Queering Iranian Cinema

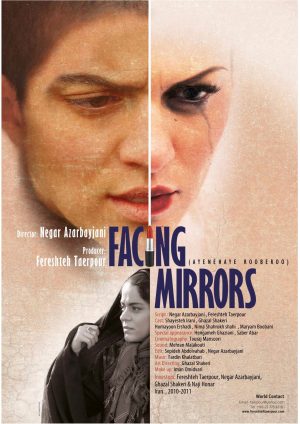

The concept of a queer Iranian cinema may sound contradictory or impossible, but that is exactly how one would describe Facing Mirrors (2011), the first movie to feature a female-to-male transgender main character that has been written, produced, and screened in Iran. Directed by Negar Azarbayjani and produced by Fereshteh Taerpour (two cisgender female filmmakers), Facing Mirrors features the story of the unlikely friendship between the upper-class Adineh (“Eddy”), a pre-op transman in Tehran struggling to escape from the grips of his transphobic father, and Rana, a modest, devout, working class woman who ferries passengers in order to pay her imprisoned husband’s debts and secure his release.

This film has won numerous awards and nominations in over 64 different LGBTQ and international film festivals around the world – most notably the Special Jury’s Crystal Simorgh Award at Iran’s 29th Fajr International Film Festival and the Outstanding First Feature Award at San Francisco’s 36th Frameline Film Festival. It has also received rave reviews from Iranian film critics and audiences around the country.

Although transpeople seeking transition are legally accepted in Iran, they are not often visible in popular culture. The legal acceptance began with a fatwa issued by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1978, which laid the groundwork for the current legal regime dealing with trans issues. Today, not only does the government recognize transpeople, but it also financially supports those who cannot fully afford hormones and sex reassignment surgeries through charity grants, and more recently, by mandating that insurance companies cover the full cost of the operation.

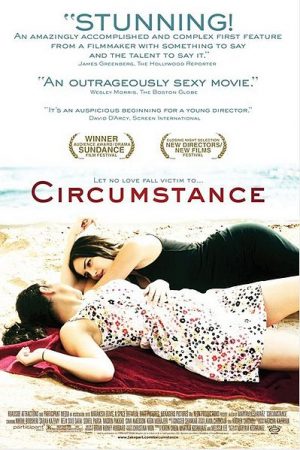

The surprising aspect of this story, therefore, is not the positive response from both critics and ordinary moviegoers in Iran, but rather a lack of coverage by mainstream Western press of such an internationally successful movie. It would seem that a movie about transpeople in Iran would be an instant headline-grabber, especially when one considers the plethora of news reports, op-eds, and airtime devoted to criticizing the Islamic Republic of Iran’s horrid record of human rights violations, particularly when it comes to the rights of women, minorities, and lgbtq folks. Indeed, another recent movie, Circumstance (2011), written and directed by Iranian-American female filmmaker, Maryam Keshvarz, which chronicles the love story of two female Iranian teenagers – Atefeh and Shireen – trapped between a repressive government and an unaccepting society, was immediately picked up by mainstream media. It generated multiple articles, reviews, and critiques, including an interview on AfterEllen.com, a popular US-based lesbian pop culture website.

The lack of mainstream coverage of Facing Mirrors in the US stands in stark contrast to the widespread media attention given to Circumstance, which is a direct result of the Orientalizing effect of the Western gaze on Middle Eastern subjects. Historically, some European men who came into contact with the Middle East both fantasized about and denounced the closed-door sexual lives of Middle Eastern men and women, especially homosocial spaces and same-sex relations. European women, on the other hand, sought to save their Oriental “sisters” whom they viewed as oppressed by their religion and Oriental men, as elucidated by Harvard Professor Leila Ahmed in her book, Women and Gender in Islam. These attitudes toward Middle Easterners continue to this day, an example of which can be found in the movie Circumstance whose relatively positive public reception in the West arises from this conformity to Western Orientalist imaginaries, whereas the movie Facing Mirrors disrupts and challenges the hegemonic and Orientalizing narrative of Iran’s sexual and gender minorities, and is thus ignored and excluded from the cultural and artistic public domain.

