Emerging Scholarship is a series showcasing the research and interests of new voices emerging from academia that focus on the social worlds, histories, and traveling cultures of Central and West Asia.

Narges Bajoghli is a PhD candidate in Sociocultural Anthropology at New York University and a documentary filmmaker in NYU’s Culture and Media Program. Narges’ research focuses on pro-regime cultural producers in Iran. Her dissertation is entitled: “Paramilitary Media: Revolution, War, and the Making of the Islamic Republic of Iran.” She is the co-founder of the non-profit organization, Iranian Alliances Across Borders (IAAB). She is also a co-organizer for “Animating the archive: A Series of Symposia on Iranian Cultural History,” which will be held at NYU from October 2015 to March 2016.

Narges is the director of The Skin That Burns, a documentary film about survivors of chemical warfare in Iran, distributed by Film Media Group. The film has screened in The Hague, Hiroshima, Jaipur, Tehran, and in the U.S. (New York, New Orleans, New Jersey, Chicago, and Irvine), at festivals and university campuses.

1) Ajam: Hello, and welcome to another installment of Ajam Media Collective’s Emerging Scholarship Series. I’m Rustin Zarkar, and today I’m here with Narges Bajoghli, a PhD candidate at New York University’s Department of Anthropology. It’s a pleasure to have you. So today is the anniversary of the Iran-Iraq War. It is September 22nd and it’s been thirty-five years since the start of the conflict, so this is a very timely interview. Narges, your research is specifically about paramilitary narratives of the Iran-Iraq War in contemporary film. Could you give a brief introduction to these paramilitary organizations and their role during (and after) the Iran-Iraq War?

NB: Sure, I focus on various paramilitary organizations, but the main one is the Basij, which was created at the very beginning of the Iran-Iraq War. When Iraq invaded Iran in September 1980, the newly-established Islamic Republic was facing a big problem in which it was being attacked by a very sophisticated army while its own army was in disarray. They had eliminated a lot of the high generals and commanders of the Iranian Army in order to be able to stave off any potential coups that Ayatollah Khomeini thought could happen following the Revolution. So, in trying to figure out how to counter the Iraqi offensive, Khomeini made a call for an army of 20 million and this is the origin of the Basij.

It was a volunteer effort, later consisting of young men and boys, which was mobilized with the aim of overwhelming the Iraqi military with sheer human numbers. The idea of the Iranian political elite at the time was that we may not have the sophisticated weaponry to fight the Iraqis, but we do have a higher population that can be incorporated into a military strategy.

My own research is about the history of the Basij, and how the Basij and the Revolutionary Guards were instrumental in creating media at the time of the War for recruitment purposes, and for creating a narrative about the Islamic Republic as an institution where ideas of Shi’i heroism could be established. However, I am most interested in how these narratives of the War begin to reformulate themselves in the current period, given the fact that Iran’s population is predominantly under the age of 35. Young Iranians don’t remember the War or the Revolution very well at all.

The Iran-Iraq War is the ideal moment for the Islamic Republic, and not the Revolution itself because there were so many contending ideologies and groups in 1978-1979. The Iran-Iraq War is a moment when the Islamic Republic can say, “Our soldiers showed their heroism,” but how does the Islamic Republic go about representing this period to a younger generation in order to keep the Islamic Republic alive into the future? I am looking at how paramilitary organizations like the Revolutionary Guards and the Basij, were able to use significant resources for media production, especially during and after the 2000s when they became independently wealthy.

One of the ways these organizations could communicate with the younger generation was through media. Most young people around the world and in Iran consume different forms of media: television, films, video games, etc. The Revolutionary Guard and the Basij thought that if they were to get their message across to young people, they would not only have to engage more and more with media, but they would have to divorce themselves from what they thought was the propaganda of the 1980s and early 1990s.

Throughout the interviews I conducted, Basij members repeatedly said that they view the cultural products produced in the 1980s as propaganda, since it was aimed at recruitment. But now they believe they have to produce something different. So I started looking at how these different organizations used their economic power to try to create something that was more effective at communicating with younger generations.

