This article is the second installment in a three-part series on oil, nostalgia, and the southwestern Iranian city of Abadan.The first part in the series can be found here and the third part can be found here.

The series is authored by Rasmus Christian Elling, an assistant professor at the University of Copenhagen where he teaches the sociology and modern history of Iran as well as urban theory. He has recently published a book on minorities, ethnicity and nationalism in Iran after Khomeini, and is now working on the history of Abadan. This series was originally published in Danish.

You can support Elling’s Internet campaign to fund more research and publications on Abadan here.

Part Two

Abadan is special. Or at least, it used to be special.

Its urban and social fabric stands out from all other Iranians cities. Its inhabitants are unmistakably Abadani. How is that? If oil can create a city, can it also shape an identity?

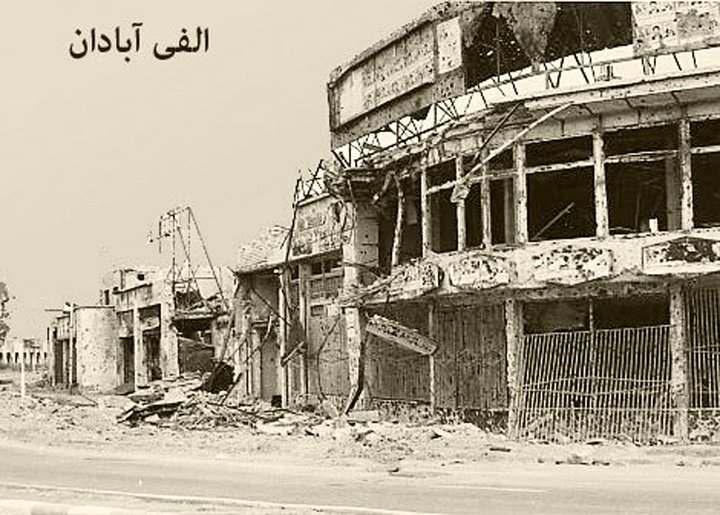

Abadan’s past status as an international city is central to stories of what it means to be an Abadani. Despite the injustice and inequality of the past, and despite Abadan’s rapid decline during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, Abadanis are still proud of their city and their history. That history is so deeply mired in the story of oil that it is impossible to tell the one without the other.

With the phenomenal growth of the oil industry across Khuzestan Province from the 1910s, the Company realized that a whole new city was needed in Abadan.

Next to the absence of infrastructure, the biggest concern facing the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (later renamed Anglo-Iranian and today BP) was the supposed lack of skills and ‘discipline’ in the local population. Although locals were hired for basic manual tasks, the Company preferred to import labor from India, Mesopotamia, Palestine, Burma and even China. Eventually and reluctantly, the Company would employ Iranians. Soon, migrants from all over Iran descended on Abadan in search of work.

The British and their white Western colleagues stood at the top of the labor hierarchy that emerged. For the technical, administrative and menial work, they mostly employed those they deemed trustworthy: the Indians, Christian Armenians and Assyrians, and Jews. Muslim Iranians were employed in the lowest rung of the hierarchy, toiling in danger and living in misery.

Since many Company officers had a background in British India, they brought with them colonialist, racist ideas about managing a multi-ethnic, overcrowded society — ideas that materialized in urban planning.

In the Braim neighborhood, on one end of Abadan Island, where breezes made tropical life bearable, the British nurtured their culture in bungalows, cricket clubs, gardens, and at tea parties.

Here, they were segregated, until oil nationalization, from the non-white population by the refinery, which functioned as a huge, metallic barrier on the middle of the island.

