The following was written by Aria Safar, the founder of Farr Collective. He works at the intersection of technology, graphic design, and community gathering.

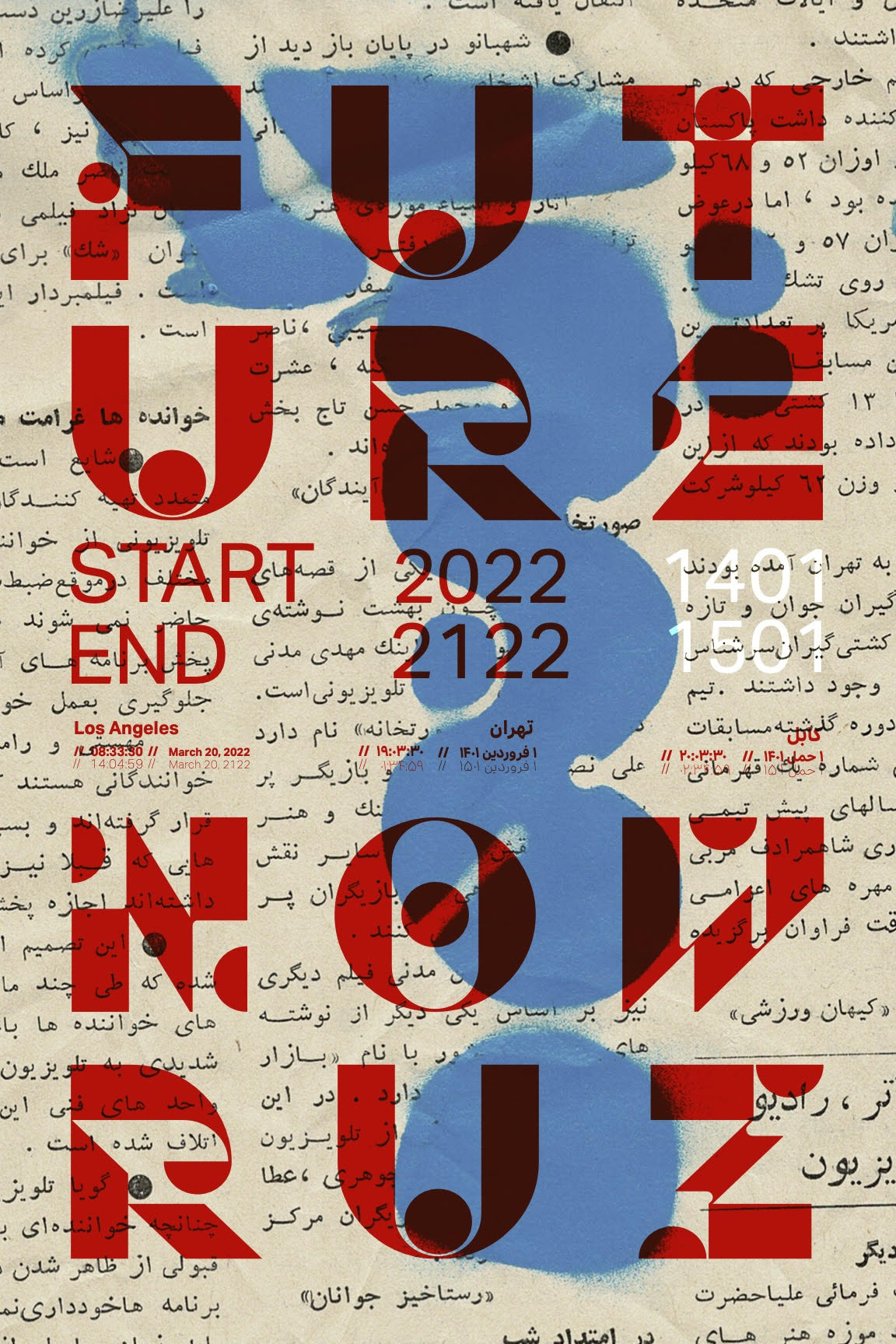

The following is part of a project called Future Nowruz that seeks to imagine more hopeful futures for the next 50 years. We are looking for stories and images; please find the submission form here.

***

The arrival of Nowruz (Persian New Year) this year marked the beginning of the year 1401 in the Solar Hijri calendar. The dawning of this new century conjures up images of a new future. It offers us a chance to imagine what is to come. How will we, as Nowruzis, the people from across the Persianate world who celebrate Nowruz, celebrate Persian new year in the near future? Will we put on virtual reality headsets to experience saal-tahvil (the moment of equinox) in front of a constructed haft-seen or haft-mewa with our relatives who may be across the world? Or will we finally be reunited in the same physical space, in an Iran, Afghanistan, Central Asia, or California in a border-free world?

The sudden changes that COVID-19 brought made dramatic shifts feel more possible than ever. Lockdowns saw people’s everyday lives shift suddenly–from government-provided universal basic income, to the end of in-person office work, to animals roaming in spaces previously occupied by humans and vehicles. On the other hand, it made it to difficult to predict what would happen next. The trauma of a life-shaking pandemic, the smartphone-delivered instant updates of war, new COVID-19 variants, and bleak climate change reports force us to care for and protect ourselves in the present rather than have the peace of mind, creative space and hopefulness to imagine a better future.

