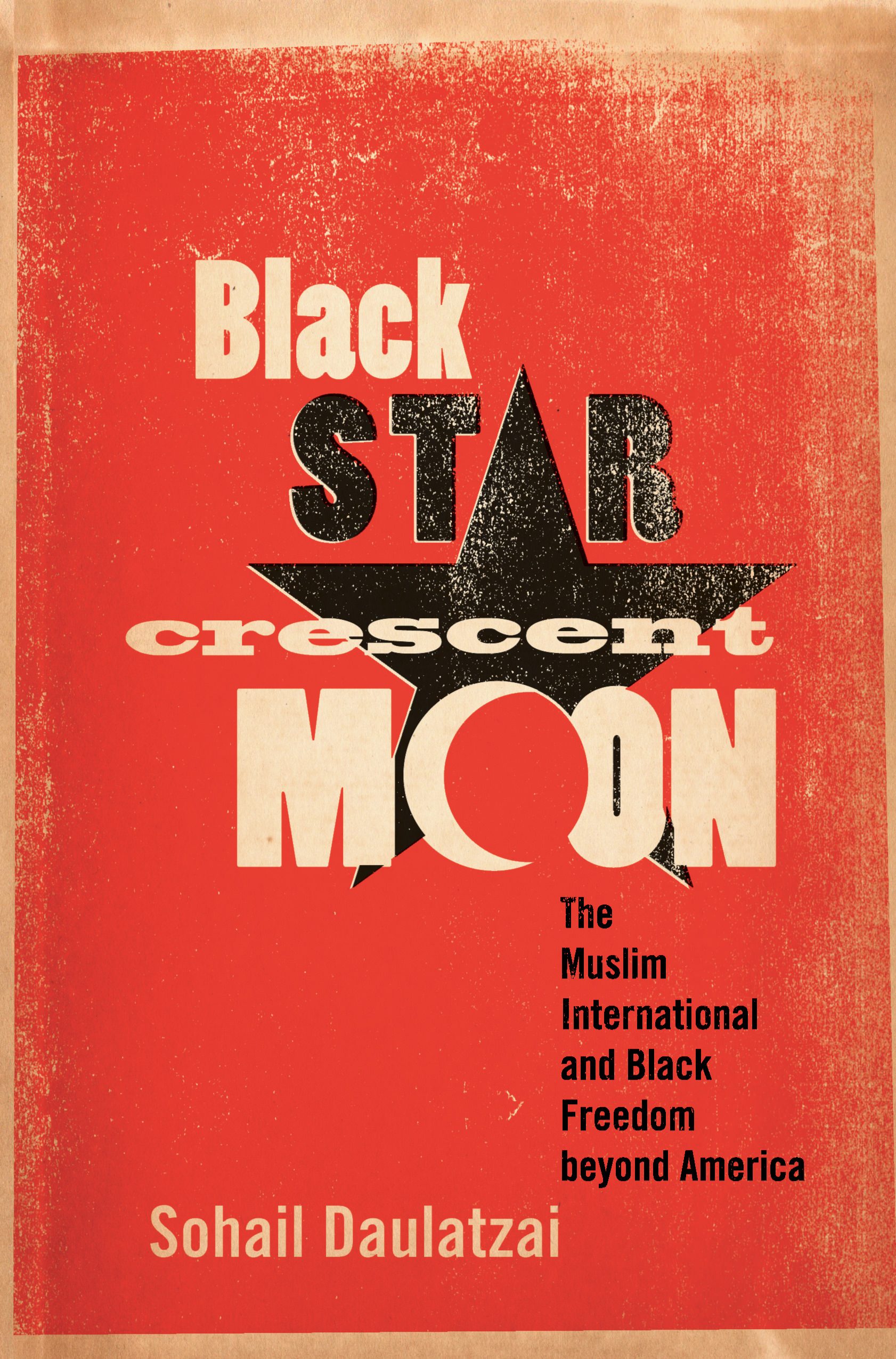

Ajam Media Collective is proud to launch its first ever digital book club, featuring Sohail Daulatzai’s Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Black Freedom Beyond America.

Mark your calendars–we will be hosting live-streamed conversations with the author at these dates:

Sunday, March 8th at 12pm PST: Discussing the Introduction. Chapters 1 and 2

Sunday, March 22nd at 12pm PST: Discussing Chapter 3 and Return of the Mecca

Sunday, April 5th at 12pm PST: Discussing Chapters 4 and 5, Conclusion

Prior to each live-streamed conversation, we’ve invited an outside reader to comment on the chapter readings for that week. This week, Omar Kamran sent us his comments with some questions to get our discussion started.

Omar Kamran currently works as a community organizer in Chicago, Illinois. He is a child of immigrants from South Asia and is a student of sociology, history and Black liberation movements. He left academia in order to build with marginalized communities and be in solidarity with young people on the southwest side of Chicago. Support youth on the southwest side of Chicago by contributing to a campaign to save an after-school program Omar has helped develop over the past 3 years.