2) Ajam: Fascinating, so there is an element of the “truth of war” versus the official narrative that was considered more propaganda-oriented. A follow-up question to this is why are these narratives important and what do they intend to convey? Why is documenting the War so significant for the Islamic Republic and what role do paramilitary organizations play in this project?

NB: The Iran-Iraq War plays a very fundamental role for military and paramilitary organizations in Iran. The very first reason is because it was such a long war–it lasted eight years. Many of the men who volunteered or were recruited spent the majority of their young lives at the war front. I want to be clear that the experiences of Iran-Iraq War veterans were not fundamentally different from veterans in other wars. If you read literature from any sort of war around the world, there is something about the horrific experiences of close combat that leaves a trace on those who participated in it. The Iran-Iraq War is no different.

This constant close proximity to Iraqi soldiers shaped the way Iranian veterans view what happened. These feelings were compounded by a sense of alienation when they returned home. Iranian wartime and post-war society was dominated by the official discourse of these veterans and heroes, but many people were growing tired of eight years of this narrative. The civilian population stopped engaging with it, and began to look the other way.

So veteran cultural producers began to despise the official version of the war. They realized that this discourse was used to advance certain political narratives with which they themselves were not in agreement. In response, many veterans attempted to create different narratives of what the War was about. And the more in which they were able to find the financial resources, the more they tried to do that.

When I started this research eight years ago, I always thought the War narrative was monolithic. However, the more I dug into it, the more I realized that it is actually not the case at all. Not all veterans agree with the official version of the war. Many heavily disagree with one another about its representation.Veterans that do disagree sometimes cannot speak out for various reasons.

For example, many get financial assistance from the Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs for medical treatment for the injuries that have received during the war, so they can’t afford to be too critical in public about these things. Others, however, are more willing to do so. What I find really interesting about narratives of the war in their contemporary form is that it is more than just the history of the 1980s, but more so, they are more about the desires that certain regime supporters have about the future of the Islamic Republic itself.

3) Ajam: Yeah, I think it is important to mention to our listeners that cultural production about the war is visible throughout the Iranian public sphere. Our own articles on Ajam have shown how municipal authorities have a vested interest in commissioning murals and sculptures for the commemoration of fallen martyrs and veterans. There’s also the Holy Defense Museum in Tehran. Similarly, there’s been recent scholarship about the representations of war in Persian works of fiction, printed both in and outside of Iran. But what is so significant about film as a medium?

NB: Cultural production about the War is very prevalent today. But where does the funding for this cultural production come from? Who is behind each of these projects? I think this reveals in some ways the intention of creating one narrative over another. For example, there was a very big fight between the former Ahmadinejad administration and Qalibaf (the Mayor of Tehran) about the funding for the Sacred Defense Museum. which opened its doors in late 2012, that actually stalled the construction of the museum for many years. Very similarly, there was a lot of fighting between them in order to open up the Tehran Peace Museum. And the reason this is significant is because the people behind Ahmadinejad have a very different understanding and thought process about what the war should mean for Iranian society, versus those who support Qalibaf.

Cultural production about the War may seem like it is very rampant in Iranian society, but once you begin to look at the details, you actually see a lot of the factionalism (which we read about in Iranian politics) play out about the War.

I chose to focus on cinema for a couple of reasons: feature films and documentaries have different funding structures. For feature films, especially big cinematic productions, there is a lot of money needed. As I mentioned before, both the Guards and the Basij became independently wealthy in the 1990s in Iran, and were then able to pour that money into media production.

