All photos taken by author Alex Shams, unless noted.

Along either side of the Euphrates river as it passes through southern Iraq, a narrow band of fertile soil blossoms with verdant overgrowth, date palms, and paddies full of aromatic Anbar rice. Just north of Najaf, home to the gold-domed tomb of Imam Ali, sits the village of al-Kifl in the heart of Iraq’s rice belt. Pronounced by locals as “a-Chefel” – the “k” slipping into a “ch” in the way common to the local Arabic dialect – al-Kifl is home to a small, winding mud-brick bazaar and houses that sprawl into farmland for miles around.

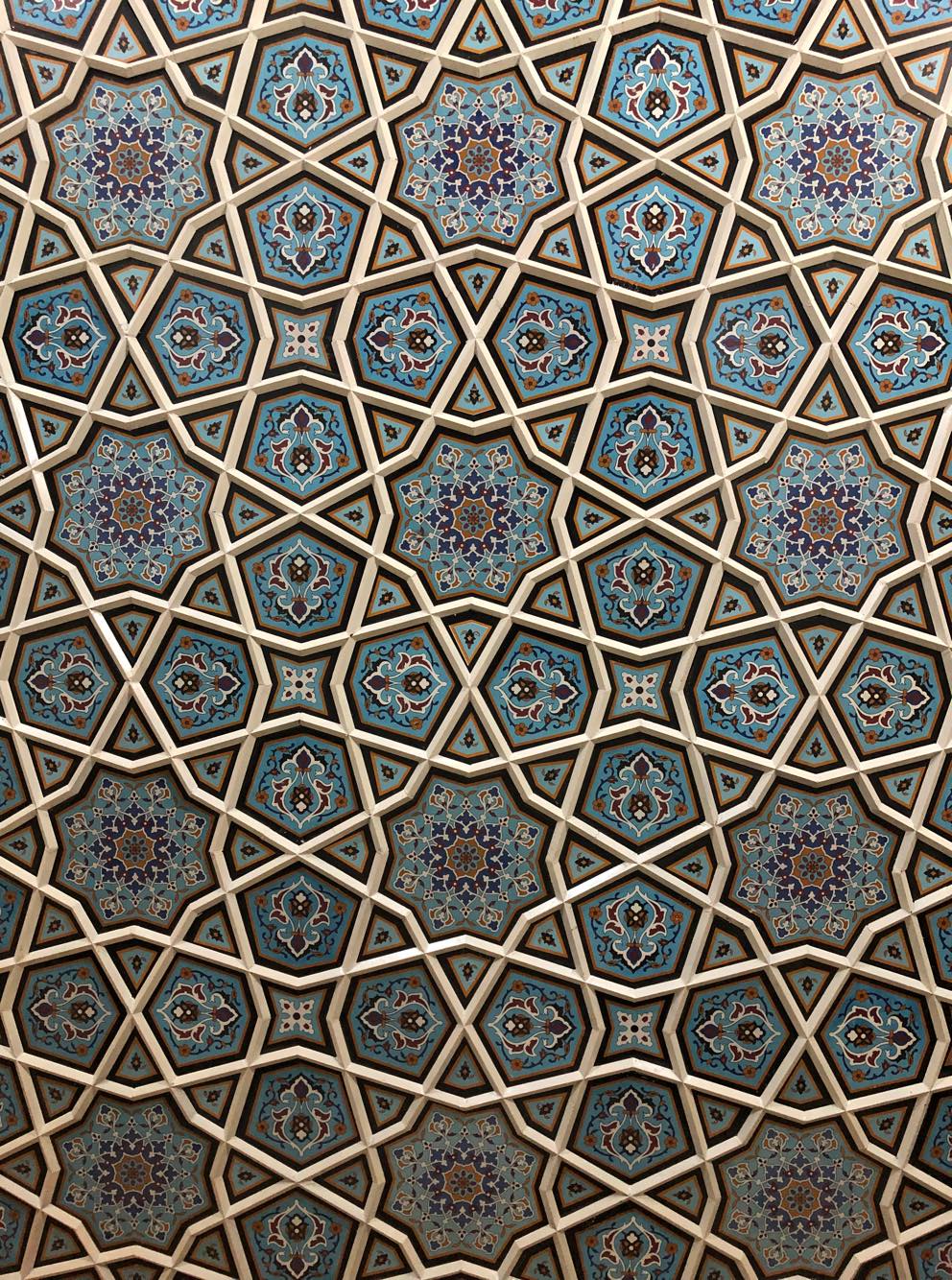

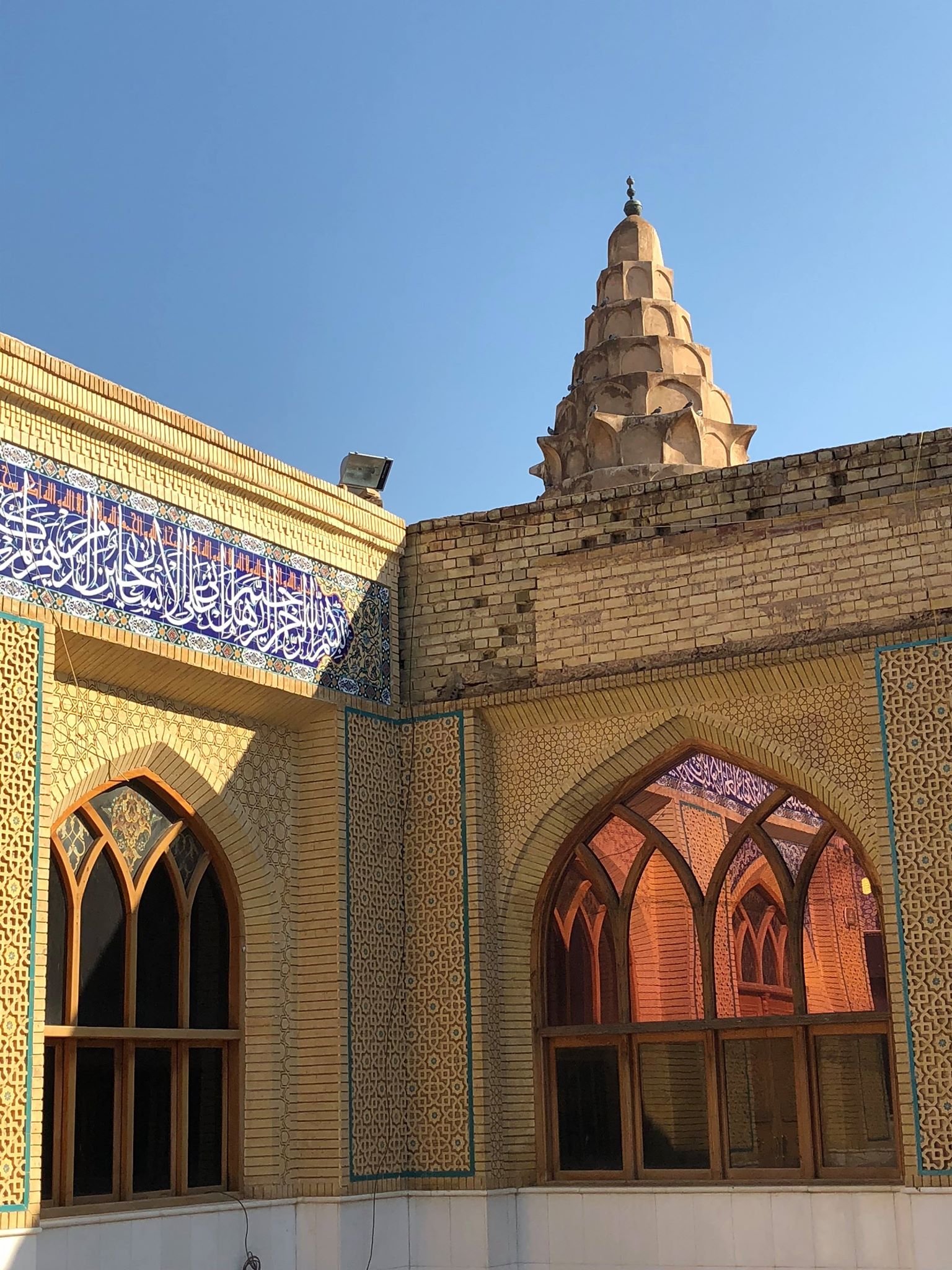

Al-Kifl is an ordinary Iraqi town, except for one thing: the synagogue that gives the place its identity. Down the narrow lane of al-Kifl’s bazaar, through a small passageway whose overhang is covered in geometric turquoise tile work, sits the shrine of the Biblical Prophet Ezekiel.

Known in the Islamic tradition as Dhu’l-Kifl (ذُو ٱلْكِفْل) – from where al-Kifl derives its name – or in the Arabic Christian tradition and Persian as “Hazaqiyal” (حزقیال or حزقیل نبی) and Hebrew as Yechezqel (יְחֶזְקֵאל), the prophet’s tomb is located in an ancient Jewish shrine enclosed in an Islamic mosque. Ezekiel’s Tomb is a testament to millenia of religious diversity in Iraq, and for centuries has been a place of shared Jewish and Muslim pilgrimage.

Ezekiel’s Tomb is one of those rare, beautiful places where Arabic and Hebrew flow freely into each other, a reminder of the long history of Iraqi Jewish history on this soil.

