Emerging Scholarship is a series showcasing the research and interests of new voices emerging from academia that focus on the social worlds, histories, and traveling cultures of Central and West Asia.

Blake Atwood is an assistant professor in the Department of Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is also the associate director of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies and the coordinator of the Persian language program. His first book, Reform Cinema in Iran: Film and Political Change in the Islamic Republic, was published by Columbia University Press in 2016 and studies the unlikely partnership between the Iranian film industry and the popular reformist movement in the 1990s and 2000s. He is currently working on a new book about the history of video technology in Iran entitled Underground: The Secret Life of Video Cassettes in Iran.

- Your new project Underground: The Secret Life of Video Cassettes in Iran sounds very exciting. Can you tell us a little bit about it?

In 1983, the newly-established Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (MCIG) suddenly banned the personal use of video technology, including video cassettes and video players. It was an effort on the part of the MCIG to consolidate its power over the film industry and to limit what images and sounds Iranians could consume. Analog video was a new medium at the time, and it was uncontrollable. It marked the first time that ordinary users around the world could create, record, and circulate moving images on their own terms and on a large scale. So in Iran this ban, which lasted until 1994, did not do much to curtail the spread of video. Instead, it took the burgeoning video rental industry that had started to develop in the late 1970s and early 1980s and drove it underground, where a robust network of video distribution developed, as individual video dealers moved quietly through city streets delivering movies for rent.

This curious ban set the stage for an incredible story about how everyday Iranians sought access to, circulated, and consumed everything that was available on video: from movies to music videos to TV shows. In the book manuscript that I am currently working on, I tell this story in all of its trials and tribulations. I try to understand how the circulation and consumption of these material objects created communities and helped people understand what it meant to be a citizen in the new Islamic Republic of Iran. I study not only this ban period but also the full life cycle and even the afterlife of these video cassettes in order to understand how the policies and practices of the 1980s created a way of engaging media that continues into the present.