Recent years have seen suffering visited upon our region on an almost unimaginable scale. Only last summer, we watched Afghanistan’s Kabul fall to the Taliban, a reminder of the oppressive and dictatorial regimes that hold sway in so many nearby capital cities. Decades of war and sanctions, and now climate change-induced drought, have devastated people’s livelihoods across the region. The specter of war, death, and starvation today stalks so many of the cities where we mark Nowruz.

A common reaction to bleakness and trauma in our past and present is to look backwards. My Iranian parents, like many others, found comfort in the nostalgia of better times. Even younger generations’ imagination is fed by the omnipresence of nostalgia in the media, art, and visuals. Referencing the past seems like the only way to experience something better than the present.

Too much of this nostalgia, however, blocks us from imagining a better future. This new century gives us an opportunity to look to the future with a sense of imagination; to hope for something better, rather than focusing on the nostalgia and mythology of the past. The future for Nowruzis should not be built by reverting to imperial mythologies. Nor should better futures simply replicate other nations’ political or economic models. A copy-paste of liberal democracy and Western capitalism is not the answer. Futurism, that is imagining a potential reality built with the cultural and historical context of Nowruzis in mind, gives us the opportunity to build towards something better than our present.

In this essay, I hope to outline how speculative fiction can be a source of inspiration for conceiving of a future world, while building upon Nowruzis’ different historical and cultural contexts. Storytelling can be the bridge towards a more optimistic outlook for Nowruzis that can counterbalance looking to a better past. I end with an invitation for you to join me in building a future narrative for Persianate communities by submitting a short story or illustration to help imagine how we’ll celebrate Nowruz in the next 20-50 years.

Science fiction has for decades played an important role in helping people imagine the kinds of technologies and events that could shape the future. Western popular culture is full of examples. In 1962, the Jetsons depicted flying cars (not yet real) and video calls (now a part of everyday life). In 1973, Motorola announced the first cell phone, inspired by Star Trek and its cast of space-faring humans in the 2260s. General Motors’ Futurama Exhibition in the 1939 World’s Fair, with an installation visualizing the United States 20 years later, shaped the last century’s American dream (and expectation) of a suburban house with electric appliances and a car for every family.

Nowruzis can learn a lot from how science fiction can construct future narratives, but shouldn’t adopt the West’s science fiction exports wholesale. No story is universal. It reflects the specific perspectives of its creators, often dominated by Western white males. As speculative fiction author NK Jemisin writes of growing up watching Star Trek, “Star Trek takes place 500 years from now, supposedly long after humanity has transcended racism, sexism, etc. But there’s still only one black person on the crew, and she’s the receptionist.” The 2021 movie version of Dune centers white protagonists and continues Hollywood’s tradition of othering Muslim characters as the enemy.

For this reason, Nowruzis need to bring their experiences, history, and culture to create, and be the protagonists of their own narratives. It’s time for us to start telling our own stories and move beyond nostalgia to imagine our futures. In doing so, we could ask questions like, what timelines of events can we dream up for the next 20, 40, or 100 years?

What political, cultural, economic, or environmental events will shape how Nowruzis celebrate the new year in 1431/2052 Toronto, or 1441/2062 Samarqand, or 1461/2082 Herat? What will be the second-order effects of supersonic travel between Tehran and Los Angeles, where passports and visa regimes are only a faint memory? How may Nowruzis develop an alternative to travel where pre-planning and speed are not the goal, but instead relishing the journey in community? Imagine solar-powered electric buses taking travelers from Yerevan to Baku and onward to Tashkent with stops at caravansaries in between vehicle charges. How will language, aesthetics, and identities shift as Nowruzis experience borderless travel?

We can go beyond the limits of science fiction to the wider umbrella of “speculative fiction” to find inspiration. This can include reworking history to imagine alternative narratives that inspire us for the worlds we dream up. Black Panther is an example of a recent work of pop culture that offers an idea of different futures by rewriting the past. The comic book and blockbuster film helps us ask questions like, “what would the Global South have looked like without European colonialism?” The world of Wakanda shows us a blueprint of that in a fictional space on the African continent, with the added complexity of the richness of a fictional resource, vibranium. We may not be able to reverse time, but imagining alternative futures can remind us that the present we inhabit is not inevitable; it’s just one way things could have turned out.

Rewriting the past to imagine the future also means discarding the narratives that progress is unidirectional. Let’s not imagine the whole world as doomed to slowly lose its diversity and become a singular monoculture. What if we imagined our region not as moving toward a Persian monoculture but as one where the beauty, richness, and different characteristics of the region’s diverse communities like Qashqais, Bakhtiaris, and Pamiris are retained and celebrated? Africanfuturist Nnedi Okorafor explores the continuity of indigenous people against the tide of universalism and globalization. In her Binti Trilogy, the Himba people, a small indigenous community of 50,000 in present day Namibia and Angola, retain their identity and draw on indigenous knowledge disregarded by colonizers to become communications technology experts and forge bonds with non-human species in space.