Oriental Objects of Circumstance

According to the Iranian-born US-raised first-time director of Circumstance, Keshavarz, the inspiration for making the film was a lack of movies in Iran “or the Muslim world” that dealt with the issue of women’s sexuality. This claim could not be farther from the truth, as there are a plethora of movies in the Middle East and North Africa, let alone South and East Asia that deal specifically with issues concerning women, sexuality, relationships, and domestic problems, such as Caramel (2007), The Girl in the Sneakers (2001), The Circle (2000), The Last Supper (2002) and many more.

Shot in Lebanon, Circumstance often appears inauthentic to an Iranian audience about whom it purports to speak. From the actors’ thick American accents when speaking Persian (for most of them grew up in the suburbs of America) to the natural and urban scenes of Iran to the characters’ costumes and house decorations, there are many instances of disconnect between what the movie portrays and the reality of Iranian life. For example, during a scene when the two girls’ car is stopped by a police search patrol, the girls scream “Comité!” – a term literally meaning “the Committee,” referring to the so-called morality police in the 1980s and early 1990s. However, comités have long ceased to exist and the so-called “morality police” is now referred to as gasht-e ershad or the “Guidance Patrol.”

In addition to the many technical mistakes, the movie has also been criticized by Iranian lesbians and feminists for being extremely shallow and resembling a stereotypical exotic Orientalist fantasy rather than showing the reality of lesbian life in Iran. According to Mahboubeh Abbasgholizadeh, an Iranian feminist activist, the film incurred the wrath of a number of Iranian feminists and lesbians, because it failed to show the realities of marginalized lesbian women in Iran. It is imperative to note that Circumstance was not meant to speak to audiences in Iran, but its main interlocutor was a Western audience in the United States specifically. Indeed, when Abbasgholizadeh claims, “squeezing sex and the government’s suppressive violence and similar subjects is intended to make the film more exciting,” she is touching upon the long history of using Middle Eastern (queer) bodies and sexualities to satisfy Orientalist fantasies of the Euro-American spectator.

Historically, many Europeans who came into contact with the Middle East have often fantasized about the “behind the veil” life in the Oriental “harem,” which has come to symbolize the hidden sexual lives of Middle Eastern women. “In Circumstance, the audience is witness to that very same gaze and objectification of women’s bodies,” writes Leila Mouri, an Iranian women’s rights activist, journalist and Ph.D. Candidate at Columbia University. It is this un-veiling of the hidden lives of queer Middle Eastern women in order to serve men’s pleasures and fantasies that reduces them to mere objects of gaze and consumption for a Euro-American audience.

The greatest weakness of Circumstance is the lack of subjectivity of the two protagonists, Atefeh and Shireen. From the portrayal of a slow-motion erotic belly-dancing scene to the alcohol, drug and sex-filled underground Tehrani parties, Atefeh and Shireen are shown as mere (queer) sexual objects as opposed to subjects of their own destiny. Indeed, the movie’s byline in the official website proudly proclaims in bold letters: “Freedom is a Human Right.” However, in the movie, the Iranian (queer) woman’s struggle for social and political freedom is reduced to drinking, attending parties, playing loud music and cursing the “Mullahs.” Even though this desire for social freedoms is important, its shallow portrayal in the movie simplifies and overshadows the larger social, political, and economic struggles of Iranians, and renders their political agency and complex analyses of their social and political plight invisible. For the Western audience, however, the Orientals never possessed any agency to begin with, and thus, can only exist as mere victims of circumstance.

Reflections in the Mirror

The lack of subjectivity in Circumstance is contrasted by the strong and complex characters of Facing Mirrors. When the protagonist Eddy’s transphobic father discovers his intention to acquire a passport and leave the country, he tries to lock Eddy up; however, Eddy escapes with some money and a backpack on his shoulder, which puts him on the path of meeting Rana. In the movie, instead of being treated to the stereotypical images of the oppressed Oriental woman, one is confronted with scenes of defiance, resolve, compassion, and complexity. For example, when the “Guidance Patrol” stops Eddy and one of his female friends while driving, instead of screaming, Eddy defies the police officer and tries to (unsuccessfully) pass his brother’s driver’s license as his own. This scene offers a glimpse into the complexity that often marks the space for defiance and negotiation between Iranian youth and the state security apparatus. Eddy’s “tough-guy” attitude is, however, tempered by his softness and his pain and loneliness are revealed in a potent scene of crying in the bathroom.