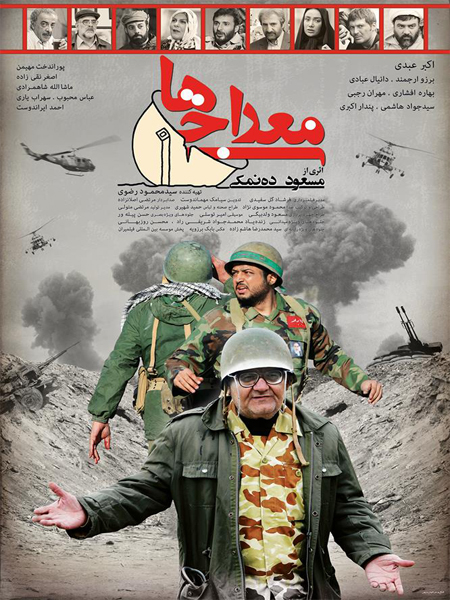

The directors and producers of these films, like Masoud Dehnamaki for example, get a lot of money through private banks that are controlled by the Revolutionary Guards. For me, looking at these films is a way of tracing the political economy of how these military institutions have risen in Iran. Regarding documentaries, they tend to have a lower budget than feature films do. You see “independent” veterans taking up cameras with very small crews.

Why are they making these sorts of contributions? Before the Revolution (but more so after), Iran became well known for its film industry. However, most of what has been written about the Iranian film industry has been about the avant-garde filmmakers like Abbas Kiarostami. I think they are important, but Kiarostami and Jafar Panahi’s films are not allowed to be featured in theaters in Iran, and if they are, they are only shown for a couple of weeks. But people really engage much more with popular films. In the past decade or so, there have been a lot of films breaking box office records that have war as a central theme. A lot of film critics dismiss these films by saying that they are cheap and people don’t understand what they are watching.

I wanted to push a little behind that and ask why is it that there are so many people who go out and watch these sorts of film. What is it that draws them to these films? What are the strategies that the film directors and producers are using to draw more people? In the 1990s, attendance to war films were at an all-time low — no one was going to watch them. Members of paramilitary organizations actually sat down and discussed different strategies both for film-making and editing, and even on the distribution end. They wanted understand what could draw more audiences in.

4) Ajam: Since the Iran-Iraq War enterprise is so large, can we assume that there are different genres? What types of categories have you encountered in your research?

NB: There are feature films, documentary films, there are television-series films, there are also films made underground, which are distributed and watched among the veterans only. These underground films are extremely critical of what is going on in the country. Though these types of films are categorized as war films, these pro-regime filmmakers and cultural producers are making films that are not just about the war anymore.

They are making films about opposition groups in and outside of Iran against the Iranian state. They are making films about the different religious and military commanders who they think are “more moderate” and therefore can appeal to younger audiences.

There has been television documentaries and films made about Imam Musa Sadr, the Iranian-Lebanese Shia cleric in the late 1970s who lived in Lebanon. There’s also a film about Mostafa Chamran, a commander who was killed at the beginning of the war. Even though these all fall into the wider genre of Iran-Iraq war films, they do not really even touch on that period anymore. They are just kind of seen as new topics that need to be explored from the perspective of these pro-regime cultural producers in order to get young people back into the Islamic Republic.

Most people have not talked about underground films. These underground films are made by veterans and tend to circulate among other veterans. They explore the horrible state of veterans who have been exposed to chemical warfare, those that are completely paralyzed, veterans who have had their limbs blown off by mines. Very importantly, they show people who are now in mental institutions— veterans that the state does not talk about very much at all.

There have been some veteran filmmakers who have gone to these hospitals and made films in order to raise awareness of how the bonyad-e shahid or the Martyr’s Foundation is failing them. It’s really a critique of the Islamic Republic. In a sense they are saying, “[the State] uses us every single year to say our martyrs and soldiers fought for the freedom of Iran and every single year there are holidays, and yet look at how they treat us.” This is really a sort of meta critique in some ways, of the Islamic Republic itself.

5) Ajam: In Iran, the Iran-Iraq War is commonly referred to as “Defa’-e Moqadas” or the Holy Defense. From the moniker, it is clear that the conflict took on a religious dimension and was framed by the early ideology of the Islamic Republic. In what way, if any, has the wartime religious cosmology been reproduced in these films?