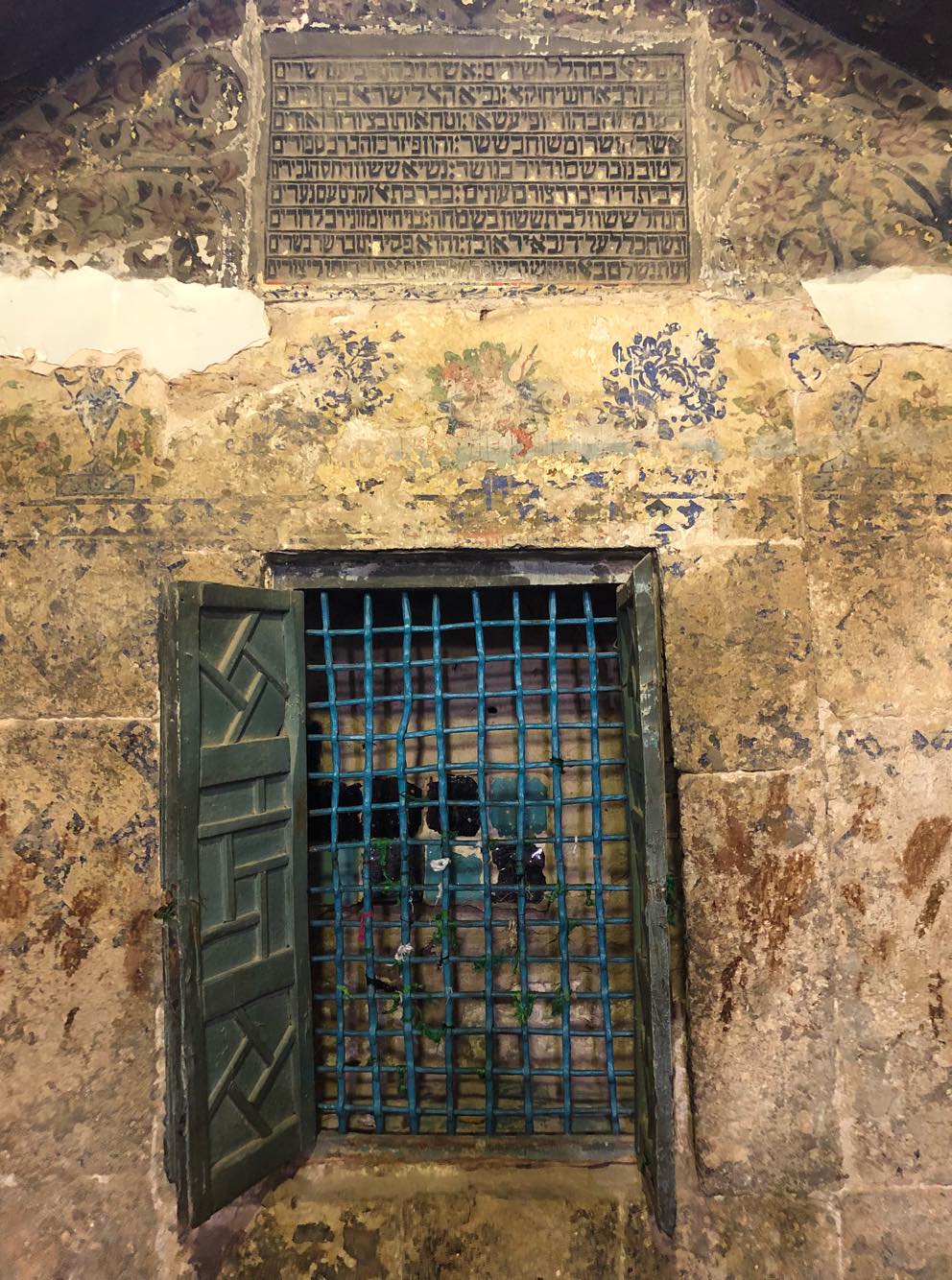

Inside the inner sanctum, Hebrew is engraved on wooden plaques and painted onto inscriptions on every side of the tomb.