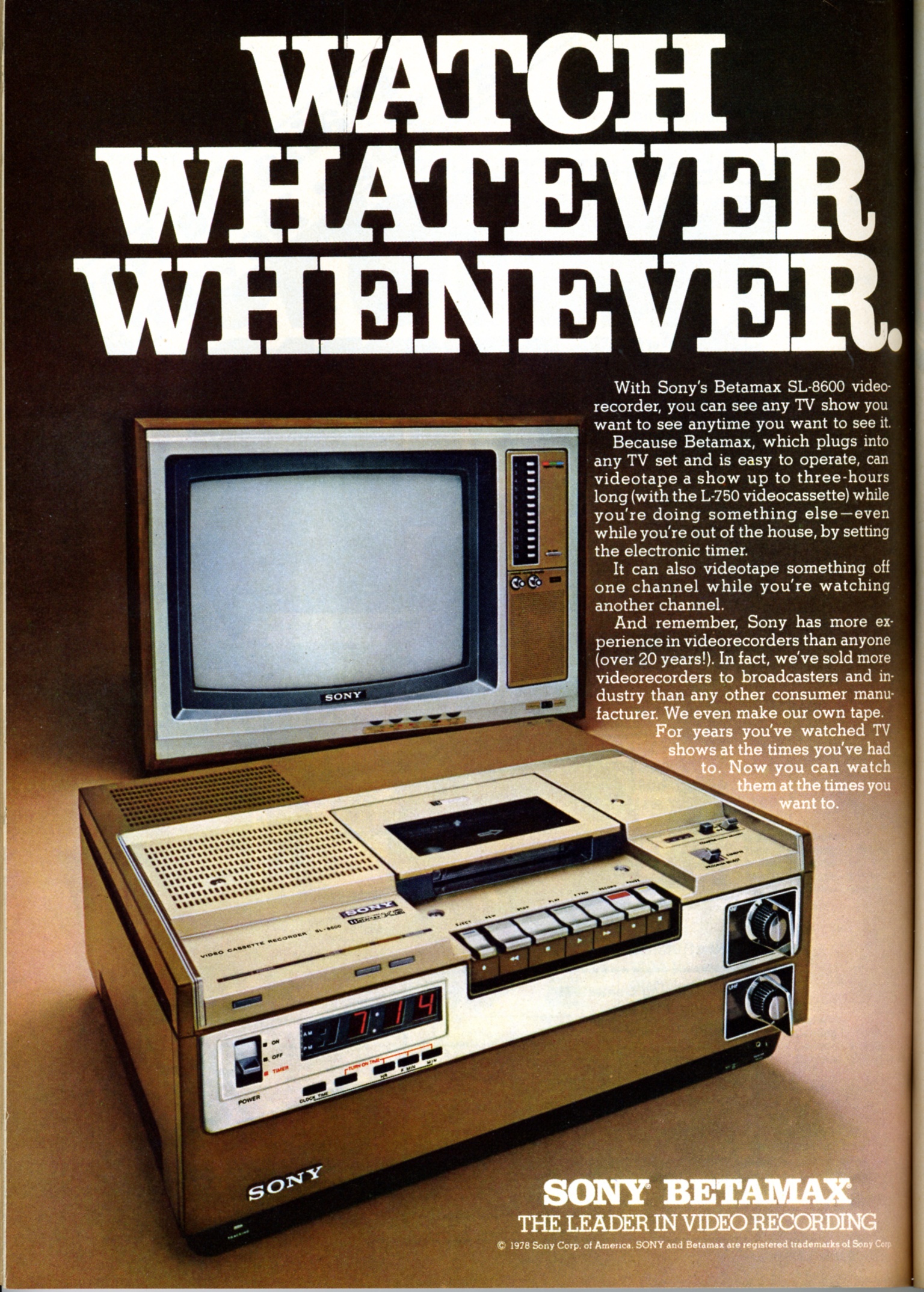

The 1980s were a really fraught moment in Iran’s contemporary history. There was a new government; the country was in the throes of a violent war with Iraq; and then there was this new unruly medium called video. Often times, these various forces seemed opposed to one another. Home video, for example, offered—as the advertisement for the first Sony Betamax player claimed—the chance to “watch whatever, whenever.” This promise was radically different than what the Islamic Republic wanted during wartime, which was to control the media content that people were watching. In this new book project, I show how these oppositions and the ways in which the state and individuals sought to negotiate them clarified a new understanding of public and private space in Iran at this critical moment, both in legal documents and also in everyday practices as people learned to navigate between public and private.

- How did you come to work on this topic?

Like all great ideas for research projects, this one started in multiple places, and then over time it coalesced into a single, coherent book-length project. I’ll tell you two origin stories, one more personal and the other more academic. First, when my PhD advisor retired several years ago, he gave me a huge collection of video cassettes with Iranian movies on them. At that point, I didn’t have a VCR let alone the technology necessary to convert them to a digital format. And that troubled me. I grew up with video cassettes, and they were such an important part of my childhood. So I began to wonder what video cassettes meant to people in Iran in the 1980s and 1990s, and I was also curious to know what happened to their collections, like the one that had just been bequeathed to me.

The most important academic starting point, though, was my first book, Reform Cinema in Iran (Columbia UP, 2016). One of its chapters is dedicated to the rise of digital video technologies, especially camcorders, in the early 2000s and how those new technologies were intersecting with discourses about democracy in Iran. As I tried to contextualize this moment, I discovered that very little has been written about the history of video technology in Iran. So in my first book, I went back to the primary sources and sketched an outline of the history of video technology in Iran, tracing big moments through the state’s policies, including the ban and its lifting. Underground is a much richer engagement with that history and covers not only shifts in policies but also the lived experience of video cassettes and their users in Iran.

Last year I also published an article on home video in Lebanon during the Civil War (1975-1990), so my interest in analog video technologies and their particular histories in the Middle East is longstanding. I have been working on this current project about Iran for almost three years now.

- You use the term “underground distribution network” to describe the video “dealers” and their relationships to each other and to the spaces that they occupied in society. What do these terms do for you?

I developed the term “underground distribution network” in order to describe the way in which I saw video cassettes circulating in the 1980s and 1990s in Iran. Recent scholarship in media studies has cultivated the term “informal media industries” to describe this kind of circulation. Certainly what happened with video cassettes in Iran was informal, because it was outside of formal industrial and state control. But because so much of what is happening with video cassettes in Iran has to do with space—and specifically public and private spaces—I wanted to recuperate the notion of “underground” as an alternative way of thinking about how video cassettes moved through all kinds of spaces in Iran. We typically think of the “underground” as a dirty space, one ridden with crime and theft. But in my work, I view the underground more as a third space in which public and private interests confront one another, sometimes violently or forcefully but more often casually or ambivalently. It is through these encounters in the underground—where questions of legality and illegality are murkier—that people came to understand the divisions between public and private that often structure mainstream society.