NB: So in the early films this was kind of reproduced to a “T.” It was very much reproduced as these soldiers that were driven to emulate [the 3rd Shi’a] Imam Husayn, and that’s why they went to the war front. But in later years this began to change because a lot of the filmmakers began to realize that young people were not responding to these films, and they wanted to show that not everyone who went to the front was a pure angel. You begin to see traces of this development from the early 1990s, as filmmakers began to show individuals who were afraid to go to the front, or those who are not as brave.

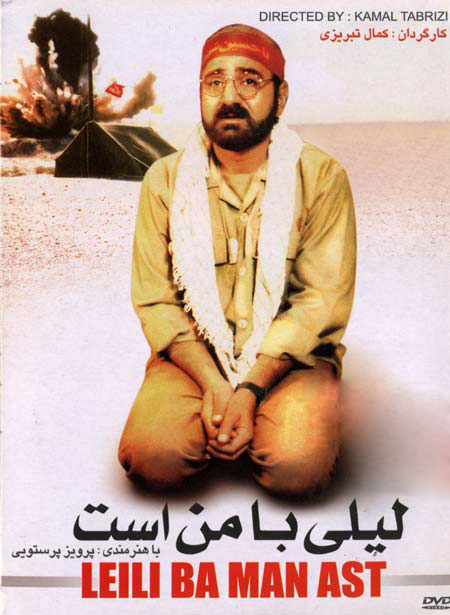

You see this in films from the middle of the 1990s, like Leili Ba Man Ast (Leili Is With Me, 1996). It reaches a height with Dehnamaki’s latest films, like Ekhrajiha (The Outcasts, 2007). The filmmakers say that they want to show a different kind of soldier because they wanted to communicate hat you don’t have to feel like a hero to defend your nation. And this was coming at a time in which there was a heightened threat from the United States–where there could be a potential war.

A lot of these veterans-turned-filmmakers wanted to communicate that you could any point become Husayn or Yazid. They began to creating films that had “questionable characters” who became heroes on the front. So that’s one of the strategies that has taken place, but also what I think is really important is that when you talk to veterans themselves, so as you very rightly point out about the notion of the Holy Defense in Iran is played all out through murals, museums.

But when you talk to veterans themselves, almost without fail, they say there used to be books by [Persian poets like] Hafez and Sa’di, that had nothing to do with religion, and they used to read them together at the front. These books and experiences are never represented at the martyr’s museums or in mega-narrative of the War. I think it is important for those who do research on contemporary Iran and the Islamic Republic to begin to unearth some of these narratives, and not just take for granted what the Islamic Republic produced about the war.

Unfortunately a lot of literature that has been produced about the war and war culture in Iran are using sources from the Islamic Republic itself. I think we need to start speaking with the veterans themselves and really try to understand what is not written from the perspective of the Islamic Republic. It is also a form of power play: the various institutions of the Islamic Republic produce narratives about the War to serve specific purposes. So for us academics, taking those at face value is problematic.

6) Ajam: From my own experience, I have found that many policy-oriented discussions about the paramilitary organizations like the Basij seem to assume that the groups completely tow the line of the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. What do these underground films reveal to us? Is there any room for counter-discourses about the war?

NB: I think one of the main things that I found in my research is that the Basij, the Revolutionary Guards, and the Ansar-e Hezbollah (which is another Iranian paramilitary organization), by no means simply tow the line of the Supreme leader and they are by no means purely monolithic institutions. If we are willing to accept the fact that there is so much factionalism in the Islamic Republic itself, I don’t understand why we can’t see that sort of factionalism in the Basij, Revolutionary Guards, and Ansar-e Hezbollah in Iran.

In some ways, I think we are all caught up in this U.S. and Western policy understanding of these military and paramilitary organizations in Iran. We sort of build these monsters out of them, and we think what the commander says at the top gets followed all the way down the line. But if you actually go in the Basij and look at the different ways in which the Basij groups function in different cultural institutions–at the universities, at work spaces, in big cities, in small towns–they all function very differently from one another.

