Nearly seventy years after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the remaining Socialist Republics in the Soviet Union declared independence one after another. The technocratic elites of Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Caucasus were no longer subordinate to Moscow and quickly moved to adapt themselves to the new post-Cold War realities. From Berlin to Bishkek, successor governments sought to legitimize their authority by dismantling the highly visible emblems of Soviet power occupying the public sphere. As the monuments of Soviet heroes were pulled from their pedestals, the new regimes turned to figures that were meant to assert national identity—cultivating new interpretations of ethno-genesis through the manipulation of material objects.

In line with his counterparts across the region, president of Uzbekistan Islam Karimov urged the state apparatus to create links between ancient history and current domestic policies. The aim was to ascribe powerful monarchs and literary heroes as the ethnic and linguistic markers of new state-sanctioned nationalism. Statues of Vladimir Lenin and Karl Marx in central squares across the country were replaced with sculptures of the famous 14th century conqueror Amir Timur and the 15th century Turkic court poet Mir ‘Ali-Shir Nava’i— two figures with tenuous historical links to modern conceptions of Uzbek identity and language.

Contemporary scholarship has framed these developments in state ideology and the public sphere as indicators of Uzbekistan’s concerted effort to break from Russian historiography and establish counter-narratives with roots predating both Tsarist imperialism and the Soviet experience. However, if one carefully examines 20th century mechanisms of control in Central Asia, it is clear that Uzbek strategies to resignify historical and literary figures are derived from Soviet historiography and policies of “monumental propaganda.” In other words, although this national project seems on its surface to be rejecting the Soviet version of Uzbek identity, its construction is in fact rooted in the same methodology.

Monuments and Memory: Constructing History Through Statuary

Monumental forms can be traced back to the earliest documented periods of urban society, but they dramatically proliferated with the rise of mass-based politics in 18th century Europe due to their visual directness—their ability to quickly convey political meaning to the public. A monument extends chronologically both into the past and future: it performs a commemorative function, which in turn shapes forthcoming perceptions of an event or public figure.

One cannot divorce the concept of memory (pamyat) from the monument (pamyatnik)—two terms that are etymologically related in the Russian language. As an object engaged in the act of public remembrance, a monument functions as a “site of memory” whereby a social group’s recollection of the past is exteriorized in a physical form.

With the burden of remembrance lifted from the collective, monuments can be utilized by states to create dominant historical narratives geared towards public consumption. As objects imbued with symbolic agency, it is no surprise that certain social groups have a vested interest in destroying them during times of political upheaval.

After the Tsar: Tashkent’s Monuments in Transition

Since the early 1900s, Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, has been a site where monuments and the histories they propagated were often substituted with the changing political climate. Conquered by Tsarist forces under the command of General Cherniaev in 1865, the city became a testing ground for Russian experiments in formal colonial administration, with urban development along Haussmannian lines becoming a major expression of governance. The techniques implemented in France were being implemented soon after in Tashkent, where a colonial European town soon was built alongside (and would later come to overwhelm) the historical Old City.

In 1913, Tsarist forces brought one of the first figurative sculptures to the newly constructed area in Tashkent; a statue of Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufmann, the first Russian Governor-General of Turkestan & the conqueror of Samarqand and Khiva, was placed in the second largest square.

The von Kaufmann statue could be understood as an occupation of public space, supplanting native signs of sovereignty with Russian ones. Once the Communist Party consolidated power in the city in 1917, they renamed the space Revolution Square, tore down the von Kaufmann statue, and in its place raised a large flag of the Soviet Union on the granite pedestal.

The conquering ideology had changed, but as Soviet approaches to urban space in Tashkent would soon show, the approach to claiming space and demonstrating power whose precedent was laid by the colonial authorities was here to stay.

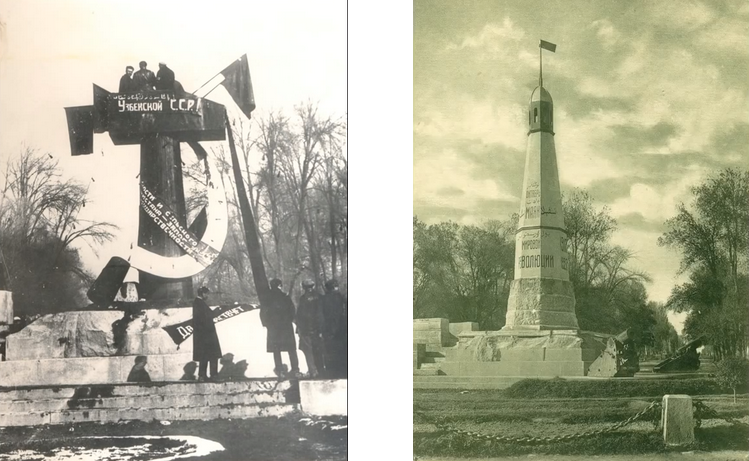

By 1919, the Soviet authorities constructed a large hammer and sickle monument built in the then-popular constructivist style. Tashkent’s hammer and sickle sculpture was a radical break from the standard Tsarist monument; with its geometric lines and experimental form, it looked towards the future as opposed to recording the past. However, due to the regime’s increasing hostility to avant-garde art, the monument was removed in 1926 and exchanged for a hexagonal obelisk commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution.