The idea of a network proved productive as a way of adding a sense of coherence to what would otherwise seem like a chaotic system. It also gestures towards some of the qualities that make analog video technology so exciting in the first place. In my research, I keep confronting myths about the navār-e mādari or the mother cassette, from which hundreds or even thousands of other cassettes of a particular movie would be produced. Such a myth acknowledges the reality that this was bootlegging economy, in which people copied cassettes in an unregulated and sometimes arbitrary way and then benefitted financially from their circulation. This idea of a mother cassette, though, also insists on the same idea of interconnectedness that is captured by the term “network.” Even though so much of the circulation of video cassettes came down to individuals, the whole system created a sense that people were connected in a material way, not just through what they watched but also how they watched it.

Central to the idea that people were connected through video cassettes is the labor involved in transporting them, and this is where the idea of the “dealer” comes into play. Of course, this term “dealer” is my own creation. In my research, I’ve seen and heard references to the individual who delivered videos for rent to people’s homes as a filmi (film guy) or vide’u man (video man) or even vide’u kolub-e sayyār (mobile video club). But in all of my research I have never seen references to a Persian word that might be equivalent to “dealer” like forushandeh (seller). Rather in my own analysis I chose the word dealer in English strategically, because I wanted to speak more directly to the existing scholarship on video industry labor in Africa, North America, and Europe, and I also wanted to position the movement of video cassettes alongside other contraband items that came into and moved throughout Iran, where we often encounter the word dealer, e.g. drug dealer or arms dealer.

- What were people watching? Was it mostly pre-1979 Iranian films? Or were foreign films being exchanged as well?

The diversity of what people were watching has surprised me more than anything. The short answer is that people watched whatever they could get their hands on, and that included Hollywood action movies, popular Iranian films from before the revolution, European art-house films, and Indian musicals that people would watch even if they didn’t have subtitles or weren’t dubbed. But it wasn’t just movies that people were watching. Music videos were also a big deal. Interestingly, music videos were often included after a movie, filling up the remaining space in a video cassette so that people felt like they were getting their money’s worth from a rental. Later, especially after the large-scale arrival of satellite dishes in 1991, people watched TV shows on video from places like Turkey and the United States. During my research, I actually got the chance to check people’s video collections, in addition to hearing about their memories and recollections about what they watched. So I do have concrete information about what people have chosen to keep.

Part of my interest in studying the video dealers who supplied stocks of video cassettes to Iranians is understanding their role in mediating taste in Iran at this time. I am working right now to explore how they understood this responsibility and how, in turn, their customers viewed the work they did. I also have a chapter that examines how a generation of Iranians who grew up with these underground video cassettes developed a world view and a particular way of consuming media that continues into the present. Here I study concepts cinephilia and look at the impact of video cassettes on film pedagogy.

- How are you researching all of this?

A project like this demands a diverse set of research tools. I have done archival research and scoured newspapers and trade publications in order to establish the public discourse about video at this time. I have also spent a lot of time closely reading laws and policies regulating video distribution and production at various times in Iran. These sources have given me a good understanding of the state’s narrative of video, but since the state is only one small part of my project, I’ve had to seek out other research methods as well. In order to study this illegal history, I have turned to oral history. So far I have done around 50 interviews, about a third of which involve people who were directly involved in circulating movies on video cassettes, primarily dealers. It is their memories and stories that, I hope, will make this a really dynamic and colorful book.

I should mention that oral history is not a common research strategy in media studies. Recently scholars like Miranda J. Banks have started using it in their articles on formal media industries, but I have never seen a media history book built around a corpus of oral history interviews, so I view this as one of my important contributions with this project. I hope it will inspire more critical engagement with oral history within the historical study of media. Those of us who work on the history of media outside of North America and Europe often don’t have access to tidy archives or collected papers to facilitate our work, so alternative ways of gathering data like oral history are crucial to preserving histories like video cassettes, which are at risk of disappearing.

- Have you come across any dealers in your oral history interviews? How do they remember this particular period?

I’ve been very lucky to interview quite a few dealers. I say lucky because I know that speaking to me was difficult for them, both emotionally but also pragmatically since the work they did was in no uncertain terms illegal. These men (so far I haven’t heard of any women dealers) put themselves in incredible danger in order to do this job and to bring happiness and entertainment to people’s lives during a particularly difficult period in Iran. I have been struck by how varied their experiences and motivations were. Some of them were in it mainly for the money—reports show that this was a multi-million-dollar industry by the end of the ban—while others were really committed to fostering a diverse movie culture in the country. Preliminarily, I have noticed a shift over time from the former model to the latter one, with the earliest generation of dealers more interested in financial gain and the later generations committed to the ideals of movie access.