Now that does not mean that they do not have certain guidelines that they believe in, nor does it mean that there are no red lines that can not be crossed, but it does mean that there’s a lot of gray area in which they are allowed to function. In many cases they heavily disagree with and dislike one another, and in some ways they work in complete silence from one another. The ultimate red line is the belief in the Velayat-e Faqih (the Rule of Jurisprudence in the Islamic Republic), but in between that there’s a lot of debate and discussion.

Some of these underground films, in addition to the public films, show that there is a lot of counter-discourses about the war. I think if we choose to turn a blind eye to that simply due to the person’s politics, we are doing ourselves a disservice because we are not engaging with very real criticism. Criticism coming from veterans is tolerated in some respect by the local establishment because they hold the right cards, so to speak: They fought. If I were to come out and say something, I would not be tolerated as well as as someone who has been very much engaged with the political process of the Islamic Republic.

The Skin That Burns – Trailer from Narges Bajoghli

7) Ajam: Narges, in addition to being a brilliant scholar, you are also an accomplished filmmaker. You directed and edited The Skin That Burns, a 2012 documentary about volunteer soldiers who were exposed to chemical weapons during the Iran-Iraq War. Could you briefly explain the premise of the film and how it related to Basij networks you came into contact with as well as Basij-produced films?

NB: The first introduction that I had into those who were pro-regime came in about 2004-2005 when I was living and working in Iran. I was working on a project that was connecting different NGOs across the country in order to be able to respond better to things like the 2003 Bam earthquake that had just happened a year earlier.

As I was going around the country linking up different NGOs, I was introduced to an NGO that was in charge of caring for victims of chemical warfare. I had heard something about this in the past, but I had never really looked at it at all. At that point I was very allergic to anything that had to do with the War because of precisely due to the very monolithic narrative of the state. But when I began to meet these veterans and doctors who were working with the survivors, I started to see a different side to those who were pro-regime as well as those who had fought in the war.

For about four or five years, I did different work for this organization, and I traveled to the Kurdish parts of Iran which were the civilian parts most bombarded by Iraqi forces with chemical warfare. I got involved in an oral history project with these veterans and civilian survivors of this warfare, because the doctors were realizing that, after about 20-25 years of exposure, many of these survivors were developing various forms of cancer and were dying. The oral history project would keep a lot of their memories alive, particularly about what had happened and what they were going through medically. I met different veterans and civilians and I really thought that this was a story that needed to be told to those less knowledgeable.

One of people I met, Ahmad Salimi, really stuck with me, who is the main protagonist of the film. What I loved about Ahmad was that he was a veteran that used different methods to cope with what had happened to him. Up to this point he had lost his vision in one eye, and could only see light in the other. His lungs were collapsing and he was on the wait list for a lung transplant. His skin had been burnt. He used music as a form of therapy.

This was something that I was seeing more and more with a lot of the veterans: the creative ways in which the were coping with the PTSD they were going through, as well as the various other medical issues. Again, these were stories that was completely erased in official narratives of the war. Iranian television crews would come and interview Salimi, but they would insist that he wouldn’t mention that he plays his music, because they couldn’t really show it on the air. For me, it was really important to show this veteran who lived life differently from the way the Islamic Republic depicted him.

In 2011, I started to do research for the film and I went to Iran in 2012 to shoot the film. Really it was my attempt of showing the everyday lives of people who live with war even though it ended 25 years ago, and the way in which the war lives on in society– after the headlines are gone, after the cameras are gone, after the journalists were gone, and people were alone.

Most people don’t even remember the Iran-Iraq War outside of Iran and Iraq, and Iraq has already been through two or three other devastating wars since then. This was really an attempt at showing the long term effects of the war, and the very different and creative ways in which people cope with the after effects.

Ajam: Narges, unfortunately that’s all the time we have today. I think both your research project and your film are important ways for us to reflect on the Iran-Iraq War. I want to thank you for joining us today.

2 comments