The following is a guest post by Samaneh Moafi, a researcher and practitioner in the field of architecture based at Forensic Architecture, Goldsmiths University of London. She holds her PhD from the Architectural Association (AA) with a thesis on the intersection of class and gender in state initiated mass housing developments in Iran.

This article has been commissioned for the inaugural Sharjah Architecture Triennial, titled Rights of Future Generations. It is published as part of Conditions, an editorial collaboration between the Sharjah Architecture Triennial and Africa Is a Country, Ajam Media Collective, ArtReview, e-flux architecture, Jadaliyya, and Mada Masr. Conditions is a series of essays that are published first online and later as a book, available from November 2019.

Mehr from Samaneh Moafi on Vimeo.

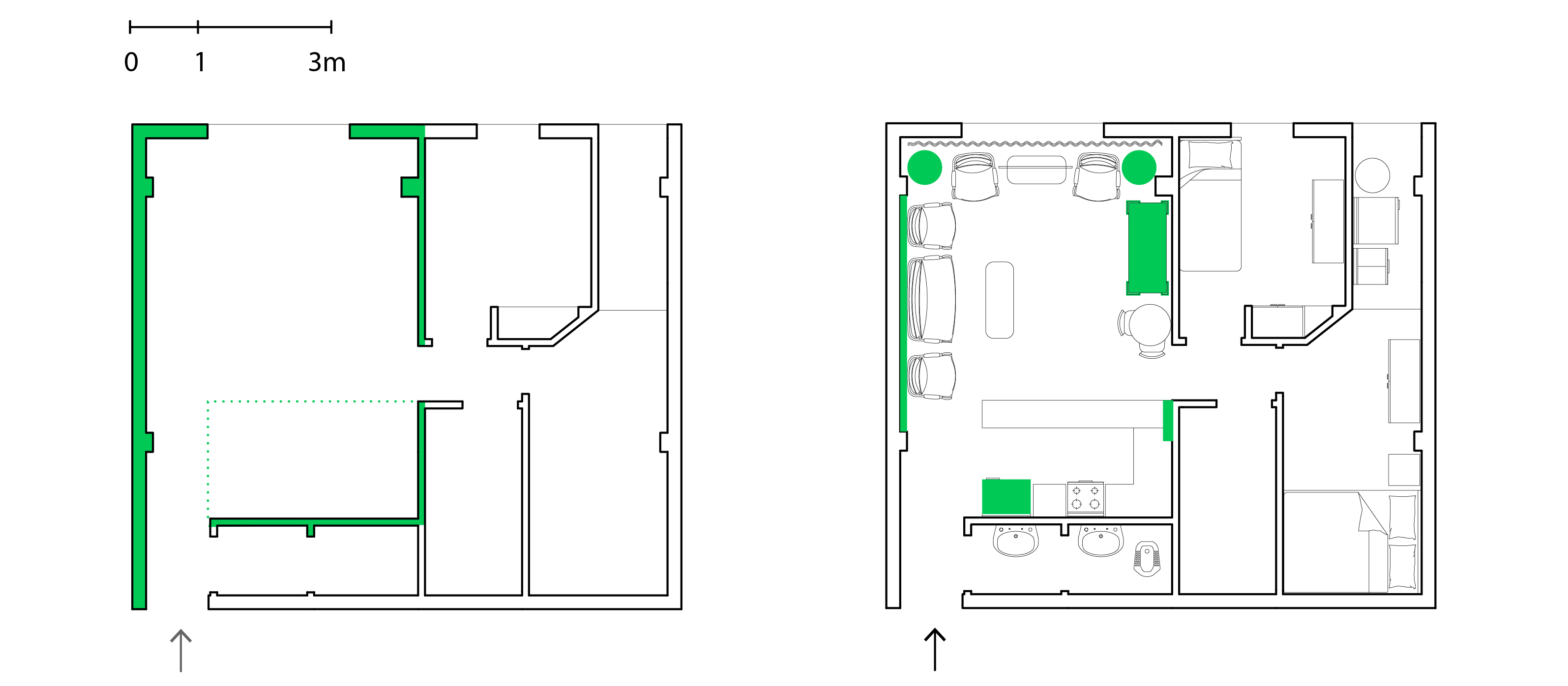

The first feature that grabbed our attention was a small wall, 20 centimetres thick and 1.5 meters long. Mahsan spent much of our time lingering around it, examining it closely. At its front was a 16 square meter space with a window wide enough to bring in natural light. Behind it was a smaller space with a short depth of 1.5 meters; the floor level was raised, suggesting a different intended use from the rest of the apartment. This was also evident in the materiality of the surfaces, mud-coloured ceramic tiles in contrast with the plaster finish elsewhere.

