In contemporary Istanbul, it can be quite difficult to find evidence of the city’s cosmopolitan past. While the vast majority of the city’s inhabitants today identify as Muslim, in the early 20th century the city’s population was majority non-Muslim. Among the many communities that formed part of Istanbul’s elaborate multi-religious and multi-cultural mosaic were large numbers of Ottoman Greeks, Armenians, and Jews who had been an indelible part of life in Istanbul – and across the Empire – for as long as the city had existed.

But ensuing historical events over the last century, such as the Armenian genocide, the Greek-Turkish population exchange, the pogroms of the 1950s, and various Turkification campaigns have contributed to the dwindling of these groups’ presence in the city. In addition, massive internal migration has meant that the city’s population went from under one million in the 1920s, to over 14 million today, the vast majority of whom are Turks or Kurds from across Anatolia of Sunni Muslim or Alevi background. At this point, the combined non-Muslim population amounts to about 1% of the city’s inhabitants, mostly concentrated in a few historic neighborhoods where they once predominated.

While history books, archives, and an aging generation of people who remember the past can serve as reminders of this era, sometimes the feeling of such a radically different city is hard to capture. Scholars have explored the gradual disappearance of cosmopolitanism in modern Istanbul in works like Streets of Memory: Landscape, Tolerance, and National Identity in Istanbul and Jewish Life in Twenty-First-Century Turkey. Additionally, recent generations in Turkey have shown increasing interest in exploring the city’s diverse past. Luckily, the prolific recording industry of the city and its diaspora offers another glimpse of how Istanbul once sounded through the traces of its musical legacy.

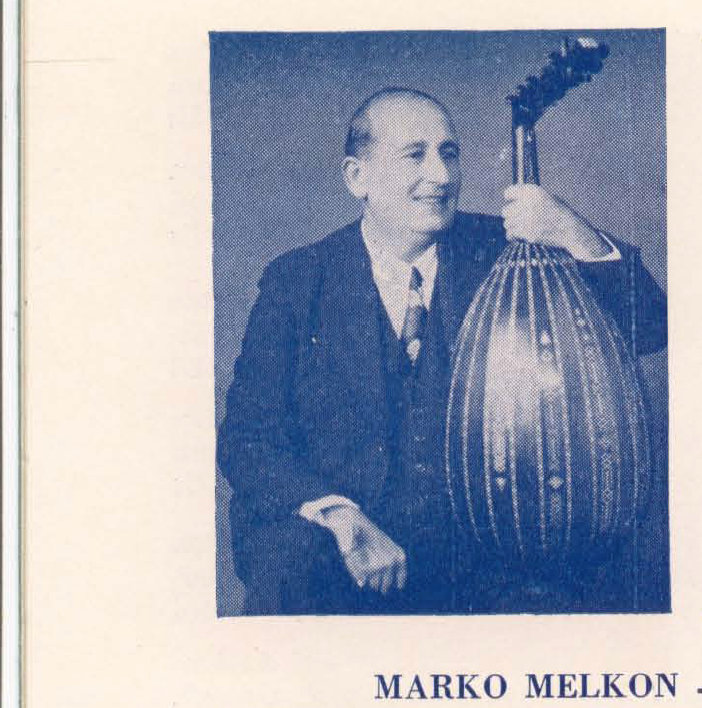

One such song was recorded by Marko Melkon in America in the late 1930s. Melkon was an Armenian singer born in Izmir (known by its Greek name Smyrna at the time) who fled the Ottoman Empire for Athens, Greece when the Turkish army began to draft non-Muslims in 1912. From Greece, he immigrated to New York City and made a career for himself as a musician in the United States playing the music of the Ottoman diaspora. As an Armenian from the Ottoman Empire, Marko spoke Armenian, Turkish, and also Greek due to his upbringing in Smyrna. He sang in all three languages, although his most prominent songs were in Turkish.

Marko’s style of music is referred to as the “kef” style, meant to be enjoyed at parties for dancing and general merriment. Although kef style songs exist in the various languages of the urban Ottoman populations of the time, the majority of songs in the kef style were in Turkish, as it was the lingua franca of the region and in turn, the nightclub scene. With the increase in the Armenian population in the United States after the Armenian genocide, the style continued to be played and also evolve, as it took on influences from other cultures and incorporated new instruments and compositions.

In one such song, linked below, Melkon gives the listener a sample of the many languages spoken in Istanbul at the time with the song “Galata’da Todoraki”:

The song is quite simple: the narrator asks his listener to head to the Galata neighborhood in Istanbul with him, in order to drink a common Turkish spirit known as rakı.

The song is in Turkish, but the chorus as performed by Marko is actually in four languages:

Έλα δώ (Ela do)

Հոս եգուր (Hos yegur)

Ven Aqui

Içemuz raki!

Translated from Greek, Armenian, Ladino, and Turkish, it says:

Come here!

Come here!

Come here!

Let’s drink raki!

The lyrics represent the demographics of old Istanbul, and the song’s recent history similarly follows the city’s changes. Mirroring the state-led policies of cultural homogenization to active and passive destruction of minority cultural heritage, a 2012 version of the song by Turkish singer Gamze Canyurt had its multilingual chorus altered.

In Canyurt’s version, the Armenian is gone, the Greek is mispronounced, and the Ladino “ven aqui” is turned into the Turkish “ver, saki,” as in, “Pour, cup-bearer!” Whether or not this was done on purpose or by a lack of research, the results are the same: the history of Istanbul is once again subtly rewritten to hide the contributions of its non-Turkish communities.

Similarly in the United States, the Turkish language kef repertoire (performed by non-Turks) continues to disappear as music for public consumption. While there were once many famous Armenian, Greek, and Arabic night clubs on Manhattan’s 8th avenue that catered to diaspora communities and interested locals, the last of those clubs have been closed for over two decades. While certain communities of the early Ottoman diaspora spoke Turkish in addition to or in lieu of their native languages, nationalist taboos and the difficulties of passing on complex cultural configurations have led non-Turkish communities to dismiss or downplay Turkish language music, even if it is part of their musical history. Contemporary artists who built their careers and technical mastery with Turkish language repertoires, such as Richard Hagopian and Mal Barsamian, note the pressure to transition away from these songs or perform them without lyrics due to cultural shifts away from Anatolian music that has been labeled “Turkish.”

Despite this unfortunate pattern, the musical legacy of the Ottoman diaspora in the early 20th century is a timeless reminder of a cosmopolitan past that grows further distant with each passing year. At the very least, with this music we can close our eyes and listen, to imagine an Istanbul that once was, even if the descendants of the city have lost their place to history.