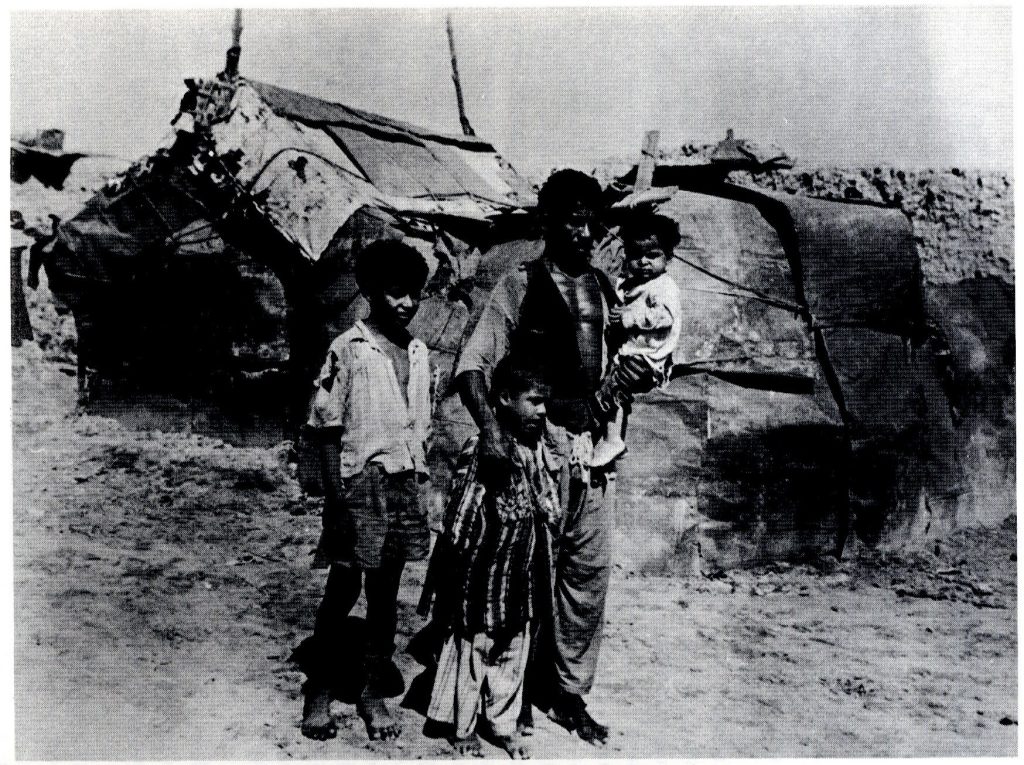

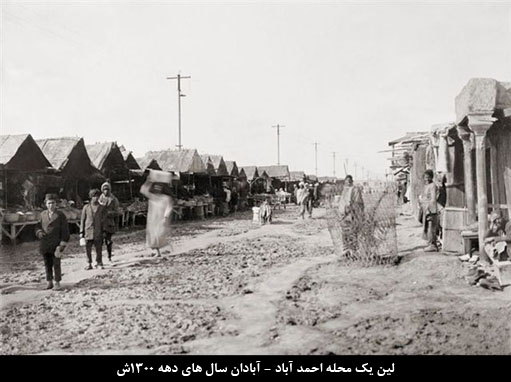

On the other end of the island was ‘The Native Town’: sprawling slums with crime, diseases and disorder, real and imagined, which the British feared could spill over at any time.

On the other end of the island was ‘The Native Town’: sprawling slums with crime, diseases and disorder, real and imagined, which the British feared could spill over at any time.

Relations were tense between immigrants and the local Arab-Iranians who were watching as their palm groves gave way to an industrial city. But the industry also generated new dynamics of contention. As early as 1918, Indian migrant workers protested their maltreatment by the Company, and when they went on strike to demand higher wages, they signaled the birth of an oil labor movement in Iran.

The British responded with heavy-handed repression, control and surveillance.