Rana, who is devout and comes from modest means, has her own moments of defiance and struggle. She reveals that, as a young girl, one of her dreams was to learn to drive and be able to stand on her own feet. However, instead of being reduced to a helpless victim when her husband is sent to prison, she defies her overbearing mother-in-law (who doesn’t believe in women driving), and sets out to realize her dream by driving passengers in order to make enough money to care for her son and pay her husband’s debt. Instead of objectifying women and queer bodies to serve Orientalist fantasies, Facing Mirrors shows the resilient and resourceful nature of Iranian women and gender minorities whose struggle for freedom and survival is made possible by exercising their agency. These scenes offer a more complex depiction of what liberation means for the marginalized of society, and it flies in the face of the single narrative of helpless victims trapped under a repressive regime presented by mainstream Western media.

Disrupting Orientalism

The fact that Circumstance has captured the imagination of straight and queer Western mainstream audiences whereas Facing Mirrors has received little media attention in the West reveals volumes about the cultural power of the Orientalist imaginary. Additionally, the lack of mainstream coverage of Facing Mirrors in the United States is juxtaposed with the overabundance of media attention toward the film in Iran where the film has been the subject of debate and appraisal since its release.

Even though Facing Mirrors did not receive its official permit to be screened in Iranian theaters until October 24th, 2012 – almost a year-and-a-half after release in international film festivals – film critics, journalists, bloggers, and state-sponsored news agencies in Iran began commenting and reporting on its laudable success worldwide almost immediately. It has also been the subject of much debate in Iran’s online blogs and news sites where many young Iranians discuss social, cultural and political issues of the day. This film was even screened at Mofid University in Qom, an extremely religious Iranian city known for its seminaries and education of clerics. After a panel discussion with the producers and actors of the film, the Islamic seminary students and professors praised the movie for portraying the realities of transpeople’s lives in Iran. This is a testament to the fact that despite restrictions and problems of censorship in Iran, the public sphere is still open to debate and discussion of a variety of topics, including those pertaining to sex and gender.

The greatest success of the movie, however, is in the fact that it has forever entered Iran’s social, cultural, and political public space where it has inserted a thought-provoking and relatable narrative of queerness in the public imaginary, and addressing a social taboo in consequential ways that Circumstance could never have done. With its humanistic and yet complex storytelling, Facing Mirrors is able to not only touch the hearts of its audience, but it also manages to explore the viewers’ own preconceived notions about transgender people in a manner that is not moralistic or heavy-handed, while truthfully portraying the reality of being trans in the context of Iran’s society and culture. Unlike Circumstance, Facing Mirrors has the power to confront, challenge and continue the process of uprooting prejudice in Iranian culture, and potentially open up the public space for discussing other taboo socio-cultural topics in the future. Facing Mirrors is, in fact, queering the exotic image of the Oriental subject for a Western audience, as it humanizes Iranians and contextualizes their struggles.

Unfortunately, the mainstream Western culture considers such complexity as antithetical to its Orientalist narrative of oppressed Muslim women and queers in need of saving. Therefore, a movie such as Facing Mirrors finds itself as an oddity in the Western cultural and public space where such nuances are rendered invisible or, at best, ignored. Indeed, Facing Mirrors not only sheds light on Iranian social issues, but it also holds up a mirror of reflection that exposes and disrupts Western Orientalist imaginaries, and paves the path for a new and complex understanding of the Middle East.