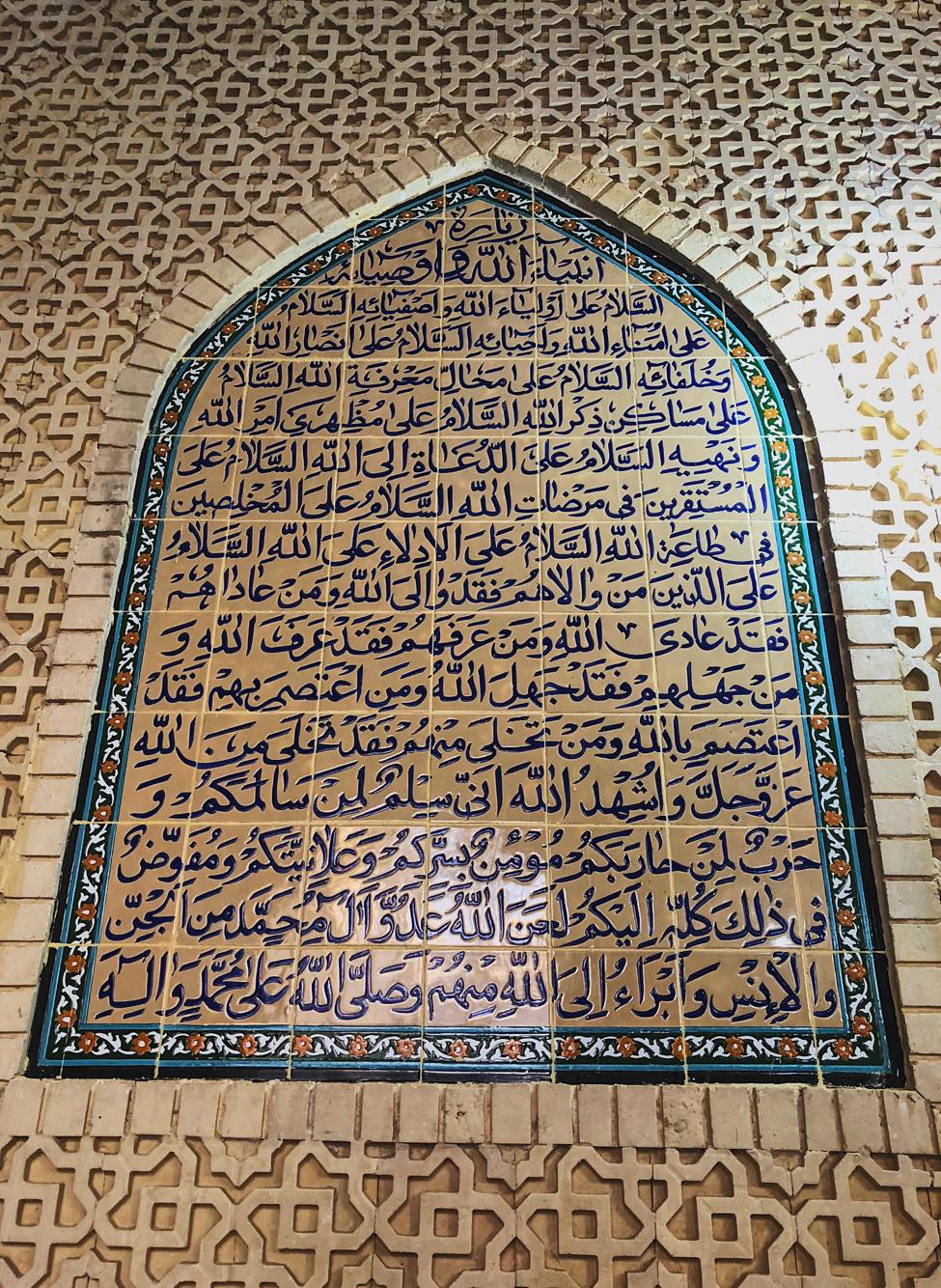

The coffin itself is covered in Arabic calligraphy wishing peace upon the Prophet. Ezekiel is mentioned in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim scriptures alike, a reminder of the three faiths’ shared Abrahamic roots.

The tomb is thought to date back to the 500s, when Jews lived in a land that was a mix of Christian, Zoroastrian, Manichean, Mandean, and polytheistic communities. When Islam entered Iraq, Ezekiel’s Tomb, like other shrines, added Muslim visitors to the mix.

This was a pattern across the Middle East, where Muslims – both from the Islamic armies and locals who converted later – continued to revere local holy places, especially the graves of figures from the Abrahamic tradition. The same phenomenon can be seen at holy sites in neighboring Iran, too, like Daniel’s Tomb in Shush or the Tomb of Esther and Mordechai in Hamedan.

Historian Zvi Yehuda notes that famed Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela visited in 1170, and at that time Jews would make pilgrimage in the fall between the Jewish New Year (Rosh Hashanah) and the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur). Not only did Jews and Muslims worship alongside each other for centuries at this site; their practices influenced each other. Zvi Yehuda argues in The New Babylonian Diaspora that the Jewish tradition of visiting Ezekiel’s shrine and prostrating before the tomb emerged after the arrival of Islam.

These rituals are similar to the Shia ziyara traditions at the nearby tombs of Imam Ali and Imam Hussein. Ezekiel’s Tomb is located on the main road linking Najaf and Karbala, Shia Islam’s holiest sites, as well as on the road that leads Hajj pilgrims to Mecca, situating it at the heart of regional Muslim pilgrimage routes.

In the 1300s, under the Mongol Ilkhans, a mosque was built around the site, in keeping with a widespread policy of shrine patronage around the empire. The ancient minaret at Ezekiel’s Tomb, which today leans sharply, is thought to be from that era. Its construction began under the Ilkhanid king Oljeitu, who converted to Shia Islam and was known in Persian as Muhammad Khodabandeh.

With the extension of the mosque around the front, Jewish access became controlled by mosque authorities, who collected dues from pilgrims. The economy of Al-Kifl, which had become mostly Muslim, thus became directly dependent on the Jewish pilgrimage.