Revolution Square: Tashkent’s Soviet Heroes

Following the death of Lenin in 1924, the Committee for the Immortalization of Lenin’s Memory was formed, which was responsible for the “correct manufacture of busts, bas-reliefs and pictures” featuring the late leader’s likeness. Made by a few dozen sculptors in Moscow, busts and statues were shipped to every major city across the Soviet Union. Four years after the obelisk was erected, and a bust of Lenin assumed its position, accompanied by the famous propagandistic phrase: “Five-year plan in four years!”

But Lenin’s bust stood only for a few years before the square was converted into an intersection for carriage and automobile traffic. As Stalin consolidated power throughout the 1930s, he began ordering the construction of sculptures of himself to enhance his own cult of personality. In 1947, the Uzbek State Planning Agency once again erected a monument in Revolution Square, this time with a statue of Stalin, which stood for fourteen years.

In 1961, 22nd Congress of the Communist Party was held, and the governing body attacked Stalin’s cult of personality and advocated for the erasure of his figurative sculptures. Tashkent’s statue of Stalin was destroyed and the remaining pedestal was inscribed with the new party platform in both Russian and Uzbek languages.

Five years later, a devastating earthquake rocked central Tashkent that resulted in the destruction of the old city center, leaving 70,000 families homeless. As part of the reconstruction efforts, the areas around Revolution Square were dramatically refashioned, with Tashkent’s traditional architecture replaced by massive Soviet-style housing blocs and commercial buildings. Automobile and pedestrian traffic were oriented around the square, adding to the symbolic potential of the site. Within a year after the earthquake, city planners replaced the square’s stela with a monument to Karl Marx, which lasted until the fall of the Soviet Union.

In 1991, the newly independent Uzbek government dismantled the Marx bust, renamed the area Amir Timur Square, and constructed a large statue of the conqueror in its place. Since then, the state has utilized expended significant resources to make the monument more prominent, such as removing hundreds of trees that once provided a scenic backdrop for local cafes. This project, coupled with the construction of statues of Ali Shir Nava’i in the city center, indicates that the authorities have a continued interest in erecting and maintaining monuments in the public sphere.

Creating Uzbeks: Soviet Nation-building Projects in Central Asia

Although Uzbek authorities have clearly utilized monumental propaganda in the same manner as Soviet city planners, the new regime has consciously monumentalized figures that predate the Tsarist and Soviet period. In doing so, Uzbek political elites have facilitated the progression towards a new historical focus, one that would legitimate the new regime in a world organized into nation-states. Considered the fathers of an ethno-linguistically defined nation, Amir Timur and ‘Ali-Shir Nava’i have come to signify Uzbekistan’s return to “Uzbek” history—a perceived corrective to decades of imperial machinations. However, the political licensing of historical heroes as emblems of certain ethnic groups is itself a pattern that was introduced by Soviet scholarship and state planning.

Central Asian communities were not socially or politically organized by notions of ethnically-defined nationhood before the Soviet period. Instead, the region consisted of a collection of multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, and multi-religious societies generally administered by local principalities in urban areas and tribal confederations on the steppe lands. Following the Bolshevik Revolution, prominent party members contemplated new methods to consolidate power in the far-flung regions once ruled by the Tsar.

First, Bolshevik leaders created well-defined territorial units to be ascribed to specific national groups. This process, called razmezhevanie (national delimitation), identified nationality along ethnic and linguistic lines and created a full range of national institutions within each new territory, including writers’ unions, theaters, opera houses, and national language academies.

Secondly, In an attempt to demonstrate that it would not continue the chauvinist policies of its predecessors, the Bolshevik regime promoted local cadres to work in the administration of the non-Russian areas in the Soviet Union– a policy called korenizatsiya (nativization). Administrative institutions were required to work in local languages and to foster a state-sponsored intelligentsia that would specialize primarily in national history, literature, and language. However due to regional, cultural, and linguistic diversities, the process of nativization raised several dilemmas: What dialects will be selected as the official languages of administration? Which events and figures would be considered appropriate for inclusion in national historical narratives?

Fathers of the Uzbek Nation?