21 comments

I think your orientalist argument for why Facing Mirrors is receiving less Western media attention than Circumstance is reductionist and ignorant of the complexity of the entertainment and media industries in the US. Facing Mirrors, unlike Circumstance, did not win an award at the Sundance Film Festival, which is a major pipeline for emerging independent film directors to garner mainstream US media exposure and possibly break into the commercial film industry. If Facing Mirrors won a Sundance award, we’d most likely be reading about it in the Huffington Post and elsewhere. Also, I find your use of the Western term “queer” (and its particular history, meanings, and uses in the West) problematic and confusing when trying to discuss “authentic” narratives of Iran’s sexual and gender minorities. The term “queer” is most definitely not used by the religious establishment/government to discuss transsexuals in Iran. Trans identities are often described as a “disease” and sex-change operations as the “cure” in the Iranian public discourse. Finally, your comparison of Circumstance (as bad) and Facing Mirrors (as good) is lopsided since trans and lesbian/gay/bisexual narratives are seen as distinctly different and separate by the religious establishment/government in Iran. Transexuality is legal and homosexuality is not in Iran. Why is that? Probably because the religious establishment/government is of the reductionist opinion that trans people are really heterosexual people born in the wrong body! This opinion is probably offensive to many Iranian trans folks and misrepresents how they perceive and narrate their own gender/sexual identities. We consumers of media/entertainment don’t know what Iranian trans folks actually think and feel about their own identities since there’s so much media noise about orientalism/occidentalism in the West and Middle East drowning their voices out and making it too dangerous for them to speak up.

Thank you for the comment. I am going to address your points one by one.

First on comparing Circumstance and Facing Mirrors as “good” and “bad”, you wrote that my comparison is “lopsided” because these narratives are explained differently by the Iranian government/religious establishment. However, this article isn’t about assigning worth to either movie or either narrative of identity by the Iranian government; it is not about “good” vs. “bad” but rather about exploring the technical and cultural weaknesses of the movie Circumstance and why it is hard for many Iranians to relate to it. This analysis is explained in more detail by Leila Mouri (whom I quote in the article: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/leila-mouri/circumstance-movie_b_1071653.html) and an english translation of another article also talks about the weak points of Circumstance here: http://w–o–r–d–s.tumblr.com/post/35247949616/let-me-hear-you-depoliticize-my-rhyme (And you can find the original Persian available here on Mardomak: http://www.mardomak.net/story/64658). Facing Mirrors has a lot of strengths as a movie and does not have the same weaknesses as Circumstance (which in my mind are important). So I’m not sure what you mean when you say that my comparison of these two movies is “lopsided.” I don’t think I posed the same-sex desires of the two protagonists in Circumstance as an “inauthentic” narrative of Iran’s sexual and gender minorities while FM showed an “authentic” image of these minorities. But rather that the way these desires were filmed and portrayed in Circumstance were both unrealistic and problematic (for all the reasons already listed) while FM showed a much more realistic, complex, and full image of social problems facing gender minorities. Can the upper-class Tehrani protagonist of FM who flees to Germany be representative of ALL transpeople in Iran? Of course not, and I would never suggest that.

You wrote: “Transexuality is legal and homosexuality is not in Iran. Why is that? Probably because the religious establishment/government is of the reductionist opinion that trans people are really heterosexual people born in the wrong body! This opinion is probably offensive to many Iranian trans folks and misrepresents how they perceive and narrate their own gender/sexual identities.” I’m not exactly certain what you mean by these sentences, and even though I have an inkling, I’d rather not assume or put words in your mouth, so I will refrain from addressing this point.

As far as terminology goes, you are right that the word “queer” has a very distinct American history and the Iranian government most certainly doesn’t use this terminology. This word is used differently in different contexts. Some find it extremely liberatory and some find it offensive. However, in academia and activist circles the word “queer” has recently been the preferred word of choice. On the one hand queer is an inclusive umbrella term that inclues LGB and (some) T people (along with a whole host of other identities). On the other hand when academics talk about “queering” something, they are talking about “complicating” the issue and studying something against the mainstream accepted ideas of gender, sexuality, and more recently race, ethnicity, and entrenched systems of power, etc. This is something that in the US was born out of the explosion of Queer Theory in academia (who got their cue from queer activists on the ground and theorized about it), and it is also how I have chosen to use the word in this context. Here is an essay about the use of the word “queer” as a verb: http://www.charlieglickman.com/2012/04/queer-is-a-verb/