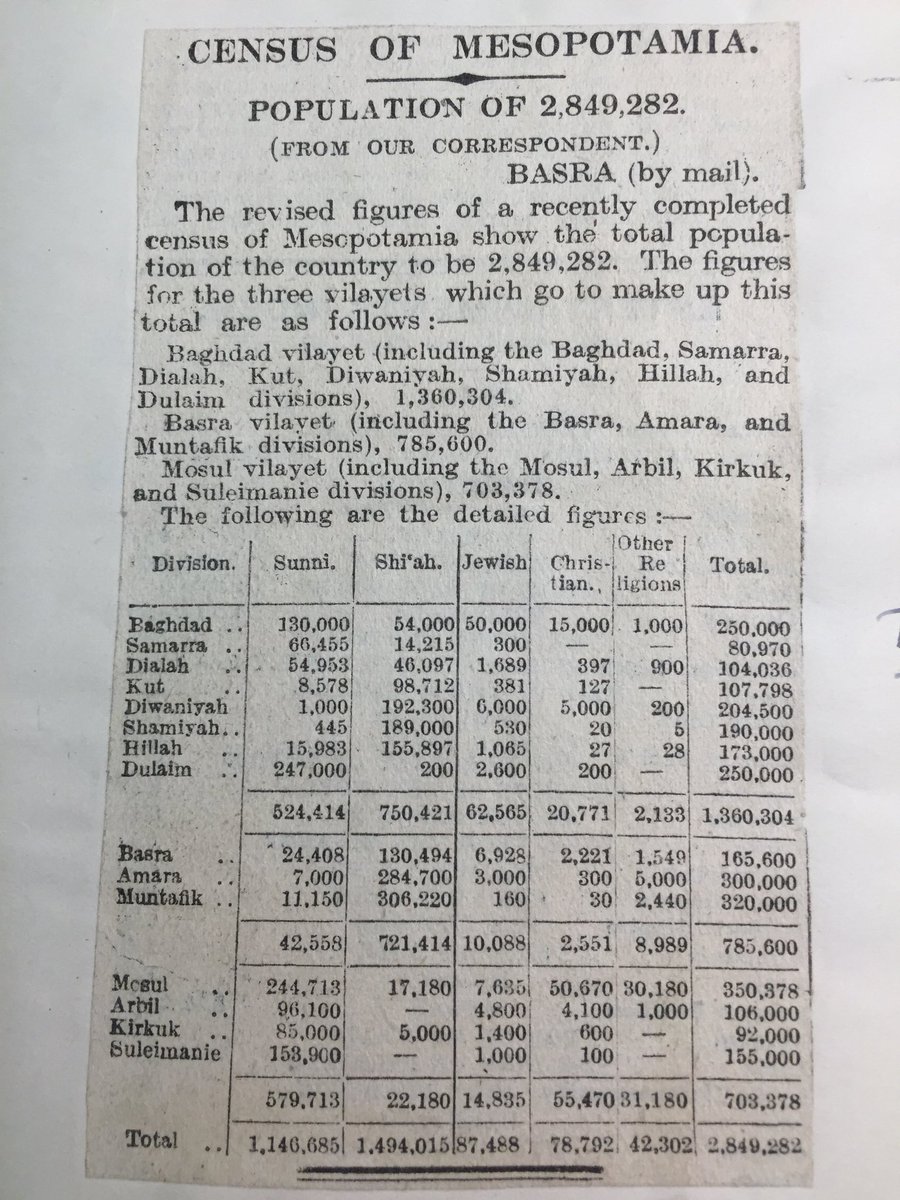

Ezekiel’s Tomb is not just a reminder of ancient history; it is a testament to religious diversity that existed well into the 20th century. Jewish communities existed among Christians, Muslims, Yazidis, Mandeans, Hindus, and others across Iraq. In the early 20th century, one-third of Baghdad was Jewish.

In an interview with Ajam, historian Annie Greene said that records indicate that in the 1800s and 1900s, Iraqi Jews made the pilgrimage – known by the Arabic term ziyara – yearly to Ezekiel’s Tomb at the Shavuot holiday, which follows Passover (Pesach, Eid al-Fusḥ) in late Spring. Jewish pilgrims came from Baghdad and Hilla, both home to large Jewish communities.

The pilgrimage to Ezekiel’s Tomb was the most important in the ritual calendar of Iraqi Jews, and Greene notes that it figures prominently in their diaries, autobiographies, and memories, regardless of gender.