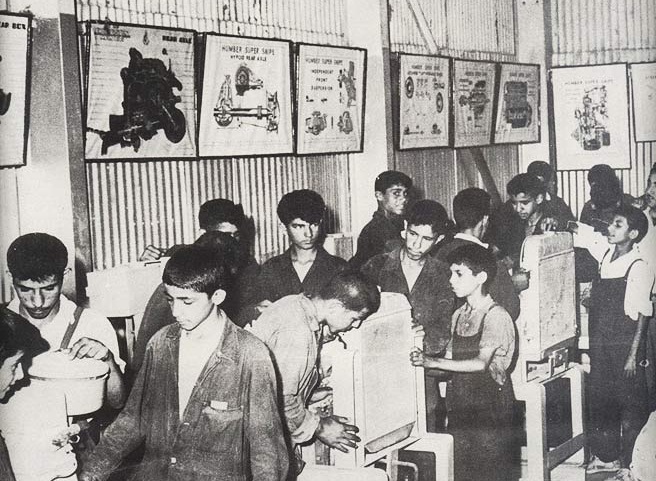

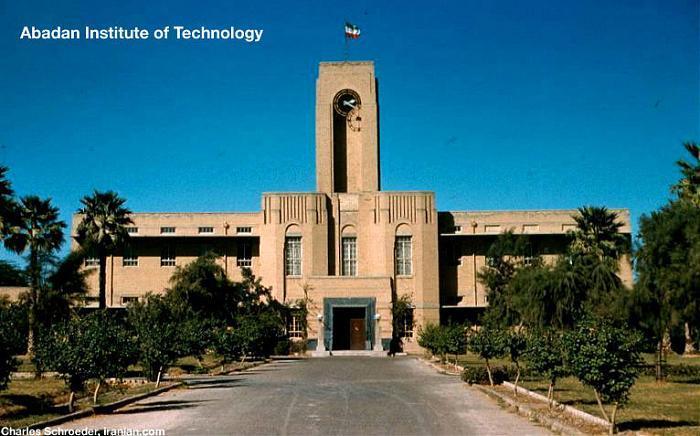

To offset rising discontent, the Company imported pre-fabricated barracks to house laborers. From the mid-1920s, it began to install sewerage and electricity while extending roads, public transport and health services. In time, the Company built schools, social clubs, cinemas and a university, and in the 1940s, it established whole new neighborhoods in Bawarda and Bahmanshir.

To offset rising discontent, the Company imported pre-fabricated barracks to house laborers. From the mid-1920s, it began to install sewerage and electricity while extending roads, public transport and health services. In time, the Company built schools, social clubs, cinemas and a university, and in the 1940s, it established whole new neighborhoods in Bawarda and Bahmanshir.

In exchange for taking responsibility for urban development, the Company allowed itself to run Khuzestan as a de facto state within the Iranian state, and with Abadan as its capital.

Abadan’s population grew from 40,000 in the early 1920s to 200,000 in the 1940s. From the 1930s, some Iranians were able to move into the new middle class. Oil had brought about modern welfare and material progress unheard of in Iran at that stage. But it had also brought into being a segregated class society, modelled on the colonial-capitalist logic of a British corporation.

On such a background, it would be no surprise if Abadanis consider the British past a dark chapter of the city’s history. And yet, the pre-nationalization past is often invoked with a sense of loss.

Visitors to Abadan are constantly reminded that the city was once the capital of modernity in Iran: a cosmopolitan beacon for the Middle East and a prominent point on the world map.

It is on this global scale that Abadanis tend to quantify the city’s past splendor and contrast it with its present sorry state.

Abadanis are proud, and sometimes the pride turns into ironic exaggeration or lâf– the stuff of many jokes in Iran, but also a self-conscious form of expression in Abadani popular culture. Let me give an example.

An Abadani who — just as all of his fellow citizens, it seems — is a huge fan of football was not really interested in my questions about the social structure of Abadan in the past. He was rather interested in why my country’s football team had never visited his city to play the local outfit, San’atNaft(‘The Oil Industry’). He resorted to lâf: “Before the Danes could even set foot in Abadan, we would have beaten them 3-0! The only team who would stand a chance against us is Brazil!”

Curiously, Abadanis tend to associate their city with Brazil. A local researcher I met during my first visit proposes that the similarities in the tropical climate, the palm trees and the warm-blooded mentality may have caused this association. It may also be the simple fact that the colors of FC San’at-e Naft are the same as that of the Brazilian team, or that Abadanis allegedly play “samba style” football. A popular saying is Âbâdân berâzilete!, or ‘Abadan is your Brazil!’

This imagined link with Brazil shows how the city sees itself in a global rather than merely Iranian context. And the international past lingers on in everyday life.