And I am very well aware that many transpeople in Iran (or the US) do not identify as queer, especially because of the word’s association with “homosexuality.” Due to restrictions in Iran and the struggles that trans folks face, some transpeople don’t want to be associated with homosexuality. This is why we titled the article “Queer and Trans Subjects in Iranian Cinema.” However, it is also presumptuous of you to assume that the “disease/cure” rhetoric used by *some* government and religious establishment officials is automatically offensive to transpeople. Even though in recent years, in the US, many transpeople have discarded the medical model of transgenderism for the social model, there are also many transpeople both in Iran and the US who do see their trans-ness from a completely medical perspective (i.e. as either a flaw, disease, problem, a biological process that needs to be resolved/ addressed). However, this does not mean that they want to be treated by their families and society as a diseased object. There are many transpeople who, after having gone through hormone therapy and SRS, would not want to even be identified as a “transgender man” or “transgender woman” and want to simply live socially as men or women. In the context of Iran’s bureaucracy, this is a legal and medical path that is provided for those who are seeking transition. I don’t think we can claim that this model is not useful or even not liberatory for some people.

However, it is also true that there are many trans folks who do not want hormone therapy or SRS, and there are also people who don’t identify as completely male or female socially. Considering that Iran’s government along with most other governments out there only legally operates on the gender binary (the two notable exceptions that come to mind right now are Nepal and Pakistan who allow a third gender category), then people who don’t fall into a social M or F category don’t have much of a recourse legally, except to choose one or another. For example, Iran and Islam in general do recognize intersex people; however, legally in Iran, they have to fall under either “male” or “female”. A lot of this has to do with gender-specific legal codes (e.g. inheritance rights, etc), which can be critiqued in its own right.

And finally, I don’t think you can presume that “we consumers of mass media” haven’t done research or activist work, or don’t know anything about what transpeople in Iran want. I agree that there is a lot of media noise out there, but it is certainly not critiquing orientalism in art and culture that is drowning out the voices of the oppressed.

I agree with your article in so far as its criticism of the movie Circumstance goes and while I have not been able to watch Facing Mirrors yet, I have read and heard about it enough to agree that its narrative is definitely a lot more nuanced and thought provoking than that seen in the Circumstance.

But I have serious problems with your celebratory tone on recognition of transsexuality and permissibility of sex change operations in the Islamic Republic. I am afraid that you are being totally oblivious to the homophobic context within which Iran’s official discourse on transsexuality is taking shape. Unfortunately, you do not seem to realize the whole complex of psycho-medical, legal and social forces that are at work to compel individuals who express same-sex desire and non-conforming gender behaviors to ‘trans’ themselves and undergo aversion therapy, hormone therapy, and other medical operations.

You speak in a congratulatory manner of the government financially supporting those who cannot fully afford hormones and sex reassignment surgeries through charity grants. This is while Iran is failing to ensure that sex reassignment surgeons and other health care professionals dealing with the community meet even the minimum standards of education, skill and ethical codes of conduct. Do you know that there are a staggering number of people who suffer from serious infections and permanent and irreparable physical damage (e.g., recto-vaginal or urethral fistula, vaginal or urethral stricture partial, complete flap necrosis, paralysis, chronic chest pain, severe back pain, etc.) as a result of substandard sex reassignment surgeries? Do you know of the community’s painful stories of abuse and harassment at the hands of health care professionals? Do you know that the overwhelming majority of transgenders in Iran self- administer hormones in a rushed manner and without a proper understanding of all the negative effects that hormone therapy can have upon their bodies? (They do so in part to be able to appear in public without attracting harassment and abuse). Have you had any interaction with the many individuals who regret the medical/surgical choices that they were led to make and suffer now from serious depression and suicidal thoughts?

You claim that there exists a public space in Iran where issues relating to (trans)sexuality and gender can be openly debated (your Qom example particularly strikes me!) This is while homosexuality is criminalized by the death penalty and any positive mention of it can attract criminal consequences. At the same time, transsexuality is framed as a disease in need of cure and surgery.

Based on your response to the comment posted below your article, I can say you do not simply realize that what is being defined as transsexuality in Iran’s legal/medical discourse is very different from what transsexuality is understood to be in the West. I have come upon over a hundred accounts from applicants who have appeared before the Legal Medicine Organization of Iran (LMOI), which confirm that the psychologists in charge of granting sex change requests in Iran are deeply homophobic and sexist and often link any expression of same-sex desire or gender non-conformity to transsexuality! (You may think I am exaggerating but we have been told in so many interviews that they ask applicants about how they brush their teeth to find their gender inclinations!!!! There is no shortage of such ludicrous questions marked by deep-seated homophobia and prejudiced obsession with female-male binaries.)

