When it comes to Iranian films, there are a few familiar themes that enthusiasts might expect – love, revenge, war, religion, piety, class, gender, sexuality, family, and the nation. Curiously left out of these expected themes is the topic of race. In a post-Ferguson world, questions of race and blackness have become more central to daily discussions in the United States and the Middle East, even prompting calls for solidarity projects among marginalized peoples. As tensions between race and the nation-state are increasingly reflected in daily discourse, how might this friction register in an Iranian context?

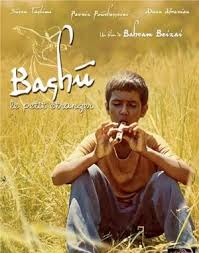

Named “Best Iranian Film of All Time” by an Iranian magazine in November 1999, Bahram Beizai released a groundbreaking film entitled, Bashu, the Little Stranger (1986) (Bashu, Gharibe-i Koochak). Set during the Iran-Iraq War, the film follows a young Afro-Iranian boy, Bashu, who flees ahead of the devastation wreaked upon his southern Iranian village by the Iraqi invasion. His journey brings him to Gilan, a northern province where Gilaki is predominantly spoken. Upon arriving in Gilan alone, Bashu meets two village children and their mother, Nai’i, who shelters and cares for him. Throughout the film, Bashu and Nai’i attempt to negotiate Bashu’s place, not only within Nai’i’s family structure, but also within the Gilani village.

Through Bashu’s attempts to assimilate into a village where his dark skinned features and Khuzestani Arabic denotes his displacement, Beizai’s film prompts criticisms of ethnocentric Persian nationalism and questions the experience of blackness in Iran, while neatly underscoring the tension between nationalism and gender. Bashu’s struggle in this context illustrates more complex intersecting issues of race, ethnicity, gender, and nation in the Iranian context.

Bashu was completed during the Iran-Iraq War, a period in Iranian cinematic history that experienced increased control by Islamic hardliners. Beizai’s film was delayed until 1988 due to certain ‘problematic’ scenes. Bashu explores a variety of tropes and ideas, ranging from patriarchal familial roles to ethnocentric nationalism, which in many ways undermined the very foundation of Iranian cinema standards set by the Islamic Republic at that time. While previous scholars have analyzed the film in terms of gender, film technologies, and nationalism, this article centers blackness as it is depicted in the film while acknowledging the role of intersecting identities. The confluence of these identities such as gender, race, class, and nation mutually construct each other and reveal a new element in Beizai’s film, showing us how blackness in particular complicates social hierarchies.

A Journey from Khuzestan to Gilan: Bashu’s Story

When he reaches Gilan, Bashu encounters Nai’i’s family who, startled, cannot grasp Bashu’s existence and asks, “why are you so dark?” Stunned by Bashu’s lack of response, Nai’i comments that he might be a jinn, or a type of spirit, and that he is black and dumb. In contrast to Bashu and Nai’i’s language barrier, she has no problem speaking with farm animals, which we see after Bashu explains his situation in Khuzestani Arabic. Aside from language, Bashu’s very skin color is incomprehensible to Nai’i and the Gilani villagers. Frequently compared to charcoal, called a thief and ill-bearing omen, they attempt to scrub away his blackness and turn him clean – white.

Bashu’s intelligence and humanity is only understood after being assaulted by local village boys. One of the kids punches him to the ground and Bashu faces two choices: a rock and a book. He grabs the book and reads an iconic and nationalist Persian line: “we are the children of Iran, Iran is our country.” Through Persian, Bashu is able to open a space for his existence in the village. Later, when Nai’i’s husband returns from war, a similar scenario of Persian as a medium for negotiations takes place. Despite this particular event, his blackness continues to demarcate him as Other, as village boys mock Bashu when he sings in his native tongue and performs a ritualistic dance.

It is clear that racial difference is not the only way his ‘Otherness’ is understood. Bashu’s journey is complicated by linguistic differences. Persian was standardized as the official language of Iran in 1935. Persian became the predominant method through which educated Iranians (typically men) of diverse ethnicities could communicate with each other.

The standardization of Persian coincided with a dramatic increase in ethnocentric Persian nationalism, characterized by an increase in the ostracization of Arab culture and language, as well as all others deviating from the new Persian norms. In the case of Beizai’s narrative, this ethnocentric nationalistic standardization had another consequence as well; the state language held little worth in villages and often barred women from a place of power within the nation-state structure. An examination of mutually constructing identities, or intersectionality, is essential for understanding interlocking issues of blackness, ethnicity, gender, and nation.

“Why are you so dark?”

Intersectionality as popularized by Black feminist scholar and activist Patricia Hill-Collins, “examines how [gender, race, class, and nation] mutually construct one another”, as opposed to assessing them as distinctive social hierarchies. Throughout the film, Bashu’s identity as a dark-skinned foreigner is constantly challenged, forcing him to re-articulate his existence in alternative ways. Blackness is the first and dominant mechanism for contention in Beizai’s film. Additionally, his Khuzestani Arabic acts as a signifier of otherness, which further ostracizes him from the Gilaki speaking people of Gilan.

On the other hand, Nai’i’s identity as a woman in a patriarchal-dominated society forms another piece to Beizai’s film. Although Nai’i is portrayed as complicit in reifying structures of whiteness that vilify blackness, it is impossible to see only her “whiteness”, but examine her situation as enmeshed in gender, class, language, and the nation. Mutually constructed identities are crucial to Beizai’s film because each inform and influence the next, especially as Bashu attempts to negotiate his ‘home’ in Nai’i’s family and village, which makes Hill-Collins’ work a useful entry point for discussing Beizai’s work.