***

Sohail Daulatzai’s Black Star Crescent Moon is indeed a timely piece for a generation of Black, Brown and other nonwhite youth to study in order to revisit a period in our collective history where efforts for a unified race conscious struggle in the U.S. and abroad were being forged. This book speaks greatly to the understudied and under-valued moments in history where Blacks in the U.S. internationalized their experiences of oppression and violence in order to connect domestic struggles for freedom to decolonization and independence struggles in the former colonies abroad.

In an era where the Civil Rights ideologies and framework have, for all intents and purposes, dominated national discourse and have effectively rendered Black nationalism as a “failed” and “irrational” framework for equality and justice, this book forces us to revisit this critical period in history to understand that while one man was dreaming of a day when content of character would be more important than color of skin, there were other voices that understood the enemy’s lack of moral consciousness and thus sought to build their beloved community with the darker skinned people of the world instead.

In chapter one, Daulatzai explores the historical, political and economic context of the Cold War and how oppressed Black communities in the U.S. made sense of their oppression in relation to and in conjunction with America’s imperial interests abroad. Daulatzai places a very important and critical spotlight on how white supremacy and imperialism operates and functions when it comes to the rights, needs and well-being of Black people. Much like Mary Dudziak and Derrick Bell, Daulatzai argues that desegregation efforts and passage of Civil Rights legislation by the U.S. was only to save face and protect America’s imperial interests abroad rather than to provide true freedom, justice, and equality to its citizens.

However, Daulatzai provides great detail of how Cold War liberalism impacted the more liberal camps of the Black freedom struggle in the U.S. and how white supremacy effectively severed the ties that were being drawn between anti-colonial struggles abroad and the Black struggle at home. In the height of McCarthyism and the red scare, Black liberals aborted the connection to anti-colonialism and fought exclusively for civil rights and integration at home.

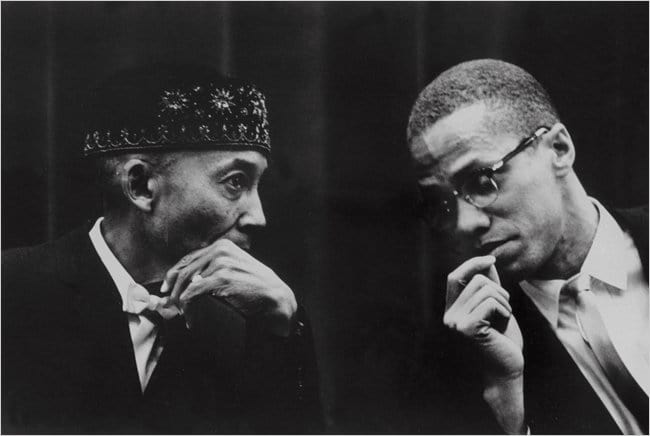

It is at this critical juncture where DuBois’, Robeson’s and later Malcolm X’s internationalism becomes the launching pad for the conversation of the Muslim International. Although the liberal sections of the Black struggle bought into American imperialism in exchange for symbolic gestures of civil rights gains, the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X and other Black radicals had the foresight to strengthen ties and solidarity to the third world. For Malcolm X, anti-colonial struggle and the Black struggle in the U.S. were part and parcel of the same struggle to end global white supremacy.

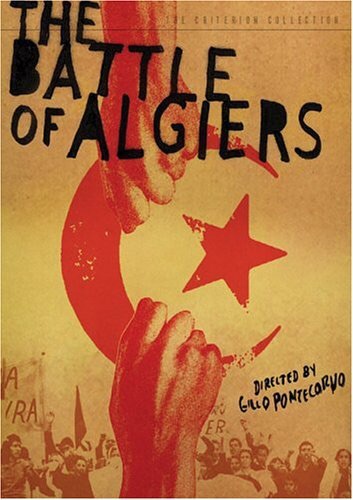

In the second chapter, Daulatzai analyzes the role of Black media in expressing Black Power and the Muslim international. Through literature, film, and music, the growing call for Black Power reached new audiences and created a cultural expression of internationalism between the Black struggle and the third world. The legacy of Malcolm’s critiques of white supremacy and imperialism inspired an entire generation to continue the struggle of internationalizing the struggles of non-white people.

At times, Daulatzai overemphasizes the role and importance of Muslims and the Muslim International in the intellectual imagination of the Black struggle in the U.S. There are points in which Daulatzai attributes the Muslim third world as the overarching influence on Malcolm X’s political thought, suggesting that Malcolm’s politics of freedom are naught if not for the Muslim third world. It is important to state that Fard Muhammad and later Elijah Muhammad taught and practiced Islam that was not an Arabized or South Asian centric understanding of Islam.

The Nation of Islam’s theology served the immediate needs of the Lost Tribe of Shabazz and the founders knew that an indigenous understanding of Islam was the key to Black freedom in the United States. This is why suits and bow-ties, rather than shalwar khamiz and kufis were the cultural expression of righteousness and dignity for members of the Nation of Islam. Moreover, it is important to note that Malcolm used the Bandung Conference in 1954 and the subsequent Non-Aligned Movement that followed as points of reference to show Black people the need to separate from white people and build their own land, not necessarily to repatriate the Muslim third world.