This imagined link with Brazil shows how the city sees itself in a global rather than merely Iranian context. And the international past lingers on in everyday life.

There are numerous English words in Abadani dialect, as well as loanwords from Hindi and Punjabi. Streets that were renamed with Islamic and Iranian names after the revolution are still called lanes – including Sikh Lane (actually, Sikh Line), once inhabited by Indians.

One of Abadan’s more intriguing buildings is the Masjed-e Ranguni-hâ (‘The Burmese Mosque’), built with inspiration from Indian temple architecture but undergirded by discarded oil pipes. The Anglo-Indian past is also reflected in the food culture, which differs from Persian cuisine with spicy curries, chapatti bread, pakora snacks and chutneys.

The connection to Britain, although formally broken with the oil nationalization in 1951, is still tangible.

In the local vernacular, Abadan was dubbed ‘Second London’ (landan-e sâni), and one of its famous squares (Alfi) was known as ‘Piccadilly Circus.’

I am told again and again that there used to be direct daily flights to England; that London Times was delivered every morning as it hit the streets of the metropolis; that films premiered in Abadan simultaneously with British cinemas; that many buildings were constructed with the “London red brick”; and that the local university cooperated with Birmingham.

I am told again and again that there used to be direct daily flights to England; that London Times was delivered every morning as it hit the streets of the metropolis; that films premiered in Abadan simultaneously with British cinemas; that many buildings were constructed with the “London red brick”; and that the local university cooperated with Birmingham.

Most Indians, Jews and Christians have left the city, but they are nonetheless eagerly reminisced by Abadanis. There are only two Indian restaurants left in Abadan, but they remain the most popular. The airport seems dilapidated and distinctly provincial. They day I visit the old university, it is completely deserted. There is no London Times to be found in the kiosks. And yet Abadan insists on its global identity.

Through pipelines, shipping lines and airlines, oil connected Abadan to the rest of the world spatially; temporally, it synchronized the city with the modern West.

Today, when most have forgotten Abadan, and the city has slipped into the periphery, its past connection to the world is still a source of local pride.

From cosmopolitanism to provincialism

A local researcher compares Abadani identity with the ma’jun smoothie, a blend of banana, honey, coconut, pistachio and dates.

Abadanis, he says, are the mixed product of the city: “I lived in an alley, where there was a Christian Lebanese Arab, an Indian family, a family from Bushehr, one from Tabriz and one from Dezful. We lived side by side without any problems,” he says. Rather than segregation and discrimination, Abadanis remember a strong sense of neighborly friendship, solidarity and harmony.“There was a church next to the mosque in our neighborhood,” another Abadani tells me.

When migrant workers came to Abadan from all over Iran, they tended to flock together in specific neighborhoods and mosques. There were Dashtestanis, Larestanis and Afro-Iranians from the south, Lors and Bakhtiyaris from the north, Behbahanis from the east; Armenian and Assyrian Christians, Jews, Bahais and Sabaeans; there were people from Shiraz and Esfahan, and those from further afield, Tehran, Tabriz, Bandar Abbas and Mashhad.

Yet the Company’s urban planning and mode of production brought people together in ways that differed from traditional life and generated new forms of socialization. Many migrants broke with old tribal bonds in their home regions when they moved to Abadan, and many married outside their ethnic group after they settled there. Together, these diverse peoples would craft a new culture that in many ways distilled and summed up all of Iran’s diversity in one city.

Within the spaces created by oil, Abadan gave rise to a new communal identity.

