saying Iranians are not white and are people of color or “middleeastern” just proves to me that they’re not knowledgable at all and are proud enough of their ignorance to announce it like that to everyone. What is the “middleeastern” race supposed to be anyway? Maybe they mean the Semitic race which can be found in most Arab and Jewish countries/regions?

I just wish people would refrain from judging when they don’t know anything about a certain subject, like Iranian people who are constantly being called Arabs, ISIS or terrorists or ‘muslims’ by what seems to be the majority of people in other countries … .

This is fascinating. What a great article, and spring board to interesting perspectives. I was born in Iran, left with my family at the age of 7 with my dad’s job to Australia and the only ethnic discrimination I received is when I first came to the US and my Aussie passport says, born in Tehran in 2002, the aftermath of 9/11. Unless people know my full name, people think I’m one of the following; British, French, Spanish, Australian, Italian, Greek, Thai, Malay, Iranian, Iraqi, Indian, Pakistani or Turkish. I never get told I look Arabic, Jewish, other European or African. I have always wondered what white means since it’s a nebulous term and includes people generally more tanned than me like sicilians and includes other caucasians (Iranians are literally Caucasian not Semitic) like Georgians, Armenians, so on. I’ve met a Greek lady in the US who called herself a POC. I hate both these terms of white and POC, because they actually do nothing helpful in learning about someone. Knowing your heritage and upbringing, gives me far more of an insight into your life than those labels. I’m also not Muslim (not really religious) and culturally am an Aussie so I am seen more like an Aussie in the US and don’t like hyphenating myself because I am just as much an Aussie as anyone else. Though I do wonder what it would be like to change my name so I completely fit in, my last name is unique, Iranian but also has an international sound to it, and I feel I somehow owe it to the family line to keep it. I wonder if I have ever been excluded from any groups due to my heritage but I know I sadly fit in with people I rather not when some people talk about their prejudiced or simplified views on the Middle East with me very openly and without fear. I certainly haven’t been excluded from any institutions to my knowledge but then again people would be polite about it, wouldn’t they?

Iranians come in a range of looks. Some are totally white-passing, even if they don’t have a white American parent(?), like the blogger. Many others look identifiably and stereotypically Middle Eastern. You’re going to live a slightly different life depending on how “white” you look. That’s the same with all races – black biracial types are going to be treated and seen differently (and better) than blacks with less white in them.

However, if you live in a liberal area, as most Iranians do, I assume (LA, NYC, Bay Area, college towns) – you’ll be seen and treated well and embraced no matter what you look like – whether you’re white-passing or look downright Middle Eastern. In liberal areas, people love their Persians – the guys and girls are popularly known to be “hot” and desirable. If the half-black/half-Persian comedian Tehran is to be believed, it’s a great time to be Persian – they’re famous and beloved.

I see the way Iranians are seen and treated – pretty much like white Americans. Honorary white people. In fact, it can be argued that Iranians ARE white – they are according to the census, and aren’t they Caucasian, pretty much, Indo-Europeans, with a Caucasian-enough look?

I’m not sure if Iranians should be lumped into POC. That would undermine the real struggles, pain, and discrimination other POCs suffer from. Iranians look like some type of white, if not necessarily straight-on white American. Therefore, they’re seen and treated as white-enough, treated kindly, hired, promoted, seen as great romantic prospects, easily befriended, embraced, and beloved.

One half Western European/half Iranian woman wrote that she had her father’s Middle Eastern looks, and she was stopped at the airport twice. However, she also wrote that in her whole life, “I’ve been treated nothing but kindly.” Contrast that to the experience of Asian Americans, who often suffer from rude, hateful, condescending, bullying, and exclusionary treatment – at school, in the workplace, stores, hospitals, and everywhere else. The all-out discrimination and poor treatment of Asian Americans causes them to have some of the highest rates of depression, anxiety, panic attacks, and suicide in America.

I’m saddened to always see that other “POC”, like Iranians supposedly, really look down on Asians, stereotype, exclude, have an automatic megative reaction, and fail to want to get to know. The false and hurtful stereotypes of Asians lives on because all other races do not want to even think of Asians, much less get to know them.

I’m seeing that Iranians are like other races or ethnicities – or maybe even more exclusionary and looking-down towards Asians. I’m here to say that all your stereotypes and beliefs about Asians are wrong. We are NOT all disgusting, low-life, dog-eating, backwards, fresh-off-the-boat, ugly foreigners who can’t speak English. We are NOT all wilting-lily, nerds, accountants, logical, scared, passive, uncreative, incapable of being leaders. We’re mostly the complete opposite of those stereotypes. More than other races, Asians are radiant, creative, open-minded, outgoing, on-trend, inclusive liberal, progressive, forward-thinking, stylish, and cool.

Please Iranians – next time you see an Asian, don’t just turn your nose up in disgust, avoid, fail to hire, fail to give a chance, fail to get to know. Maybe that Asian will bust your stereotypes about them, and you’ll see that they’re wonderful, amazing creatures who are horrifically underappreciated and devalued. Do your part to stop the anti-Asian stigma!

There’s a difference between nationality, ethnicity, and race. Take away the political ramifications of all of those classifications, you can be rational and trace the migration and history of any culture (including language). We are all homo sapiens and bleed the same color but its more ignorant to fall into the traps of warring ideologies.

To preface, I am an Iranian-American, born from two incredibly resilient working-class Iranian refugees. I am white in appearance and even Iranians have addressed me as “safeed-poost”. Despite it being a different form, this does not mean I haven’t faced prejudice and discrimination as a result of not being in the dominant race in America. In my perspective, that means I have “skin in the game”, regardless of what color that skin is. I also recognize that my confrontations with power disparity are drastically different from, say, a Latino living in America, and that I am very privileged by my light skin as well as the resources I have available to me.

That being said, here are my thoughts. There is a dialectic to be considered of equally important and, sometimes opposing, truths. The Iranian-American experience is not the same as the white experience, this is simply without question. Many of the young first gens reading this probably remember the weeks and months following 9/11 and how our race became readily apparent. However, Iranian-Americans are not in the epicenter of racial oppression in America, and much like Susan Silk’s “ring theory”, we should recognize that those in the innermost center ring of trauma/oppression should be given the most support from the outer rings. We, as Iranian-Americans, should know the boundaries of our space and that it overlaps only in some ways with the space held by racial groups who have experienced extreme violence and systemic oppression, such as Black Americans, Latino Americans, or Chinese Americans, just to name a few.

All this being said, I found the author’s article to be hugely inspiring and on point. I loved it. It has brought me to the conclusion that sums up everything that I said as well as my personal feelings from reading the piece—- It is valuable for Iranian-Americans to be proud of our accomplishments, proud of our resiliency despite periods of real oppression (such as during the hostage crisis), proud of the sacrifices made by those before our generation for us to be able to pontificate on these matters in the first place. It is also valuable for Iranian-Americans to be allies for those under the boot of white oppression in this country. Given our experiences, we can at least better approximate the experience of those most affected. Therefore, it is important we stand as allies. I believe THIS is the reason that this author was contemplating if we are POC. Not a superficial ploy to play victim, but rather an opportunity to be part of this greater conversation about equity, because we do have something to contribute from our own experiences, and our voices count.

Let’s just clarify that by “white people” we all know the term is referring to Anglos. It sure as hell wasn’t Russia or Greece that colonized Africa and is bombing the Middle East. Love how people act like they can’t tell the difference.

A white immigrant from the Soviet Union probably has more in common with an Iranian immigrant than he does with a white American. We need to focus on nationality, not skin color.