By Criminalizing homosexuality, imposing compulsory veiling, punishing cross- dressing, and making gender recognition dependent upon hormone treatment, sterilization and sex reassignment surgery, the Islamic Republic is effectively leaving individuals who transgress gender/sexual boundaries with two mutually exclusive options, both of which pose an equal risk to their health and safety: to seek risky, costly and invasive medical operations or to live a life unremittingly overshadowed by harassment, discrimination in access to employment and education, arbitrary arrest and detention and threat of torture and other ill-treatment. You cannot compare this situation to that in European and North American countries that protect individuals from discrimination on the ground of sexual orientation and gender identity but still make surgery a prerequisite for legal sex change. May I also note that a lot of European countries have within the recent struck down the requirement of surgery for the legal recognition of the gender identity of transsexual people as unconstitutional on the ground that it “constitutes a massive impairment of physical integrity”.

Iran reportedly carriers out more sex change operations than any other country in the world except for Thailand. This must be a cause for concern, Individuals as young as 20 are being, directly and indirectly, pushed to make irreversible and potentially harmful decisions about their bodies without having access to accurate information about issues relating to gender and sexual orientation and without having the opportunity to have a safe real-life experience in their desired gender. Many of these individuals might not be as inclined to identify as members of the other sex and opt for sex change operations if there was less legal and societal condemnation of homosexuality and more leeway in traditional masculine and feminine role behavior. Many of the ‘butch’ lesbian and transgender persons I have interviewed indicate that their experiences of stigma, rejection and violence played a determinative role in their motivation for sex reassignment surgery.

In conclusion I recommend that you watch this video clip of Larijani , the Head of Iran’s Human Rights Council in the Judiciary. In this interview with the State television, he says: “Homosexuality is an illness, a very bad illness. Therefore, forming assemblies and associations to promote homosexuality is an offence for which there are harsh penalties under our law and we will enforce these rigorously. But for isolated individuals, we are not in favour of beating and bullying. These are patients who must be cured. They must be placed under special psychological treatments and at times even physical and biological ones and we must have a clinical approach toward these people”: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m3N4gRd2gAA

Thank you for the comment.

I don’t think you can assume what I am or am not aware of, just based on what I have written in this article and my response to the comment above.

The paragraph in the article that you mention was put there to give readers some context about the permissibility of sex reassignment surgeries under law in Iran, since we thought that some readers may not be aware of this fact. Addressing all the medical, social, and legal obstacles that Iran’s sexual and gender minorities face in a 2,000 word article that was about the problem of representation in the US would have been impossible, and would have detracted from the main argument of the article.

Unfortunately, unless you dedicate an entire study to this issue, it would be very difficult not to leave some points out or to cover the issue extensively. Even you generalize about the situation of transpeople in the US in your comment when you say that transpeople are protected from discrimination in the US. I can tell you as a fact that that is not the case since the treatment of the issue varies from state to state. Many transpeople in the US are harassed (no less by medical and psychological doctors), discriminated against in job and house applications, bullied, imprisoned, raped, and etc, similar to what many transpeople face in Iran, and a lot of other countries in the world.

But I am not going to dispute some of your other points about what transpeople face in Iran both at the hands of society and at the hands of the government. And I am glad that this issue is getting exposure and generating debate.

“Unfortunately, the mainstream Western culture considers such complexity as antithetical to its Orientalist narrative of oppressed Muslim women and queers in need of saving.” Why did you choose to describe LGBT people as “queers”? I am well aware of the academic practice of using the term “queer” in reference to gender and sexual minorities, although as someone who has had that word used against me as a slur I don’t particularly like it. However, surely the dehumanization inherent to using the word “queers” as a noun is apparent? I am not “a queer” nor is anyone LGBT who choose to describe their sexuality as queer.

Thank you for your comment.