With that being said, there has to be a clearer definition and distinction of what Muslim International is, because at this point, anything having to do with political dissent, anti-imperial tendencies and a Muslim background constitutes the Muslim International. At times, it is difficult to understand where Daulatzai draws distinction between Black internationalism and the Muslim International. Are there any differences for him between the two? Can only Muslims engage and practice in the Muslim International? Is the Muslim International a political ideology, social movement, emotional expression, or cultural identity and does it have temporal limitations?

When John Edward Bruce argues that the darker skinned peoples share a common destiny and that all non-whites should engage in thinking Black, is Bruce engaging in the Muslim International? What does it mean that Fanon hardly ever references or analyzes the role of Islam in The Wretched of the Earth (1961), yet his subject matter is an Algerian Muslim peasant population engaging in anti-colonial struggle? There are some serious analytical and theoretical limitations in understanding the depth and the extent to the Muslim International that must be resolved in order for us to implement and practice Black/Muslim internationalism effectively.

Sohail Daulatzai uses Black Star, Crescent Moon to explore the intellectual and physical connections that militant and radical Blacks in the United States were drawing to anti-colonial struggles for independence in the third world. Understanding the implications of these connections in the past is extremely important, but what is equally important is to explore what these efforts for unity between dark-skinned people mean for us today in a post-civil rights, post-9/11 and for some, a post-racial society. This historical and analytical undertaking indeed becomes relevant when we ask ourselves, what does knowing this history mean for us today?

Surely, there are many parallels between the domestic and foreign policies of the Cold War era and the current ever growing War on Terror. If we truly understand the self-interest of white supremacy and imperialism, we can then find a guiding light in the Black internationalist and Black radical traditions of the past to help us navigate our way through imperialism’s latest efforts to entrench white supremacy on a global scale.

The reality is that the face of Islam and the political landscape of Muslims in the U.S. has changed considerably since the days of Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad. According to a 2007 Pew Report on Muslims, Muslims in the U.S. are mostly middle class and mainstream in their political tendencies. White supremacy has permeated the minds and attitudes of Muslims in America which greatly diminishes the capacity of solidarity building between Black and Muslim communities, let alone the Muslim International.

As a student of Black internationalism in a post-civil rights era, it has been my understanding that people of color must not look to the East and then Blackwards, but rather look B(l)ack in order to move forward as a collective of dark-skinned people. The concept of the Muslim International is needed to help make sense of critical moments in our history; however, many questions need to be answered to strengthen our understanding and engagement in the Muslim International.

JOIN THE CONVERSATION:

What do you think of Chapters 1 and 2? What stood out to you?

Where does Black Internationalism end and Muslim Internationalism begin?

How can we understand Fanon and his relationship with Islam?

How can we make this history relevant for us today? Where do we go from here?

11 comments

If Muslim International is meant to be a catch-all (which I can understand), can we identify what the Muslim International is not? I’m wondering if the phrase smooths out the diversity within the global Muslim community a little bit too much. How can we discuss nuance with this term?

I’m also interested in talking about who found the symbols of the BPP (and others) legible and suitable models for reproduction within the Middle East. The Israeli BPP is an interesting phenomenon–Mizrahi Jews using the symbols of the Black Panthers to call out the Ashkenazi Jews for being racist…Or, another question in a similar vein, how does the Middle East remember Malcolm? This is a region that is not a stranger to anti-Black racism–does that affect readings of Malcolm?

Malcolm’s connection to Asia was an interesting one, and the James Baldwin quote about being the original Viet Cong even more interesting. To what extend do you see war as informing solidarity?

Going off of what Mohammadzadeh posted above, it seems like there’s more going on here than just Muslim Internationalism. Can we make connections with Third Worldism and Tricontinentalism? How does Malcolm’s understanding of race and religion fit into this?

Can we talk a little bit about Malcolm’s autobiography? It seems like the narrative where Malcolm embraces a “color-blind” Islam comes largely from Alex Haley’s account…

I am glad you brought this point up because unfortunately, Alex Haley’s autobiography of Malcolm X is still seen as a valid reference for discussing Malcolm’s politics. If you read The Final Speeches of Malcolm X http://www.amazon.com/February-1965-Speeches-speeches-writings/dp/0873487494

and his writings and speeches post Mecca, Malcolm is very clear that he neither advocates a color-blind or integrationist agenda.

The Muslim International is historically revisionist. While there were earlier attempts at it in the 20th century (al-Afghani) it really didn’t gain wide currency until after the Iranian Revolution in the form of political Islam.

But I’m sympathetic to why Daulatzai has developed this concept. Many if not most American Muslims have a poor understanding of white supremacy and race in the US and our place in it if they understand it at all. The M.I. is a means for Muslims to do just that through the (necessary) lens of Malcolm.