After part of the mosque collapsed in a flood in the 1700s, Ottoman authorities gave Jews permission to carry out major repairs. Yehuda argues that Jewish community leaders used the opportunity to convert much of the mosque back into a synagogue, removing Islamic symbols and constructing a yeshiva, a Jewish religious school.

Muslim tribes around the town, meanwhile, were given the role of protecting the shrine. Beginning in the 1850s, Jews from across Iraq began building homes and religious institutions to host pilgrims at al-Kifl.

Al-Kifl’s role in the Jewish community mirrored the role of the nearby holy cities of Karbala and Najaf for Shia Muslims, becoming hubs of communal religious life which came alive during pilgrimage season with the arrival of pilgrims from across the region.

Greene argues that the mid-19th century rise in Jewish claims on shrines, like at al-Kifl, was a result of their empowerment amidst wide-ranging legal reforms promising equality for Ottoman citizens, irrespective of religion. Of the four Iraqi representatives in the first Ottoman Parliament in the 1880s, one – Menahem Salih Efendi Daniel – was Jewish. In total, 4 or 5 Jews were members of the Ottoman Parliament.

“There was this sense,” Greene explained during an interview,” that if you invested in the government, perhaps it would invest more in you. Economic and political elites from the Jewish community took up that investment.” The gradual empowerment of local Jewish communities continued apace as Iraq gained independence in the early 20th century.

All this changed with the emergence of the state of Israel. Beginning in the 1900s, Zionist groups began acquiring land in British Mandate Palestine with the aim of creating a Jewish state. As it became clear that this Jewish state would have no place for indigenous Arab communities, local Palestinians rose up repeatedly in revolt. British atrocities and Zionist reprisals against Palestinians incensed public opinion across the Arab World, leading to riots that often took aim at local Jewish communities unrelated to events in Palestine.

Britain took control over Iraq as a colonial power after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, and riots over the Palestine issue in Iraq often took an anti-British colonial tone as well. When chaos broke out after a pro-German general took power in a coup in 1941, for example, rioters in Baghdad targeted both Iraqi Jews and British citizens, sacking the Jewish Quarter in a event called the “Farhud” that left dozens dead while also attacking shops owned by local Indians, who were British subjects.

Things stabilized in the days and years that followed, and Iraq’s government gradually became independent of British colonial power. In 1948, when Zionist militias carried out the Nakba – the forced exile of 750,000 Palestinians from their homeland, in which thousands died – the Iraqi government began to take reprisal measures against local Jews, using the existence of a minority that had joined the Zionist movement as an excuse to punish the whole community. In fact, it was Communism that attracted the support of most Iraqi Jewish intellectuals, as well as Shia Muslim intellectuals.

In this climate of fear and persecution, tens of thousands of Iraqi Jews left for Israel. A few thousand remained, but continued persecution over the years that followed spelled the end of the community. The last time Ezekiel’s Tomb saw masses of Jewish pilgrims was in the 1950s.

After the Jewish exodus, Muslim caretakers took over the site. While Muslim pilgrims continued to visit, the end of Jewish pilgrimage sent the local economy into decline.

In the early 2010s, an Iranian company was charged with restoring the mosque.

In the early 2010s, an Iranian company was charged with restoring the mosque.

Some initially feared that the restoration would compromise the site’s Jewish history, but in the end a compromise was reached: the outer courtyard would be restored as a mosque – which is how it was being used – while the inner sanctum, under the authority of Iraq’s heritage authorities, would be left with its Hebrew markings remaining as they have for decades since the Jews left. The Iranian company charged with preservation efforts appears to have carried out renovations on the tilework and other aesthetic features inside the sanctum, but otherwise left it as it was.

Debates over the tomb’s present and future highlight the complexities of historical preservation at sites holy to multiple communities. Preservation requires balancing respect for those to whom the site previously belonged with the interests of a community that actively uses it today.