There are two reasons to use the word “queer”: 1) queer is usually used as an umbrella term that includes all gender and sexual minorities, including lgbt people, though there are some transpeople who may not identify as “queer” or they may identify as both queer and trans. 2) queer actually started being used in the US mostly in youth activist circles as a reclaimed word before it became widespread in academia. It is a political term meant to imply a radical, political, and anti-assimilationist understanding of gender and sexuality as opposed to more mainstream gay, lesbian, and bisexual categories that tend to box one’s identity rather than liberate them. Queer has a lot of fluidity and is a source of empowerment for many people who use them. Even in the context of Iran the term دگرباش “degarbash” has been used as the equivalent of “queer” in many circles, though it is not as widespread. I realize that “queer” has had a long history in the US and has been used as a slur against a lot of people, especially older people who do not want to reclaim the word, and that is completely fine in my opinion. However, its use is becoming more and more widespread in the lgbt and wider community.

The reason I use “queer” in this article is because this word has enough flexibility to imply a fluidity of gender and sexuality, especially because many people do not identify as “gay” or “lesbian”, etc but they still have same sex desires or they transgress norms in their gender and sexuality. I am definitely using the word in the empowered and reclaimed sense and it also works as a stand-in for saying “gender and sexual minorities” all the time.

Here are some other resources that you can check out:

http://feministing.com/2010/06/16/whats-the-difference-between-lesbian-and-queer/

http://queersunited.blogspot.com/2008/05/open-forum-queer-liberationist-or-gay.html

http://www.transqueerwellness.org/terms

Hi, I am a big lover of Iranian cinema. FM looks like a good film to watch, I plan to do it. Thank you for your article

Now, my 2 cents

Orientalism is a tool of Western imperialism. Anti-Iranian politics of USA are shown even in propaganda films like C. No wonder they got a big press in the USA.

I am from former USSR so I am very skeptical towards USA “liberation” of peoples in far parts of the world. Usually it is all about the same imperialism and colonialism. And, by the way, there was a great cinema in the USSR, censure and so on notwithstanding. I could tell you that Iranian films often remind me in a good way of old USSR films – they treat life seriously and deep, there is a genuine humanity in them.

I wish Iranians the best and first of all – the freedom from NATO/Zionist threats.

not sure the OP answered your question…

i identify as queer and call myself a queer. i don’t find it dehumanizing unless it’s coming out of the mouth of someone trying to use it as such. i also was lucky to grow up with a relatively low level of verbal harassment so my relationship to the word– both noun or adjective — is likely to differ from yours.

sidebar @shima: not sure if this is a cultural difference or not, but i’m trans and have so far only read trans folks written as two words: “trans people” instead of “transpeople” –to me the latter actually feels a little off, like the word “person” isn’t sufficient for a trans person. again, not sure if its a cultural dif and i haven’t seen it before or what, but i’m curious.

Thanks for the comment. You have a very valid point. I think the convention that I’ve always seen has been “transpeople” and then “trans” as a separate word when writing phrases such as “the trans community” etc.

However, more recently people are writing Trans* with the asterisk marking the diversity of the community and not just transsexuals.

This: http://itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2012/05/what-does-the-asterisk-in-trans-stand-for/

And this: http://youknowyouretrans.tumblr.com/post/3527011536/what-does-the-asterisk-after-the-word-trans-mean

I think the word “transpeople” is more familiar to more mainstream audiences who are not part of the community, which is perhaps why I used it. But your point is definitely well-taken. These terms continue to change and evolve in their usage and meaning and it would be good to keep this in mind for future writing!

You wrote:

“And finally, I don’t think you can presume that “we consumers of mass media” haven’t done research or activist work, or don’t know anything about what transpeople in Iran want.”

I think it is presumptuous of you to think that you “know” what transpeople in Iran want. You can only “know” if you are an Iranian transperson, everything else is a viewpoint or educated guess.

Having worked with North African/Muslim LGBT refugees before, I can tell you that as an activist you can only be an ally and possibly an advocate if that individual trusts you enough to give you permission to do so.

I still find your cherry picking of American queer terminology to critique what you perceive to be an orientalist narrative deeply problemmatic. I understand that “queer” and “queering” is the popular and fashionable term in academic circles when discussing gender and sexuality. However, my graduate studies in anthropology stressed how one must be aware of his/her/their own positionality and employ reflexivity to appropriately situate knowledge about non-Western sexual and gender minority cultures without forcing your own biases and ideology on those cultures (and when talking about them). Just because “queer” is the popularly accepted term in academia does not mean it is the appropriate one to use. By using these terms, you are creating an orientalist narrative in your critique of orientalist fantasy in film.