In the first encounter between Bashu and Nai’i, she is suspicious of his blackness and questions, “why are you black?”, as though blackness was not a permanent state, but an affliction of sorts. From this interaction, one immediately gathers that black is not a desired state of being, nor characteristic of “normal” in Gilan. This notion of blackness in the Gilani village is further reinforced by villagers – his blackness is constantly referred to as an affliction, stupidity, sickness, uncleanliness, bad omens, thievery, and demons and spirits. Within the Iranian context, this is not the first case of blackness being linked to otherworldliness or having ‘magical’ properties. In fact, within Iranian folklore, blackness is canonized in the form of Haji Firuz, a figure known for appearing every Persian New Year to wish good tidings for the upcoming year. Typically, the costume is donned by wearing blackface. Therefore, when a village child strokes Bashu’s face to see if his blackness smudges, one could wonder if she was expecting a Haji Firuz character. Even Nai’i is complicit in upholding this type of belief system – she tosses Bashu in a river and vigorously attempts to scrub away his “charcoal layer” to reveal a fairer skin – and illustrates the constructed binary which places blackness as dirty and whiteness as clean.

But what does this criticism of Iranians’ view of blackness communicate, besides revealing “inherently” racist beliefs? If we consider the tenets of intersectionality, Beizai’s focus on blackness confronts an ethnocentric Persian nationalist narrative that equates white Persian with an imaginary of the Iranian nation state, a narrative that disregards the multiple ethnicities that populate Iran and permits the marginalization and erasure of ethnic populations. Furthermore, instead of treating difference as a simple regional issue, he centers blackness in a key way to emphasize race. Finally, he shows how ‘Iranian-ness’ varies – not only in terms of ethnicity, but also languages, as the film is primarily in Gilaki and Khuzestani Arabic, with sparse use of Persian. Even during the showing of the film, it lacked Persian subtitles.

“We are the children of Iran, Iran is our country”

Beizai’s decision to create an Iranian film set in a northern Gilani village and use Gilaki, a dialect close to Persian, carries two significant criticisms. First, as Nasrin Rahimieh notes in “Marking Gender and Difference in the Myth of the Nation”, the geographical displacement and subsequent introduction and centering of ethnic differences in a presumed homogenous Iran, “helps to problematize the myth of a linguistically, racially, and culturally unified Iran” (Rahimieh, 262). The quick linguistic shift from Persian to Gilaki enables language itself to act as an agent of displacement and forces the exclusively-Persian speaker into the position of struggling to understand the dispersed idiomatic phrases and expressions that share some commonality with Persian, but are nevertheless mostly incomprehensible. Effectively, Beizai’s techniques serve to turn the viewers into ‘Bashu’ and experience his displacement with him.

Secondly, Beizai’s film illustrates that Bahsu’s existence can only be legitimated through the framework of the nation-state. After his initial confrontation with village boys, in which he reads an iconic, nationalist line in Persian, “We are the children of Iran, Iran is our country,” his existence becomes recognized. Most people in Iran learn Persian in school, thus Bashu’s ability to read and speak Persian signified that he was educated. This act authenticated his intelligence, as his blackness previously signaled the lack thereof, to the surrounding villagers. Taking the initial viewing audience in Iran, it is first through this line that they recognize Bashu’s Iranian identity. Such an interaction, where Persian is the medium through which belonging is communicated, isn’t an uncommon event, especially as one travels within Iran. Thus, Beizai stealthily critiques the presumed Iranian viewer for identifying with the villagers and an assumed ethnocentric Persian understanding of what “Iranian” means.

An intersectional approach illustrates that blackness complicates these neat and simple narratives of Iranian nationalism, especially when a character such as Bashu at once fits into the structure of Persian-speaking Iranian, but doesn’t because of his blackness and native tongue – Khuzestani Arabic.

Bashu stands as a simple story of a displaced orphan’s attempt to find safety, ultimately within a Gilani family. The beautiful shots of northern Iran are breathtaking and surely inspired wanderlust for many. Expertly placing the film within the trend of Iranian films of the time, Beizai’s film flexes both a humanist and a critical approach. If one thing is for certain, Beizai positively shocked his predominantly Persian-speaking audience with Bashu. Within the folds of Bashu’s narrative is a complex and thought-provoking tension between interlocking identities, and questions of race, gender, class, and nation.

Similar to Bashu’s attempt to assert himself within the Gilani village, these identities are shown to assert themselves within particular contexts, one often dominating and influencing another. Through the frame of intersectionality, we can observe how Bashu’s blackness intervenes on his place within the nation-state, as he does not ‘fit’ the ethnocentric Persian stereotype of Iranian. Constantly, his blackness – once displaced from the south of Iran – becomes a point of reference for his being and Otherness. Reflexively, we observe that blackness fractures the assumingly neat ethnocentric Persian nationalist narrative, demonstrating black bodies cannot be equivocally excluded as not Iranian. Moreover, language demonstrates that Persian, while the official language of Iran, does not characterize all Iranians – both in terms of ethnicity and gender. Bashu exceptionally tangles with these complicated issues with such subtlety, that each viewing reveals yet another layer of Beizai’s intellect – fitting for the “Best Iranian Film of All Time.”

3 comments

Thanks for the great post. BTW speaking of black Iranians, Hamid Saeid is an interesting and popular personality. Take a look here: http://theotheriran.com/tag/hamid-saeid/

Great article just in need of a correction. The Gilaki language is neither a dialect of nor close to Persian. It actually belongs to an entirely different language family namely the Northwestern branch of Iranian languages where as Persian is a Southwestern Iranian language. In this sense, Gilaki could be said to be closer to other Caspian languages such as Mazandarani or even other Northwestern Iraninan languages such as Kurdish rather than Persian.