This was the summer of 2016, and we were standing in a brand new apartment in Esfahan named Mehr, meaning compassion in Persian. Conceived in 2007 by Iran’s then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the Mehr housing scheme entailed the construction of 4 million working-class dwelling units in the peripheries of large cities across the country. An estimated 12 million people, equivalent to Tehran’s population, were to be settled in these homes. Mehr was to become one of the largest state welfare schemes in the history of the Islamic Republic.

Not every working-class Iranian could apply for a Mehr home. To prove her eligibility, Mahsan had to prove she was moto’ahhel (متاهل – married). She had to present her husband as the head of a nuclear family and show that he had never owned property. In other words, she had to prove she had married a man incapable of securing a roof for his wife. It had been some time since Mahsan had decided to move out of her parental home and live independent of her father. Mehr seemed like a perfect solution, as her fiancé was from a working-class background with no savings and was making ends meet with day jobs. Shortly after learning about the scheme, therefore, Mahsan married her fiancé and applied for a Mehr home.

The wall that Mahsan was examining in her apartment didn’t fully divide the yet-to-be living room from the yet-to-be kitchen—it was less than half the width of the space. The wall’s limited size signified the austere context in which it was located. In mass housing schemes, the floor space occupied by walls is considered a waste. Minimising wall space can help reduce both the cost of construction and the minimum area required by a dwelling unit. In other words, the thinner the walls and the shorter their length, the greater the number of units that can be fit into a building. This rule of thumb can allow more people to be housed in a set area. No partition between the kitchen and the living room is ideal for this economy of space. In fact, many of the Mehr homes built elsewhere in earlier phases had open plan layouts. The apartment we were visiting, however, was built later on and included a wall that resisted the economic austerity of its context.

Iranian homes were traditionally organised around a separation between andaruni space, interior and linked to women and children, and biruni, exterior and linked to male guests. Yet, the reason for the partition in Mehr homes had little to do with tradition. Halfway through the project, a political attack was organised against the open layout of the apartments, led by popular religious figures. Ayatollah Javadi Amoli, for example, put forward an argument according to which an open plan house was unfit for orchestrating the everyday life of an Islamic nuclear family where the dwelling of women should be protected from the gaze of visiting na-mahrams (unrelated male guests), and a partition is necessary to close off the space assigned to them—the kitchen. This partition, in Javadi Amoli’s argument, was the essence of Islamic architecture and a signifier of resistance to western paradigms of living. Condensed in the thickness of the un-assuming partition wall of the Mehr house we were visiting, therefore, was both a resistance to the West as well as a familial form of patriarchy: in effect, separating the genders according to the works of cooking and being cooked for, secured a hierarchy between them.

Having examined the wall, Mahsan muttered that the living room was too small for the kinds of things she had always wanted to do. She took her eyes off the wall, turned to her husband, Mehdi, and her father-in-law, Haji, and said with a firm voice: “As the young bride of the family, I want to have all of my in-laws here together, you know…”. She then turned to me and continued: “I think the best way to deal with this situation is to knock down this wall. The neighbour next door has done the same. It’s the only way…”. I was intrigued. The wall was small, and its role in fully separating women from the rest of the household, as Ayatollah Javadi Amoli had mandated, was more ideological than practical. More than marking the collapse of resistance to the West, Mahsan’s argument registered her struggle in defining her new role as a wife and a homeowner.

A wall, demolished

One of Mahsan’s neighbours, Leila, invited us over to show how she had removed her partition wall. Following the removal, she arranged her furniture, more specifically her jahaaz, in a way at odds with the intended use of the space. In its origin, “jahaaz” refers to a collection of elements that orchestrate a performance. For example, “breathing jahaaz” (جهاز تنفس) refers to those internal organs that regulate the practice of respiration: the nose, the mouth (oral cavity), the pharynx (throat), the larynx (voice box), the trachea (windpipe), the bronchi, and the lungs. In colloquial Farsi, jahaaz refers to a dowry, a set of domestic devices prepared, arranged, and given as a gift to the bride as she moves from her parental home to her marital one.

The jahaaz is expected to include a variety of furnishings, ranging from sugar cubes to pickles, china plates, duvets, carpets and electric appliances. Together, these enable the bride to appropriate an unfamiliar house and enact her desired habits and rituals. Leila had positioned the most aesthetically pleasing decorative elements of her jahaaz around the perimeter of the new open space made up of the kitchen and living room, deploying them on everything with a top surface area including shelves, vitrines, table tops, cabinet tops and even the fridge. It seemed as through these objects had enabled her to remove the possibility for the space to be used for cooking and washing—more generally, reproductive labour.