Thanks for the follow up. I didn’t want to imply that I “know” everything about trans folks in Iran. I guess “know” is a loaded word, since knowledge is inextricably linked to power structures. What I meant to say is that I am not entirely clueless on this issue and I have done a lot of research and activist work over the years. Again this article is addressing orientalist representations in movies, but nowhere in the article do I claim that I speak for all trans people. I think this brings up an interesting point: can those who have a critical perspective on oppressive systems, have a decolonized analysis and speak against oppression even though they themselves haven’t experienced it firsthand? I read an interesting blog post by another graduate student about this, which even though it deals with a different topic, might be worth checking out: http://neocolonialthoughts.wordpress.com/type/aside/

This is where language becomes a limiting factor (as much as it can be enlightening and liberating). If I were writing this article in Persian and my audience were Iranians or Persian-speakers, then I’d be using different words and perhaps framing the issue differently. However, since I am writing this article in English for an English-speaking audience, I am using terms that are familiar to English-speakers (also considering this isn’t an entirely academic journal; we are technically a semi-scholarly website so we have to balance being accessible to non-academic crowds). As far as terminology goes, I did try to use phrases such as “gender and sexual minorities” or “same-sex desires” throughout the article along with the word “queer.” I didn’t use “gay/lesbian” because I think they are more problematic for the purposes of this article and you can’t actually categorize the movie “Circumstance” as a “lesbian” movie (for a lot of different reasons).

I am not sure what you mean by “forcing your own biases and ideology on those cultures.” What sort of cultural ideology do you think I am imposing on Iranian culture? I agree with you regarding being aware of our own positionality vis-a-vis other communities, especially ones that we are not a part of. But here you are making an assumption that I personally am not part of the gender and sexual minority communities in Iran. I do want to acknowledge that the word “queer” could be problematic for different communities and many people do reject the term for different reasons, but I don’t think by using the word “queer” in this article I am creating an “orientalist narrative.”

I don’t see how you can have a “decolonized analysis” of an oppressive system when you are not being clear about your own positionality or employing reflexivity in your article. My point is your article needs more self awareness of how your experiences, identification with particular groups, and current residence in the West color your argument and confuse the purpose of this article.

I still think your orientalist critique about Circumstance is weak and pointless. Like Hamid Dabashi said about Circumstance, “that any attention, cinematic or otherwise, to taboo subjects is both inevitable and ought to be judged on their artistic virtues and achievements rather than their social or political messages” in http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2011/08/27/circumstance-movie-how-lesbians-live-in-iran.html .

If anything, your orientalist critque comes across as a condescending attitude towards American-born Iranians exploring their own complicated relationship to Iran and their sexuality in film. This is why I said your argument in lopsided since you are comparing an Iranian film to an Iranian diasporic (not exile) film.

Worst article ever. As Iranian and LGBT-person, I had never been this insulted and offended by just reading this article!!

Not only this is a major pink wash propaganda article, glorifying the harsh conditions and the lack of rights to sexual minorities! You also are denialist and completely ignorant over the regimes way of persecuting the LGBTs and by its society. Did you know that sometimes homosexual men had been forced into sex-change in order to save their arses from being hanged!!

As I might understand, you are heterosexual and therefore, you don’t speak for me nor for any Iranian sexual minorities, in Iran or elsewhere. You don’t know what it is like to be sexual minority, so how dare you?!??!??

Btw I’m neither a friend of eurocentrism, Hollywood nor orientalism, but this article is bullshit!!!!

Shame on you!!!!

Sincerely Dana

Dear Shima

Thank you for this eloquent and convincing analysis. I have quoted your work in my thesis 🙂

Kimia

Hi Shima,

I do not know whether you will receive this or not, but I am trying my luck. I am interested in watching FM, but I have not been able to find a DVD via Amazon or ebay. I also checked my school library in the US (and worldcat!). Sadly, no success. I found a link online, but it does not have English subtitles. Is there a way I can get access to the movie with English subtitles. I am aware that it has been shown in the US with subtitles, but not sure how to reach the people. If you could offer any help, i would be grateful!