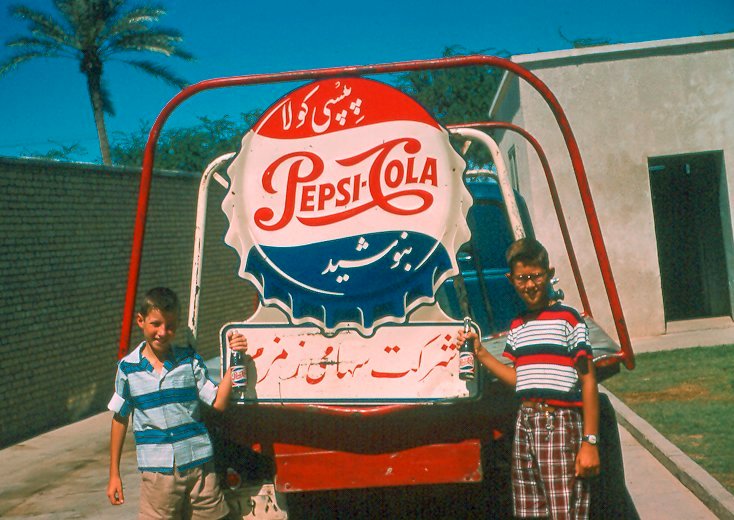

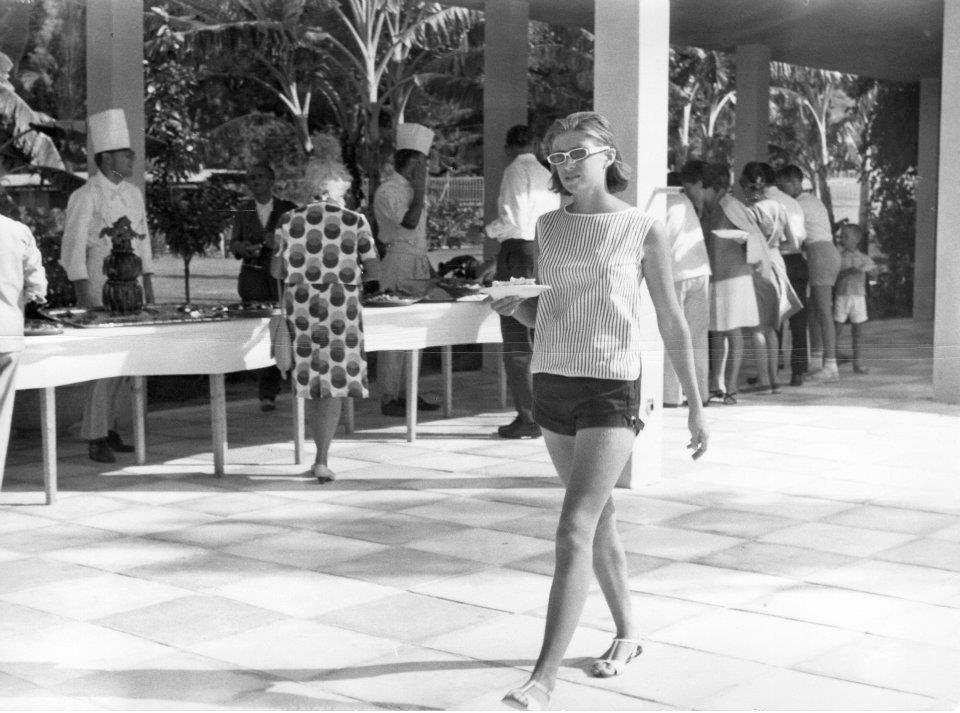

After the nationalization of oil, Abadan entered a new golden age from the mid-1950s. In this period, Abadan became the symbol of American-inspired materialism and consumerism, with the nuclear family and suburban life as the ideal. Many luxury items, foreign cars, washing machines and modern air-condition was imported for the first time into Iran via Abadan. Iranians and Westerners would mingle more freely, and a new middle class emerged.

The Company’s PR department disseminated the values that fitted the Shah’s vision of a secular, Westernized Iranian society.

The Company’s PR department disseminated the values that fitted the Shah’s vision of a secular, Westernized Iranian society.

This new society was attainable, Iranians were told,through the miracle of oil.And the Company, the oil wells, the pipelines, the refinery and the laborers were the catalysts of the miracle.

Iranian documentary about the oil city with a fascinating, sometimes eerie soundtrack.

With the new society came an obsession with looks and image. Abadanis were famous for their sense of fashion and for the distinct Abadani look.

