This article originally appeared in the 2015 edition of Tirgan Magazine, as part of its segment on “artifacts”. This is the official magazine of the biannual Tirgan festival based in Toronto. This festival celebrates Iranian art and culture from within Iran and across the global Iranian diaspora, and is the largest of its kind outside of Iran. Other entries from Trigan Magazine are available here.

“Artifacts” are cultural condensation. They are the objects that put into relief a certain way of life, identity, historical period, social entanglement, etc. Just like “keywords”, they offer a great way to glimpse a bigger picture.

Fardin Alikhah earned his Ph.D. in sociology from Allameh Tabatabaei University (Tehran). He is currently a faculty member of the Department of Social Sciences, Humanities and Literature at Guilan University. His research focuses on the politics and social dimensions of mass media. His scholarly writings appear in both English and Persian.

In the early 1990s, everyday conversation in Iran was animated with much talk about a new kind of technology. Like turning the knob on a radio in search of stations, and just as easily, it allowed for tuning into TV programs from beyond Iran. The Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988) had recently ended, and the turmoil of war had begun to subside. This technology was the satellite dish, and it was cause for excitement. At first, these dishes were over a meter wide. There were few people who could both afford them and had the necessary space to install them. And just like the introduction of television in Iran, the relatives and friends of these early adopters would gather in their houses to watch its programs.

These dishes continued to shrink in size, while their receivers grew in affordability. As a result, more people were able to use them. In those days, the receivers were analog and only offered about forty channels, mostly Arabic and European. This content wasn’t especially appealing and none of the broadcasters were particularly popular, but Iranians were enthused nonetheless. With the war over, they could watch TV any time of day, without interruption, without requiring to, and without being limited to government programing. And so their usage expanded, and these dishes were increasingly visible from the streets.

Eventually, the use of satellite dishes became a matter of contention in Iranian mass media. A public conversation ensued: ‘just what is this new technology and what implications do it has for our society?’ It had its detractors and its protagonists, and they had their reasons. Finally, in 1994, it was a conservative-led Parliament that banned their use. The government asked people to voluntarily hand over their receivers to the police. Some complied, but others chose to tuck away their dishes and receivers until the controversy died down. A few months passed and satellite dishes were once again a fixture on the rooftops, only this time they were covered with sheets.

The satellite dish made a significant impression on Iranian society in those years. It was an accessible window into other worlds. Iranians could glimpse the social lives of other peoples through its programs; learn of the latest consumer goods through its advertisements; and follow life-style channels. On the whole, the satellite dish helped cultivate a more aesthetic sensibility toward everyday life; which was not tenable while the war was going on. In many ways, it enabled conceptions of self to shift from being rooted in faith to being rooted in consumption.

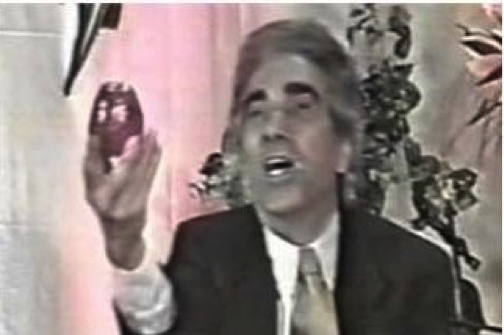

A milestone came in 1999 when viewers tuned into the first Persian-language satellite channel, NITV. It came from abroad. This was such an uncanny affair that even its own producers seemed to require convincing. On one occasion, when a viewer in Isfahan called into one of its shows, the anchor held up a prop-fruit and asked him to confirm what kind it was.

Opposition groups abroad were quick to realize the potential of this technology for directly communicating with Iranians. In the first five years following this milestone, Persian-language broadcasters proliferated; mostly led by such opposition groups abroad. A discourse of excitement emanating from outside the country inundated Iranian airwaves, and met with a locally produced discourse of fear and anxiety.

In those years their programming was only studio-based talk shows. A host—usually also the owner of the network—would receive calls from viewers. It was common to hear the phrase “Hello you’re on the air!” (using the English word for “air”). TV, in other words, was functioning like radio with visual aid. Such content eventually grew repetitive and tired.

Soon Western governments also began broadcasting. The American government launched a Persian version of Voice of America, and the British did the same with BBC Persian. By this point there was so much programming to choose from that users begin compiling them into “favorite channels”, and ignoring the rest.

Then came another milestone: the launch of PMC, the first professionally produced Iranian music channel. Entertainment programming took on a new dimension, and beginning in 2005 amateurishly produced channels were sidelined. Better programming stirred the excitement of audiences once again, and expanded their tastes. Among such Persian networks were BBC Persian for news, Manoto for general entertainment, and Farsi 1 for dubbed TV serials. Together they evolved Iranian satellite TVs, and since 2010 standards of production have been more polished than ever.

Eventually there emerged giants in this diverse landscape looking to satisfy the ever-growing tastes of Iranian audiences. The GEM group of channels is worth noting…Their programming has partly had the effect of ‘depoliticizing’ television for family audiences, especially since the political turmoil of 2009.

This cultural bent of mass media in Iran has come in phases. Back when videotape players were common, for example, it was Indian films that were popular. With the coming of satellite television, this cultural content has gone through Arabic, European and American waves. Today it’s Turkish serials that are popular…and even working to draw Iranian tourists to Turkey.

It’s fair to say that all segments of Iranian today are more or less tuned into satellite TV. Signal receivers (LNB) continue to rotate on the rooftops. One day they turn toward Yahasat, the next toward Eutelsat, and the day after toward Turksata (various satellite networks). Will they ever turn toward ‘home-grown’ content?