I heard one particularly compelling story from a dealer, and it has always stuck with me. Hamid was part of the early generation of underground video dealers, and he had built a modest but successful business for himself by renting video cassettes to a few families in Tehran. In the late 1980s, however, he decided to leave Iran and emigrate to the United States. In order to process his visa, he had to travel to the U.S. Embassy in Turkey. During his interview with the consular staff, they asked him about his profession. Hamid found himself caught in a catch-22. Should he lie or confess that he worked in an illegal trade? In the end he chose honesty, and he struggled to say that he dealt in the illegal distribution of video cassettes. When he did finally get it all out, his interviewers started to laugh. The confused look on his face caused one of them finally to say that it was a “silly profession.” He would later tell me that he has always been unsettled by that laughter and how it refused to acknowledge the real risks that he took and the escape that he provided his handful of customers, who eagerly awaited his arrival once a week so that they could watch movies and cope with violence and instability around them. For these Americans at the embassy, video technology meant something entirely different than it did for Hamid and other Iranians like him.

The reason that this story always stands out in my mind is because it shows how we need an account of the history of video technology in Iran. We cannot assume that video landed in the same way everywhere that it traveled; every place has its own unique encounters with new media technologies. Those histories need to be studied and recorded. We often think that we now live in a time of tremendous technological change (and that might be true to a certain extent), but if we want to understand how the Iranian state understands and regulates digital media, we need to go back to these earlier analog technologies that necessitated media regulation for the first time in the Islamic Republic.

- Memory seems to be a huge part of your work. How much of this has been preserved on an individual level?

One of the reasons that I find oral history so productive to the work that I am doing is precisely this question of memory. To engage in oral history as a methodology is not to cull interviews for information but rather to reflect on how people have remembered certain moments in their lives. It also aims to contextualize people’s memories and experiences rather than extrapolate or generalize based on them. In this sense, it is an acknowledgement that everyday people’s lives, experiences, and memories have something to contribute to the study of history. As you said, the rich details of this period are actually preserved on an individual level. The illegality of video meant that there wasn’t space in the public sphere for the work of collective remembering.

Throughout my research, I have tried to remain sensitive to or in touch with questions about memory formation and the different acts that actually constitute remembering. The last chapter of the book deals forcefully with the question of memory by studying a variety of ways in which Iranians have, over the last twenty years, sought to remember the age of video cassettes now that it has become a fallen media technology: everything from collecting and magazine articles to academic publications, novels, and popular movies and documentaries. In this chapter, with the help of colleagues, I have been working to deploy a definition of nostalgia that is dynamic and multi-faceted rather than just viewing it as a flat, emotionally-saturated longing for the past.

- How has working on this project been different than writing your first book?

When I think back to researching and writing my first book, it was really a solitary act. I spent a lot of time alone watching movies and reading microfilm in libraries. But this current project has forced me out into the field, where I am talking to people and listening to what they have to say. This is really transforming the kind of story I will be able to tell in this book, especially as I try to showcase the social life of video cassettes. I am trying to capitalize on that momentum by also sharing my writing with more people this time around to get feedback as I revise. Already I feel so grateful to the many people who have given generously of their time both in interviews and in commenting on my work; other people’s enthusiasm for this project has helped me stay focused and motivated.

At the same time, this book is my attempt to redirect the conversation about the history of motion pictures in Iran to attend more forcefully to questions of distribution, exhibition, reception, and materiality. I am not alone in this call, and there are a handful of other talented scholars doing similar work in this regard, including a brilliant cohort of PhD students at the University of Texas at Austin.

Because this book is so important to me and because it has grown out of social way of researching, I am really committed to making it accessible to a more general readership, especially to students. For that reason, I am so excited to have had this chance to debut my new project on Ajam Media Collective. What I admire most about the work you all do is its accessibility: taking complicated ideas and turning them into an experience that is rigorous but also appealing to readers today. It is a real model for all of us in the field.

One final note: if any of you reading have powerful memories of video cassettes in Iran or were involved distributing them, I’d love to hear your stories. Feel free to contact me at blake.atwood@gmail.com. Thank you!

Cover image, Visualizing the “Underground Distribution Network,” provided by Blake Atwood.

1 comment