In the restoration of al-Kifl, however, the renovation of the shrine’s “mosque” included de-emphasizing Jewish features or erasing Hebrew inscriptions that result in more emphasized Muslim character. This was intended to make the site work for Muslims who currently worship at the site, while simultaneously preserving Jewish historical features inside the sanctum.

Shrines are “living buildings,” as art historian Stephennie Mulder argues in her book, attracting the patronage of leaders and states seeking to express “everything from the most high-minded piety to the basest of politics.”

Just as in the mid-1800s, when Iraqi Jewish leaders allied with the Ottoman sultan to convert al-Kifl’s mosque into a Jewish religious center, today the synagogue is increasingly coming to resemble a Shia Muslim imamzadeh shrine.

Iraq has in recent years become an international center of Shia pilgrimage, with nearby Karbala and Najaf hosting 25 million pilgrims during the religious observance of Arbaeen. In the rituals associated with Arbaeen, pilgrims travel the road between Karbala and Najaf on foot, passing near al-Kifl.

Some of these pilgrims visit Ezekiel’s Tomb, slowly turning the site into a site of transnational Muslim pilgrimage. While their increasing numbers revitalizes the local economy, the shrine’s Jewish history becomes less and less pronounced, with tour guides stressing the site’s Islamic past.

But the Hebrew inscriptions of the inner sanctum tell a different story, a reminder of centuries of Jewish presence and shared life with Muslim neighbors across Iraq.

Iraq’s Jews are today long gone, but the shrine’s heart remains untouched, protected by Muslim caretakers until it’s former devotees can one day return.

Next Shavuot in al-Kifl, inshallah.

References

Bashkin, Orit. New Babylonians: a History of Jews in Modern Iraq. Stanford University Press, 2012.

Campos, Michelle. “From ‘Ottoman Nation’ to ‘Hyphenated Ottoman’: Reflections on Multicultural Imperial Citizenship at the End of Empire,” Ab Imperio 1 (2017), 163-181.

Greene, Annie. “Burying a Rabbi in Baghdad: The Limits of Ottomanism for Ottoman-Iraqi Jews in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Jewish Identities (forthcoming) vol. 12, 2, (2019).

Mulder, Stephennie. The Shrines of the ‘Alids in Medieval Syria: Sunnis, Shi’is and the Architecture of Coexistence. Edinburgh University Press, 2014.

Yehuda, Zvi. The New Babylonian Diaspora: the Rise and Fall of the Jewish Community in Iraq, 16th-20th Centuries C.E. Boston: Brill, 2017.

10 comments

My father was born in Hillah in 1934 and was circumcised near Ezekiel’s tomb. He was named Yechezqel (יְחֶזְקֵאל).

Thank you so much for this amazing factual article.

Since childhood I wish to be able to go visit this place.

Maybe one day….

Wow! So cool Daphna, I love the prophet Ezekial. His faith, the visions, and he never lost site of H-shem! Loved this article too! שבת שלום יפה פרח ️️

Informative

While it is gratifying to know that some of the original Jewish decoration and Hebrew inscriptions remain around the burial chamber, the tomb has been increasingly islamised. Muslim Pilgrims are not told about Ezekiel – this is the burial site of Dhu al-Kifl, a minor prophet in the Koran. There was never an Arabic inscription on the tomb cover until recently. This is not a tomb where Jews and Muslims worship side by side, the Jews have been banished and the Muslims have apppropriated it as theirs. The huge Shia shrine has been built since 2010 and dwarfs the original shrine. ‘Next Shavuot in Kifl?’ not likely while most Iraqi Jews, now Israelis are not allowed in the country. We do not know what became of the graves of the Geonim, the Jewish dignitaries, including Menahem Daniel. Have these been destroyed? Although we appreciate the photos, the revisionist history of Palestine does nobody any favours.

It is Heskell Sassoon, the family name is Sassoon not Heskell.

Different family.

Sassoon Eskell was his name, his family name was Shlomo-David. This is a common mistake.

My family are Sassoons. My great-great grandfather was Solomon David Sassoon.

All of the Sassoon family fled Iraq in the 1930s-40s due to pogroms and violence.