Over the following years, this localised but incisive intervention gave rise to effects that unexpectedly echoed in other parts of Leila’s daily life – and spiralled out of control. The new open plan layout set in motion a new life that relied on convenience foods and limited time spent toiling over hot stoves. Leila could no longer prepare the most basic dishes of Iranian cuisine, such as ghormeh-sabzi , as they took hours to cook and the herb odours would quickly take over the house. The odour was only the tip of the iceberg: If she was to have guests, be it a friend, a new acquaintance or her in-laws, they would see her labouring over the pots and dishes. This shattered her desired image of an unstressed host who would have everything under control. Since there was no partition, all of the labour that would have otherwise been hidden from guests was exposed, creating an uneasy situation for both sides.

To tackle this problem, Leila tried relying on takeaway food. Smartphone applications for food delivery, such as Snappfood, were not useful since their search engine only worked within a couple of kilometres, and the Mehr houses were too far from their nearest cities. Leila had to make an arrangement with a restaurant and ask them to send the food by taxi. She would ask them to not bring the food upstairs and leave it in the carpark. Once it arrived, she would leave her guests to go downstairs, discard the plastic containers and place the food into her own pots. This would help her hide the fact that the food was not home-made.

However, often times, an untimely doorbell or a phone call from the taxi driver asking for directions would give her away and cause embarrassment. Later, Leila tried serving simpler dishes that required less preparation. But as time passed, she invited people to her house less often. It was better not to have any guests than to fail in acting as a hospitable host.

A wall, built

Every Mehr apartment near Esfahan’s Dowlatabad accommodates 16 dwelling units in 4 stories built on pilotis (stilts raising the first floor above a parking garage). To meet regulations for the minimum number of parking spaces, the ground floor has a fully open layout. Its perimeter is cordoned off, but the walls are thin, half the usual height and combined with a fence. This arrangement allowed saving costs on construction materials. With time, the children of a neighbouring building realised that this arrangement also allowed them to see one another when playing outside. Leila’s daughter, Mahdieh, explained to me that this was exceptionally useful on summer afternoons: Once one or two children braved the heat for some bicycle runs, it would take mere seconds for tens more to show up and soon the whole crew would be together.

In spring of 2019, some of the parents in Mahdieh’s building organised a meeting to discuss an emerging concern about the carpark walls. A few of them had second and third grade daughters about to turn 9 years old. To turn 9 for girls is to turn bāligh (بالغ – mature), mature, and to reach the age where you must take responsibility for Islamic gender roles and dress codes. This moment is also a turning point for the parents, who become aware of the possibility of an unwanted gaze on the bāligh body of their daughters.

To become the parent of a bāligh girl is to take on the patriarchal responsibility of protecting her. Mahdieh and some of her friends had not been so keen on wearing the Islamic dress code, the scarf and long sleeve top, when riding their bikes on the warm afternoons. Parents had also not been keen on forcing them to do so, but they still felt a responsibility. As a result, these parents chipped in to get thick plastic sheets and bind them to the white steel bars around the carpark. Residents of nearby apartment buildings used a similar technique to block potential gazes too. This move, Mahdieh muttered, had made her group bicycle rides difficult to organise.

What then is to be made of these stories? What is to be made of the story of a wall that was demolished and a wall that was built?

The demolishing of the partition wall between the kitchen and living room is tied to the story of a working-class woman who fights to become motoahhel (married) and struggles to find her role after this turning point. Similarly, the building of the partition wall between two neighbouring carparks is tied to the story of a third grader who turns bāligh (بالغ – mature) and struggles to maintain her choice of outfits and her relationships with neighborhood friends.

These walls are also tied to stories of compassionate state leaders who fight to protect the nation against Western imperialism, and of compassionate working-class parents who fight to protect the bodies of their daughters. Demolished or built, each of these walls hold the stories of individual women who enter into ‘bargaining’ with multi-scalar structures of familial patriarchy and state patronage that traverse the intimate space of the domestic units to that of national territory. And it is in these bargains, in these local and incisive pushes and pulls, that a Mehr woman becomes.

But there can exist alternative parables of becoming. There can be parables that go beyond the individuated bargains with monstrous structures of compassion, patronage and patriarchy: parables that upset these archaic hierarchies and inspire new models of relating and making kin. There can be becomings that are plural: becomings whose domain expands beyond the immediate partition walls separating kitchens from the living rooms, playgrounds from the street, and working-class townships from the larger cities. Of the original target of four million dwellings set by Mehr, 2.3 million materialised. Spread throughout Iran’s national territory, from the Caspian Sea shores in the north to the Persian Gulf in the south, and from the borders with Iraq in the west to those with Afghanistan in the east, Mehr represents an extra-territorial archipelago shared between an approximate 6.9 million working-class Iranians. Mehr is a vast territory, and its women are yet to write their parable of becoming.

1 comment