For too long, the identity of many in our region has been defined by a pride in ancient imperialisms, in wars of the past that offer less of a roadmap toward the future and more of a longing for renewed domination. Many Iranians like myself, for example, grew up with the mythology of the 2500 year-old Persian Empire; the grandeur of Cyrus the Great and this massive, diverse empire built by the Achaemenids; a history that the Pahlavi Dynasty more recently co-opted. This mythology was given to us to hold our heads high; to differentiate us from our neighbors; to make imperialism desirable so long as it’s under our control. Without critically looking at these myths and nostalgia, we hold ourselves back from building better alternatives. But discarding the imperialisms of the past does not mean avoiding history completely.

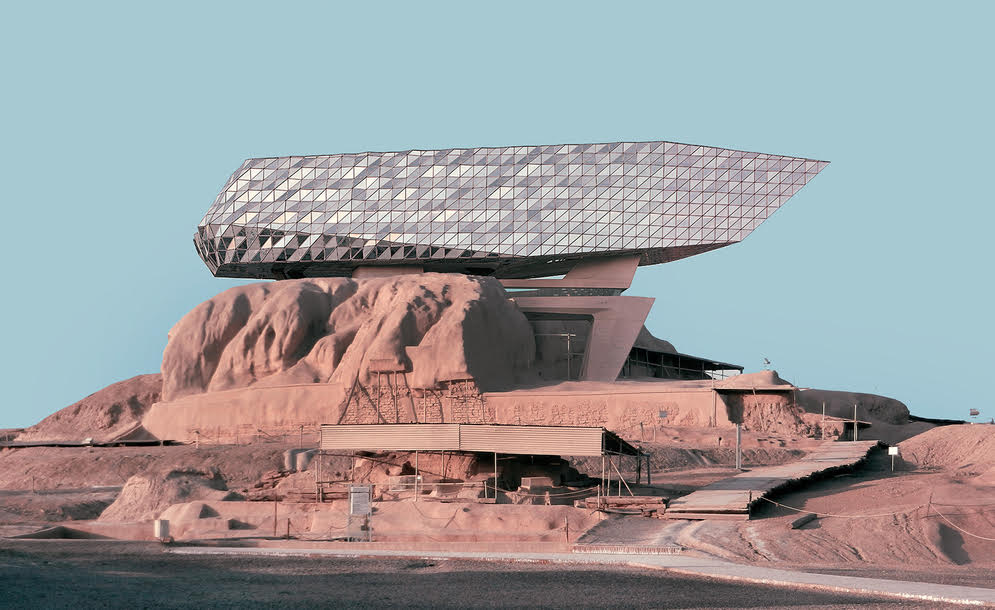

The cultural richness of our region provides far more inspiration for dignity, beauty, and sustainability than the armies of its defunct empires. Imagine instead the ancient history of Persian gardens, spaces that mimicked the human image of paradise. In a post-pandemic world, how might Persian gardens be reborn as the future centers of community, public gathering, and discourse? Or how could a Persianate focus on balance, in the figure of Ahura Mazda and the celebration of vernal equinox, create future approaches to ecological balance? How could our understanding of “hot” and “cold” foods help us imagine more balanced approaches to our living habits and our bodies? Or beyond that, to human society’s relationship of giving and taking from the Earth.

If we draw on more contemporary experiences, we learn about the different historical contexts that inform Nowruzis’ perspectives on the present and future. While some recent Iranian science fiction has begun to explore themes of sanction busting, bigger questions arise, like how have continued international sanctions following the Iranian Revolution and the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan created opportunity for alternative economic structures to global capitalism? How might trust networks that evade sanctions to deliver gifts, DVDs, and essential medicine between friends and relatives to and from the West and Iran and Afghanistan, be the foundation for community mutual aid and alternative systems of credit? What can we learn from a society that has become so skeptical of strangers, but willing to give so much to protect the health and safety of its smaller circles?

All the creativity needed to survive our present realities, and all the worlds built to evade oppressive institutions, give me hope. Our community has always found ways around challenges. Every year, we celebrate life, rebirth, and renewal during Nowruz. As we begin this new century, I come filled with hope that we can imagine, and therefore build better futures by and for our community. So let us work together to imagine these futures. Let us write, draw, and create what we imagine the world could look like one day in the future. What will Nowruz look like in 1425? Or 1450? Or 1500?

If you too are inspired by this vision, then join me.

On behalf of Ajam, we invite you to submit your pitch for short stories (approx. 1000 words), illustrations, graphic design, or other media in any language that will help us imagine how we’ll celebrate Nowruz in the next 20-50 years.

See this link for more information on the pitch, and to submit your pitch by Tirgan (summer solstice) on June 20, 2022. Selected works will be published on Ajam as part of a collection of work, and given an honorarium.