The most important item was sunglasses, a trade mark of Abadan — to such an extent that there is a whole genre of jokes in Iran related to the Abadani love of Ray-Bans. But also Western clothing, Clarks’ shoes and beach sandals, American jeans and British shirts defined Abadani chic. “When we traveled up to Mashhad,” a banker tells me, “our friends would ask us to bring clothes.” An Abadani would spend much time and energy on grooming, and was a heavy user of perfumes and beauty products. The contrast between the traditional look and that of a refinery worker out for a Thursday evening stroll was sharp.

Clip from an Iranian documentary about the importance of Ray-Bans to Abadanis.

The nostalgic books praise Abadan’s many spaces for pastime recreation: the scout teams, sowing clubs and courses on hygiene and cooking; golf, wrestling and horse racing; swimming competitions, roller skating and backgammon on the cafés; not just Iran’s first cinemas but even 15 of them on the eve of the revolution; and of course the kind of after-work pursuits to which books published today can only allude through hints: the bars, cabarets and night clubs, opium dens, liquor stores and brothels.

Despite its history of social control, old Abadan is remembered today as a free-spirited, liberal and even hedonistic city. Many Iranians looked up to Abadan: they aspired to be employed by the Company, and the city was a popular destination for domestic tourism — “even though we don’t have any particular attractions,” the banker tells me.

Abadan’s attraction was its population; its pull on Iranians came from the ideas about the city that the magic powers of oil would conjure.

Today, Iranians still describe Abadanis as laidback, humorous, open and passionate people. The urban youth still appear less restrained and conformist than their counterparts in neighboring cities.

Abadani youth celebrating Nowruz, the Iranian New Year, in the streets.

And yet, many today complain that the disruptions of the war have prompted a growing conservatism. Instead of the cultural and political diversity that characterized the city before, tribalism and traditionalism have resurged. According to a local politician I interviewed, this has made Abadan a more provincial city. It has lost its cosmopolitanism.

It is as if the oil industry’s stagnation is seen as a root cause for cultural recession. The nostalgia pays homage to a time, when Abadan was bustling with culture and life, the envy of all Iran: an erstwhile trendsetter gone out of fashion.

An orderly time in space

What has been lost since the revolution and the war, many Abadanis say, is the order that characterized the city in the past: the discipline prompted by the oil industry and institutionalized in the society that the British created under the Company, and which continued under the Shah — but has since disappeared.

Abadan was an orderly city, and it is now out of order, the visitor is often told; not just because of the war, but due to the mismanagement of the city by both political elites and ordinary citizens. My interviewees complain that people cannot or will not respect the rules, that they show no respect for public space and that the city has lost its aesthetic identity. Citizens disregard regulations for how the houses once built by the Company are to be maintained, how gardens should be kept, facades cleaned and cars parked, and so on.

Abadan was an orderly city, and it is now out of order, the visitor is often told; not just because of the war, but due to the mismanagement of the city by both political elites and ordinary citizens. My interviewees complain that people cannot or will not respect the rules, that they show no respect for public space and that the city has lost its aesthetic identity. Citizens disregard regulations for how the houses once built by the Company are to be maintained, how gardens should be kept, facades cleaned and cars parked, and so on.

“The city has lost its historic face, and the mayor will not do anything — it is simply too difficult to change the mentality,” the local politician tells me.

Many memories and memoirs mention how the giant horns (feydus) of the refinery would signal the beginning and end of the work day. This created a sense of discipline that regulated urban life, and that my interviewees complain is missing today. The post services, pay checks, electricity and above all traffic is in shambles. “Back then, traffic would run smoothly, and you wouldn’t see garbage lying around in the streets,” an Abadani tells me — without specifying when ‘then’ was. “We had the best sewerage in the country,” a banker states. “Today, waste is seeping into buildings. The parks are unkempt, there are weeds growing everywhere and graffiti on the walls,” he sighs.

Today, more than 25 years after the war, there are still bullet holes in some buildings.

The loss of “order” is a recurrent theme in the nostalgic books, including IrajValizadeh’sAnglo and Bungalow in Abadan. Valizadeh contrasts the present state of the city with the order of the past through detailed descriptions of Company welfare projects.