The newly constructed Uzbek SSR was previously an area of great linguistic diversity among the population. As Soviet historians and linguists concerned themselves with “ethno-genesis,” the concepts of diglossia, polyglotism, and language contact became problematic. In order to create distinction between groups, Soviet administrators chose standards that were considered “pure” and were not “spoiled” by other languages. In the case of the Uzbek language, the Soviet scholars traced the contemporary language’s origins back to ‘Ali-Shir Nava’i, and even proclaimed him the “Father of Uzbek Literature.” Interestingly, Nava’i wrote in the Chagatai language, an extinct Turkic language that is not a direct ancestor to Uzbek. The Uzbek SSR aimed to create a literary history that could compete with the longevity of Tajik-Persian, and officially renamed Chagatai “Old Uzbek,” greatly misrepresenting the relationship between the two languages in the process.

The central authorities disseminated material objects featuring representations of the poet throughout the Soviet Union. In 1941, Moscow appointed a multiethnic committee to arrange celebrations for the 500th anniversary of Nava’i. To correspond with the jubilee, the government built a new opera house and museum of literature in his name, and also issued commemorative statues, medallions, and postage stamps featuring images of the poet that would circulate across the republics. These celebrations (and the building projects associated with them) were repeated for the 525th and 550th anniversaries. As the material evidence demonstrates, the officials championed Nava’i as an “Uzbek” hero even up to the final days of the Soviet Union.

While Amir Timur himself was not celebrated by the Soviets, Timurid cultural objects underwent a “conversion to Uzbekhood.” Unlike the pastoral ancestors of the Uzbeks, the material evidence of Turco-Mongol rulers dotted the cityscapes of Uzbekistan because of the conqueror’s proclivity for building monumental architecture. The Soviets were keen on restoring Timurid structures and presenting them to the international community. As early as the 1950s, Uzbekistan was portrayed as “the cradle of cultured socialism” across Central Asia and the Timurid buildings were marketed as Soviet endorsements of cultural and ethnic diversity. In the post-independence period, the Timurid epoch is typically viewed as the “Golden Age” to which contemporary Uzbek statehood can be traced.

In addition to propagating material representations of Timur and Nava’i, the Karimov government continued the “Uzbekification” of these figures by rewriting political history and literary canons. Historiography produced by local Central Asian scholarship is heavily dependent on the state and state ideology, and thus reflects national interests, interstate relations, and leaders’ proclivities. In 1996, the Uzbek government continued Soviet-style commemorations by celebrating the 660th anniversary of the Timurid dynasty and opening a museum dedicated to the empire. Uzbek politicians and scholars have challenged the depiction of Timur as a ruthless conqueror, and instead perceive him a beneficent leader and patron of the arts.

Nava’i and his works also continue to play a large part in the state’s contemporary ideology. In addition to the building of statues and other material forms like the Nava’i National Park in central Tashkent, Uzbek authorities encouraged the publication and study of Nava’i works internationally, comparing the creative legacy of Nava’i to that of “a boundless ocean.”

Conclusion: A Radical Break?

By examining the turbulent history of 20th century monuments in Tashkent, one can see that the transformation of the public sphere in order to reflect changing political circumstances is not a new phenomenon. Thus, by focusing primarily on statuary, it is clear that contemporary Uzbekistan has not radically departed from the Soviet tradition. In fact, Uzbek monumental programs are a continuation of a legacy that displays state power in the public sphere, selectively appropriates historical figures, and reinforces soviet-era ethno-linguistic divisions.

Bibliography:

Cummings, Sally N. “Inscapes, Landscapes and Greyscapes: The Politics of Signification in Central Asia.” Europe-Asia Studies. no. 7 (2009): 1082-1093.

Dadabaev, Timur. “Power, Social Life, and Public Memory in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan.” Inner Asia. no. 12 (2010): 25-48.

Danzer, Alexander M. “Battlefields of Ethnic Symbols. Public Space and Post-Soviet Identity Formation from a Minority Perspective.” Europe-Asia Studies. no. 9 (2009): 1557–1577.

Fierman, William. “Uzbek Feelings of Ethnicity. A Study of Attitudes Expressed in Recent Uzbek Literature.” Cahiers du Monde russe et soviétique. no. 2/3 (1981): 187-229.

Forest, Benjamin, and Juliet Johnson. “Unraveling the Threads of History: Soviet-Era Monuments and Post-Soviet National Identity in Moscow.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers. no. 3 (2002): 524-547.

Kurzman, Charles. “Uzbekistan: the Invention of Nationalism in an Invented Nation.” Critique. no. 1 (1999): 77-98.

Slezkine, Yuri. “The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism.” Slavic Review. no. 2 (1994): 414-452.

Stronski, Paul. Tashkent: Forging a Soviet City, 1930–1966. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010.

3 comments