He painstakingly describes how the British introduced schemes to alleviate hungerduring World War II. First, they would survey land outside the city in yards and feet; then subject the soil to desalination; and then allot it to local farmers under strict regulations for fertilizing and cultivating it. Then the Company conducted a census, divided Abadan into units of families, and allocated rationing coupons with which they could buy food stuff in new stores. In order to keep the calm during shopping hours, the British told Iranians to sit on the ground as they waited for their turn.

And thus, Valizadeh implies, Abadanis learned not only to respect the queue, but also to work together on solving collective problems in society, to use technology to cultivate the barren soil, and to distribute the yield through systematic measures. All of this was possible thanks to the social and industrial discipline brought about by oil.

Valizadeh is certainly not blind to the jarring inequality of British-run Abadan. And yet he shows a strong belief in the spirit that British entrepreneurship purportedly engendered in Abadan.

I often encounter such arguments in conversations with Abadanis: that everything was better during the British or before the revolution. Current local officials and managers are accused of inefficiency and cronyism. Abadan’s municipal authorities are paralyzed by internal conflicts and strapped for funding. A politician allegedly ran for local elections recently with the slogan “we don’t want progress – we want to return to twenty years before the revolution!” – a slogan that obviously runs counter to the official state narrative.

The waning magic of oil has left Abadani society to its own devices, and in the nostalgia for an orderly time with orderly spaces, Abadan hangs uneasily suspended in its own history.

…

When the Company established a system of technical and industrial routines that could be managed to meet one clear overriding objective —oil production— it also set in motion a chain of social processes that it could not control. Oil was the driving force of economic and urban development in Abadan, but it also became the lubricant for cultural development, shaping new forms of socialization and creating new imaginaries. Oil opened up new horizons and made Abadanis think of themselves and their city in a global context.

With the self-irony of lâf, Abadanis distance themselves from the exaggerated pride in a glorified past of order, style and status. But at the same time, a distinct Abadani identity persists wherever Abadanis have settled in the world. Perhaps we could visualize this identity, as the local researcher does, as a form of ma’jun. But another metaphor is oil. Just as crude undergoes processing and refining before it is shipped out as oil to become another thing another place, Abadani-ness, an unintended byproduct of the oil city’s development, became a culture and an imaginary in its own right.

Abadan is special.

In the last part of this essay, we will try to understand the trauma of war that holds Abadan in its grip; and how this relates to the experience of modernity in what was once Iran’s most modern city.

…

This essay is part of a reworked version of:

Elling, Rasmus Christian. 2014. ‘Oliebyen midt i en jazztid: Nostalgi, magi og det moderne i Abadan’, Tidsskriftet Kulturstudier, 2/24. Download here.

12 comments

I’ve been waiting for this!

I am Abadani and want thank you for the most amazing memories

Excellent job. I have been more than 20 years in abadan refinery – I have spent the two years of the first years of war responsible of abadan refinery and services (non-industrial) in Abadan. I am looking to find out the maximum number of foriener employees (English @ Hendish) in Abadan and in what window time. As well looking to figure out the number of housing there. I have the number of 12000 units.

Having spent time in Abadan 77 through 79 interested in this city, husband worked T the refinery and how the revolution and Iran Iraq war has Influenced the city and Iran. Wish to talk about the geography topography climate customs etc.

So much of this evokes my boyhood years spent in Abadan. Helps make better sense of my parents’ time there with my father working for the APC as an expatriate Indian engineer. provides so much context to piece together dimly remembered details. Great effort – thank you!

As a four year old I remember flying with my sister to Abadan via Tehran in 1958. We were met by my father, an oil company geologist and drove in a taxi across the desert the following day to MIS. It was July and the taxi was booked for 5am but arrived several hours later by which time the day was heating up. I couldn’t understand why my father made us drink a Pepsi Cola at a stopping place – this was a treat known only at Christmas – and no air con of course.

Thank you for your interesting and informative picture of Abadan. We still have books stamped Alfi’s Book Store, still revere our Gabbis, still remember the chappattis and (Nowruz) picnics in the mountains …

Oh most wonderful years of my life!!

Born and raised in Abadan, I did love it but after sudden loss of it I dream of it every time that I recalll those years!